Native Americans

The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress. . . .

Northwest Ordinance (1787)

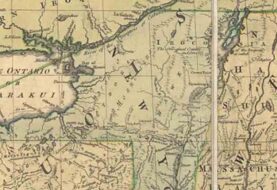

Settlers in North America, be they the Vikings, the French, or the English, followed the same pattern with regard to the Indigenous peoples they encountered: first cooperation, then conflict. Even the Spanish, whose reputation for unrelenting cruelty preceded them, were initially treated with hospitality by the Pueblos in New Mexico.

The young American Republic promised fair dealing with the original sovereigns of the land it occupied. It professed to have a trust obligation toward them. Despite periodic attempts to live up to these responsibilities, its efforts were hampered by fundamental misunderstandings of Native cultures and a paternalistic attitude that non-Indians knew what was best for Native Americans. The old pattern was replicated. This volume documents a repeated cycle of conflict and resistance. There were, however, non-Natives who saw things clearly. William Tecumseh Sherman, who prosecuted the Indian Wars in the West with the same “hard-war” methods he employed during the Civil War, was among those who were gimlet-eyed about U.S. Indian affairs. His mordant observations dot this book. (The irony in Sherman’s middle name is obvious; his father was an admirer of the great Shawnee leader.)

Dispossession and loss are major themes in this volume. At the time Columbus arrived, best estimates are that there were between twelve and fifteen million Indigenous persons in the territory that is today the United States. This population reached its nadir in 1900, when the U.S. Census recorded just 237,000 American Indians. This tremendous population loss was not so much due to cruel treatment or warfare—though both these occurred—but to a dramatic demographic crash from “virgin soil plagues”—diseases Europeans brought with them to which the Native population had no natural immunities. The biggest killer was smallpox, but the list also includes measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, chicken pox, and influenza.

This book seeks to cover almost five hundred years of American Indian history from Jonas Michaëlius’ letter in 1628 to the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which ruled that much of that state remained Indian land or reservations because of treaties signed between Indian tribes and the U.S. government. From the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to the present day, government policy has constrained Native life. Yet despite these actions, Natives have always sought to live their lives on their own terms and to maintain the sovereignty of tribes as nations-within-a-nation, separate sovereigns in the U.S. federal system. For its part, federal policy has always vacillated between wanting to “civilize” and assimilate Indians and encouraging self-government and self-determination (See Special Message on Indian Affairs).

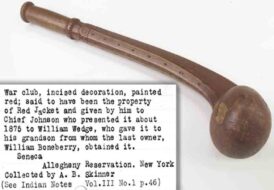

Conflict and warfare are major themes herein as well, from King Philip’s War in 1675 to the last massacre of Indians in 1911 (See Survivor Returns to Site of Last Indian Massacre). Aggressive assimilation attempts through education (“education for extinction”) is a thread from the earliest colonization (See Letter to Adrian Smoutius) through boarding schools modeled on Richard Henry Pratt’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School (See The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites). Another thread, however, is Native resistance and protest as manifested in the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969 (See Alcatraz Proclamation) and the Standing Rock Sioux’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2015 and 2016 (See Resolution Regarding Dakota Access Pipeline). Traditional Native cultures are religiously based, and religion has played a vital role in Native resistance, especially “raising-up” movements from Pontiac’s Rebellion and Tecumseh’s alliance (See Speech of Tenskwatawa and Address to the Osage) to the Ghost Dance of 1889–1890 (See Letter Regarding the Ghost Dance Doctrine and Testimony on Wounded Knee).

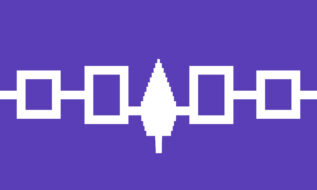

I have sought to give pride of place to Indigenous voices (although we must remember that many Native speeches were transcribed by whites). I did not want a dry assemblage of laws, legal decisions, and treaties. Though much of Indian existence has been constrained by such documents, they often do not convey the meaning and importance of events. (Legal Status of Indians offers an annotated list of some of the most important documents bearing on the legal status of Indians.) While covering the Indian Wars from King Philip’s War to the last Indian massacre in 1911, resistance to violent assimilationist policies from Christian evangelization (See “The Indians: The Ten Lost Tribes”), to boarding schools, to Termination and Relocation, and the radical activism of the 1960s and 1970s, I have tried to include surprising documents, such as the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s declaration of war in 1942, that are not the “usual suspects” often anthologized. Though it includes only forty-six documents, I believe this volume will give both teachers and students plenty to chew on.

