No related resources

Introduction

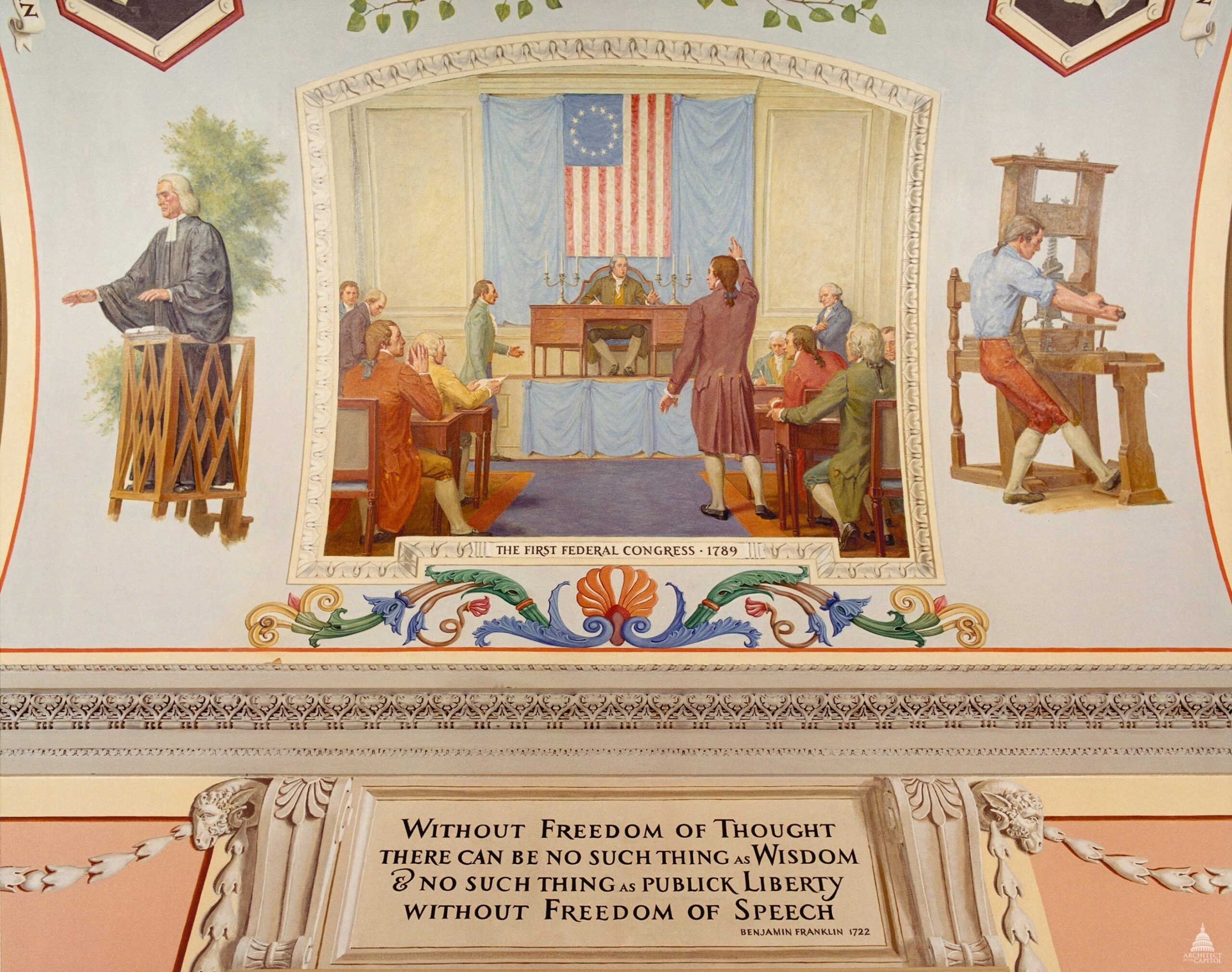

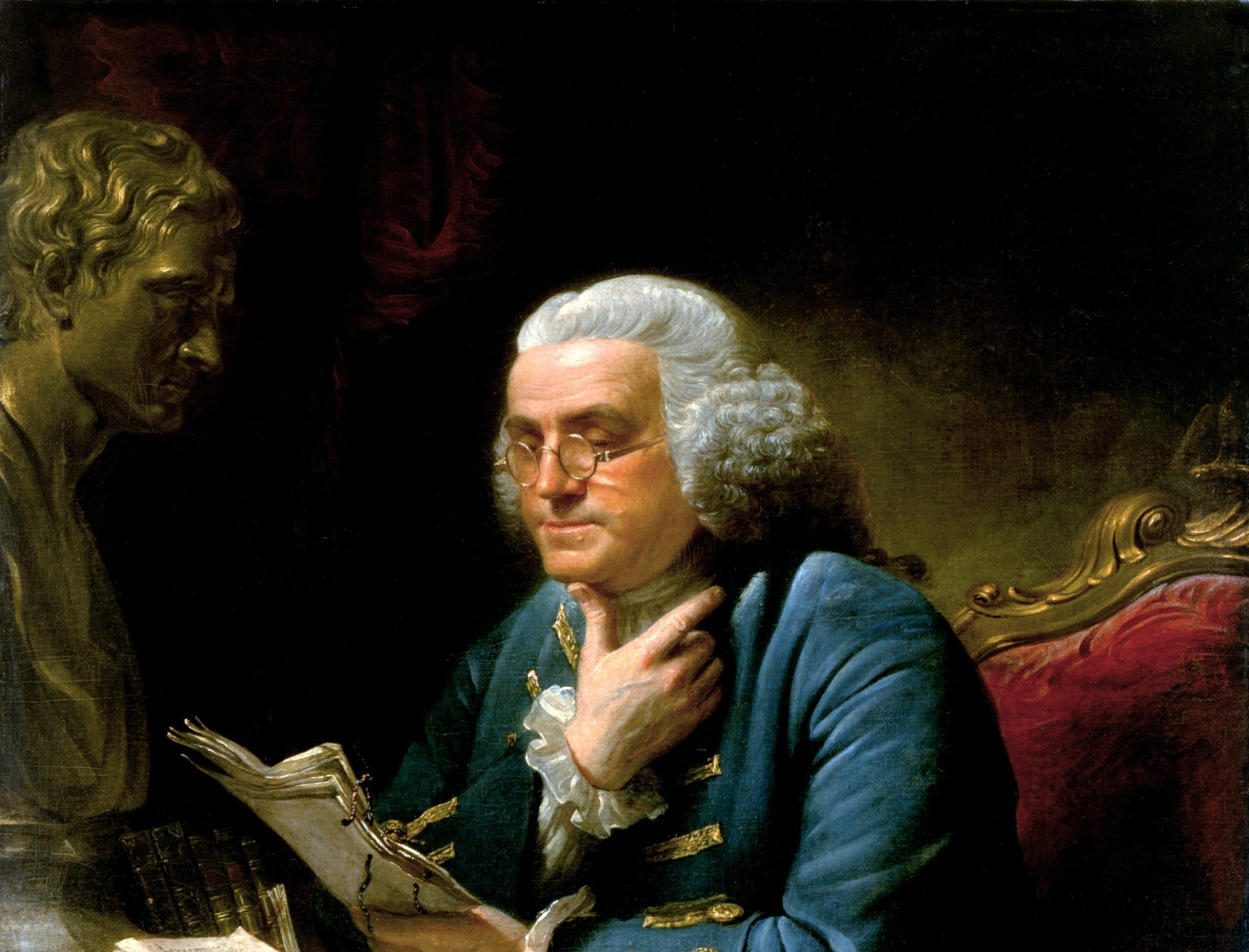

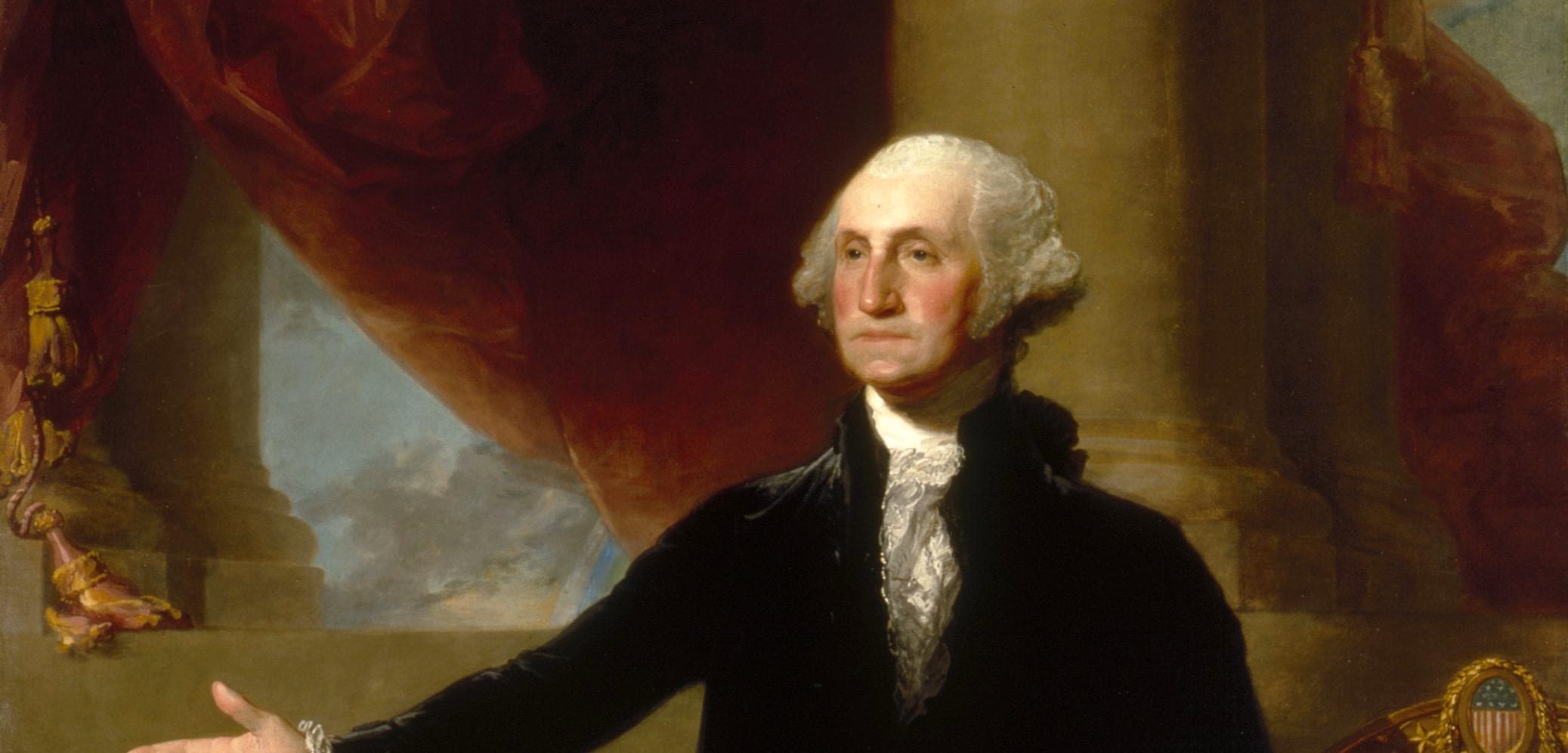

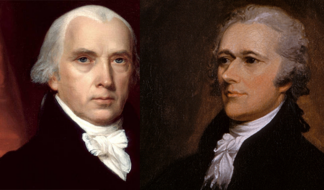

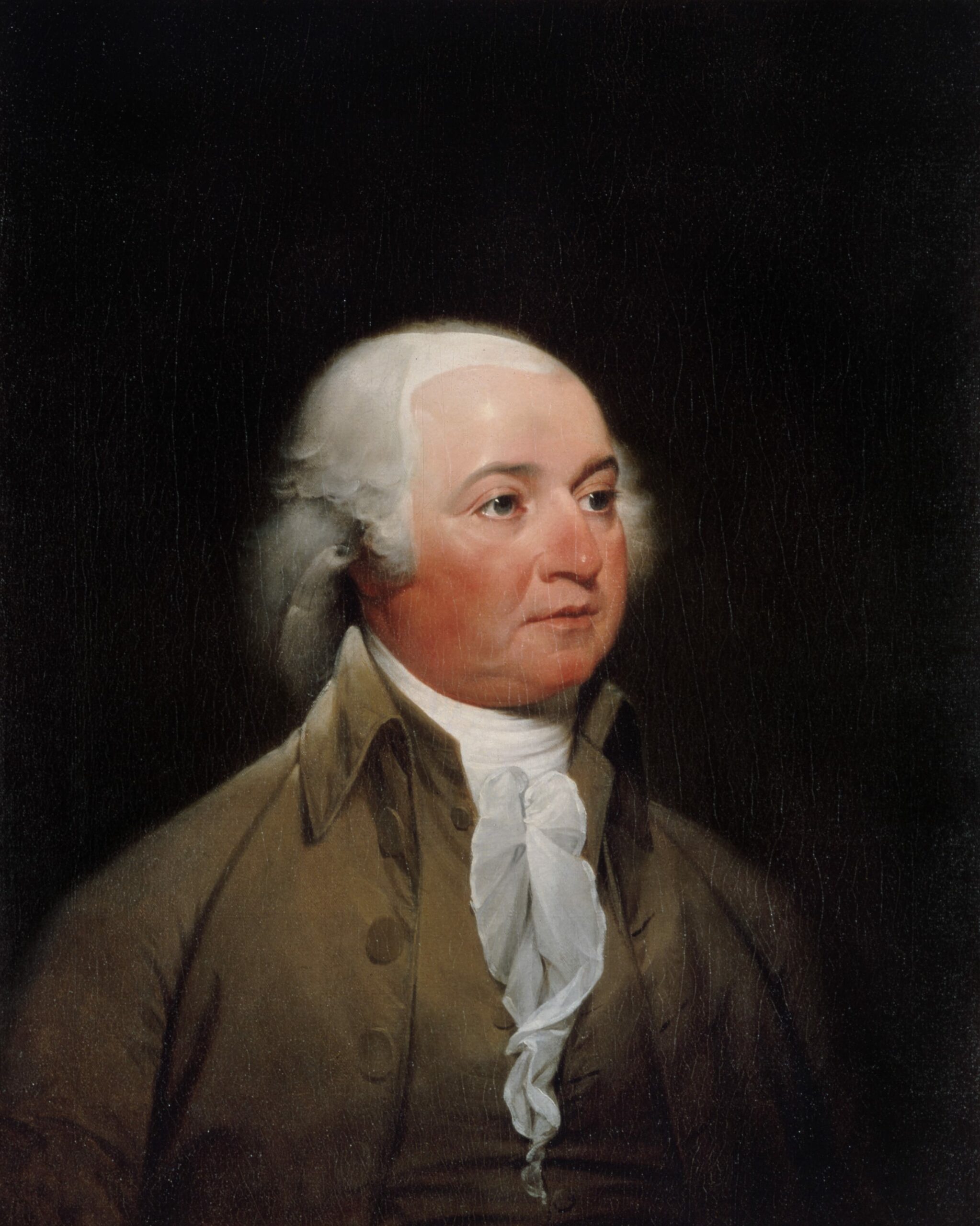

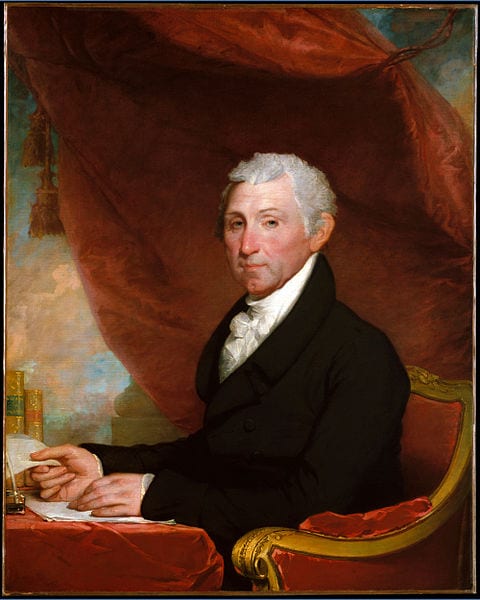

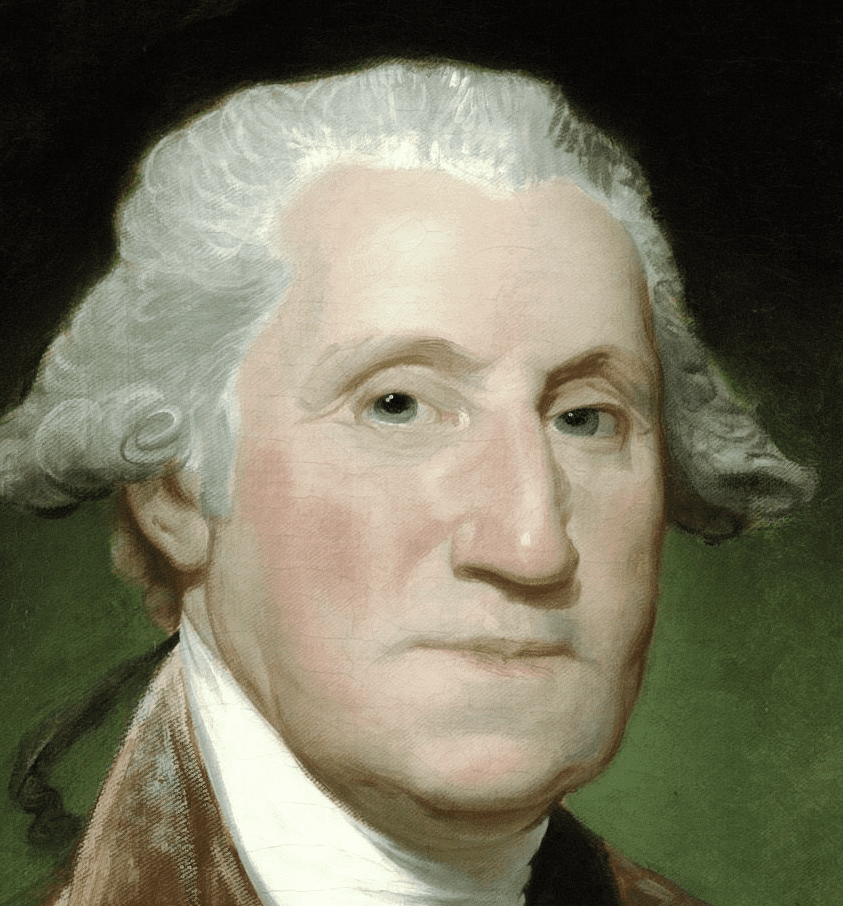

The members of the House of Representatives of the First Congress sent James Madison’s proposals to a select committee. The House debated the report of the committee between August 13 and 24, 1789. The report and these debates show that Madison, although initially successful in shaping the content of the Bill of