No related resources

Introduction

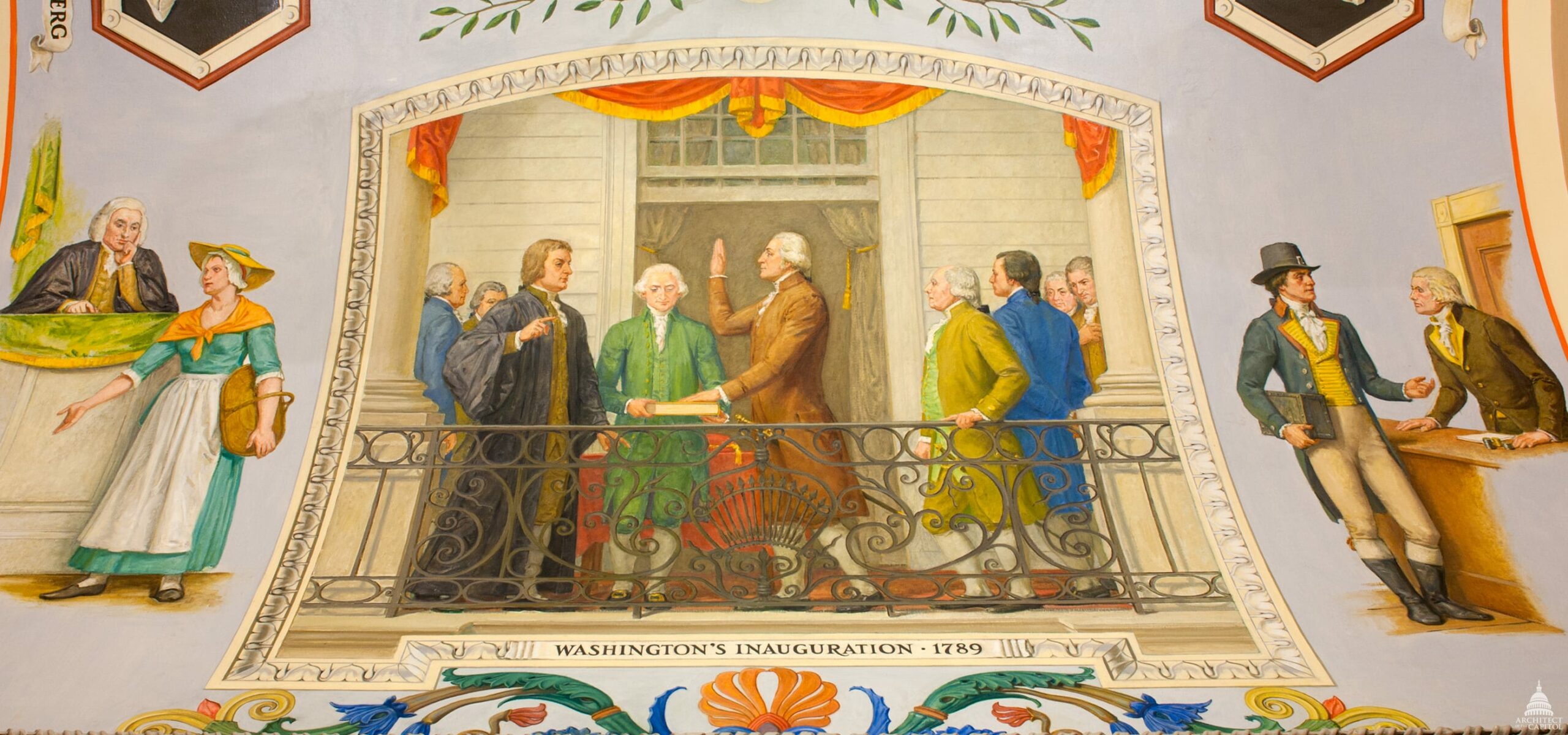

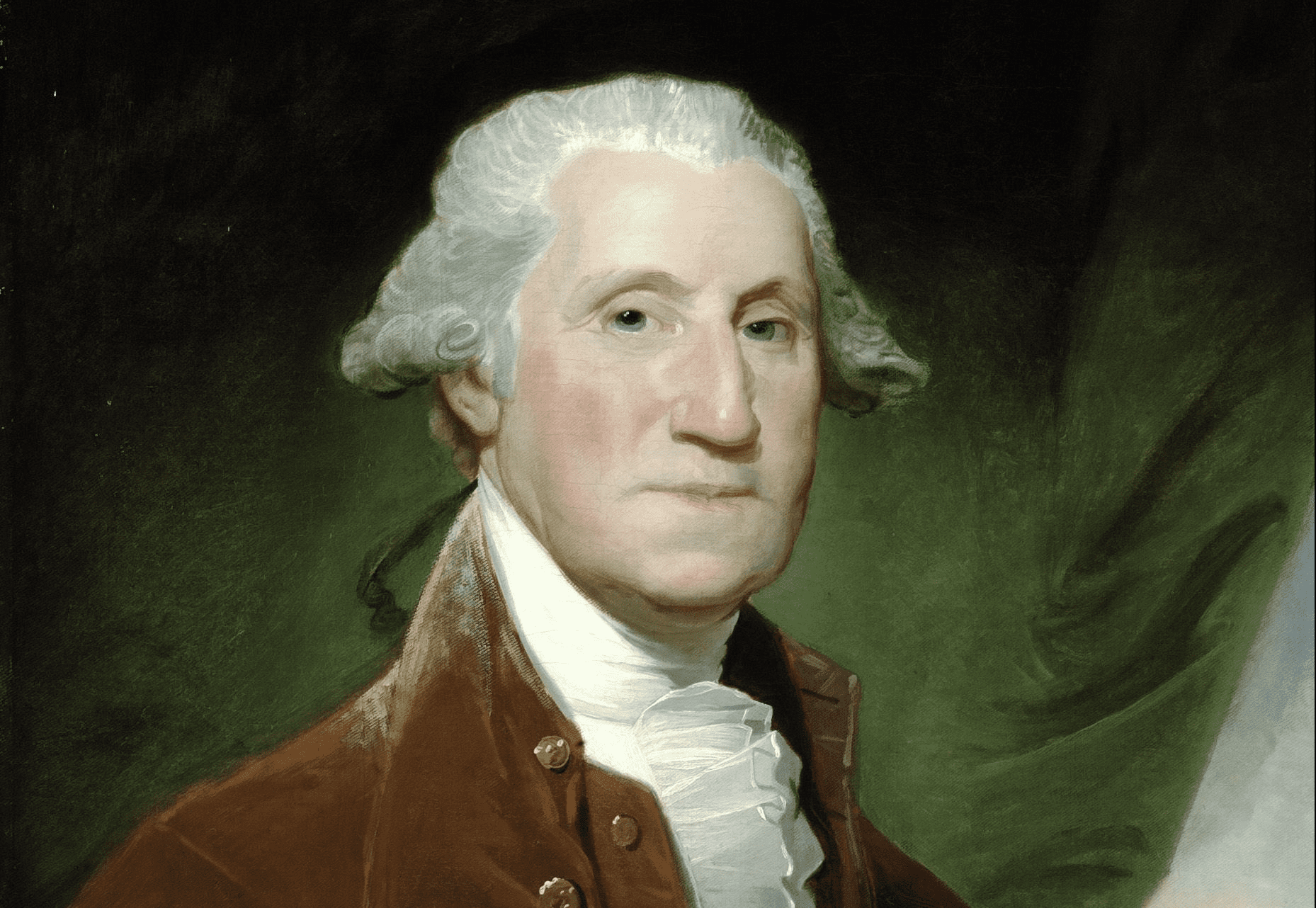

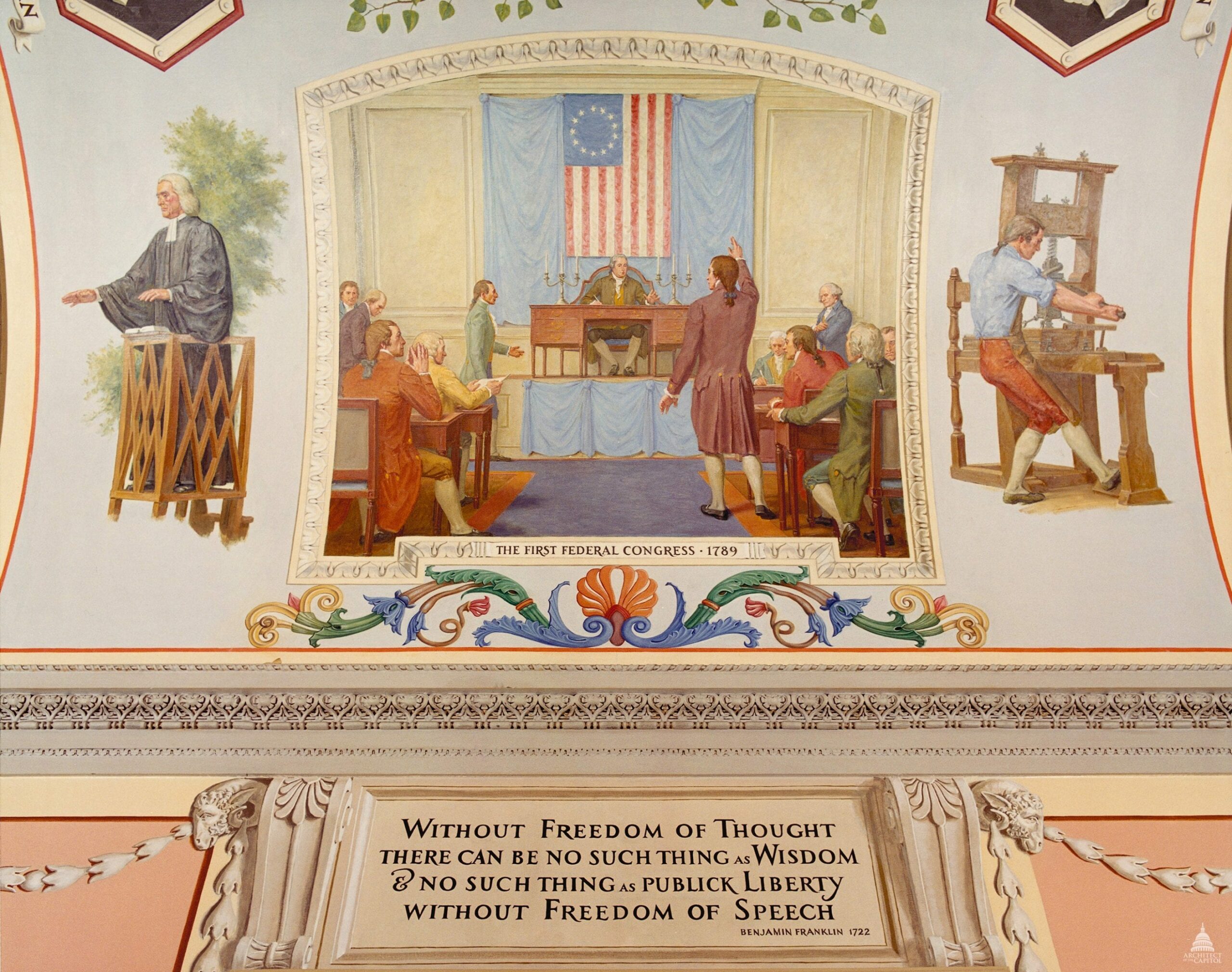

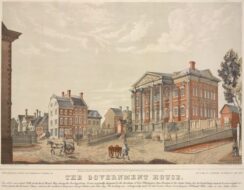

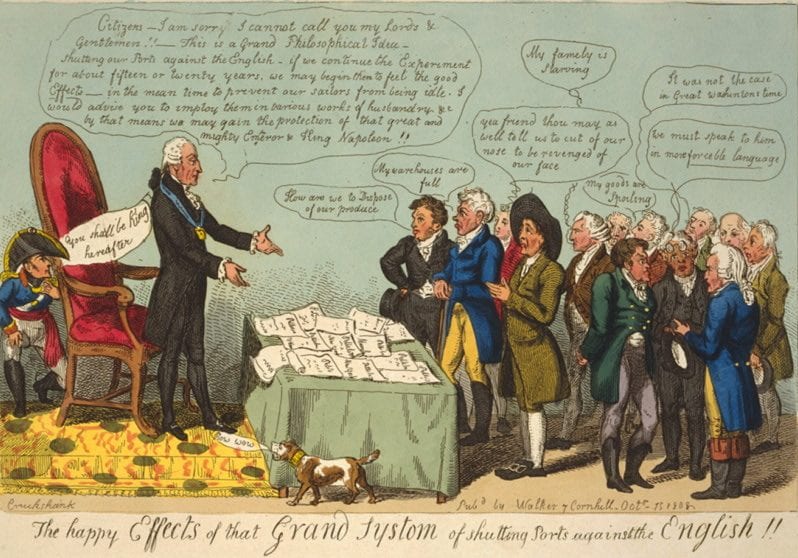

During its early years, Congress was a relatively chaotic assembly lacking highly organized political parties, committees, or central leadership. Consequently, officials in the executive branch were often able to set the legislative agenda by sending over reports and suggestions to be discussed by Congress.

