Introduction

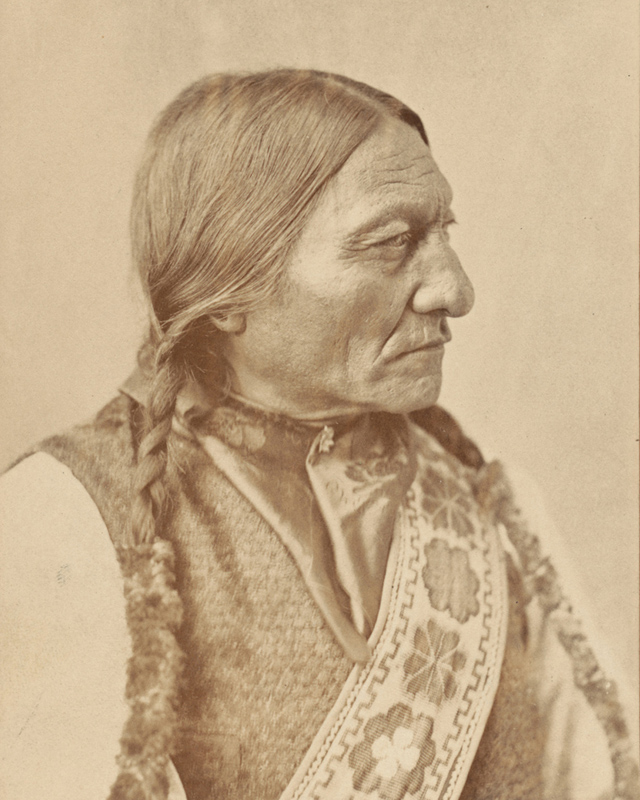

Sitting Bull (c. 1831–1890) is arguably the most famous Native American in U.S. history. After the Fort Laramie Treaty and the creation of the Great Sioux Reservation, many Sioux chiefs like Red Cloud moved onto the reservation. The United States had several goals: to protect settlers from Indians, to protect Indians from the settlers, and to prepare Indians for citizenship by making them small-scale farmers. Unfortunately, lands set aside as reservations were usually not well suited to agriculture. The result was to foster dependence on the part of the Indians. Sitting Bull, however, refused to relocate permanently to the reservation.

In early 1876, following several years of conflict involving surveys for the Northern Pacific Railroad on Indian land and the discovery of gold in the Black Hills—Sioux land according to the Fort Laramie Treaty—hundreds of Sioux and Cheyenne flocked to the camp of Sitting Bull, a renowned medicine man known for his opposition to white encroachment. Eventually, their numbers exceeded ten thousand, the largest Indian encampment ever. When the 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer (1839–1876) attacked, Sitting Bull took no part in the actual fighting but acted as a spiritual advisor.

Following Custer’s defeat, Sitting Bull and his followers fled to Canada. He returned to the United States in 1881 and surrendered. In 1883 he testified before a Senate Select Committee, seeking to dispel popular notions about Indians and challenging the United States to live up to its promises.

Sitting Bull later performed in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West. He was killed on December 15, 1890, by Indian police who had gone to arrest him for fear that he would join the Ghost Dance movement.

—Jace Weaver

Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the 1st Session of the 48th Congress, 1883–84 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1884), no. 283, serial 2164 (1883), 79–81.

. . .If a man loses anything, and goes back and looks carefully for it he will find it, and that is what the Indians are doing now when they ask you to give them the things they were promised them in the past. And I do not consider that they should be treated like beasts, and that is the reason I have grown up with the feelings I have. Whatever you wanted of me I have obeyed, and I have come when you called me. The Great Father sent me word that whatever he had against me in the past had been forgiven and thrown aside, and he would have nothing against me in the future, and I accepted his promise and came in. And he told me not to step aside from the white man’s path, and I told him I would not, and I am doing my best to travel in that path. I feel that my country has gotten a bad name, and I want it to have a good name. It used to have a good name, and I sit sometimes and wonder who it is that has given it a bad name. You are the only people now who can give it a good name, and I want you to take care of my country and respect it. When we sold the Black Hills we got a very small price for it, and not what we thought we ought to have received. I used to think that the size of the payments would remain the same all the time, but they are growing smaller all the time. I want you to tell the Great Father everything I have said, and that we want some benefits from the promises he has made to us. And I don’t think I should be tormented with anything about giving up any part of my land until those promises are fulfilled. I would rather wait until that time, when I will be ready to transact any business he may desire. I consider that my country takes in the Black Hills, and runs from the Powder River to the Missouri, and that all of this land belongs to me. Our reservation is not as large as we want it to be, and I suppose the Great Father owes us money now for land he has taken from us in the past. You white men advise us to follow your ways, and therefore I talk as I do. When you have a piece of land, and anything trespasses on it, you catch it and keep it until you get damages, and I am doing the same thing now. And I want you to tell this to the Great Father for me. I am looking into the future for the benefit of my children, and that is what I mean when I say I want my country taken care of for me. My children will grow up here, and I am looking ahead for their benefit and for the benefit of my children’s children, too; and even beyond that again. I sit here and look around me now, and I see my people starving, and I want the Great Father to make an increase in the amount of food that is allowed us now, so that they may be able to live. We want cattle to butcher—I want you to kill three hundred head of cattle at a time. This is the way you live, and we want to live in the same way. This is what I want you to tell the Great Father when you go back home. If we get the things we want, our children will be raised like the white children. When the Great Father told me to live like his people I told him to send me six teams of mules, because that is the way white people make a living, and I wanted my children to have these things to help them to make a living. I also told him to send me two spans of horses with wagons, and everything else my children would need. I also asked for a horse and buggy for my children. I was advised to follow the ways of the white man, and that is why I asked for those things. I never ask for anything that is not needed. I also asked for a cow and a bull for each family, so that they can raise cattle of their own. I asked for four yokes of oxen and wagons with them. Also a yoke of oxen and a wagon for each of my children to haul wood with. It is your own doing that I am here. You sent me here, and advised me to live as you do, and it is not right for me to live in poverty. I asked the Great Father for hogs, male and female, and for male and female sheep for my children to raise from. I did not leave out anything in the way of animals that the white men have: I asked for every one of them. I want you to tell the Great Father to send me some agricultural implements, so that I will not be obliged to work bare-handed. Whatever he sends to his agency our agent will take care of for us, and we will be satisfied because we know he will keep everything right. Whatever is sent here for us he will be pleased to take care of for us. I want to tell you that our rations have been reduced to almost nothing, and many of the people have starved to death. Now I beg of you to have the amount of rations increased so that our children will not starve, but will live better than they do now. I want clothing, too, and I will ask for that, too. We want all kinds of clothing for our people. Look at the men around here and see how poorly dressed they are. We want some clothing this month, and when it gets cold we want more to protect us from the weather. That is all I have to say