No related resources

Introduction

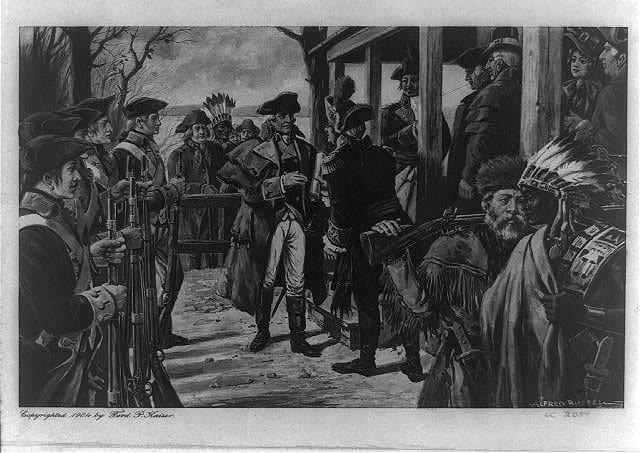

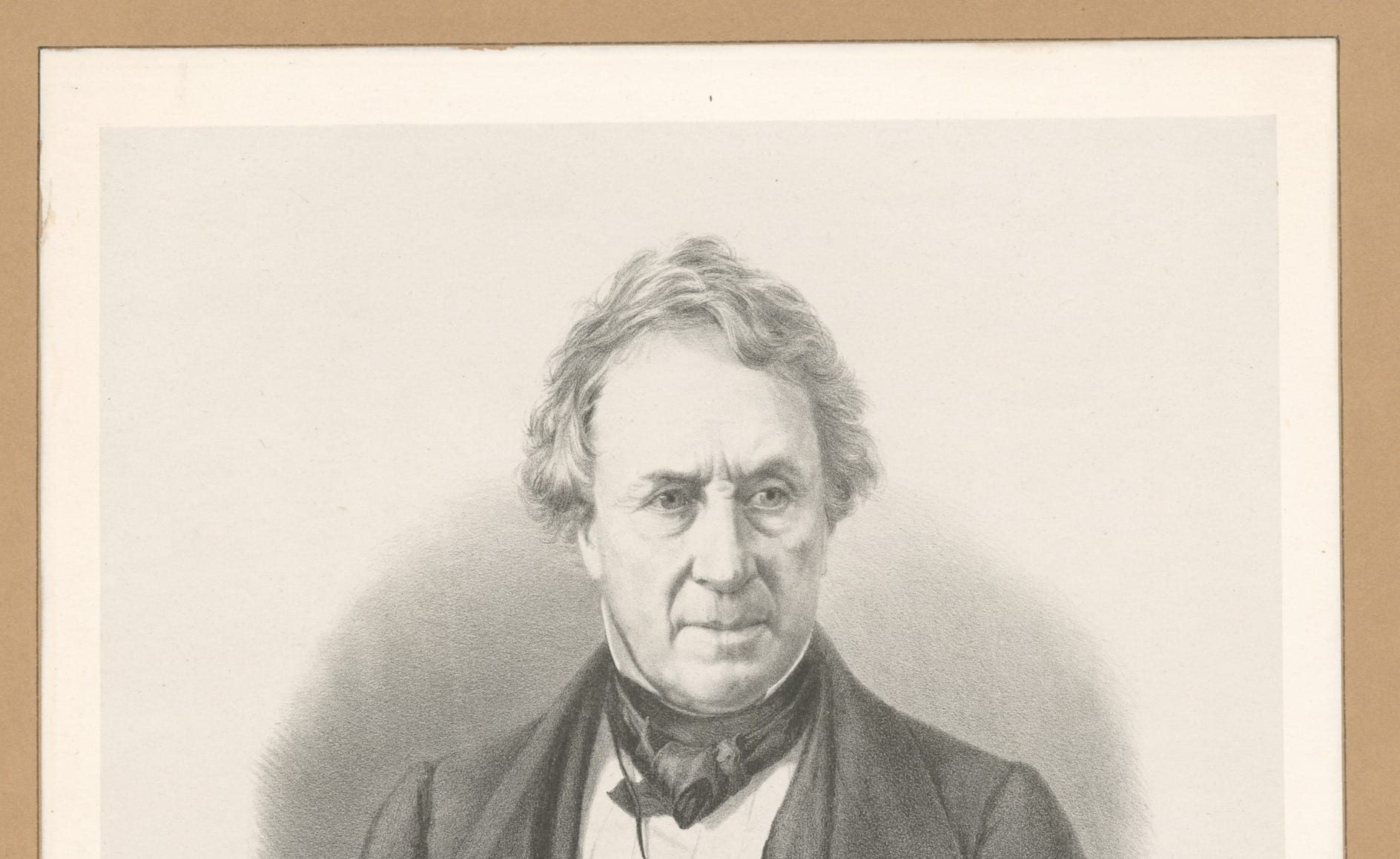

Thayendanegea, or Joseph Brant (1743–1807), a Mohawk, was possibly the foremost Indian warrior and diplomat of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Like Samson Occom he was educated by Eleazer Wheelock. Although not born into hereditary leadership, because of his intellect, capabilities, charisma, and the patronage of Sir William Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies, he rose to be a war chief.