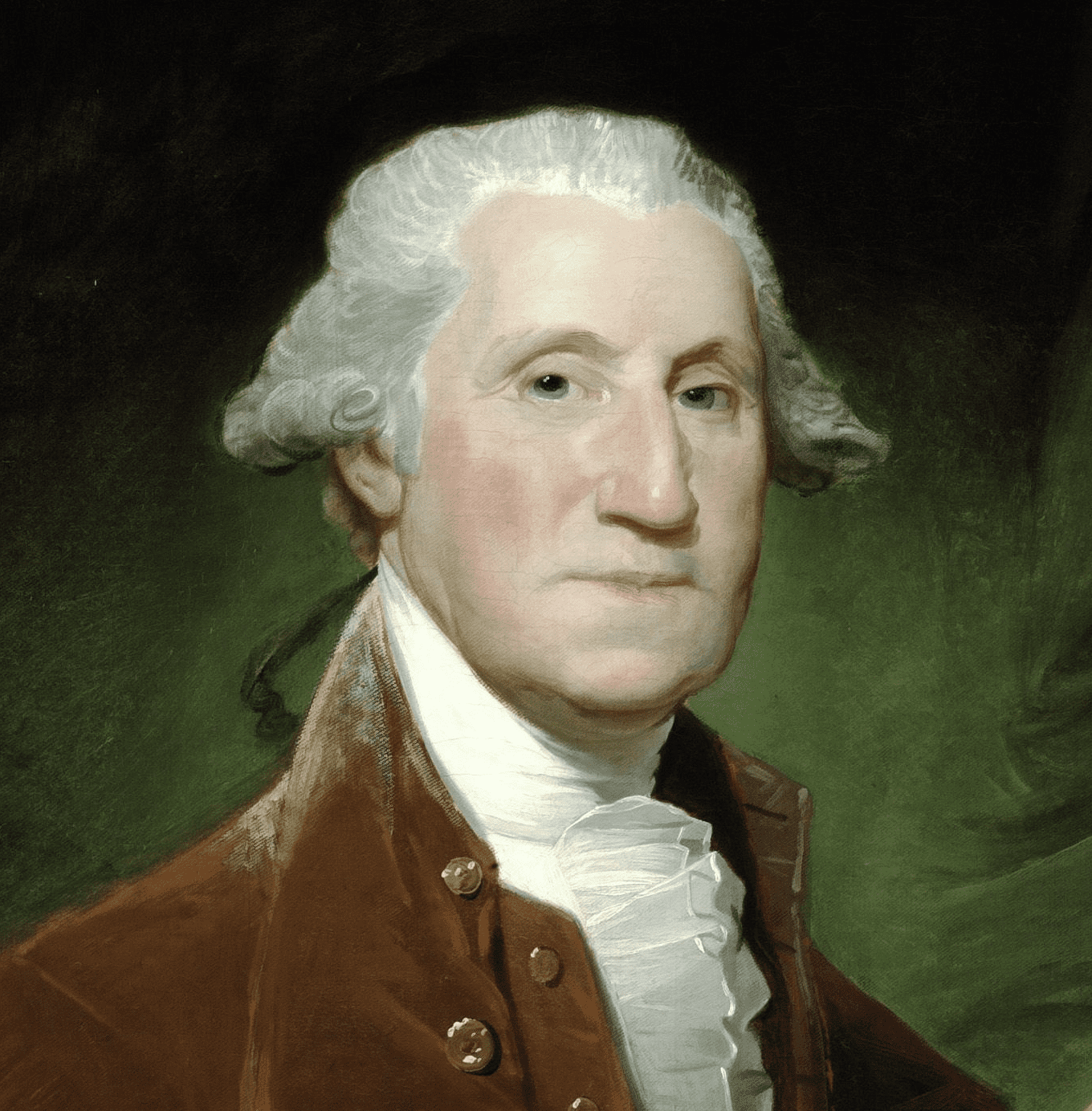

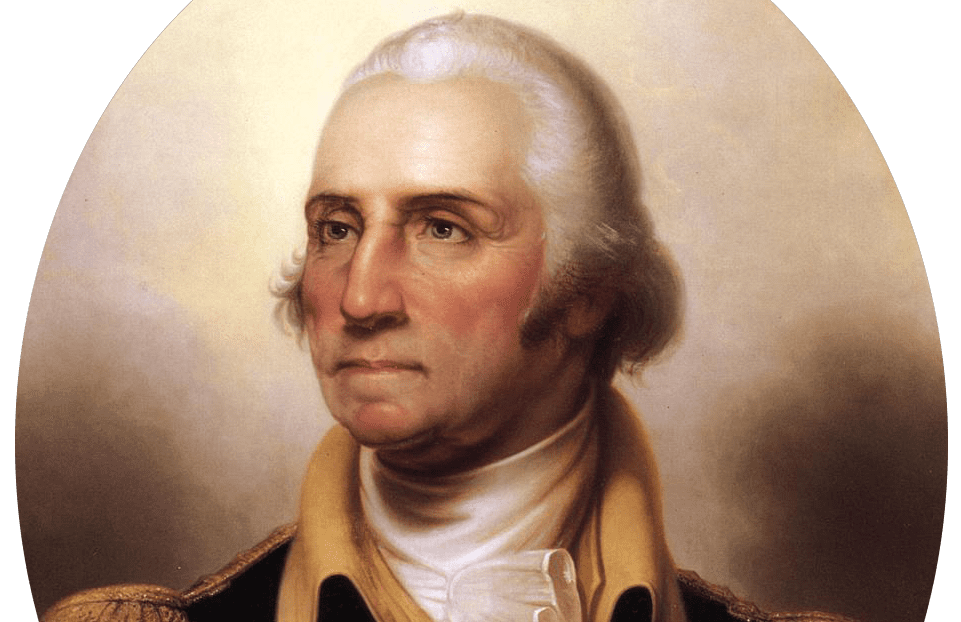

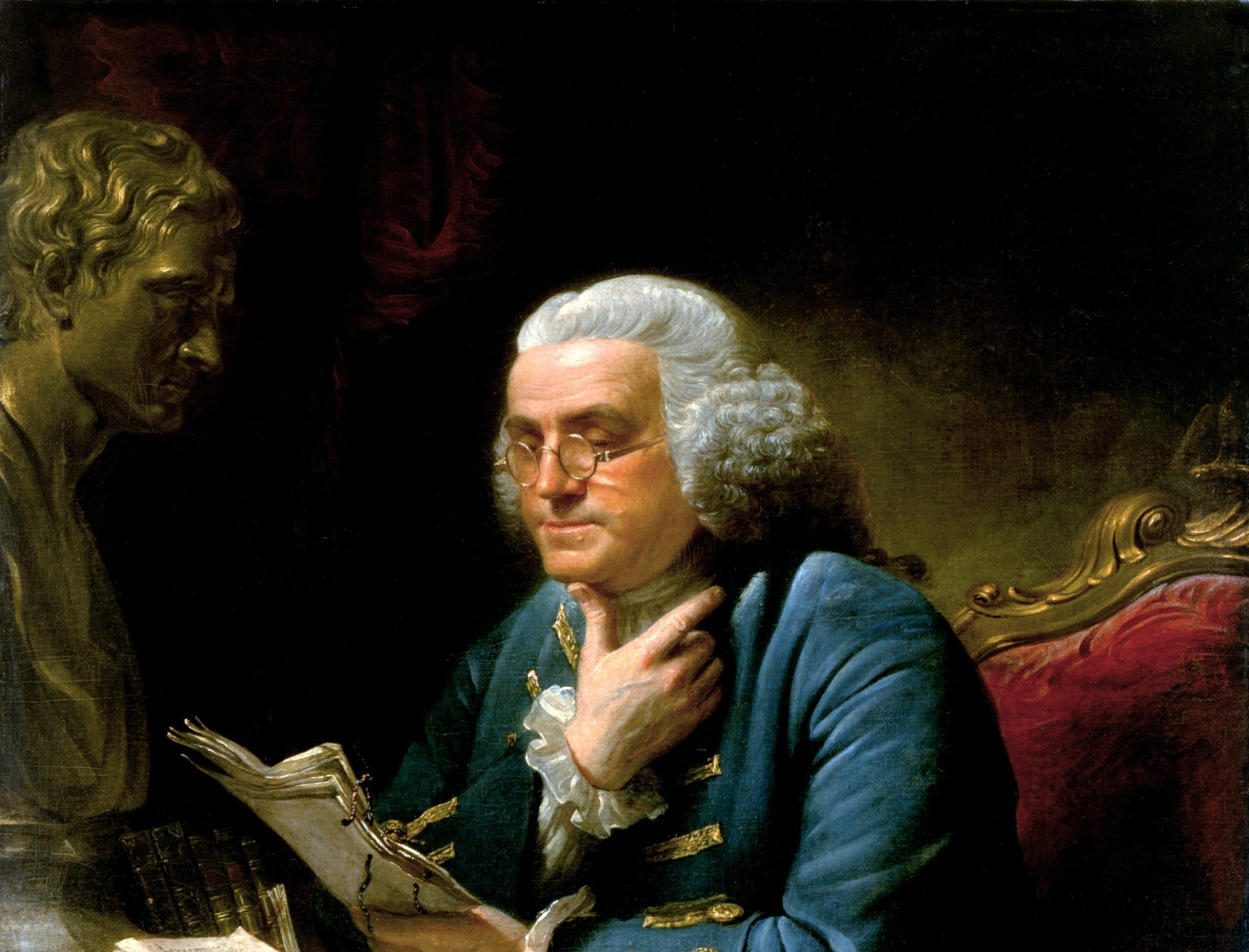

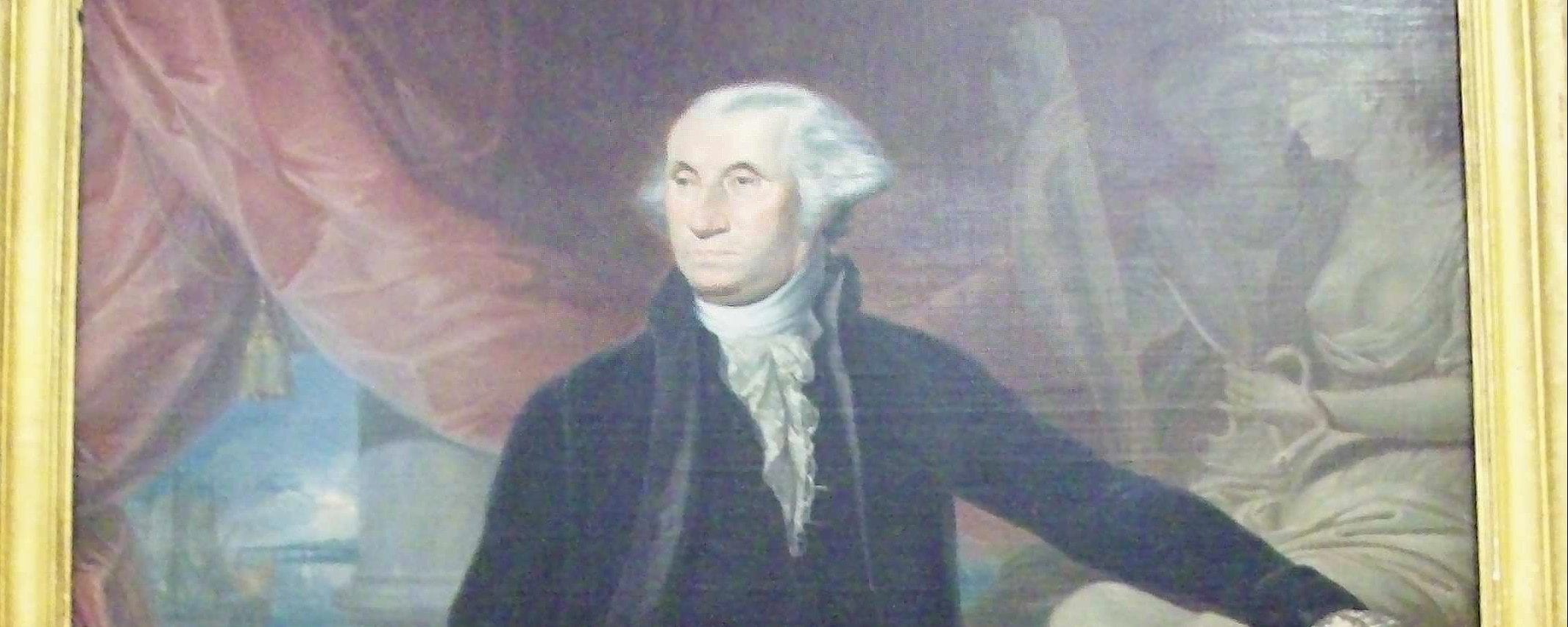

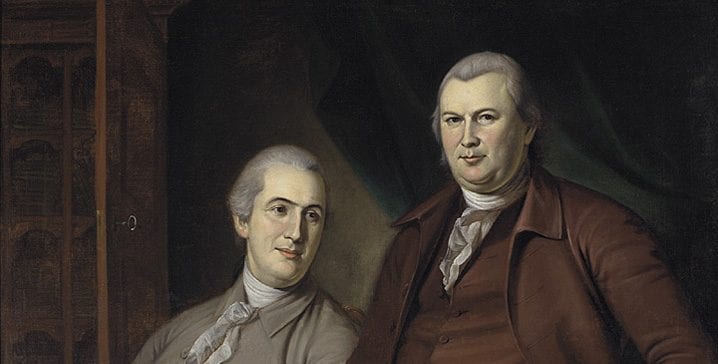

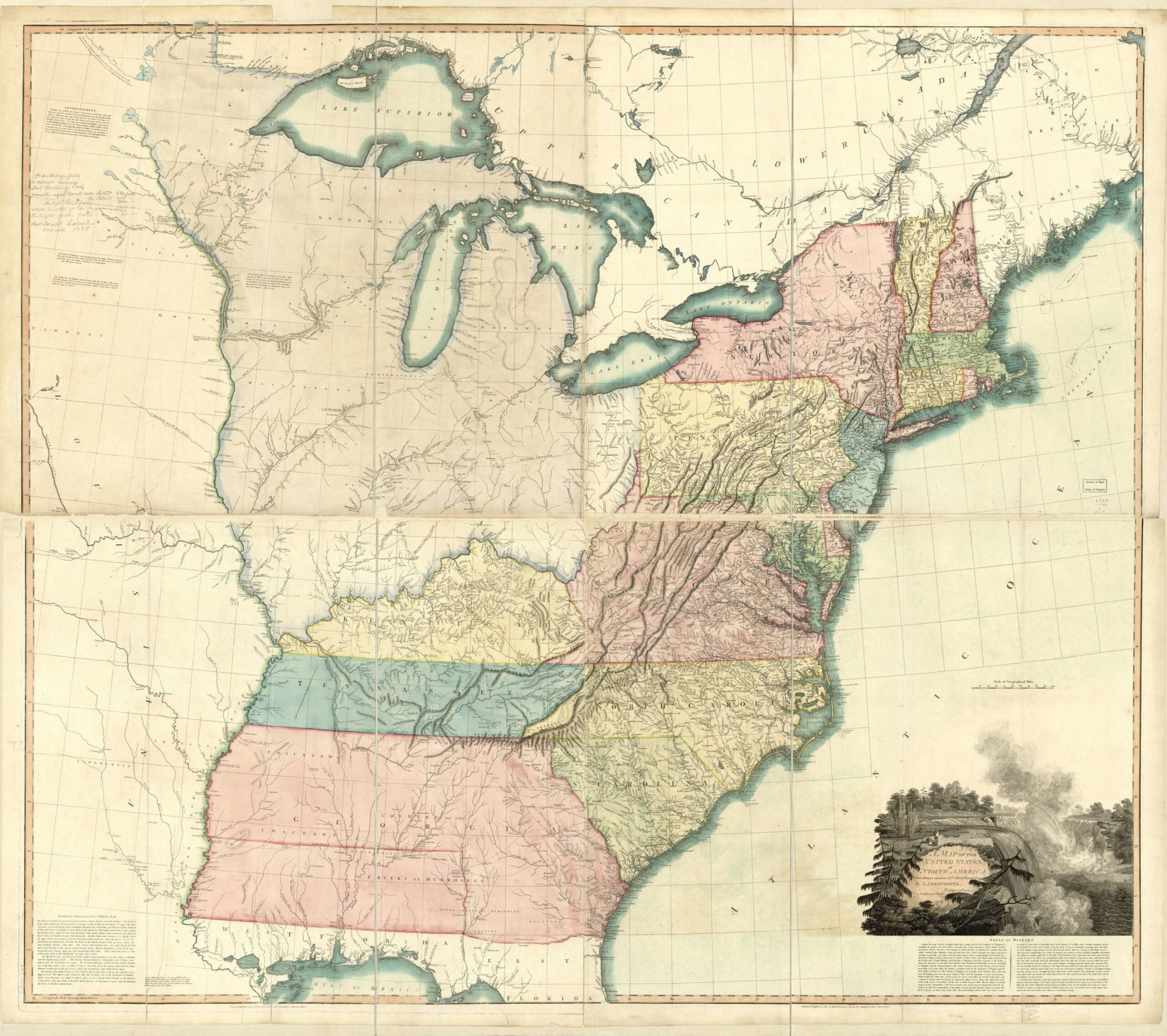

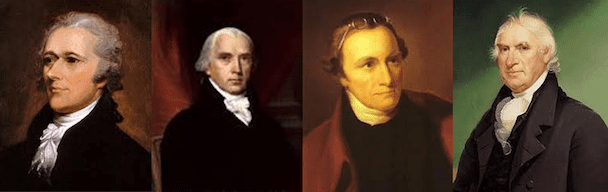

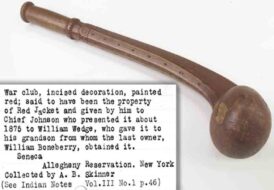

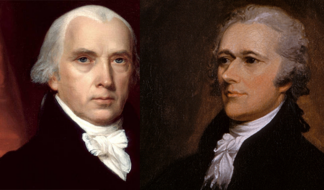

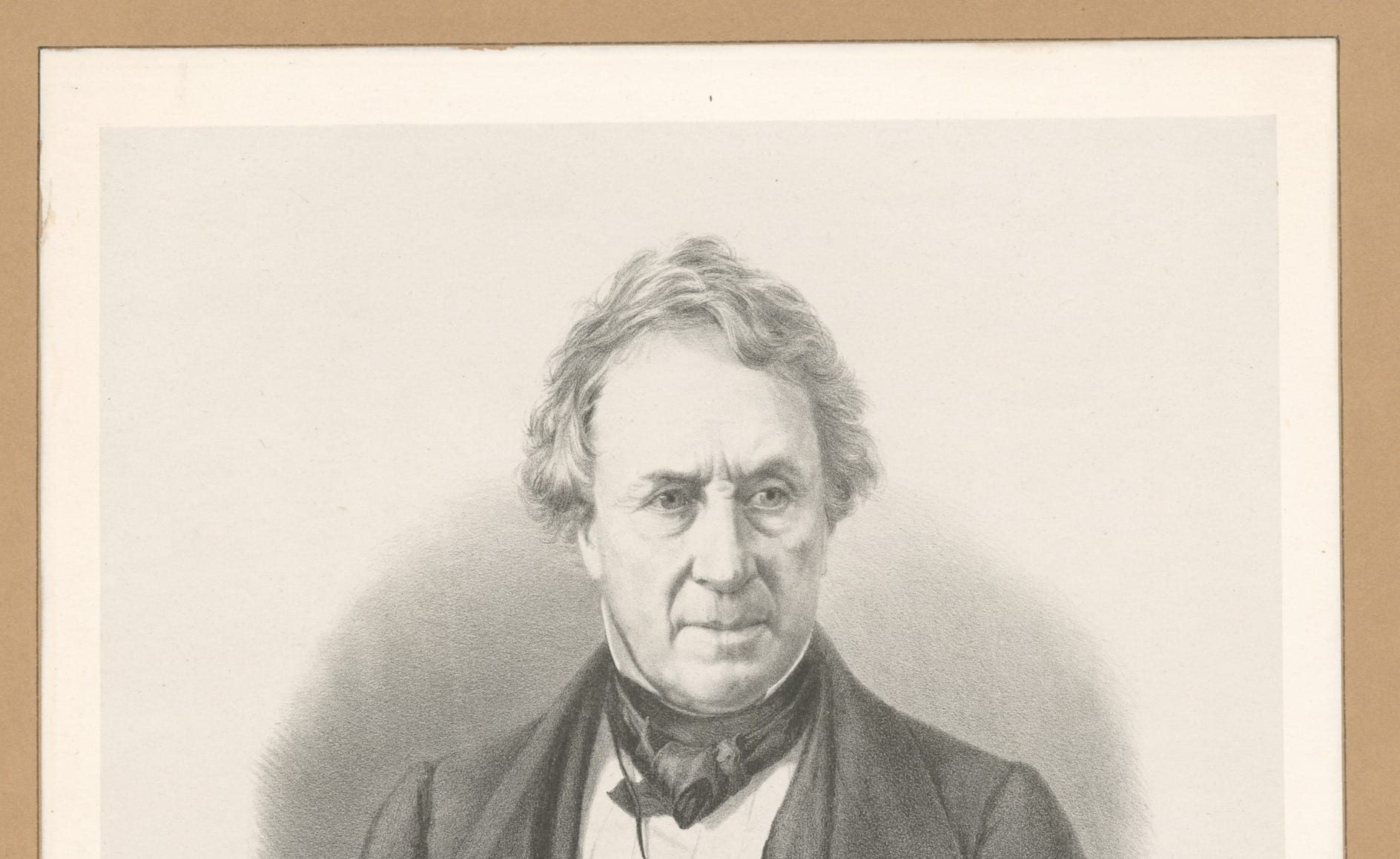

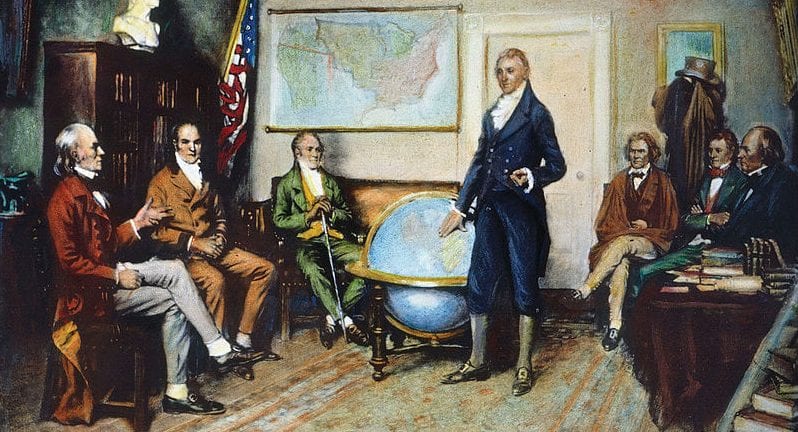

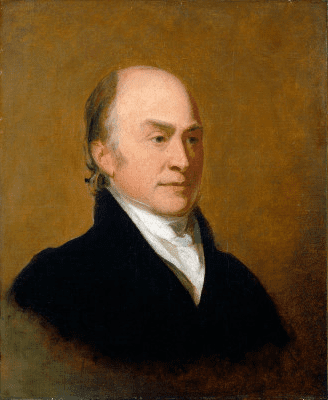

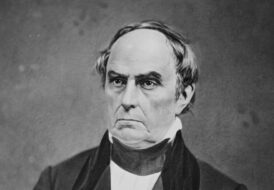

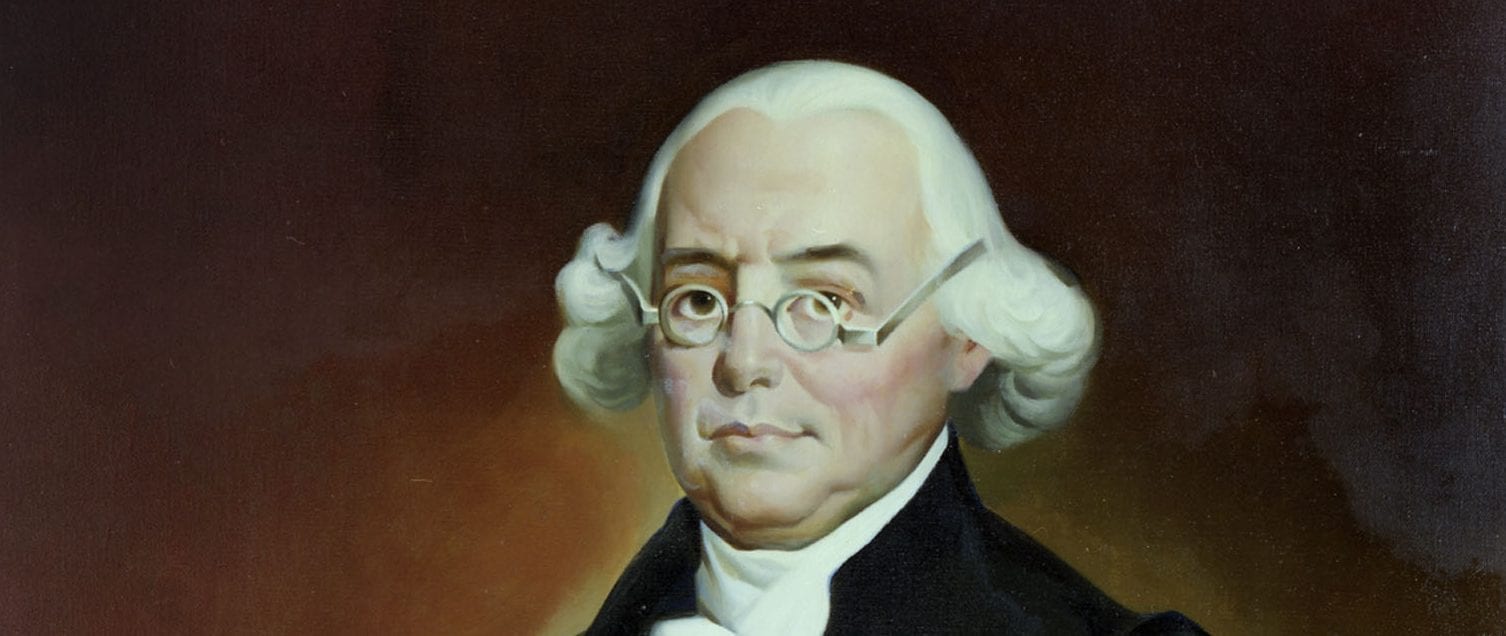

Nobody influenced the legislative agenda more during George Washington’s presidency than Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804). Hamilton’s various plans for funding the Revolutionary War debt, establishing a national bank, and promoting domestic manufacturers were highly controversial, both because of the policies themselves and because the executive branch was, according to Hamilton’s opponents, encroaching upon the legislative powers of Congress.

In this debate from Congress’ early years, a member introduced a resolution to ask Hamilton to draft a proposal for Congress’ consideration. The members then debated whether it was appropriate for members of the executive branch to influence the deliberations of Congress.

Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 2nd Congress, 2nd session, pp. 695–722.

[November 19, 1792]

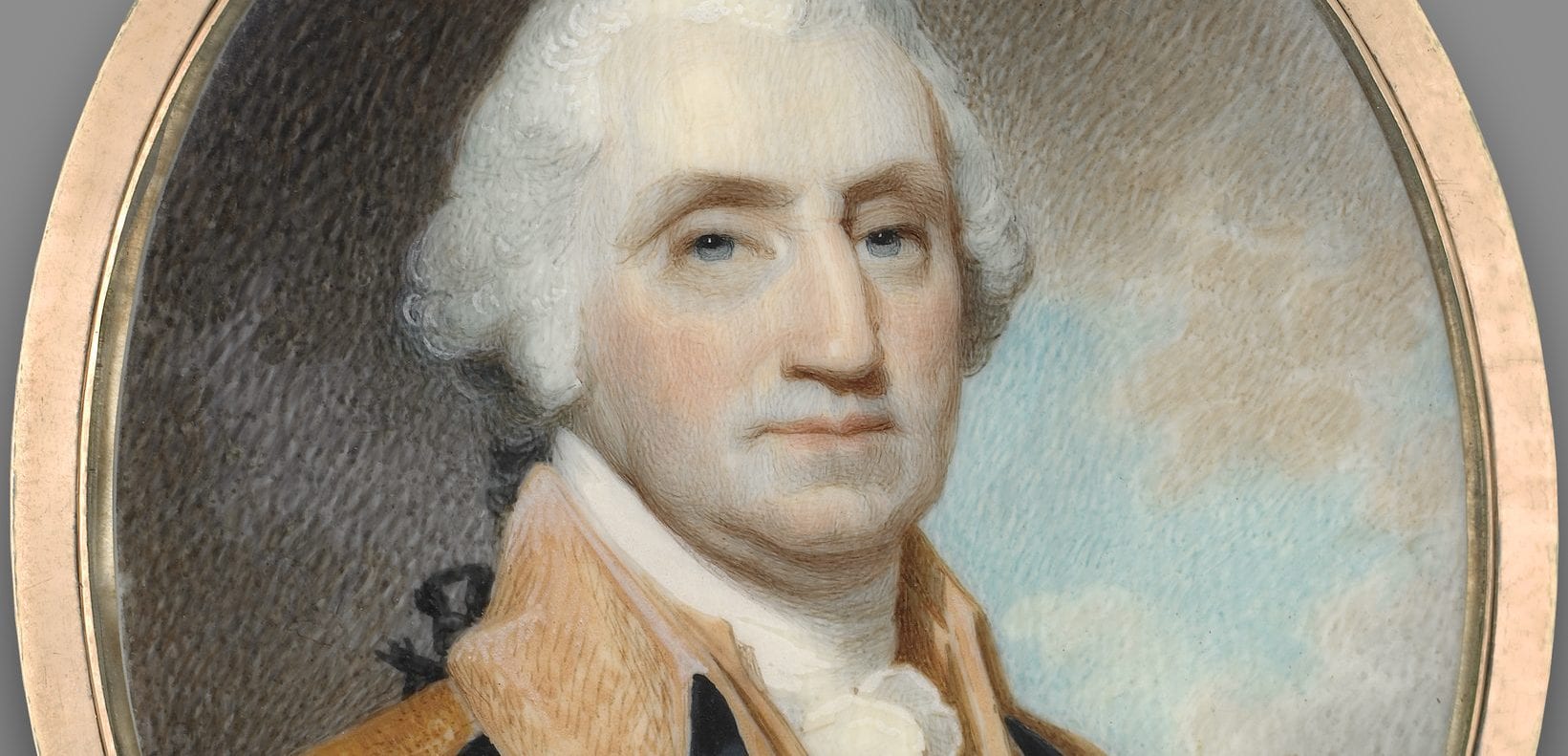

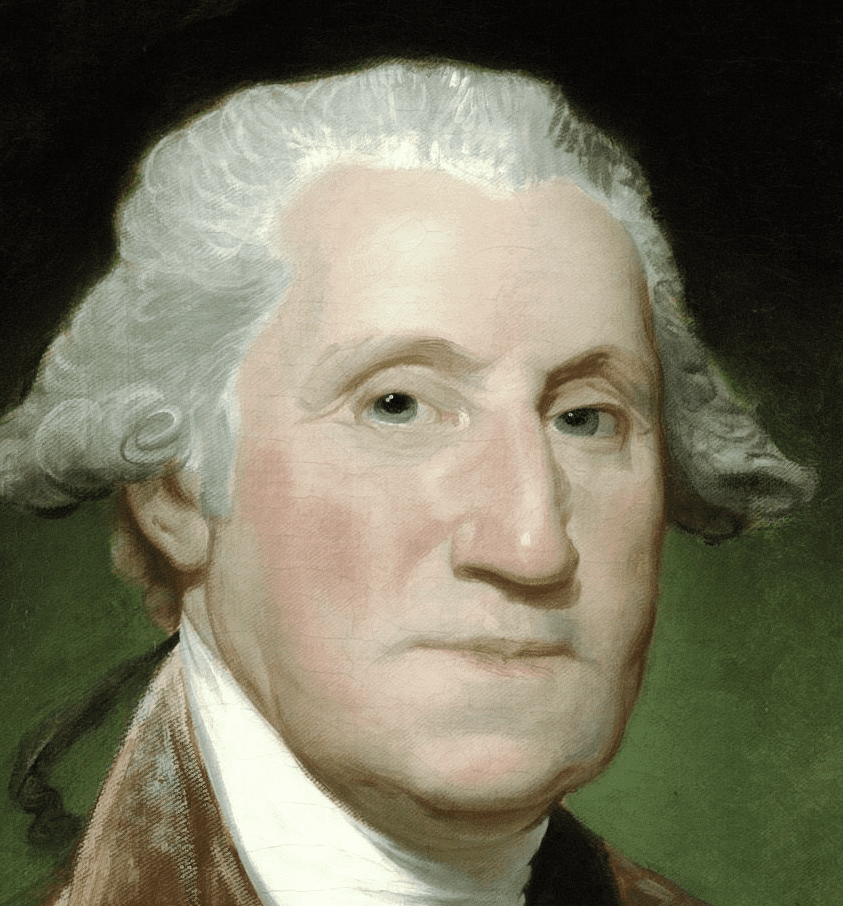

The House again resolved itself into a Committee of the Whole House on the Speech of the President of the United States to both Houses of Congress.1

On that part which relates to the reduction of the public debt, Mr. Fitzsimons2 offered a resolution to the following purport:

“Resolved, As the opinion of this committee, that measures for the reduction of so much of the public debt as the United States have a right to redeem, ought to be adopted; and that the secretary of the Treasury be directed to report a plan for the purpose.”. . .

Mr. Mercer.3 No question, he conceived, was of more importance than that involved in the motion before the House. . . . He conceived it improper to commit to any man what he was bound to himself to do. He conceived the power of the House to originate plans of finance, to lay new burdens on the people entrusted to them by their constituents, as incommunicable.4…

Mr. Smith,5 of South Carolina . . .made some reply to the objections of the gentleman last up, to that part of the motion which contemplated a reference to the secretary of the Treasury. The ultimate decision, he remarked, in no one point, was relinquished by such a reference. If such a reference was unconstitutional, he observed, much business had been conducted in the House in an unconstitutional manner, by repeated references to the heads of departments.6 The reference of business to select committees would be unconstitutional, he said, on the same ground. . . .

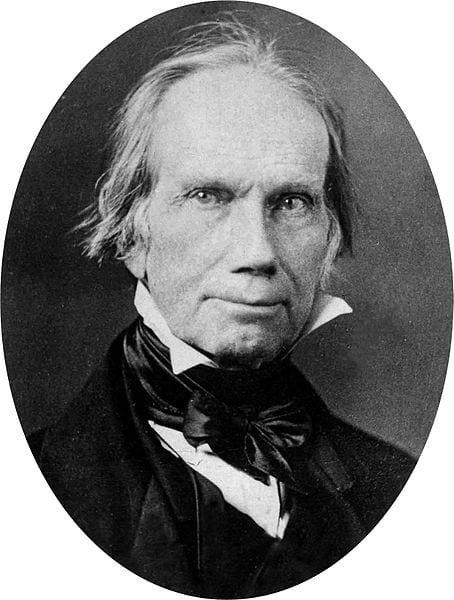

Mr. Madison7 drew a distinction between the deliberative functions of the House and the ministerial functions of the executive powers. The deliberative functions, he conceived, should be first exercised before the ministerial began to act. It should be decided by the House, in the first instance, he conceived, whether the debt should be reduced by imposing new taxes, or by varying the burdens, or by new loans. The fundamental principles of any measure, he was of opinion, should be decided in the House, perhaps even before a reference to a select committee. He did not pretend to determine whether the motion now before the House might not involve a reference of a ministerial nature merely. . . .

Mr. Hilhouse8 was a different opinion. His constituents, he conceived, expected their business to be done in the best manner possible, and that he should not rely on his own information only, but endeavor to avail himself of the information of others. He said he should consider himself unequal to the task of taking a share in legislating for the Union if he was to depend on his own information alone. He expected to derive information from every source. It was the intention of meeting in Congress to collect information from every quarter. . . .

Mr. Murray9 observed that the debate on the propriety of referring to the secretary of the Treasury the business contemplated in the motion, had produced but few new arguments; it was a repetition of what was said when the subject was before the House at another time. One new idea, however, he observed, had fallen from the gentleman from Virginia [Mr. Madison], viz.: his distinction between deliberative and ministerial functions. This distinction, he conceived, is qualified by the nature of things. It is qualified, in this instance, by the law which establishes the Treasury Department. That law makes it the duty of the secretary to digest and report plans to ameliorate our finances, without any call from the House. True, the business of the House is to deliberate; but, by references, neither is the power of the House to deliberate infringed, nor does it give the secretary a right legislatively to deliberate, but to deliberate ministerially; and it was important, he conceived, in a government framed like ours, that such officers should have the power to deliberate in that manner. The result of their deliberations was not obligatory on the House, no further than it was warranted by wisdom. . . .

Mr. Madison saw some difficulty in drawing the exact line between subjects of legislative and ministerial deliberations, but still such a line most certainly existed. Gentlemen who argued the propriety of calling on the secretary for information, plans, and propositions involved the propriety of permitting that officer, in the shape of a plan or measure, to propose a new tax, and say whether it should be a direct or indirect one. Yet, if it was proposed directly to give this power to the secretary, few members, he believed, would agree to it. He was in favor of striking out [the request for the secretary of the Treasury to submit a plan to Congress]. . . .

[November 20, 1792]

The House again resolved itself into a Committee of the Whole House on the Speech of the President of the United States to both Houses of Congress.

Mr. Baldwin10 expressed reluctance in being obliged to rise on the present occasion, but the striking out the latter part of the proposition became indispensable in order to defeat the dangerous doctrine of precedents, and prevent a future plea on the ground of construction.11 He was aware of the consequences, and that the practice, unless it should be relinquished, would lead to no good.

When gentlemen talk of light and information only, he would agree with them, for he wished to obtain it from every proper source. If has been made the duty of the executive departments to give information to the legislature, but this information should relate, merely, in his opinion, to statements of facts and details of business, but the laws should be framed by the legislature, after they had acquired this information. . . .

There is a material distinction between receiving information on which to ground a law, and a plan of the law ready formed. The latter mode he was opposed to. Gentlemen have said that we may reject what is proposed; but in this case we will only be exercising a sort of revisionary power, very different from a legislative one; a very material difference from what is contemplated in the Constitution—the difference between originating and possessing only the right of a negative.

The propriety of keeping the legislative, judicial, and executive powers distinct from each other is founded in good sense. It is dangerous to entrust those who have a prospect of deriving some advantage in the execution of a law to have any hand in framing it. And it is as improper for the legislative to attend to the execution of a law, as it is for the executive to meddle in the business of legislation. The principles, if once admitted, may be carried to such lengths as to admit the judiciary to sit in the House of Representatives; and we shall have them here, in their long robes, introducing plans of laws, with the secretaries of the Treasury and War Departments. The strong sense he had of the necessity of keeping the departments distinct had such force upon his mind as to occasion his opposition even to the introduction of the two secretaries, the other day, to answer interrogatories in the House. Such a precedent, he feared, might prove a dangerous one and lean to an interference in more important points.

Upon the whole, he was against the reference and wished that part of the motion to be struck out. . . .

[T]he question for striking out the latter part of the resolution was called for, and there rose in the affirmative 25, and 31 in the negative.

The Committee then rose, reported the resolution, and the House adjourned.

[November 21, 1792] | The President’s Speech

The House proceeded to consider the resolutions reported yesterday by the Committee of the Whole House on the Speech of the President of the United States. . . .

[A] motion was made, and, the question being put to amend the same, by striking out the words “and that the secretary of the Treasury be directed to report a plan for” [reducing the national debt]. . . .

Mr. Laurance12 spoke for some time in reply to the arguments yesterday adduced by those who had called the mode of referring to the heads of departments unconstitutional. He insisted that there was nothing coming from the secretary of the Treasury which partook of a legislative quality; and, with regard to the plans heretofore proposed by that officer, he was of opinion that they had met with general approbation, and that they had materially assisted the credit of the United States. . . .

Mr. Findley13 was against it. . . .

It is the constitutional duty of the president to inform the legislature respecting the state of the Union, and to recommend such legislative business as he may think expedient. The institutions of the heads of the various executive departments are authorized in the Constitution, and have been organized by law. They are the proper executive channels through which information respecting the execution and practical defects in the laws are to be collected, and with whom the necessary vouchers are deposited; and from those we have a right to call for such information as is necessary. . . .

Mr. Madison closed the debate with a few powerful observations. He insisted that a reference to the secretary of the Treasury on subjects of loans, taxes, and provision for loans, &c., was, in fact, a delegation of the authority of the legislature, although it would admit of much sophistical argument to the contrary. The arguments which he had heard, he said, were not satisfactory to his mind; and he peremptorily denied that the plans of that officer came into the House in either an equitable or unbiased manner. . . .[I]t was evident the secretary’s plans were not introduced in such manner as to leave the House the freedom of exercising their own understandings in a proper constitutional manner.

When Mr. Madison sat down, the question was taken on striking out the latter part of the motion, to wit: for referring to the secretary of the Treasury to report a plan, etc., and it passed in the negative: yeas 25, nays 32.

[Therefore, the provision asking Alexander Hamilton to send a plan to the Congress for reducing the national debt was retained.]

- 1. President George Washington delivered his Fourth Annual Message to Congress on November 6, 1792. Topics discussed included hostilities between Native American tribes and the United States; the development of a U.S. mint; and provision for the public debt.

- 2. Thomas Fitzsimons (1741–1811) was a member of the Pennsylvanian delegation to the Constitutional Convention and a signee of the U.S. Constitution. Fitzsimons was elected to the First, Second, and Third Congresses, and ran an unsuccessful reelection campaign to represent Pennsylvania’s “at-large” district for the Fourth Congress. He went on to become president of the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce and founded and directed the Bank of North America.

- 3. John Francis Mercer (1759–1821), a member of the Anti-Administration Party, represented Virginia in the Second and Third Congresses. He served in the House from 1792—filling the vacancy of William Pinkney—until 1794. Like Pinkney, Mercer resigned from office and returned to state politics.

- 4. Nontransferable.

- 5. William Loughton Smith (1758–1812) was a representative from South Carolina who was among the most active participants in the debates of the First Congress. He drafted the nation’s first bankruptcy legislation.

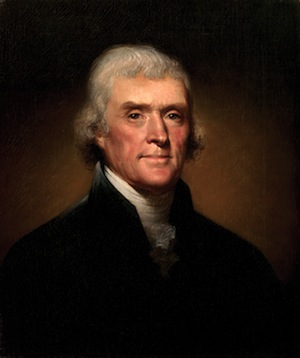

- 6. “Heads of departments” led different executive branch departments, such as Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) at the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), the secretary of state.

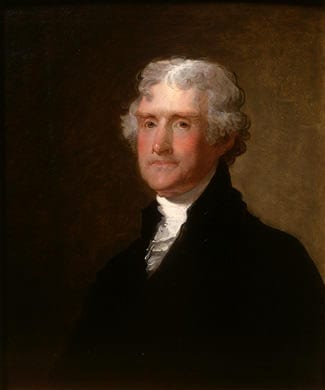

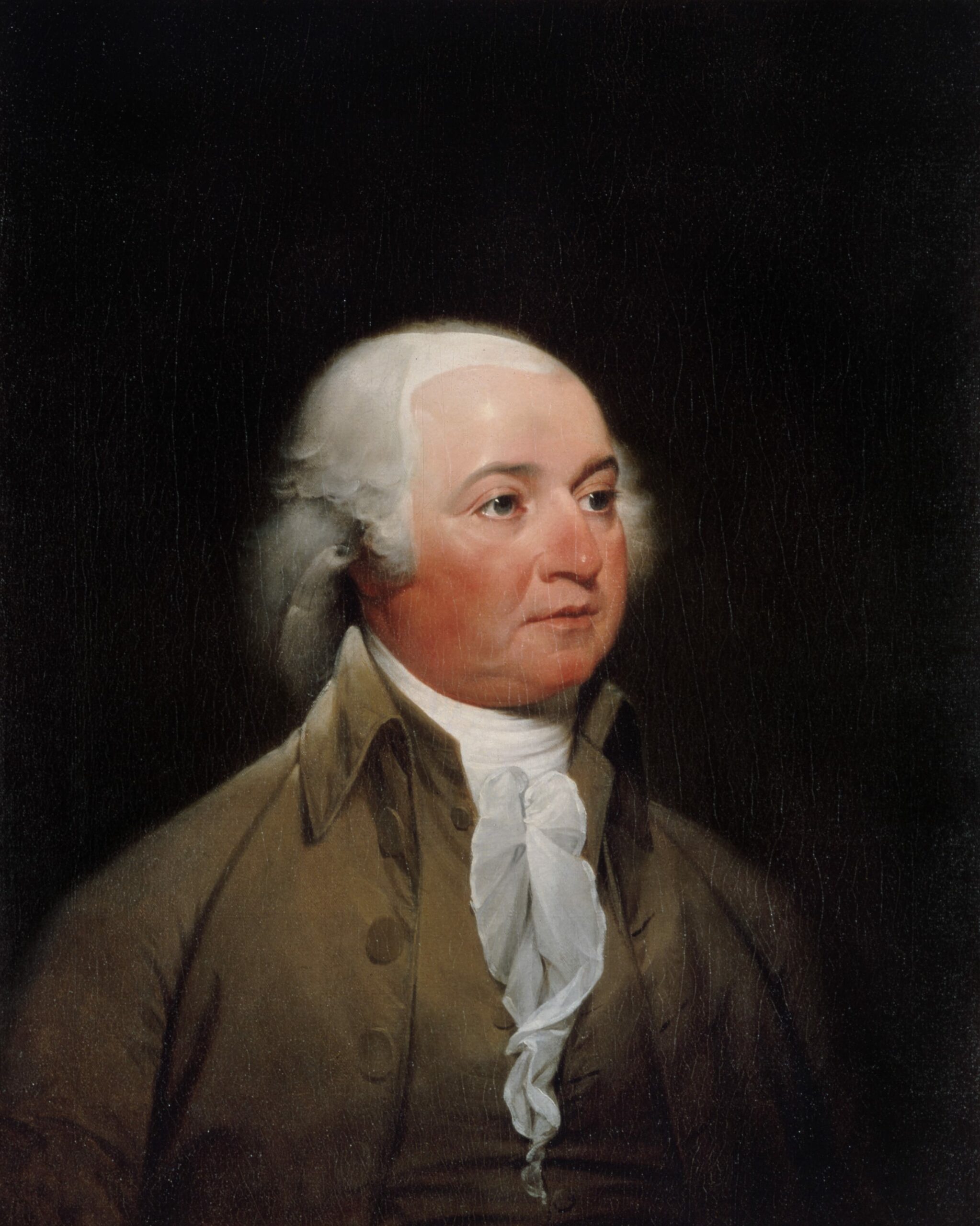

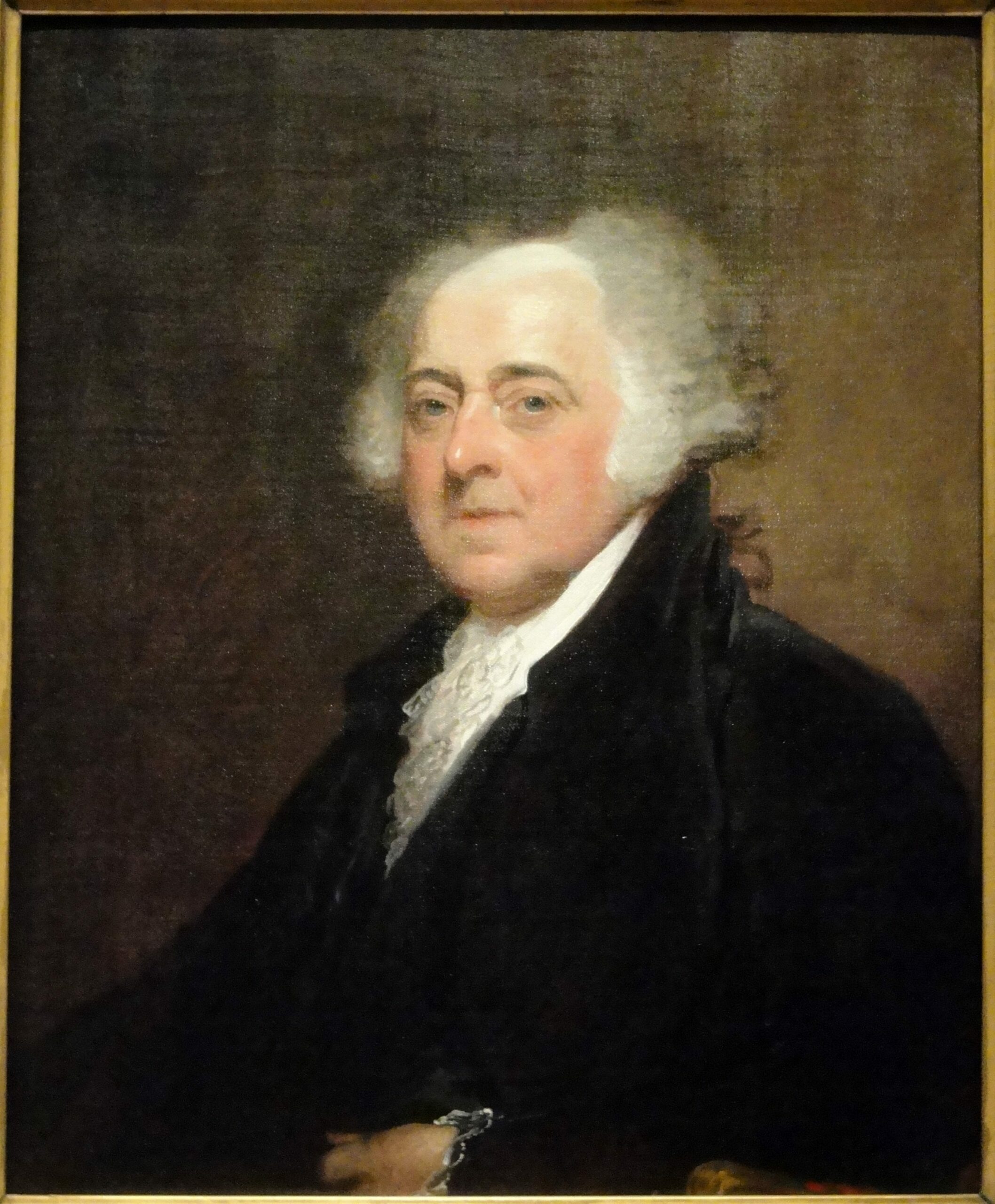

- 7. James Madison (1751–1836), a representative from Virginia, is widely known as the “Father of the Constitution” due to his contributions at the Convention. He coauthored the Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and also served as secretary of state and as the fourth president of the United States.