Rights, was ultimately unsuccessful in his attempt to “interweave” the proposed alterations into the body of the original Constitution. Also, thanks to his old nemesis from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Roger Sherman, he failed to alter the Preamble of the Constitution to incorporate, expressly, the principles of the Declaration of Independence. In short, he was unsuccessful in creating a new founding that incorporated in one document the Declaration, the original Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

He was successful, however, in limiting the scope of the alterations in the Constitution to a friendly declaration of rights rather than unfriendly amendments of the structure and powers of the federal government (See The Virginia Ratifying Convention and The New York Ratifying Convention). He also persuaded the House to include what he considered to be his three most important items in a declaration of rights—conscience, press, and jury—as restrictions on both the federal and the state governments. Note the subtle changes in language concerning the two religion clauses as Madison’s proposals made their way through the debates in the House.

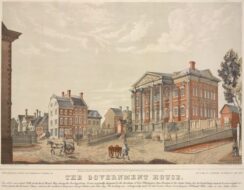

Source: Congress of the United States In the House of Representatives, Tuesday, the 27th of July: Mr. Vining, from the Committee of eleven, to whom it was referred to take the subject of amendments to the constitution of the United States, genera. (New York: Thomas Greenleaf, 1789) Library of Congress, goo.gl/roAqoH; Annals of Congress, ed. Joseph Gales, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1834), vol. I: 734–735, 742–743, 744, 746–747, 808); available online from A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Library of Congress, goo.gl/VV4HTS. See also The Essential Bill of Rights, ed. Gordon Lloyd and Margie Lloyd (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1998), 345–353.