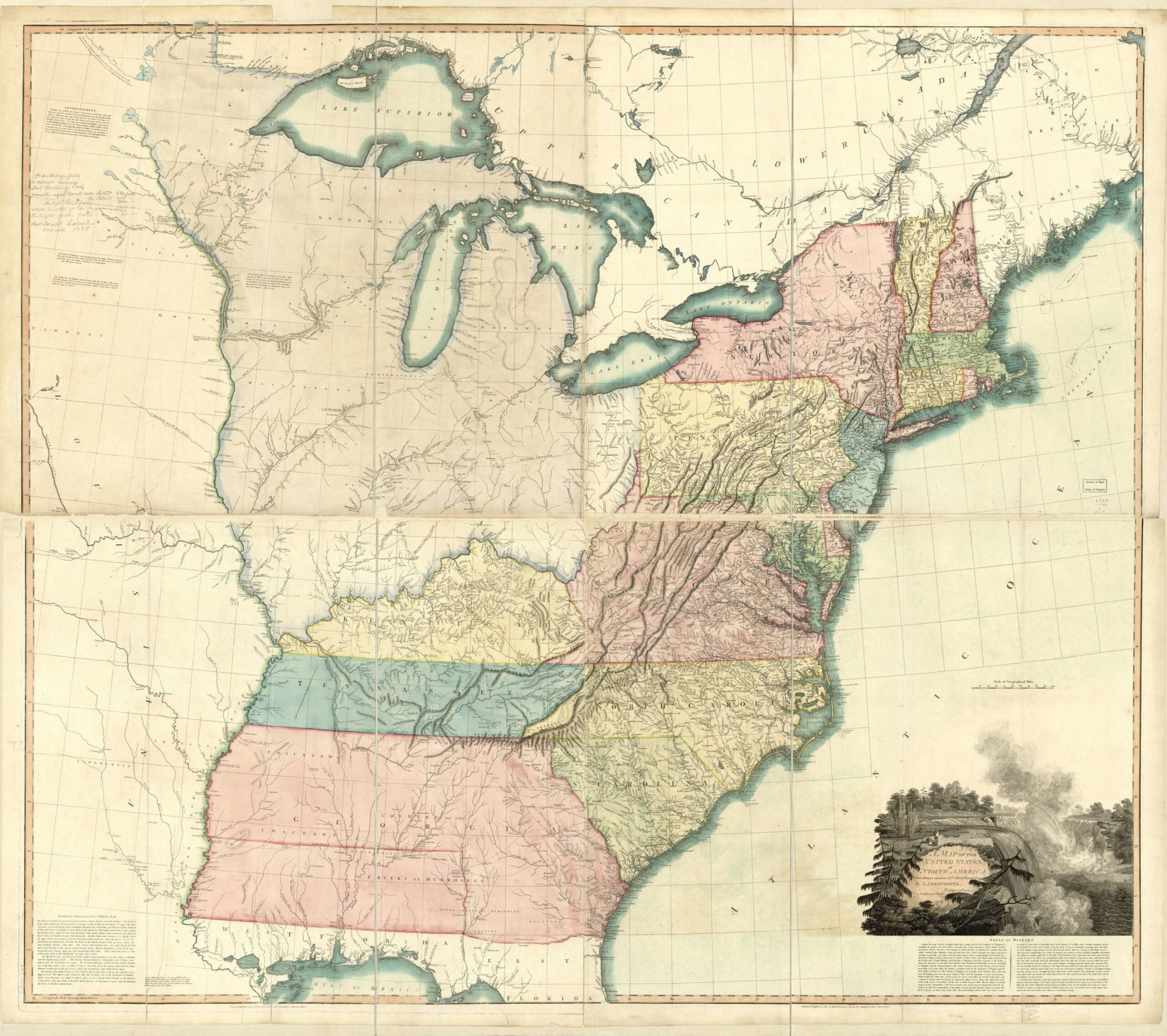

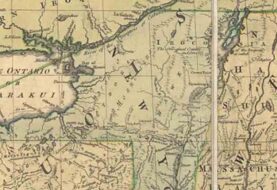

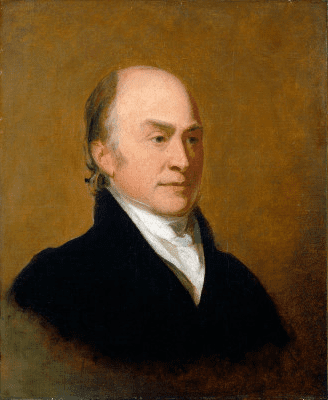

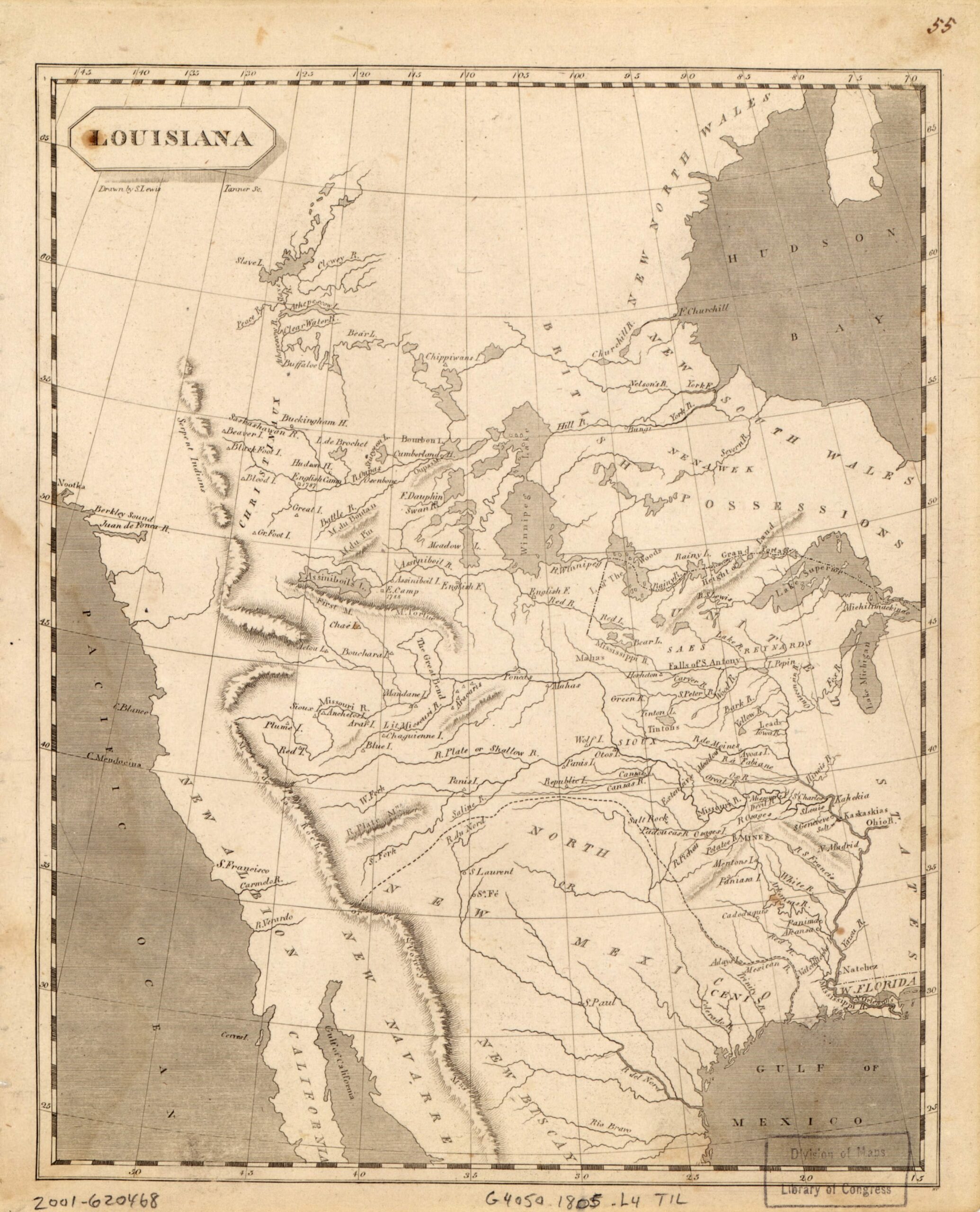

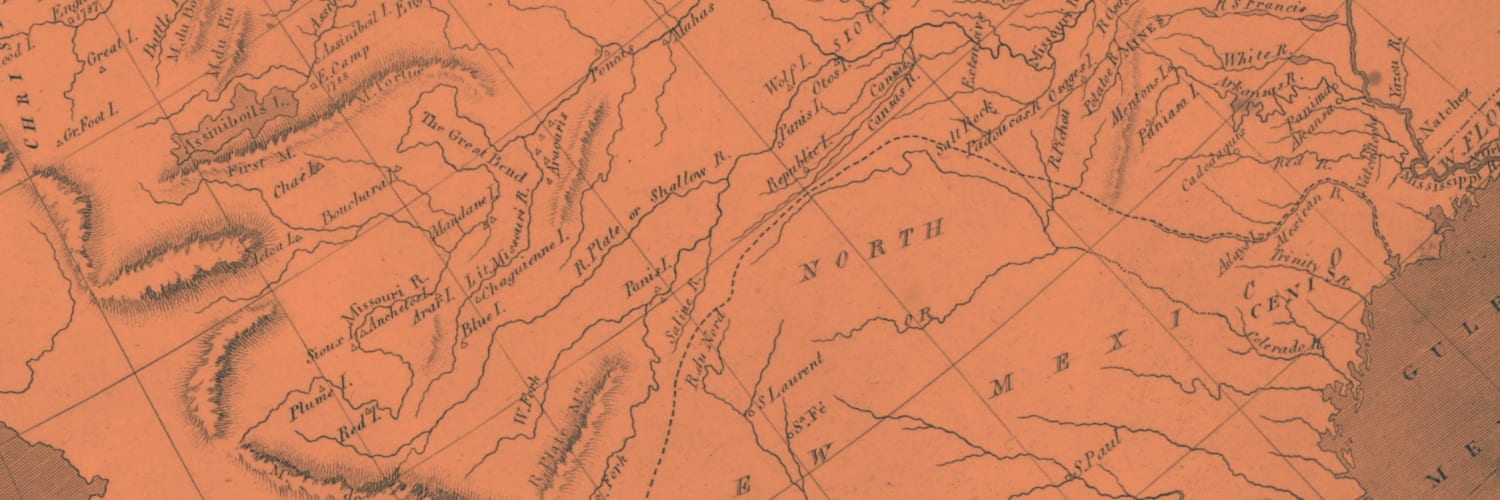

Because the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) had a “covenant chain” (existing treaties) with Great Britain, Brant fought for the British during the American Revolution. Following the war, he helped negotiate the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, meant to secure peace between the United States and the Haudenosaunee, but the Haudenosaunee Confederacy refused to ratify it. He twice traveled to England and met many powerful and prominent men, including King George III, Edmund Burke, James Boswell, Gilbert Stuart, and the future King George IV. He was involved in the initial stages of the Northwest Confederacy of Indians in the Great Lakes region.