American Indians and their ancestors have thousands of years of history on this continent. They have been part of the American story before day one—that is, before the coming of Europeans. It is often glibly said that these first American were not U.S. citizens until 1924. The Indian Citizenship Act of that year, however, was merely a “clean-up” measure covering only roughly the third of Natives who were not yet citizens. American Indians remain today a vital part of the story of the United States, as they always will be.

Note on terms: Many people assume that “Native American” is a more polite and preferred term to “American Indian.” This, however, is not the case. The former, which did not even exist until after World War II, grew out of the urban Native experience that resulted from the federal policy of Termination and Relocation (See House Concurrent Resolution 108 and Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy ). It is therefore incorrect to refer to any before that time as Native Americans. “American Indian” is an older, more rural, more reservation-based term still in use today. In the last fifteen years, an uppercase “Indigenous” has gained currency. Sometimes, simply “Native” is employed. I use all these terms interchangeably as seems appropriate.

Conflict and Warfare

- John Easton, Metacomet Explains the Causes of King Philip’s War (1675)

- The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Declaration of Pedro Naranjo

- Pontiac, “The Master of Life”

- Tecumseh, Address to the Osage

- Little Crow, Speech to a War Council

- Chief Joseph, “I Will Fight No More Forever”

- Geronimo, Statement of Geronimo

- Turning Hawk, Captain Sword, Spotted Horse, American Horse, Testimony on Wounded Knee

- Nicholas K. Geranios, “Survivor Returns to Site of Last Indian Massacre”

Governmental Policy

- King George III, Royal Proclamation of 1763

- George Washington, Letter to James Duane

- Petitions of Cherokee Women, 1817, 1818, 1831

- John Ross et al., Letter to John C. Calhoun

- James Kent, Commentaries on American Law

- Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States

- Fort Laramie Treaty

- Courts of Indian Offenses

- Ely Parker, Letter to Harriet Converse

- Richard Henry Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites”

- Theodore Roosevelt, First Annual Message to Congress

- Carlos Montezuma, “Let My People Go!”

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Speech to Calvin Coolidge

- Antonio Luhan, Letter to John Collier

- House Concurrent Resolution 108

- National Congress of American Indians, Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy

- President Richard Nixon, Special Message on Indian Affairs

Civilization, Assimilation, and Education

- Jonas Michaëlius, Letter to Adrian Smoutius

- Samson Occom, A Short Narrative of My Life

- Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites

- Richard Henry Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites”

- President Theodore Roosevelt, First Annual Message to Congress

- Quanah Parker, Speech of Quanah Parker

- Carlos Montezuma, “Let My People Go!”

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Speech to Calvin Coolidge

Religion and Religious Movements

- The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Declaration of Pedro Naranjo

- Pontiac, “The Master of Life”

- Samson Occom, A Short Narrative of My Life

- Red Jacket, Speech of Red Jacket

- Tenskwatawa, Speech of Tenskwatawa

- Tecumseh, Address to the Osage

- Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites

- William Apess, “The Indians: The Ten Lost Tribes”

- Courts of Indian Offenses

- Wovoka, Letter Regarding the Ghost Dance Doctrine

- Turning Hawk, Captain Sword, Spotted Horse, American Horse, Testimony on Wounded Knee

Diplomacy, Negotiations, and Treaties

- Cornplanter, Speech to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania

- Joseph Brant, Speech of Joseph Brant

- Tecumseh, Address to the Osage

- Petitions of Cherokee Women, 1817, 1818, 1831

- John Ross et al., Letter to John C. Calhoun

- Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites

- John Ross, Address at Inter-Tribal Council at Tahlequah

- Fort Laramie Treaty

- Red Cloud, Address at Cooper Union

- Sitting Bull, Testimony before Senate Select Committee

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Speech to Calvin Coolidge

- National Congress of American Indians, Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy

Diminishment, Dispossession, and Loss

- Cornplanter, Speech to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania

