No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

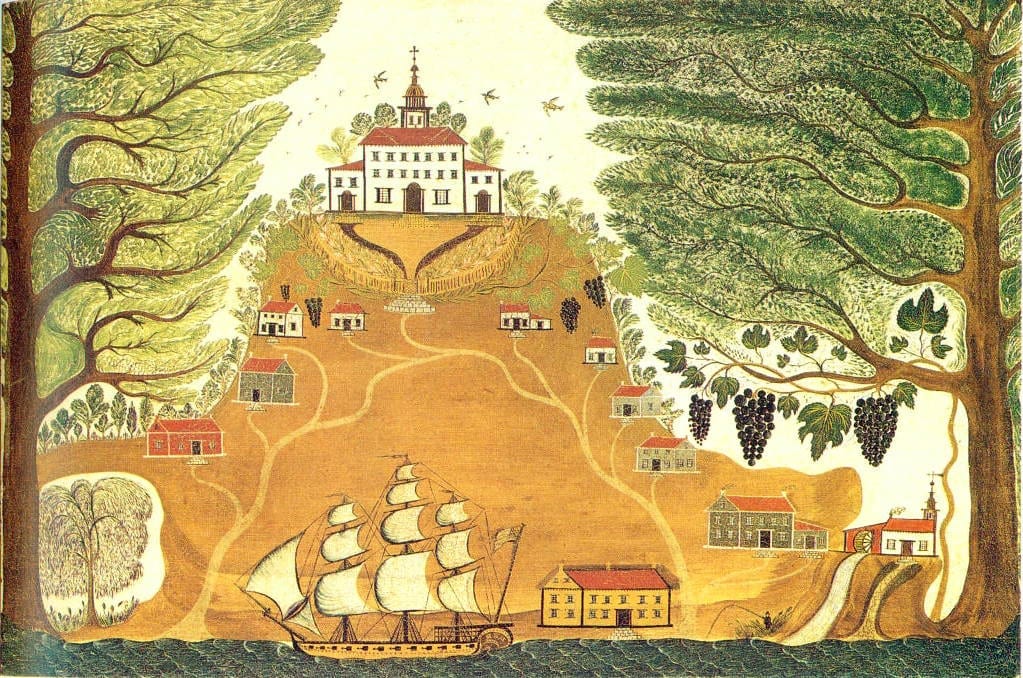

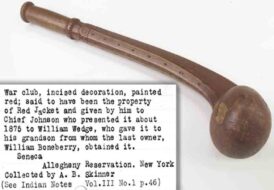

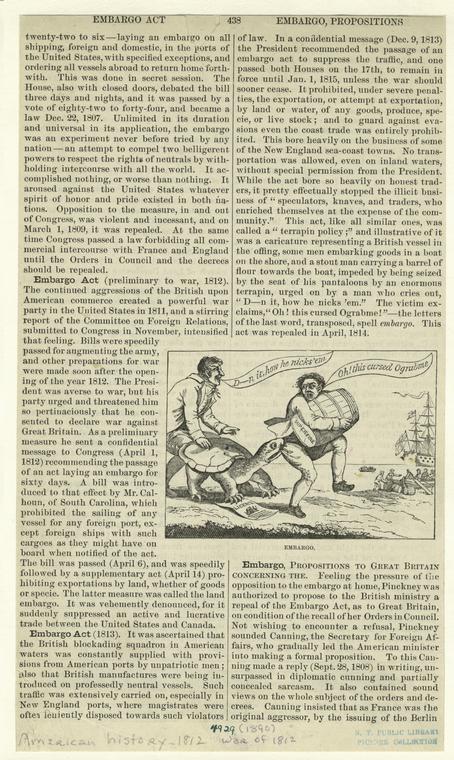

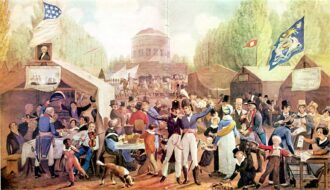

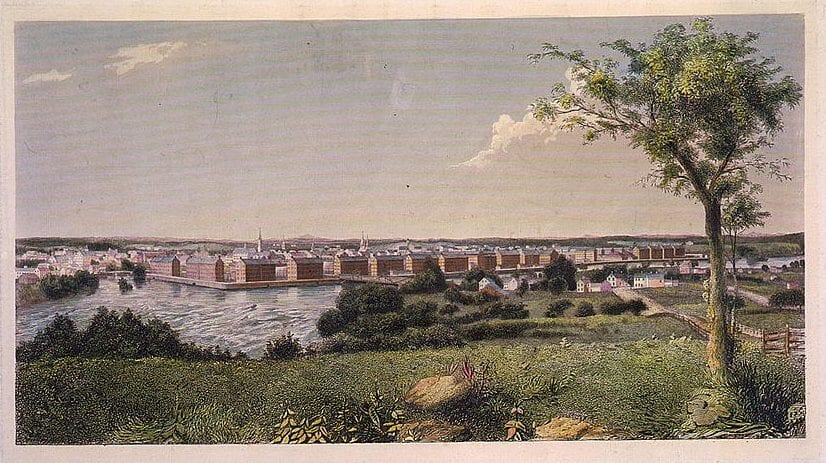

In 1791, the first Congress passed an excise tax on distilled alcohol, the first tax ever levied by the national government on a domestic manufacture. Farmers in the nation’s frontier counties (who commonly turned much of their grain crop into whiskey for easier transportation to eastern markets) bore the brunt of the tax and rapidly made their dissatisfaction with the policy known. Resistance was best organized in the four western counties of Pennsylvania, whose residents held a series of public meetings to draft petitions urging their representatives to repeal the law. At the same time, these meetings adopted resolutions advising individual non-compliance with the law, framing it as an unjust imposition upon the liberties of the people.