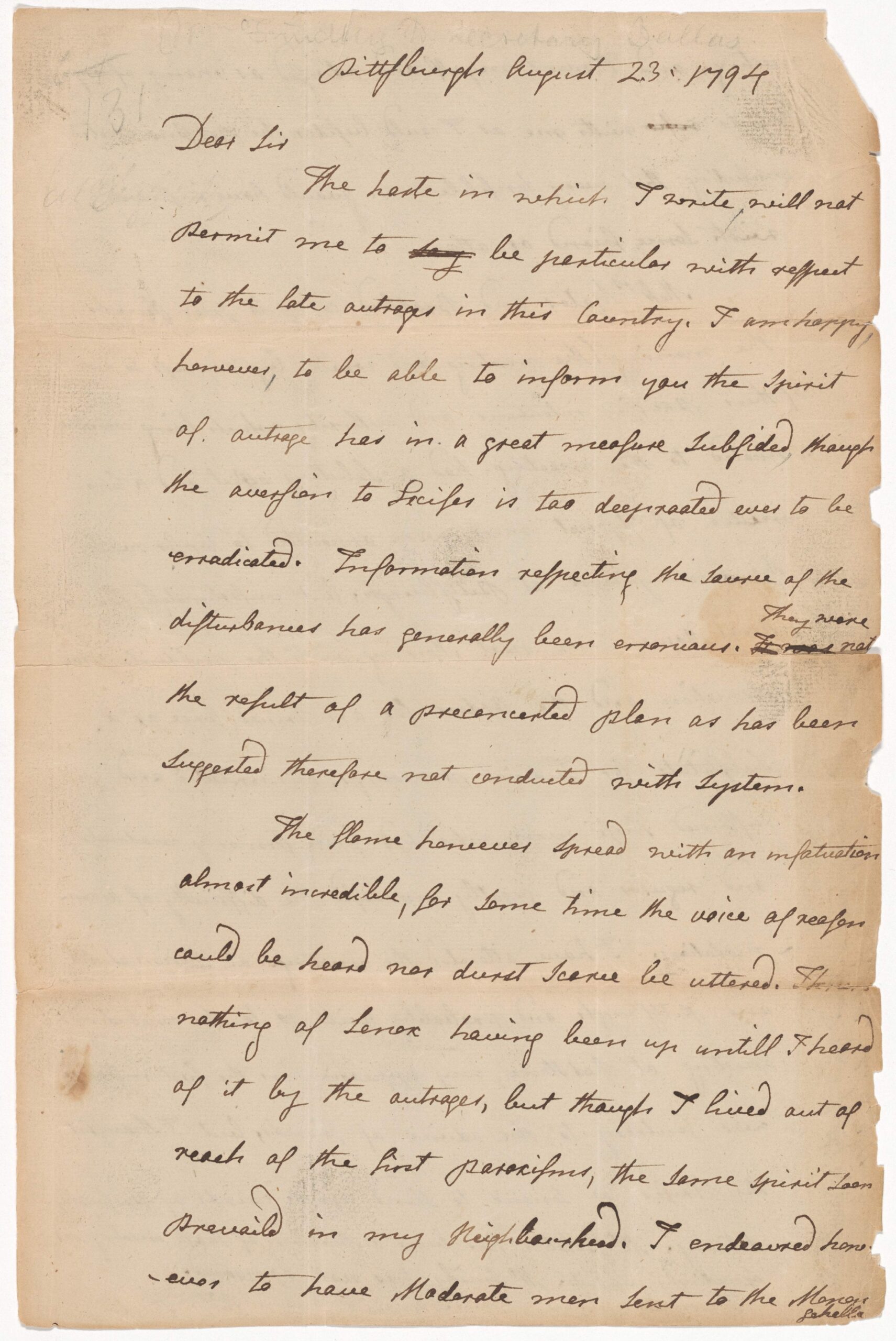

Report of the House Select Committee | July 28, 1789

Mr. VINING, from the committee of eleven, to whom it was referred to take the subject of AMENDMENTS to the CONSTITUTION of the UNITED STATES, generally into their consideration, and to report thereupon, made a report, which was read, and is as followeth:

In the introductory paragraph before the words, “We the people,” add, “government being intended for the benefit of the people, and the rightful establishment thereof being derived from their authority alone.”

ART. I, SEC. 2, PAR. 3—Strike out all between the words, “direct” and “and until such,” and instead thereof insert, “After the first enumeration there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand until the number shall amount to one hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress that the number of Representatives shall never be less than one hundred, nor more than one hundred and seventy-five, but each State shall always have at least one Representative.”

ART. I, SEC. 6—Between the words, “United States,” and “shall in all cases,” strike out “they,” and insert, “But no law varying the compensation shall take effect until an election of Representatives shall have intervened. The members.”

ART. I, SEC. 9—Between PAR. 2 and 3 insert “No religion shall be established by law, nor shall the equal rights of conscience be infringed.”

“The freedom of speech, and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good, and to apply to the government for redress of grievances, shall not be infringed.”