- Joseph Brant, Speech of Joseph Brant

- Petitions of Cherokee Women, 1817, 1818, 1831

- John Ross et al., Letter to John C. Calhoun

- Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites

- James Kent, Commentaries on American Law

- Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States

- Red Cloud, Address at Cooper Union

- Sitting Bull, Testimony before Senate Select Committee

- President Theodore Roosevelt, First Annual Message to Congress

- House Concurrent Resolution 108

- Justice Harry Blackmun, Justice William Rehnquist, United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians

Sovereignty, Resistance, and Protest

- Petitions of Cherokee Women, 1817, 1818, 1831

- John Ross et al., Letter to John C. Calhoun

- Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites

- Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States

- Standing Bear v. Crook

- Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Declaration of War

- National Congress of American Indians, Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy

- Indians of All Tribes, Alcatraz Proclamation

- Justice Byron White, California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians

- Standing Rock Sioux, Resolution Regarding Dakota Access Pipeline

- Justice Neil Gorsuch, McGirt v. Oklahoma

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section 1 questions relevant for that document alone and in Section 2 questions that require comparison with other documents.

Jonas Michaëlius, Letter to Adrian Smoutius, August 11, 1628

- Michaëlius, and many who came after him, advocated educating Native children and forgetting about trying to do anything with adults. Why did he and the others so strongly advocate such a strategy? Was this a proper strategy? Why or why not?

- What does Samson Occom’s account of his life tell us about the strategy that Michaëlius advocated?

John Easton, Metacomet Explains the Causes of King Philip’s War, 1675

- Relations between early English settlers and Indians were initially cordial. What were the sources for their cooperation? Why did relations between settlers and Indians sour? What caused conflict between them?

- In what ways did the events leading up to King Philip’s War and the war itself set the pattern for later conflicts?

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Declaration of Pedro Naranjo, December 19, 1681

- What were the reasons for the Pueblo Revolt of 1680? How did the Pueblos go about planning and executing their rebellion against the Spanish?

- The Pueblo Revolt is sometimes called the “First American Revolution”; certainly it was the most successful Indian revolt in history. Why do you think it succeeded when others like those of Tecumseh and Little Crow failed?

Pontiac, “The Master of Life,” 1763

- Who was the Master of Life, and what was his message for Algonkian Indians around the Great Lakes? What were the reasons for Pontiac’s Rebellion and what was its outcome?

- How did Pontiac’s Rebellion relate to later raising-up movements (See Speech of Tenskwatawa and Letter Regarding the Ghost Dance Doctrine)?

King George III, Royal Proclamation of 1763, October 7, 1763

- How did the Royal Proclamation attempt to regulate interaction between whites and Indians? Was the proclamation a wise course? Did it work? How might it have been more effective?

- How has the U.S. government sought to regulate Natives and their interaction with non-Natives? Consider the Fort Laramie Treaty, The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites, and House Concurrent Resolution 108.

Samson Occom, A Short Narrative of My Life, 1768

- This document is the earliest known autobiography by an Indigenous person in North America. Who was Samson Occom and what was his background? What was Occom’s reason for penning this memoir?

- How is Occom’s self-representation similar to other statements by Indians such as Joseph Brant, Red Cloud, and Sitting Bull? How is it different?

George Washington, Letter to James Duane, September 7, 1783

- Who was James Duane, and why would he write to George Washington inquiring about his opinions regarding Indian affairs? Go beyond the simple fact that they were friends. What policies did Washington advocate for how the new United States should deal with Indians, and what do these policies and this letter reveal about his attitudes toward them?

- How does Washington’s advice compare or relate to the Royal Proclamation of 1763 twenty years earlier?

Cornplanter, Speech to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, October 29, 1790

- What was Cornplanter’s purpose in this speech in Philadelphia? What were his complaints? What is the significance of him calling the white leaders in attendance “fathers” rather than “brothers”?

- Which Indian leaders of later eras lodged complaints similar to those of Cornplanter? How do they differ? Consider Address at Cooper Union and Testimony before Senate Select Committee.

Red Jacket, Speech of Red Jacket, 1792

- Red Jacket became famous for his debates with Christian missionaries. What were his objections to bringing the new religion to Indians? What were the chief ’s other complaints against whites and the United States?