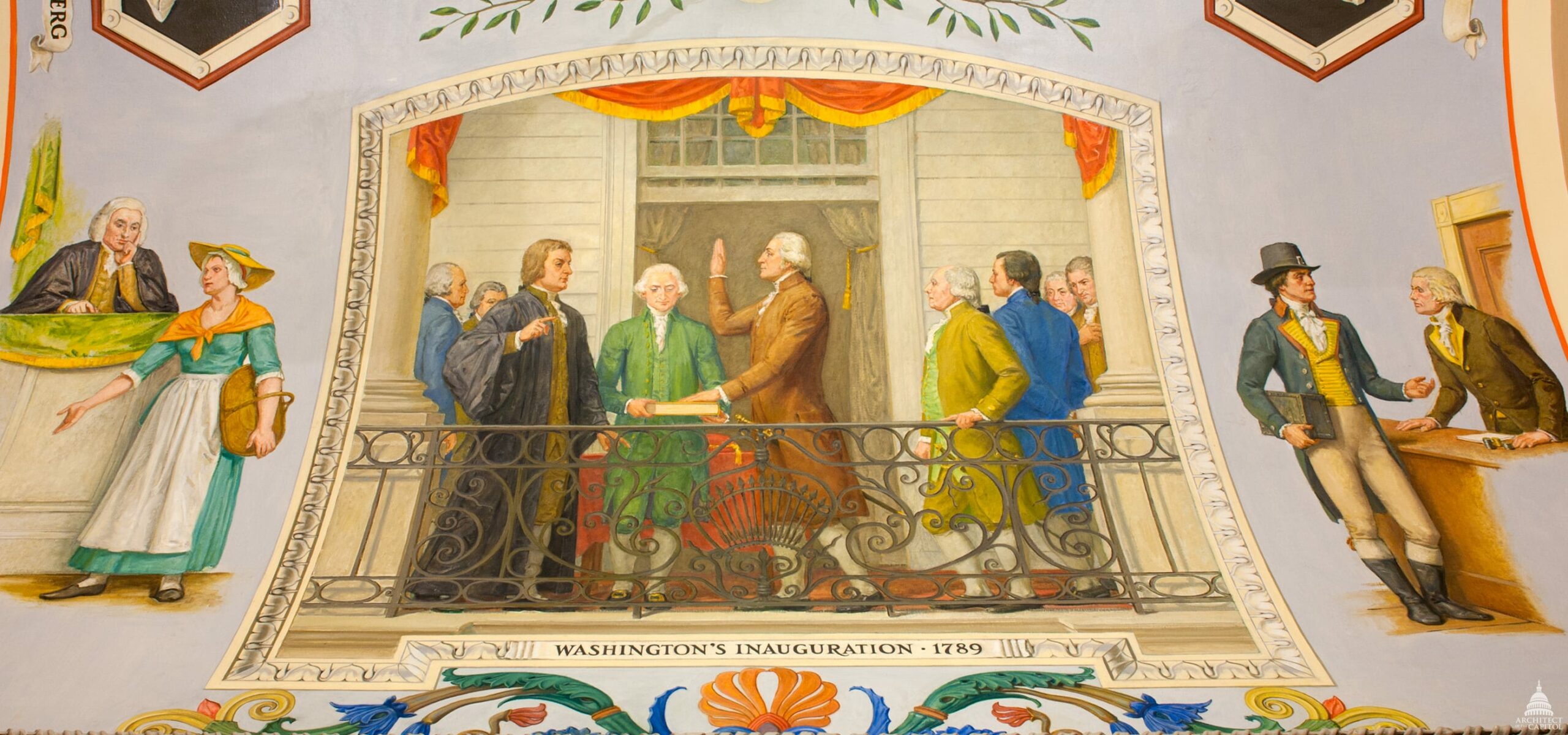

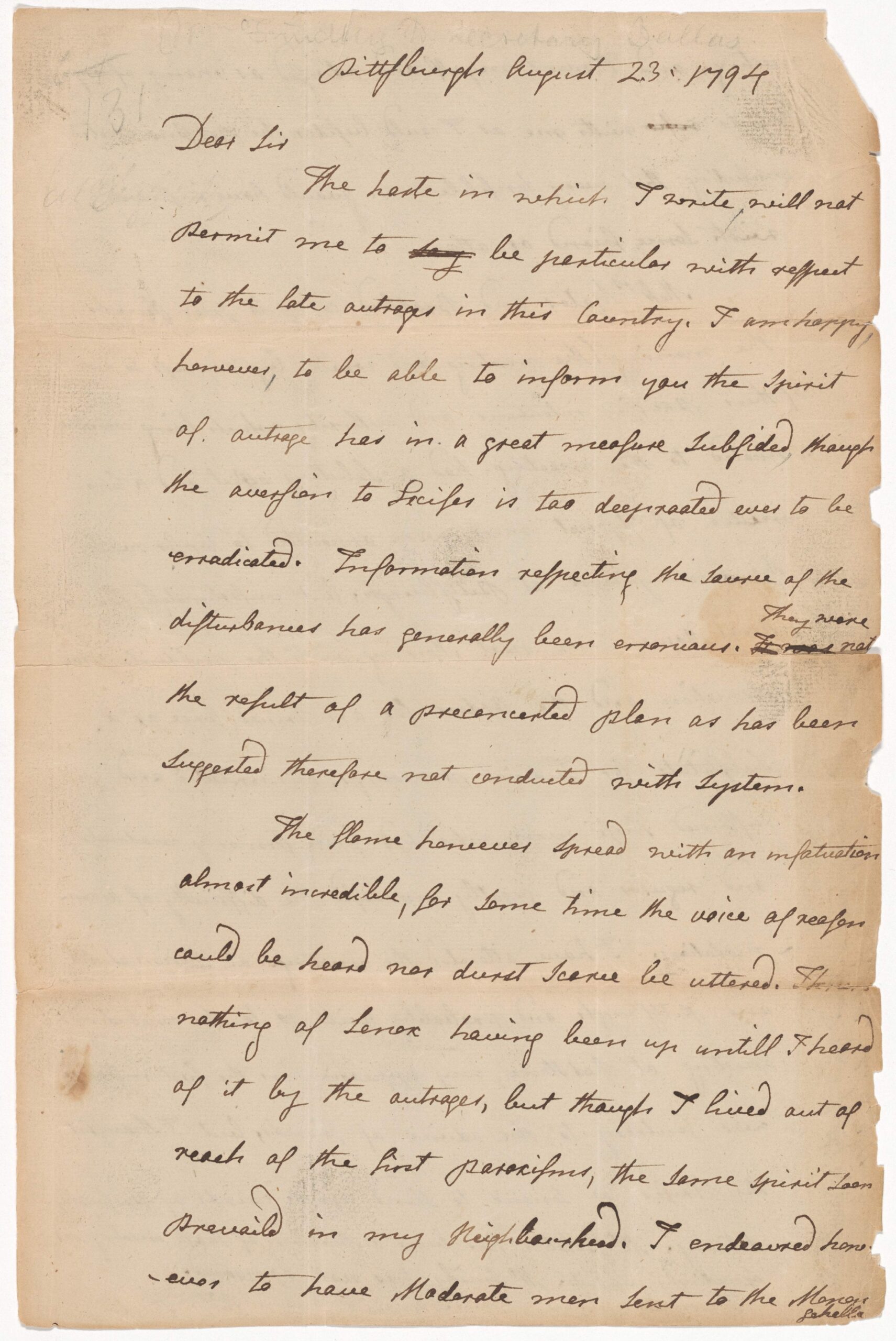

This speech was delivered at a meeting of the council of the Haudenosaunee at Buffalo Creek in 1794. The British, however, sabotaged any hope of a successful treaty between the Indians and the United States by intimating that war was imminent with the Americans and suggesting the Indians would have Britain’s support in securing their lands.

Historical Collections and Researches Made by the Pioneer and Historical Society of the State of Michigan, vol. 12 (Lansing: Thorp and Godfrey, 1888), 112-115, ttps://www.google.com/books/edition/Michigan_Historical_Collections/paYfAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Reply of the Six Nations of Indians assembled in council at Buffalo Creek the 21st April 1794, to a speech from General Knox, Secretary of War for the United States, delivered by General Chapin on the 10th February last, as interpreted by Jasper Parish, one of the interpreters for the United States. Captain Brant then rose and spoke.

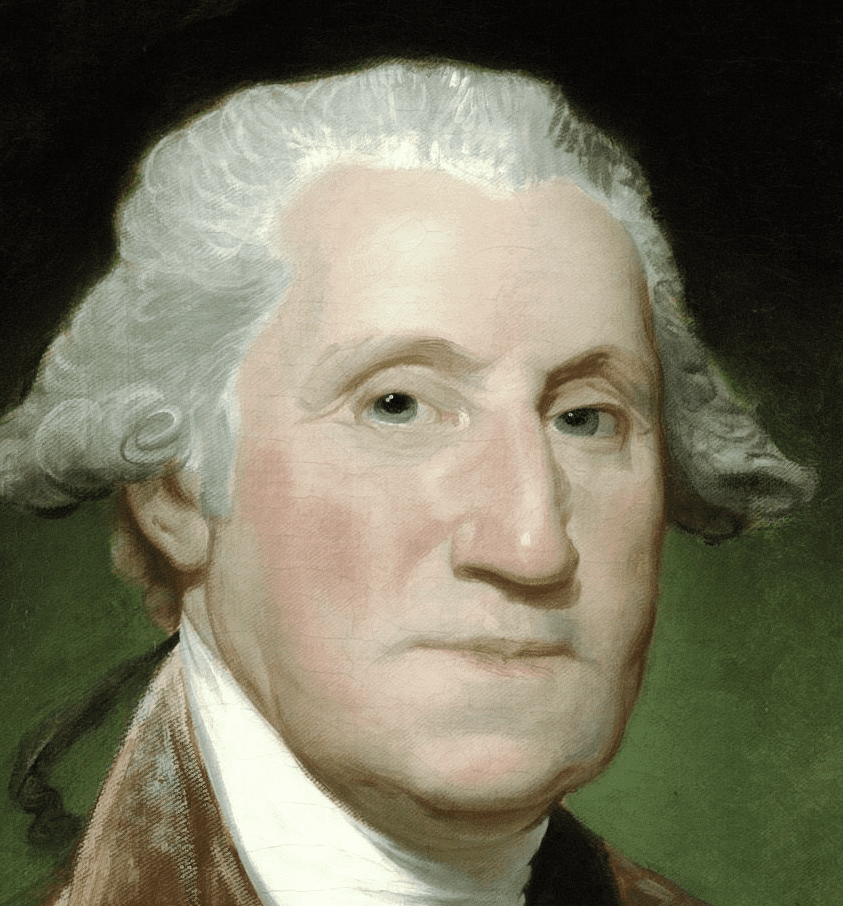

Brothers: You, of the United States, listen to what we are going to say to you; you, likewise, the King.1

Brothers: We are very happy to see you, Colonel Butler and General Chapin, sitting side by side, with the intent of hearing what we have to say. We wish to do no business but what is done open and above-board.

Brother: You, of the United States, make your mind easy, on account of the long time your president’s speech has been under our consideration; when we received it, we told you it was a business of importance and required some time to be considered of.

Brother: The answer you have brought us is not according to what we expected, which was the reason for our long delay; the business would have been done with expedition, had the United States agreed to our proposals. We would then have collected our associates, and repaired to Venango,2 the place you proposed for meeting us.

Brother: It is not now in our power to accept your invitation; provided we were to go, you would conduct the business as you might think proper; this has been the case at all the treaties held, from time to time, by your commissioners.