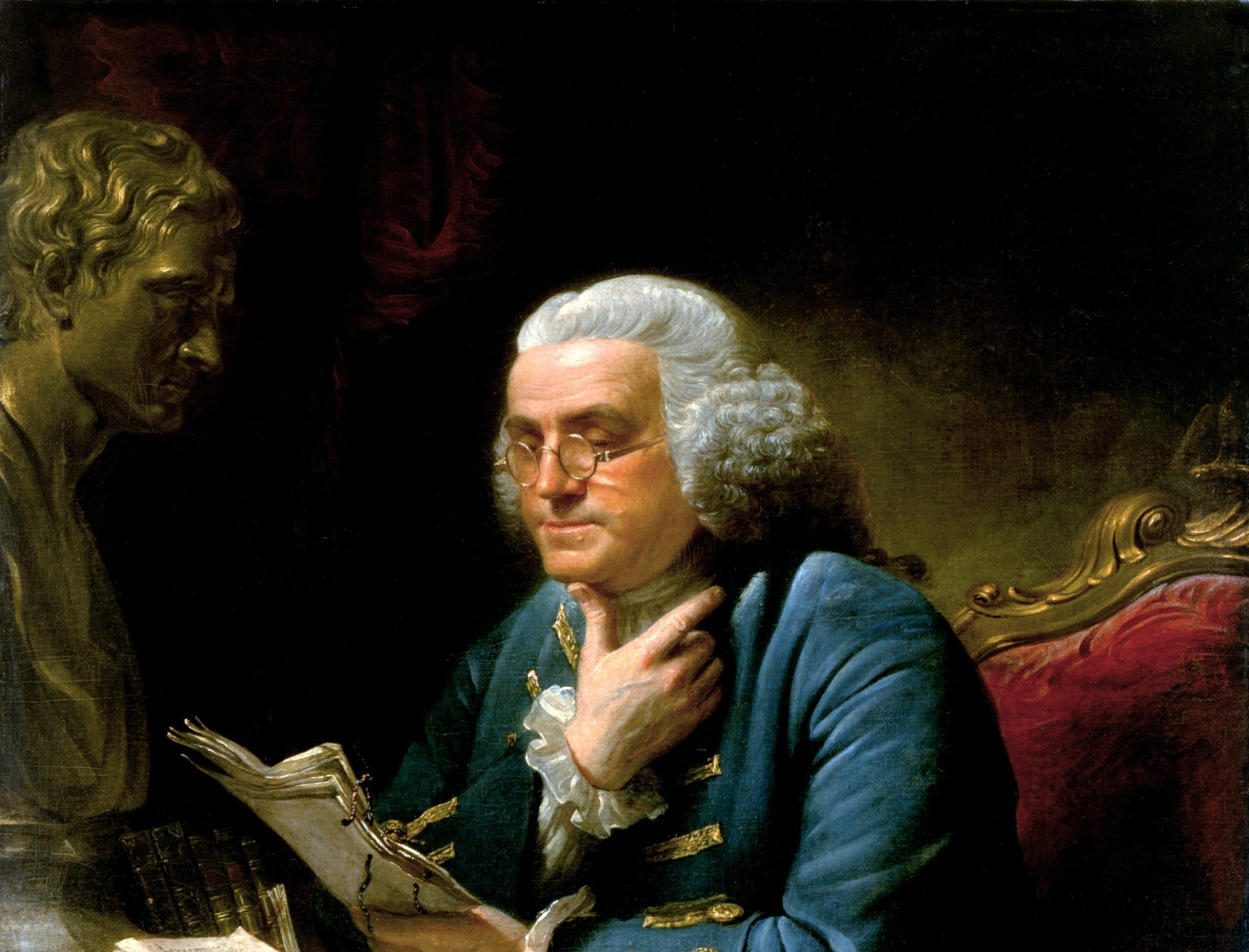

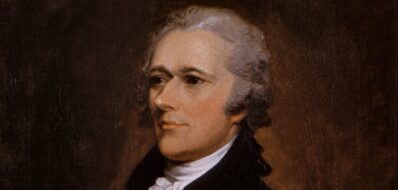

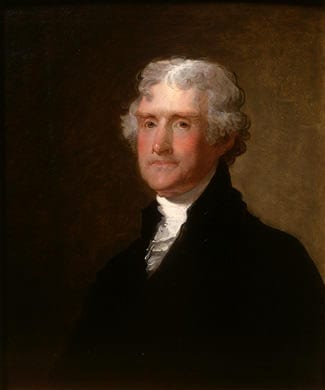

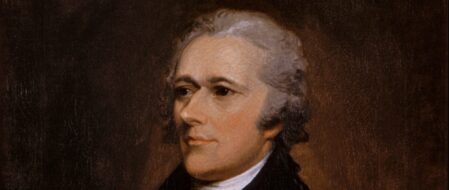

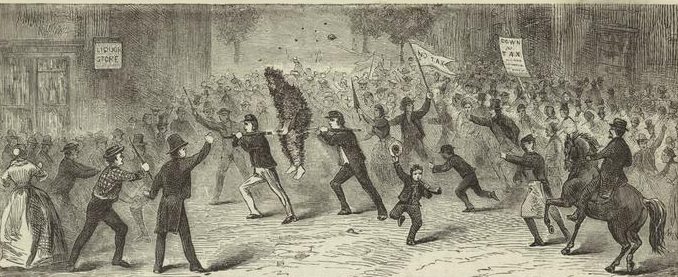

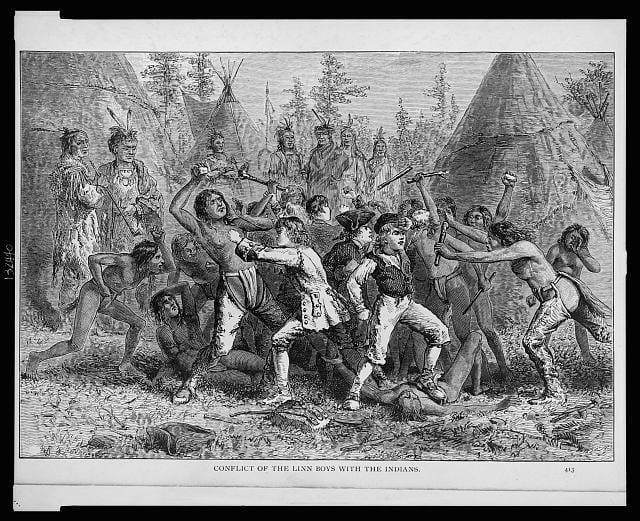

The conflict dragged on for several years, and when their initial efforts at peaceful non-compliance failed to secure the repeal of the excise, some western Pennsylvanians adopted tactics of violent resistance to the enforcement of the law. A number of excisemen were accosted in the line of duty, tarred and feathered and (in at least one instance) tied up outside overnight in an attempt to coerce them into renouncing their commissions. When accounts of the violence reached the national government in Philadelphia, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (whose department was ultimately responsible for the revenues collected by the excise) prepared a report for President George Washington.