- Some Indians differed from Red Jacket in their views on Christianity. Samson Occom, for instance, was himself a Christian missionary to other Indians. Wovoka, the prophet of the 1889–90 Ghost Dance, incorporated Jesus into his raising-up movement. What do you think accounted for these very different reactions to Christianity?

Joseph Brant, Speech of Joseph Brant, April 21, 1794

- Joseph Brant fought for the British during the American Revolution. After the war, like other Haudenosaunee who did so, he moved to Canada, although he moved freely back and forth between both countries. What did he want the new nation to know about the Haudenosaunee?

- Brant used the word “we” throughout his speech. Sometimes this referred collectively to the Haudenosaunee, at other times to himself. After reading the document carefully, what do you think he wanted the United States to know about Joseph Brant? How did Brant’s effort resemble later efforts of Indians like Sitting Bull and Red Cloud on behalf of their peoples?

Tenskwatawa, Speech of Tenskwatawa, 1807

- Tenskwatawa is sometimes called the “Shawnee Prophet.” What message did he have for Indians?

- Tecumseh’s rebellion, fed by Tenskwatawa’s visions, was the second great raising-up movement. What was behind these revitalization movements (See The Master of Life, Letter Regarding the Ghost Dance Doctrine)? What was their appeal? Did they differ in any significant ways?

Tecumseh, Address to the Osage, 1811

- What arguments did Tecumseh make to the Osage, a Plains tribal nation far from the Great Lakes and the Midwest? Tecumseh’s vision was a grand alliance of all Indian tribes against the United States. What were the obstacles to this? What were its inherent weaknesses?

- How was Tecumseh’s rebellion similar to Pontiac’s? How was it different from Wovoka’s Ghost Dance movement?

Petitions by Cherokee Women, 1817, 1818, 1831

- Three petitions by women of the Cherokee Nation are included here. The first two were written at a time the Cherokee were under pressure from the United States to cede their lands in North Carolina. What were the women’s arguments against doing that? The third position, written after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, expressed the women’s opposition to Removal. Why were they opposed to moving west of the Mississippi? What was their line of argument?

- How are the arguments advanced by the Cherokee women in these petitions like those the Cherokee advanced in the letter to John C. Calhoun?

John Ross et al., Letter to John C. Calhoun, February 11, 1824

- In 1802 the federal government signed a compact with the state of Georgia. In exchange for Georgia giving up its claims to western lands, the government committed to removing all remaining Indians from within the state’s borders. John Ross and his fellow Cherokee wrote to the Secretary of War in opposition to the agreement. How did they state their objections? The letter made a novel proposal that would have given Georgia more land. What was it? Was it reasonable? What were the inherent impediments to Ross’ proposal?

- How do the arguments in this letter resemble those of the Cherokee women in their three petitions?

Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites, May 26, 1826

- This speech had multiple purposes. What were they? What evidence did Boudinot offer of the Cherokees’ progress in the process of civilization?

- Since the turn of the nineteenth century, some Cherokees have invested a lot in the project of “civilization.” How does Boudinot’s letter relate to Ruth Muskrat Bronson’s speech to President Coolidge in 1923?

James Kent, Commentaries on American Law, 1828

- Why would farmers’ claim to land supersede that of hunters and gatherers? What was Kent’s position on the sovereignty of Indian tribal nations? How did it relate to Indian or aboriginal title?

- How does Joseph Story’s view of Indian sovereignty relate to Kent’s opinions on their land rights?

William Apess, “The Indians: The Ten Lost Tribes,” 1831

- Why did some whites believe Indians were the Lost Tribes of Israel? What was Apess’ purpose in saying the belief was true? Was this belief on the part of whites positive or negative for Indians? Why?

- William Apess was a Christian, yet many other Indians objected to the new religion the whites tried to impose on them. What reasons did Red Jacket give for his opposition?

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 1833

- What was Story’s view of Indian tribal sovereignty? What was his basis for holding this view?

- How does Story’s view differ from James Kent’s?

John Ross, Address at Inter-Tribal Council at Tahlequah, June 19, 1943

- What was the Inter-tribal Council held at Tahlequah, and what was its purpose? How many tribal nations were invited? How many attended? What did the Inter-Tribal Compact say? Would you judge the council a success? Why or why not?

- Like Joseph Brant, John Ross was, among his other accomplishments, a diplomat. What is the relationship between Ross’ efforts and Brant’s?