Brother: At the first treaty, after the conclusion of the war between you and Great Britain, at Fort Stanwix,3 your commissioners conducted the business as it to them seemed best; they pointed out a line of division, and then confirmed it; after this, they held out that our country was ceded to them by the king; this confused the chiefs who attended there, and prevented them from making any reply to the contrary; still holding out, if we did not consent to it, their warriors were at their back, and that we would get no further protection from Great Britain. This has ever been held out to us, by the commissioners from Congress; at all the treaties held with us since the peace, at Fort McIntosh, at Rocky River,4 and every other meeting held, the idea was still the same.

Brother: This has been the case from time to time. Peace has not taken place, because you have held up these ideas, owing to which much mischief has been done to the southward.

Brother: We, the Six Nations, have been exerting ourselves to keep peace since the conclusion of the war; we think it would be best for both parties; we advised the confederate nations to request a meeting, about halfway between us and the United States, in order that such steps might be taken as would bring about a peace; this request was made, and Congress appointed commissioners to meet us at Muskingum,5 which we agreed to, a boundary line was then proposed by us, and refused by Governor St. Clair, one of your commissioners. The Wyandots, a few Delawares, and some others met the commissioners, though not authorized, and confirmed the lines of what was not their property, but a common to all nations.

Brothers: The idea we all held out at our council, at Lower Sandusky,6 held for the purpose of forming our confederacy, and to adopt measures that would be for the general welfare of our Indian nations, or people of our color; owing to those steps taken by us, the United States held out, that when we went to the westward to transact our private business, that we went with an intention of taking an active part in the troubles subsisting between them and our western brethren; this never has been the case. We have ever wished for the friendship of the United States.

Brother: We think you must be fully convinced, from our perseverance last summer, as your commissioners saw, that we were anxious for a peace between us. The exertions that we, the Six Nations, have made toward the accomplishing this desirable end, is the cause of the western nations being somewhat dubious as to our sincerity. After we knew their doubts, we still persevered; and, last fall, we pointed out methods to be taken, and sent them, by you, to Congress; this we certainly expected would have proved satisfactory to the United States; in that case we should have more than ever exerted ourselves, in order that the offers we made should be confirmed by our confederacy, and by them strictly adhered to.

Brother: Our proposals have not met with the success from Congress that we expected; this still leaves us in a similar situation to what we were when we first entered on the business.

Brother: You must recollect the number of chiefs who have, at divers times, waited on Congress; they have pointed out the means to be taken, and held out the same language, uniformly, at one time as another; that was, if you would withdraw your claim to the boundary line, and lands within the line, as offered by us; had this been done, peace would have taken place; and, unless this still be done, we see no other method of accomplishing it.

Brother: We have borne everything patiently for this long time past; we have done everything we could consistently do with the welfare of our nations in general—notwithstanding the many advantages that have been taken of us, by individuals making purchases from us, the Six Nations, whose fraudulent conduct toward us Congress never has taken notice of, nor in any wise seen us rectified, nor made our minds easy. This is the case to the present day; our patience is now entirely worn out; you see the difficulties we labor under, so that we cannot at present rise from our seats and attend your council at Venango, agreeable to your invitation. The boundary line we pointed out, we think is a just one, although the United States claim lands west of that line; the trifle that has been paid by the United States can be no object in comparison to what a peace would be.

Brother: We are of the same opinion with the people of the United States; you consider yourselves as independent people; we, as the original inhabitants of this country, and sovereigns of the soil, look upon ourselves as equally independent, and free as any other nation or nations. This country was given to us by the Great Spirit above; we wish to enjoy it, and have our passage along the lake, within the line we have pointed out.

Brother: The great exertions we have made, for this number of years, to accomplish a peace, and have not been able to obtain it; our patience, as we have already observed, is exhausted, and we are discouraged from persevering any longer. We, therefore, throw ourselves under the protection of the Great Spirit above, who, we hope, will order all things for the best. We have told you our patience is worn out; but not so far, but that we wish for peace, and, whenever we hear that pleasing sound, we shall pay attention to it.

- 1. Possibly a reference to George Washington.

- 2. North of present-day Pittsburgh.

- 3. Near present-day Rome, New York. Several treaties between the Indians and the British and then the United States were signed at Fort Stanwix.

- 4. A short distance northwest from present-day Pittsburgh.

- 5. In the eastern part of Ohio.

- 6. On Lake Erie in Ohio.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.