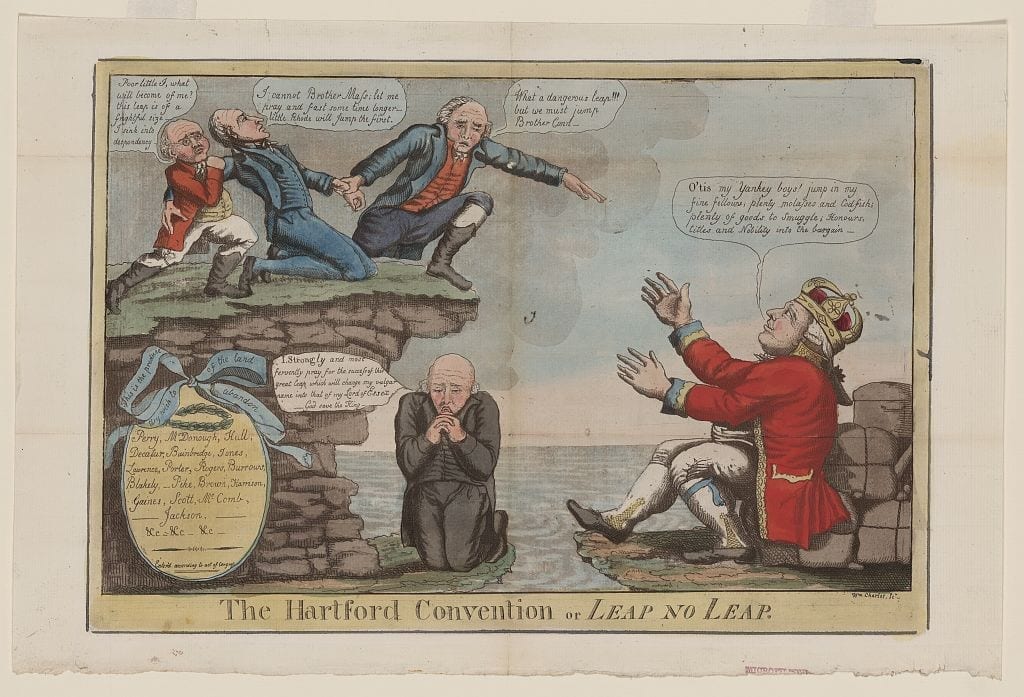

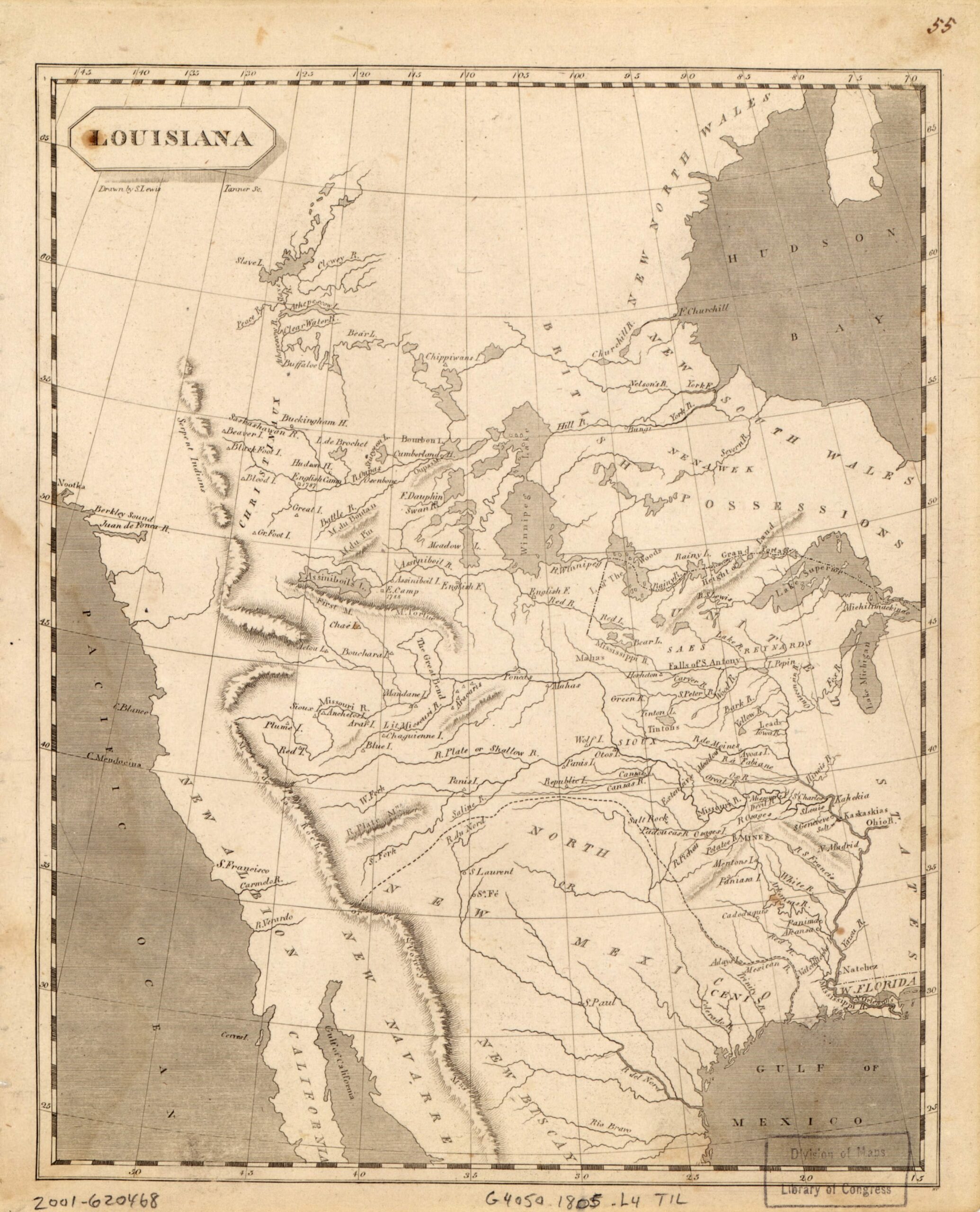

- 8. James Hillhouse (1754–1832) represented Connecticut in both houses of Congress. He served in the House from 1791 until he resigned in 1796 to fill a vacancy in the Senate. Elected to the Senate that same year, Hillhouse represented Connecticut until 1810. Hillhouse was one of several New England politicians who proposed that the region secede from the United States as the Jeffersonian Republicans gained significant influence after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

- 9. William Vans Murray (1760–1803) represented Maryland’s Fifth District in the House of Representatives during the Second Congress; he also represented Maryland’s Eighth District in the Third and Fourth sessions of Congress. After he retired from the House in 1797, President John Adams appointed him to serve as the U.S. minister to the Netherlands, and he served in this role from 1797 until 1801.

- 10. Abraham Baldwin (1754–1807) was a member of the Continental Congress, delegate to the Constitutional Convention, and signee of the Constitution. Although born in Connecticut, Baldwin practiced law in Georgia, the state he represented in the House from 1789 until 1799. Following his tenure in the House, Baldwin represented Georgia in the Senate from 1799 until 1807, when he died in office.

- 11. Baldwin was concerned that allowing the secretary of the treasury to submit a plan would set a precedent and thereby “construct” a right or practice of the secretary submitting such reports.

- 12. John Laurance (1750–1810), a member of the Federalist Party, represented New York in the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1793, then was appointed to fill the seat vacated by James Duane on the U.S. District Court for the District of New York. After two years, in 1796, Laurance resigned after being elected to the U.S. Senate. He represented New York in the Senate from 1796, until 1800, when he resigned from office.

- 13. William Findley (1741–1821), an immigrant from Ireland and a Republican, served in the Pennsylvania legislature and many terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Who Are the Best Keepers of the People’s Liberties

December 20, 1792

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.