Little Crow, Speech to a War Council, August 18, 1862

- What were the reasons the Dakota in Minnesota staged an uprising in 1862? Why did Little Crow tell them it was ill-advised? What did Little Crow tell the warriors he would do? Why do you think he made that decision?

- In what ways were the reasons for Little Crow’s War similar or dissimilar to those of King Philip’s War almost a century earlier?

Fort Laramie Treaty, April 29, 1868

- What events led up to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868? Often, Indians signed treaties because they were coerced. Was this treaty a rare win for Indians? Why or why not? Why did article 6 of the treaty exclude “mineral land.” What do the provisions of the treaty tell us about what the U.S. government thought was best for the Indians? Were the provisions of the treaty realistic?

- When the Seminole were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s, they were promised that their new lands would be theirs for all future time, just as the Sioux were promised the Great Sioux Reservation created by this treaty. In neither case was the promise kept. How did the Supreme Court seek to redress the wrongs done to the Sioux and the Seminole in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians and McGirt v. Oklahoma?

Red Cloud, Address at Cooper Union, June 16, 1870

- What misconceptions about his people did Red Cloud want to dispel in his brief remarks? What was his purpose in addressing a white audience in New York?

- How similar was his purpose to Elias Boudinot’s in his Address to the Whites?

Chief Joseph, “I Will Fight No More Forever,” October 5, 1877

- What were Chief Joseph’s reasons for surrendering to the Army? Put yourself in his position. How must he have felt? How would you have felt?

- Like Standing Bear and Geronimo, Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce left their reservation because they wanted to be left alone. In all these cases they did no harm to the United States. Why was the United States determined to keep them on the reservation?

Standing Bear v. Crook, May 12, 1879

- Standing Bear brought his case for intensely personal reasons, but it had repercussions for Indian people in general. How? A short while after Standing Bear won his case, his brother was shot and killed attempting to leave the reservation in Indian Territory. How can you reconcile that with Standing Bear’s victory? Reservations were viewed as temporary measures. Those who established them saw their purpose as twofold: to protect settlers from Indians and to protect Indians from depredations by whites. Was confining Indians to reservations fair? What, if any, were the alternatives, given the circumstances?

- In the cases of Chief Joseph and Geronimo, the U.S. government devoted significant resources to returning Indians to the reservation. In Standing Bear’s case, General Crook objected to his orders to return Standing Bear and his followers to their reservation in Indian Territory. Why did the U.S. government care?

Sitting Bull, Testimony before Senate Select Committee, 1883

- What things did Sitting Bull want the senators to tell the “Great White Father” (the president of the United States)? He referred several times to his country. What country did he mean? What things did Sitting Bull want Congress (and the president) to deliver to him and his people? What were his rationales for these requests?

- Sitting Bull and Red Cloud are often seen as oppositional figures. For instance, Sitting Bull opposed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. He told Jesuit missionary Pierre Jean De Smet, “I wish all to know that I do not propose to sell any part of my country.” How does his testimony here compare to Red Cloud’s remarks at Cooper Union?

Courts of Indian Offenses, 1883

- The First Amendment promises the free exercise of religion, and yet the “Religious Crimes Code” outlawed American Indian traditional religious practices. Punishment for infractions ranged from denial of food rations to jail, with little discretion left to the courts’ judges. What was the federal government’s purpose in banning Indians’ traditional religions? Do you think it was the correct thing to do? Though such practices went underground and to some extent survived, the rules did a great deal of damage to Native cultures and traditions. Further, the judges on the courts were Indians themselves. How would you have felt as one of these judges?

- How did the Court of Indian Offenses relate to plans for educating Indians like those of Michaëlius and Pratt?

Ely Parker, Letter to Harriett Converse, July 7, 1885

- As General Grant’s adjutant, Ely Parker physically wrote the surrender General Lee signed at Appomattox. After the signing, Lee went up to Parker and said that was nice to see one “real American” in the room. Parker replied that all in the room were Americans. What did Lee mean? What did Parker mean? Parker was a highly accomplished man who because he was an Indian was not permitted to pursue his chosen profession of law. Nevertheless, thanks to his relationship with President Grant, he rose to the pinnacle of power as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He made powerful enemies, though, who forced him out of office. In this letter, what did Parker enumerate as the things he tried to accomplish, and why did some want to bring him down?