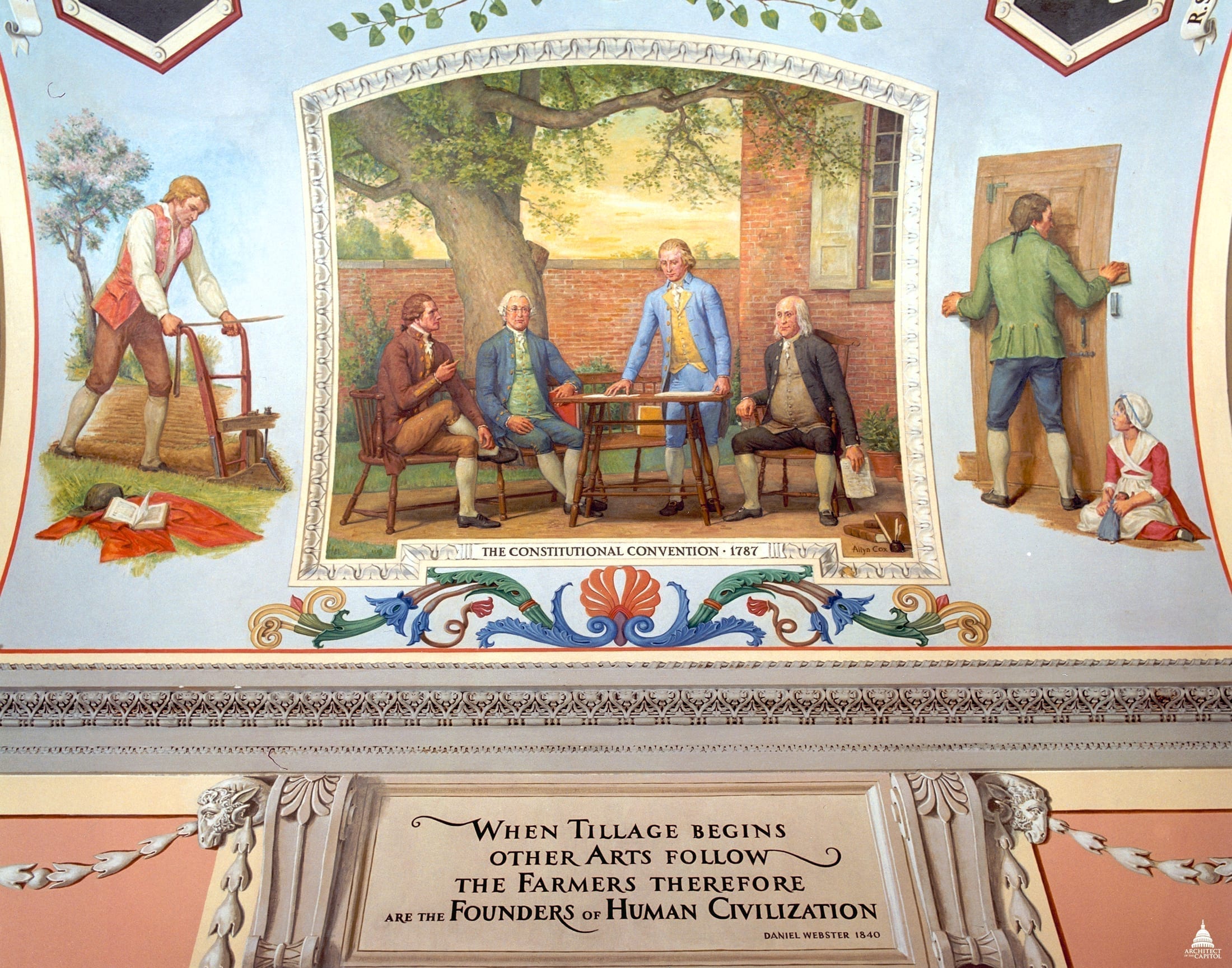

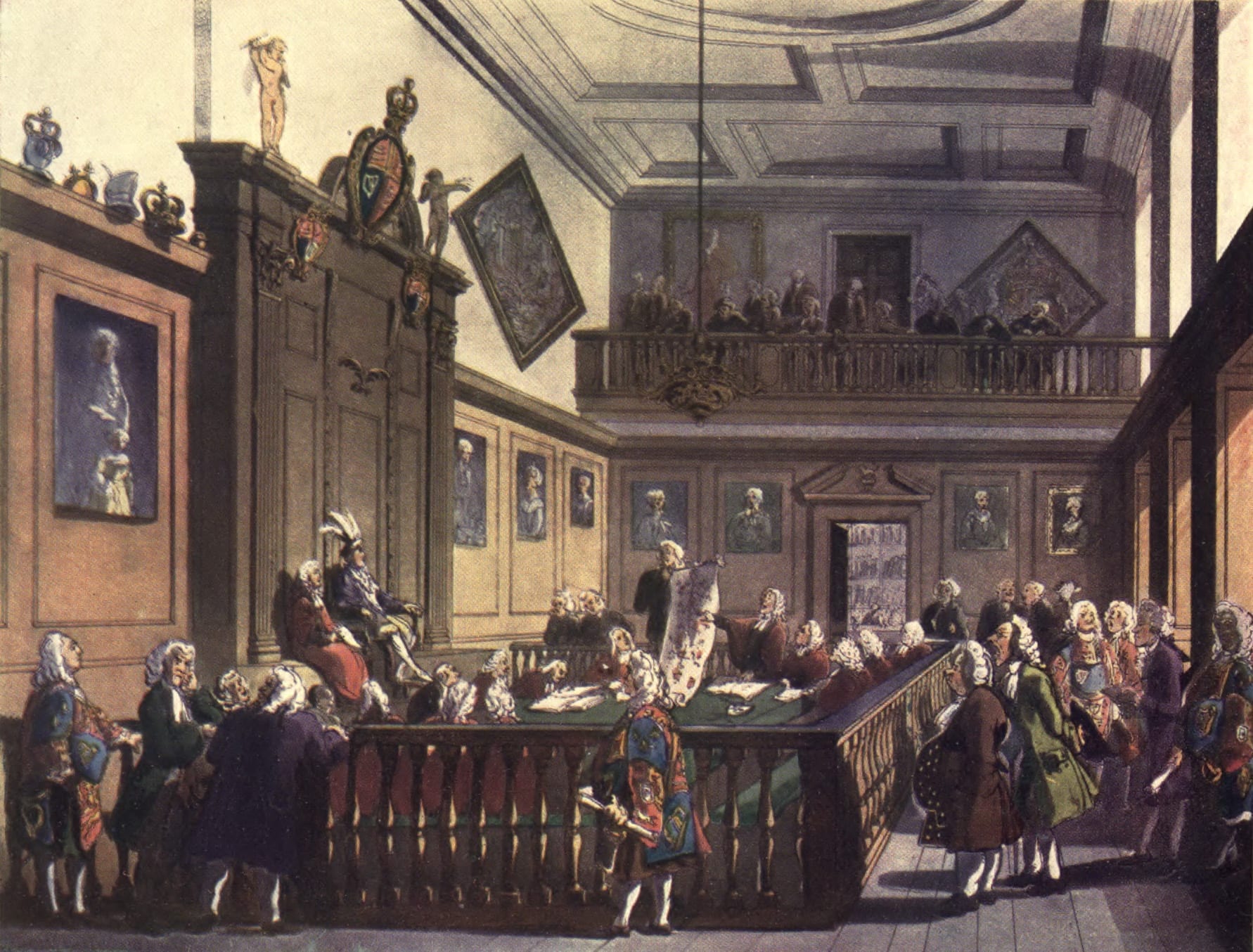

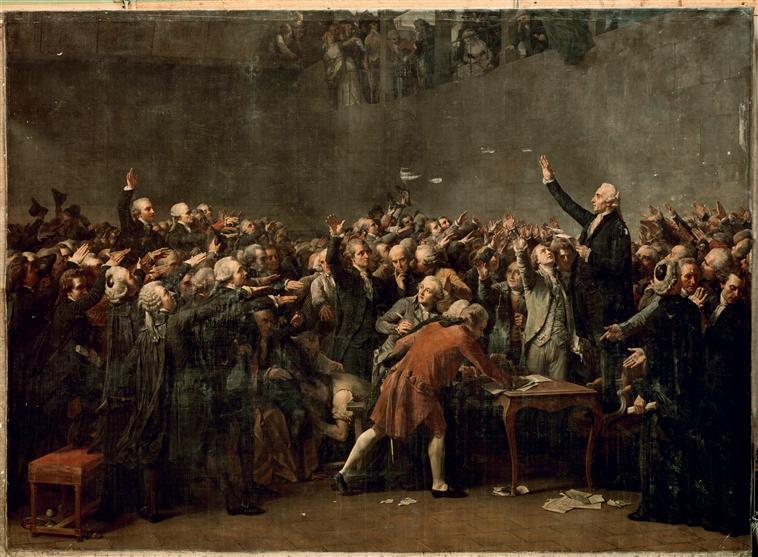

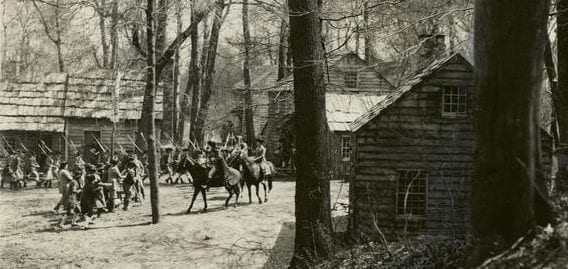

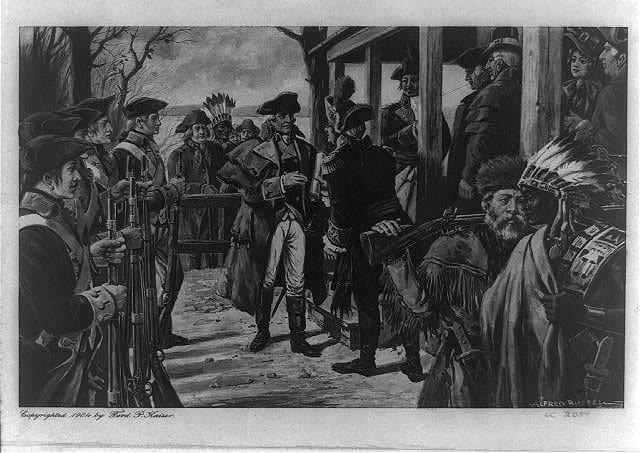

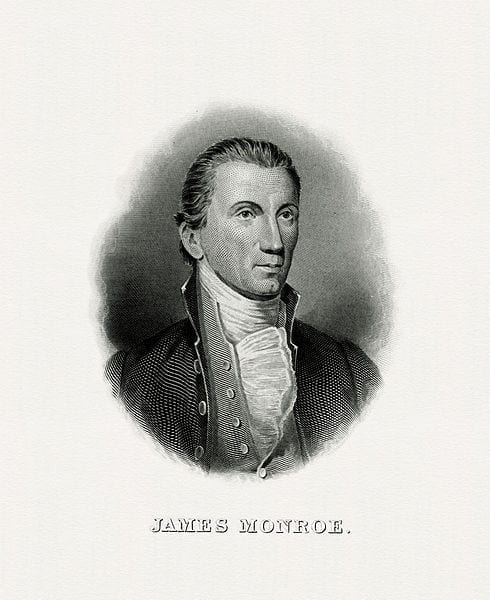

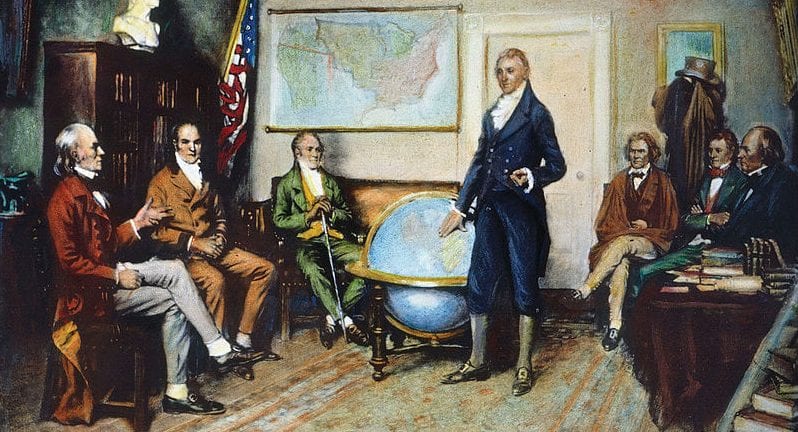

Hamilton’s report begins by describing the situation as a “disagreeable crisis” but ends by labeling the parties involved as insurgents, and their resistance as a domestic insurrection. He is frequently credited with convincing the president that matters would not be resolved apart from the use of military force, with the result that Washington issued a presidential proclamation to that effect. Meanwhile, Hamilton’s pseudonymous Tully essays were meant to turn public opinion against the rebellion and bolster public