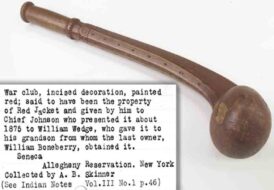

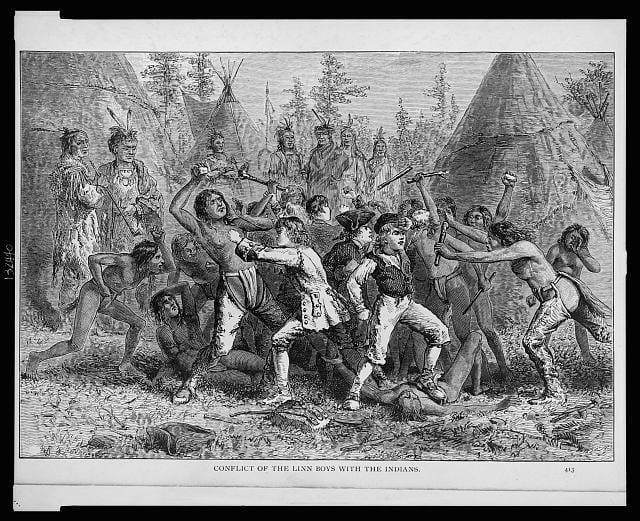

“A well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed, but no person religiously scrupulous shall be compelled to bear arms.”

“No soldier shall in time of peace be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

“No person shall be subject, except in case of impeachment, to more than one trial or one punishment for the same offence, nor shall be compelled to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.”

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted.”

“The right of the people to be secure in their person, houses, papers and effects, shall not be violated by warrants issuing, without probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and not particularly describing the places to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

“The enumeration in this Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

ART. 1, SEC. 10, between the 1st and 2d PAR. insert, “No state shall infringe the equal rights of conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of the press, nor of the right of trial by jury in criminal cases.”

ART. 3, SEC. 2, add to the 2d PAR. “But no appeal to such court shall be allowed, where the value in controversy shall not amount to one thousand dollars; nor shall any fact, triable by a jury according to the course of the common law, be otherwise re-examinable than according to the rules of common law.”

ART. 3, SEC. 2—Strike out the whole of the 3d paragraph, and insert: “In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.”

“The trial of all crimes (except in cases of impeachment, and in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger) shall be by an impartial jury of freeholders of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, the right of challenge and other accustomed requisites; and no person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment by a grand jury; but if a crime be committed in a place in the possession of an enemy, or in which an insurrection may prevail, the indictment and trial may by law be authorized in some other place within the same state; and if it be committed in a place not within a state, the indictment and trial may be at such place or places as the law may have directed.”

“In suits at common law the right of trial by jury shall be preserved.”

“Immediately after ART. 6, the following to be inserted as ART. 7:

“The powers delegated by this Constitution to the government of the United States, shall be exercised as therein appropriated, so that the Legislative shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or the Judicial; nor the Executive the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial; nor the Judicial the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive.”

“The powers not delegated by this Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively.”

ART. 7 to be made ART. 8.

House Debates Select Committee Report | August 13–24, 1789

Thursday, August 13

The House then resolved itself into a committee of the whole, Mr. BOUDINOT in the chair, and took the amendments under consideration.

The first article ran thus: “In the introductory paragraph of the Constitution, before the words ‘We the people,’ add ‘government being intended for the benefit of the people, and the rightful establishment thereof being derived from their authority alone.’

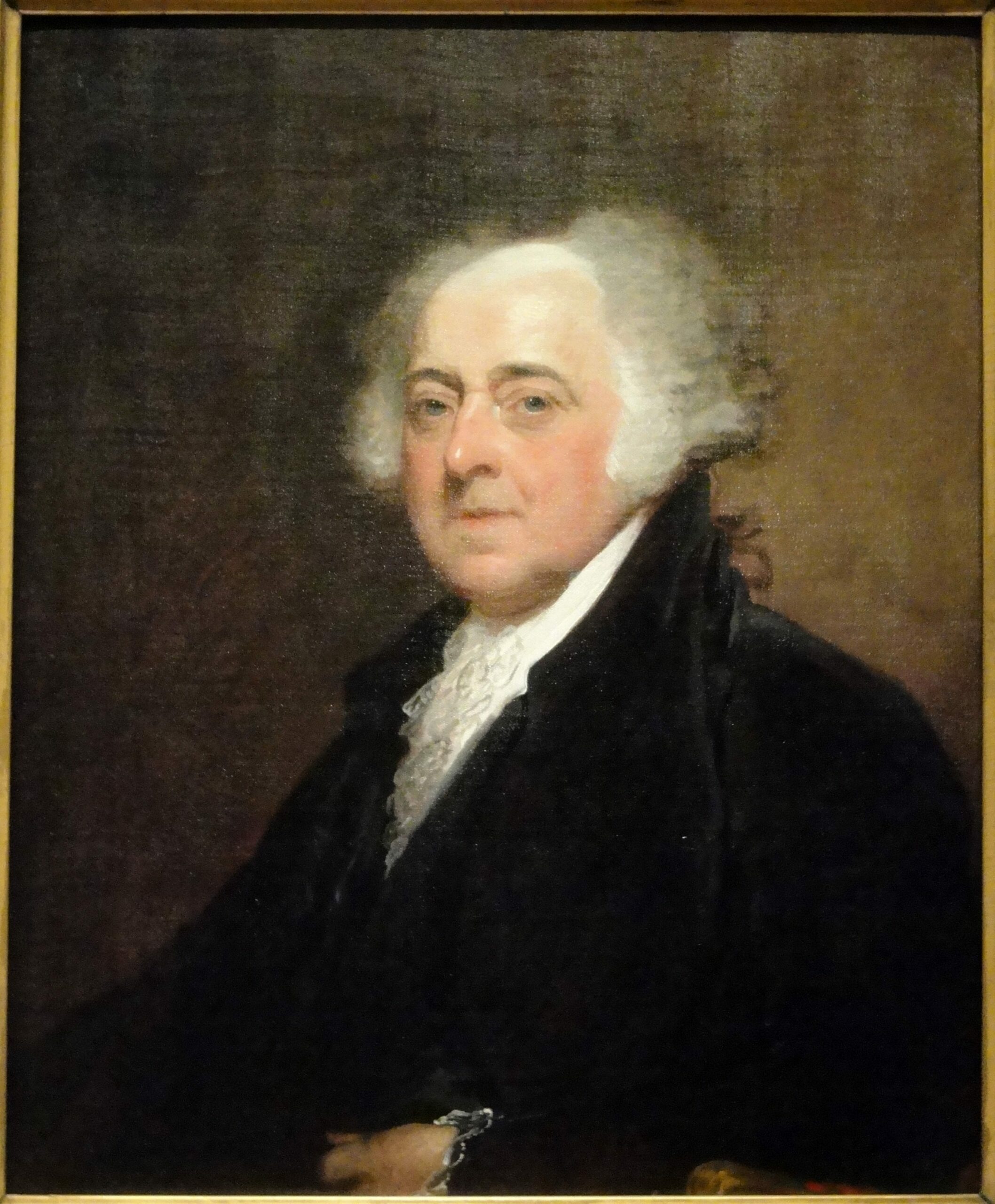

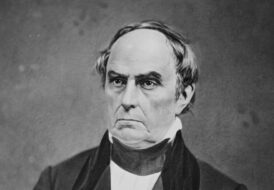

Mr. SHERMAN. I believe, Mr. Chairman, this is not the proper mode of amending the Constitution. We ought not to interweave our propositions into the work itself, because it will be destructive of the whole fabric. We might as well endeavor to mix brass, iron, and clay, as to incorporate such heterogeneous articles, the one contradictory to the other. Its absurdity will be discovered by comparing it with a law. Would any legislature endeavor to introduce into a former act a subsequent amendment, and let them stand so connected? When an alteration is made in an act, it is done by way of supplement; the latter act always repealing the former in every specified case of difference.

Besides this, sir, it is questionable whether we have the right to propose amendments in this way. The Constitution is the act of the people, and ought to remain entire. But the amendments will be the act of the state governments. Again, all the authority we possess is derived from that instrument; if we mean to destroy the whole, and establish a new Constitution, we remove the basis on which we mean to build. For these reasons, I will move to strike out that paragraph and substitute another.

The paragraph proposed was to the following effect:

Resolved, by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States in Congress assembled, That the following articles be proposed as amendments to the Constitution, and when ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures shall become valid to all intents and purposes, as part of the same.

Under this title, the amendments might come in nearly as stated in the report, only varying the phraseology so as to accommodate them to a supplementary form.

Mr. MADISON. Form, sir, is always of less importance than the substance; but on this occasion I admit that form is of some consequence, and it will be well for the House to pursue that which, upon reflection, shall appear to be the most eligible. Now it appears to me, that there is a neatness and propriety in incorporating the amendments into the Constitution itself; in that case, the system will remain uniform and entire; it will certainly be more simple when the amendments are interwoven into those parts to which they naturally belong, than it will if they consist of separate and distinct parts. We shall then be able to determine its meaning without references or comparison; whereas, if they are supplementary, its meaning can only be ascertained by a comparison of the two instruments, which will be a very considerable embarrassment. It will be difficult to ascertain to what parts of the instrument the amendments particularly refer; they will create unfavorable comparisons; whereas, if they are placed upon the footing here proposed, they will stand upon as good foundation as the original work. Nor is it so uncommon a thing as gentlemen suppose; systematic men frequently take up the whole law, and, with its amendments and alterations, reduce it into one act. I am not, however, very solicitous about the form, provided the business is but well completed. . . .

Mr. SHERMAN. If I had looked upon this question as a mere matter of form, I should not have brought it forward, or troubled the committee with such a lengthy discussion. But, sir, I contend that amendments made in the way proposed by the committee are void. No gentleman ever knew an addition and alteration introduced into an existing law, and that any part of such law was left in force; but if it was improved or altered by a supplemental act, the original retained all its validity and importance, in every case where the two were not incompatible. But if these observations alone should be thought insufficient to support my motion, I would desire gentlemen to consider the authorities upon which the two Constitutions are to stand. The original was established by the people at large, by conventions chosen by them for the express purpose. The preamble to the Constitution declares the act; but will it be a truth in ratifying the next Constitution, which is to be done perhaps by the State Legislatures, and not conventions chosen for the purpose? Will gentlemen say it is “We the people” in this case? Certainly they cannot; for, by the present Constitution, we, nor all the legislatures in the Union together, do not possess the power of repealing it. All that is granted us by the 5th article is, that whenever we shall think it necessary, we may propose amendments to the Constitution; not that we may propose to repeal the old, and substitute a new one.