- How does Parker’s account relate to Carlos Montezuma’s criticisms of the Bureau of Indian Affairs?

Geronimo, Statement of Geronimo, March 25, 1886

- In this talk Geronimo gave his reasons for leaving the reservation. What were they? What proofs did he offer to back up his claims?

- As with Chief Joseph, Geronimo just wanted to be left alone. Why was the U.S. government so intent on confining Indians to reservations?

Wovoka, Letter Regarding the Ghost Dance Doctrine, 1891

- What instructions did Wovoka give to Indians? What was the appeal of Wovoka’s Ghost Dance movement to Indians? What was going on in their lives at the time?

- Compare Wovoka’s Ghost Dance vision with Tenskwatawa’s? How are they similar?

- Not all Indians believed in the Ghost Dance. Sitting Bull, for instance, was opposed to the movement. These four Indians spoke against the new religion. What were their reasons? In any battle—even a one-sided massacre such as Wounded Knee—there is often a great deal of confusion. On what points do these Indians’ accounts disagree?

- How is the Wounded Knee Massacre different from that of Shoshone Mike and his family (See Survivor Returns to Site of Last Indian Massacre)?

Richard Henry Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites,” 1892

- What kind of education did Pratt advocate for Indians? What did he see as the advantages? Was Pratt’s attitude toward Indians and their education patronizing or paternalistic? Why or why not?

- How do Pratt’s ideas of Indian education compare with those of Michaëlius nearly three centuries earlier?

President Theodore Roosevelt, First Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1901

- Why was the General Allotment Act, which broke up commonly held reservation lands into private property, so important to President Roosevelt? In what terms did he speak about it? What did he say about the education of Indians?

- Compare President Roosevelt’s ideas with those of Richard Henry Pratt. How do they differ?

Quanah Parker, Speech of Quanah Parker, 1910

- What did Quanah Parker want for his people? Why? Did Parker foresee the extinction of Comanches, or was he talking about something else?

- How do Parker’s brief remarks compare with Sitting Bull’s testimony before the Senate committee and Red Cloud’s remarks at Cooper Union?

Carlos Montezuma, “Let My People Go!” September 30, 1915

- What were Montezuma’s objections to federal Indian policy? Why? What course of action did he prefer? What do you think were the influences upon him?

- Compare Montezuma’s criticisms of the Bureau of Indian Affairs with Ely Parker’s account of his tenure as the bureau’s commissioner. See Letter to Harriet Converse.

Ruth Muskrat Bronson, Speech to Calvin Coolidge, December 1923

- The federal government and whites often referred to the “Indian problem.” From their perspective, what was the problem? How did the Indians’ view, as expressed by Bronson, differ? For what things did Bronson ask President Coolidge? What did she see as Indians’ contributions to the United States? How did she say Indian history pointed the way for this and for Indian youth?

- How do the views expressed by Bronson compare with those of Elias Boudinot a century earlier?

Antonio Luhan, Letter to John Collier, 1935

- What was federal Indian policy prior to President Franklin Roosevelt? How did the Indian New Deal differ from it? What was the new policy’s goal? What was the Indian Reorganization Act? What difficulties did Luhan tell Commissioner of Indian Affairs Collier he was encountering in promoting the IRA?

- How did the distrust Luhan encountered relate to the criticisms of Indian policy voiced by Carlos Montezuma?

Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Declaration of War, June 13, 1942

- Why was it important to the Haudenosaunee Confederacy to declare war on the Axis Powers separately from the United States? What is sovereignty? Federally recognized tribes are separate sovereigns within our federal system. They are sometimes referred to as nations within a nation. Is it possible to have nations within a nation?

- The Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma allowed some tribal nations in Oklahoma to expand their jurisdiction, and hence sovereignty, over their reservation lands. Does this perhaps help explain the need of the Haudenosaunee to declare war?

House Concurrent Resolution 108, 1953

- Following World War II, Termination and Relocation became federal Indian policy. This resolution is one manifestation of that policy. What were the policy’s elements? How did it differ from the Indian New Deal? What was the intention of this policy? Was it a wise course? Why or why not?

- How does Resolution 108 relate to Carlos Montezuma’s views expressed in “Let My People Go!”?