support for the president’s decision to send in the militia. (In actuality, Washington himself took command of the nearly 13,000 troops that were marched to the West in October 1794, the only time an American president has actually served as a combat commander while in office; see Frederick Kemmelmeyer’s painting of the event, Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland).

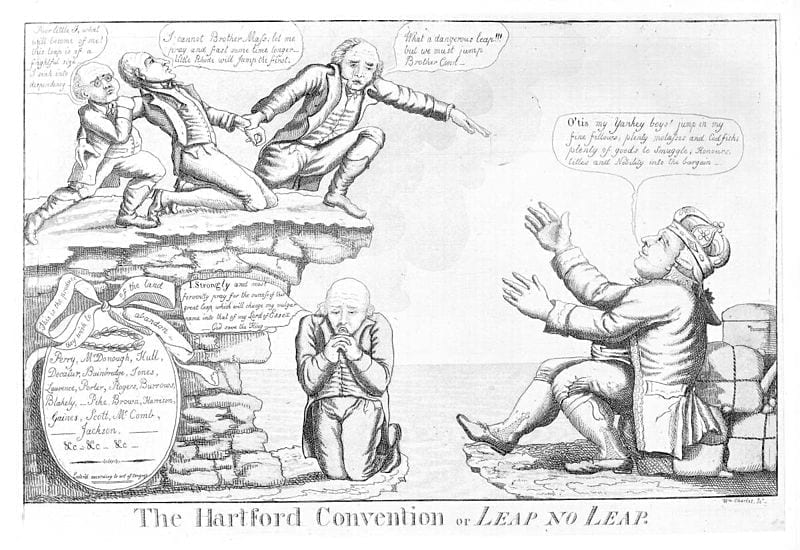

Hamilton’s essays and the marshaling of troops succeeded in quelling the rebellion without further violence. Yet the central question raised by the insurgency remained: to what extent and in what ways can citizens in a republic organize to resist laws they find unjust or immoral before becoming rebels or traitors? In the years following the incident, moderate opponents of the excise tax and other strongly national policies like it would offer opposing narratives of the insurrection in which they attempted to present the national government as oppressive.

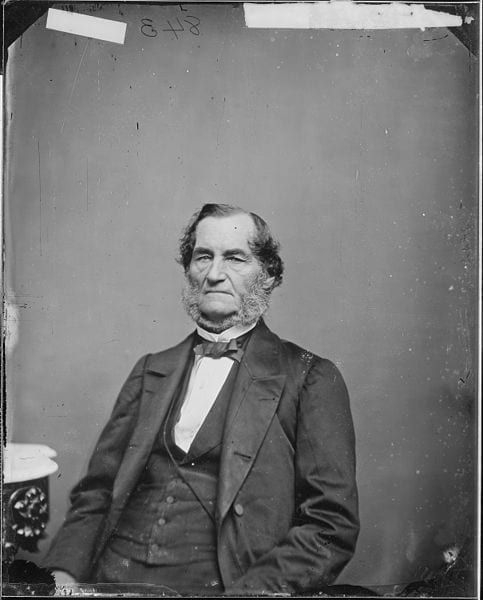

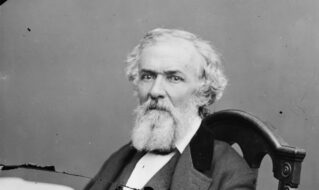

William Findley (a Republican from Western Pennsylvania who served as a long-time member of the House of Representatives), for example, downplays the violence of the rebels and instead focuses on the government’s attempt to restrict the freedoms of speech and association of individual citizens in his Defense of the Insurgents. Such interpretations were repeated by many others over the course of John Adams’s presidency and doubtlessly helped to bolster the rise of the Jeffersonian Republicans as a substantial opposition party within national politics.

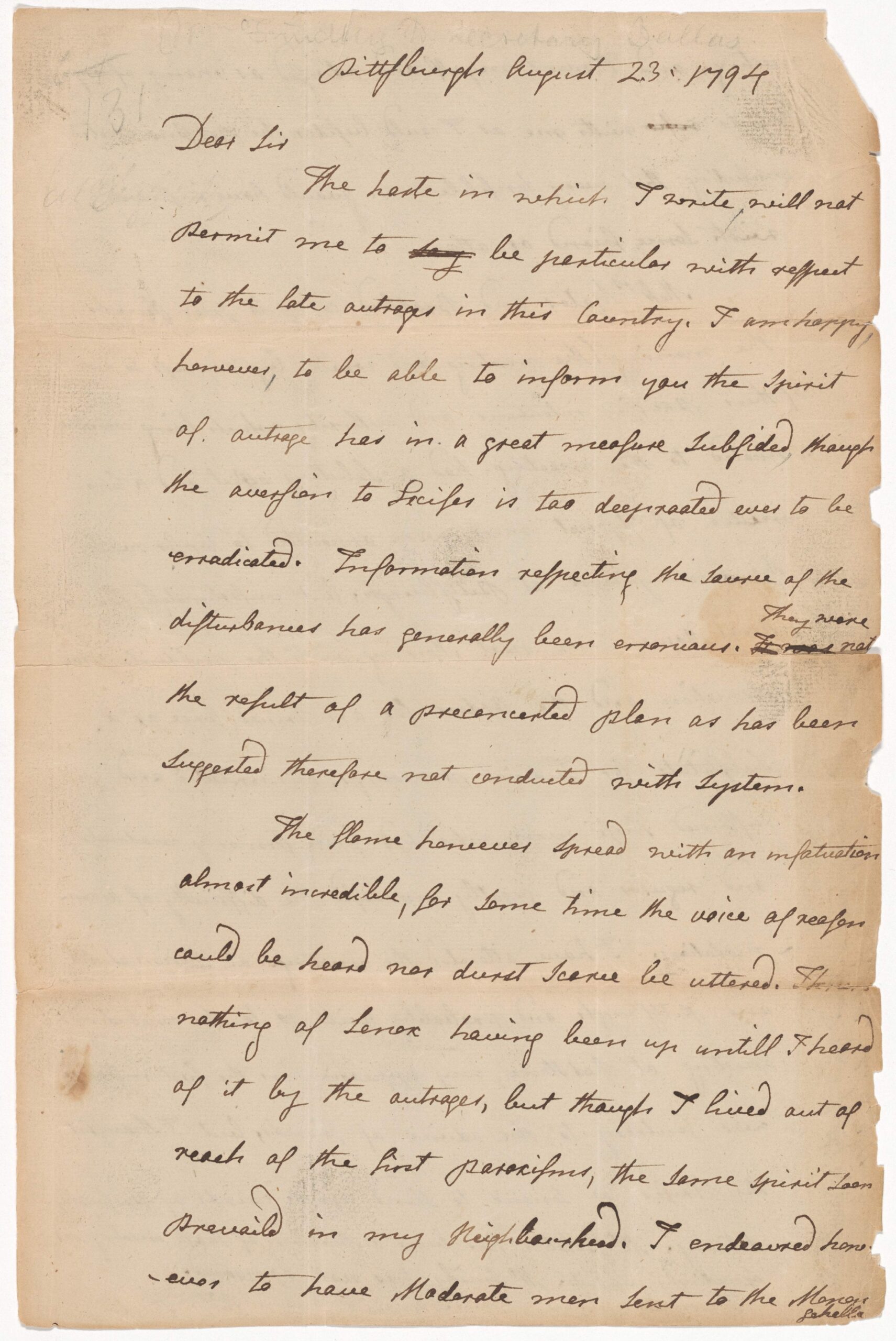

Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, August 23, 26, 28, and September 2, 1794.

LETTER I.

It has from the first establishment of your present constitution been predicted, that every occasion of serious embarrassment which should occur in the affairs of the government – every misfortune which it should experience, whether produced from its own faults or mistakes, or from other causes, would be the signal of an attempt to overthrow it, or to lay the foundation of its overthrow, by defeating the exercise of constitutional and necessary authorities. The disturbances which have recently broken out in the western counties of Pennsylvania furnish an occasion of this sort. It remains to see whether the prediction which has been quoted, proceeded from an unfounded jealousy excited by partial differences of opinion, or was a just inference from causes inherent in the structure of our political institutions. . . .

LETTER II.

. . . The Constitution you have ordained for yourselves and your posterity contains this express clause, “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and Excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States.” You have then, by a solemn and deliberate act, the most important and sacred that a nation can perform, pronounced and decreed, that your Representatives in Congress shall have power to lay Excises. You have done nothing since to reverse or impair that decree.

. . . But the four western counties of Pennsylvania, undertake to rejudge and reverse your decrees[. Y]ou have said, “The Congress shall have power to lay Excises.” They say, “The Congress shall not have this power.” Or what is equivalent – they shall not exercise it: – for a power that may not be exercised is a nullity. Your Representatives have said, and four times repeated it, “an excise on distilled spirits shall be collected.” They say it shall not be collected. We will punish, expel, and banish the officers who shall attempt the collection. We will do the same by every other person who shall dare to comply with your decree expressed in the Constitutional character; and with that of your Representative expressed in the Laws. The sovereignty shall not reside with you, but with us. If you presume to dispute the point by force – we are ready to measure swords with you. . . .

If there is a man among us who shall . . . inculcate directly, or indirectly, that force ought not to be employed to compel the Insurgents to a submission to the laws, if the pending experiment to bring them to reason (an experiment which will immortalize the moderation of the government) shall fail; such a man is not a good Citizen; such a man however he may prate and babble republicanism, is not a republican; he attempts to set up the will of a part against the will of the whole, the will of a faction, against the will of nation, the pleasure of a few against your pleasure; the violence of a lawless combination against the sacred authority of laws pronounced under your indisputable commission.

Mark such a man, if such there be. The occasion may enable you to discriminate the true from pretended Republicans; your friends from the friends of faction. ‘Tis in vain that the latter shall attempt to conceal their pernicious principles under a crowd of odious invectives against the laws. Your answer is this: “We have already in the Constitutional act decided the point against you, and against those for whom you apologize. We have pronounced that excises may be laid and consequently that they are not as you say inconsistent with Liberty. Let our will be first obeyed and then we shall be ready to consider the reason which can be afforded to prove our judgement has been erroneous. . . . We have not neglected the means of amending in a regular course the Constitutional act. . . . In a full respect for the laws we discern the reality of our power and the means of providing for our welfare as occasion may require; in the contempt of the laws we see the annihilation of our power; the possibility, and the danger of its being usurped by others & of the despotism of individuals succeeding to the regular authority of the nation.”

That a fate like this may never await you, let it be deeply imprinted in your minds and handed down to your latest posterity, that there is no road to despotism more sure or more to be dreaded than that which begins at anarchy.

LETTER III.

If it were to be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of security in a Republic? the answer would be, An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws – the first growing out of the last. It is by this, in a great degree, that the rich and powerful are to be restrained from enterprises against the common liberty – operated upon by the influence of a general sentiment, by their interest in the principle, and by the obstacles which the habit it produces erects against innovation and encroachment. It is by this, in a still greater degree, that caballers, intriguers, and demagogues are prevented from climbing on the shoulders of faction to the tempting seats of usurpation and tyranny.

. . . Government is frequently and aptly classed under two descriptions, a government of force and a government of laws; the first is the definition of despotism – the last, of liberty. But how can a government of laws exist where the laws are disrespected and disobeyed? Government supposes controul. It is the power by which individuals in society are kept from doing injury to each other and are bro’t to co-operate to a common end. The instruments by which it must act are either the authority of the Laws or force. If the first be destroyed, the last must be substituted; and where this becomes the ordinary instrument of government there is an end to liberty.

Those, therefore, who preach doctrines, or set examples, which undermine or subvert the authority of the laws, lead us from freedom to slavery; they incapacitate us for a government of laws, and consequently prepare the way for one of force, for mankind must have government of one sort or another.

There are indeed great and urgent cases where the bounds of the constitution are manifestly transgressed, or its constitutional authorities so exercised as to produce unequivocal oppression on the community, and to render resistance justifiable. But such cases can give no color to the resistance by a comparatively inconsiderable part of a community, of constitutional laws distinguished by no extraordinary features of rigor or oppression, and acquiesced in by the body of the community.

Such a resistance is treason against society, against liberty, against everything that ought to be dear to a free, enlightened, and prudent people. To tolerate were to abandon your most precious interests. Not to subdue it, were to tolerate it. . . .

LETTER IV.

. . . Fellow Citizens – You are told, that it will be intemperate to urge the execution of the laws which are resisted – what? will it be indeed intemperate in your Chief Magistrate, sworn to maintain the Constitution, charged faithfully to execute the Laws, and authorized to employ for that purpose force when the ordinary means fail – will it be intemperate in him to exert that force, when the constitution and the laws are opposed by force? Can he answer it to his conscience, to you not to exert it?

Yes, it is said; because the execution of it will produce civil war, the consummation of human evil.

Fellow-Citizens – Civil War is undoubtedly a great evil. It is one that every good man would wish to avoid, and will deplore if inevitable. But it is incomparably a less evil than the destruction of Government. The first brings with it serious but temporary and partial ills – the last undermines the foundations of our security and happiness – where should we be if it were once to grow into a maxim, that force is not to be used against the seditious combinations of parts of the community to resist the laws? . . . The Hydra Anarchy would rear its head in every quarter. The goodly fabric you have established would be rent assunder, and precipitated into the dust. . . . You know that the power of the majority and liberty are inseparable – destroy that, and this perishes. . . .

Tully.

Annual Message to Congress (1794)

November 19, 1794

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.