Gentlemen say, it would be convenient to have it in one instrument, that people might see the whole at once; for my part, I view no difficulty on this point. The amendments reported are a declaration of rights; the people are secure in them, whether we declare them or not; the last amendment but one provides that the three branches of government shall each exercise its own rights. This is well secured already; and, in short, I do not see that they lessen the force of any article in the Constitution; if so, there can be little more difficulty in comprehending them whether they are combined in one, or stand distinct instruments. . . .

Mr. SHERMAN. The gentlemen who oppose the motion say we contend for matter of form; they think it nothing more. Now we say we contend for substance, and therefore cannot agree to amendments in this way. If they are so desirous of having the business completed, they had better sacrifice what they consider but a matter of indifference to gentlemen, to go more unanimously along with them in altering the Constitution.

The question on Mr. SHERMAN’S motion was now put and lost. . . .

Friday, August 14

. . . Mr. MADISON. If it be a truth, and so self-evident that it cannot be denied; if it be recognized, as is the fact in many of the state constitutions; and if it be desired by three important states to be added to this; I think they must collectively offer a strong inducement to the mind desirous of promoting harmony to acquiesce with the report; at least some strong arguments should be brought forward to show the reason why it is improper.

My worthy colleague says the original expression is neat and simple; that loading it with more words may destroy the beauty of the sentence; and others say it is unnecessary, as the paragraph is complete without it. Be it so in their opinion; yet still it appears important in the estimation of three States that this solemn truth should be inserted in the Constitution. For my part, sir, I do not think the association of ideas anywise unnatural; it reads very well in this place; so much so, that I think gentlemen, who admit it should come in somewhere else, will be puzzled to find a better place.

Mr. SHERMAN thought they ought not to come in this place. The people of the United States have given their reasons for doing a certain act. Here we propose to come in and give them a right to do what they did on motives which appeared to them sufficient to warrant their determination; to let them know that they had a right to exercise a natural and inherent privilege, which they have asserted in a solemn ordination and establishment of the Constitution.

Now, if this right is indefeasible, and the people have recognized it in practice, the truth is better asserted than it can be by any words whatever. The words “We the people,” in the original Constitution, are as copious and expressive as possible; any addition will only drag out the sentence without illuminating it; for these reasons it may be hoped the committee will reject the proposed amendment.

The question on the first paragraph of the report was put and carried in the affirmative, twenty-seven to twenty-three. . . .

Wednesday, August 19

. . . Mr. SHERMAN renewed his motion for adding the amendments to the Constitution by way of supplement.

Hereupon, ensued a debate similar to what took place in the Committee of the Whole, [see Thursday, August 13, above] but, on the question, Mr. SHERMAN’S motion was carried by two-thirds of the House; in consequence it was agreed to.

The first proposition of amendment [see Friday, August 14, above] was rejected, because two-thirds of the members present did not support it. . . .

[Editor’s Note. The House, as the last order of business on Saturday, August 22, directed Representatives Benson, Sherman, and Sedgwick “to arrange” the agreed upon amendments “and make a report thereof.”]

Monday, August 24

Mr. BENSON, from the committee appointed for the purpose, reported an arrangement of the articles of amendment to the Constitution of the United States, as agreed to by the House on Friday last. . . .

House Approves Seventeen Amendments | August 24, 1789

ARTICLE THE FIRST.

After the first enumeration, required by the first Article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.

ARTICLE THE SECOND.

No law varying the compensation to the members of Congress, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.

ARTICLE THE THIRD.

Congress shall make no law establishing religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, nor shall the rights of conscience be infringed.

ARTICLE THE FOURTH.

The freedom of speech, and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and consult for their common good, and to apply to the government for a redress of grievances, shall not be infringed.

ARTICLE THE FIFTH.

A well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.

ARTICLE THE SIXTH.

No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

ARTICLE THE SEVENTH.

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

ARTICLE THE EIGHTH.

No person shall be subject, except in case of impeachment, to more than one trial, or one punishment for the same offence, nor shall be compelled in any criminal case, to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.

ARTICLE THE NINTH.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

ARTICLE THE TENTH.

The trial of all crimes (except in cases of impeachment, and in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia when in actual service in time of war or public danger) shall be by an impartial jury of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, the right of challenge, and other accustomed requisites; and no person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherways infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment by a grand jury; but if a crime be committed in a place in the possession of an enemy, or in which an insurrection may prevail, the indictment and trial may by law be authorized in some other place within the same state.

ARTICLE THE ELEVENTH.

No appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, shall be allowed, where the value in controversy shall not amount to one thousand dollars, nor shall any fact, triable by a jury according to the course of the common law, be otherwise re-examinable, than according to the rules of common law.

ARTICLE THE TWELFTH.

In suits at common law, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved.

ARTICLE THE THIRTEENTH.

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

ARTICLE THE FOURTEENTH.

No state shall infringe the right of trial by jury in criminal cases, nor the rights of conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of the press.

ARTICLE THE FIFTEENTH.

The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

ARTICLE THE SIXTEENTH.

The powers delegated by the Constitution to the government of the United States, shall be exercised as therein appropriated, so that the Legislative shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial; nor the Executive the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial; nor the Judicial the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive.

ARTICLE THE SEVENTEENTH.

The powers not delegated by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it, to the states, are reserved to the states respectively.

House Debates Select Committee Report

August 13, 1789

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.