National Congress of American Indians, Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy, 1959

- According to the NCAI, what was the condition of Native Americans in 1959? How did this influence the congress’ position on Termination and Relocation? What concrete things did it demand?

- Is there any relationship between the stance of the NCAI on Termination and Relocation and the views expressed by Carlos Montezuma?

Indians of All Tribes, Alcatraz Proclamation, November 20, 1969

- Indians of All Tribes was an ad hoc organization of Indians from different tribal nations. Why did they occupy Alcatraz Island in 1969? What did they hope to accomplish? In this proclamation, what demands did they make? Were these demands realistic? Was realism the point?

- How was the radical activism of the late 1960s and early 1970s, as represented by this proclamation, an outgrowth of Termination and Relocation (See House Concurrent Resolution 108, Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy)? How did the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 factor into the occupation of Alcatraz?

President Richard Nixon, Special Message on Indian Affairs, July 8, 1970

- With this message to Congress, President Nixon formally ended Termination and Relocation. He announced a new federal policy toward Indians: Self-Determination. What were President Nixon’s reasons for this change in policy? What did he hope the new policy would achieve?

- Compare President Nixon’s Self-Determination policy with the Indian New Deal. How are they similar? How are they different?

- The Sioux fought for a hundred years for the return of the Black Hills, their most sacred site. What did the majority of the Supreme Court say about the taking of the Black Hills? Why did Justice Rehnquist dissent? The Sioux were awarded approximately $105 million for the illegal taking of the Black Hills. Why did they refuse to take it? Today, after continued compounding of interest, the unclaimed sum is approximately $2 billion. Do you think it wise to continue to reject the money? What would you do?

- The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 created the Great Sioux Reservation, which included the Black Hills. These lands were promised to the Sioux, but that promise was not kept. How did the treaty factor into the High Court’s decision?

Justice Byron White, California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, February 25, 1987

- The Supreme Court ruled that California could not prevent Indian reservations within its borders from conducting gambling operations on the reservation. What was the Court’s rationale? Were the justices right? Do you think tribal nations should be allowed to operate casinos on their reservations? Is your answer affected by what they do with the money they collect? For instance, would your answer be different if the tribe used the funds to build houses for or educate tribal members rather than disbursing it directly to them or using it to pay government officials’ salaries? Do you think economic diversification—using the money to start and build up businesses other than casinos—would be a better use of the money? What if these enterprises employed tribal citizens?

- How does this decision relate to expressions of sovereignty like the Haudenosaunee declaration of war in World War II and McGirt v. Oklahoma?

Nicholas K. Geranios, “Survivor Returns to Site of Last Indian Massacre,” September 18, 1988

- Some Americans believe that Native Americans disappeared in the 19th century, and most think the Indian Wars ended in 1890. How does it make you feel to know that the last massacre occurred in 1911 when, as the article said, there were cars, airplanes, and motion pictures? Or that the last massacre survivor died only thirty years ago? Do you know people who were alive when Mary Jo Estep passed away? How did Mary Jo Estep feel when she returned to the site of the massacre, where her mother and grandfather were killed? Was she emotional? How would you have felt if it had been you?

- How is the Shoshone Mike Massacre described in this document similar to the Wounded Knee Massacre? How is it different?

Standing Rock Sioux, Resolution regarding Dakota Access Pipeline, September 2, 2015

- Why did the Standing Rock Sioux say they were opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline? Did their reasons perhaps go beyond those stated in the resolution? How do you feel about the pipeline traversing Indian lands and potentially damaging cultural sites? We must transport petroleum somehow, and statistically, pipelines are safer than transporting oil by truck or train. Are there alternatives?

- Can you see any relationship between the protest at Standing Rock and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868? What about to the occupation of Alcatraz (See Alcatraz Proclamation)?

Justice Neil Gorsuch, McGirt v. Oklahoma, July 9, 2020

- Jimcy McGirt was a Seminole man who had committed heinous crimes. What was the Supreme Court majority’s reasoning in ruling that he had been wrongfully tried and convicted by the state of Oklahoma? McGirt was not released by the decision; he would have to be retried in federal court. Does this seem right to you? What does the McGirt decision say about the continued vitality of tribal national sovereignty in the twenty-first century?

- What relationships can you see between the High Court’s decision in this case and that in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians?