No study questions

No related resources

UNIMPROVED OPPORTUNITIES

There are several things I shall say to you to-night, which may not sound very agreeable or encouraging to many of you, yet you will agree with me that they are facts that cannot be denied,

We have got to recognize, in the first place, that our condition is, in a large measure, different from that of the white race by whom we are surrounded; that our capacity is in a large measure, different from theirs. I know we like to say the opposite. It sounds very well in compositions, does very well for rhetoric and makes a splendid essay for us to make the opposite assertion, It sounds very well in a newspaper article sometimes; but when we come down to the hard fact of the matter, we must acknowledge that our condition and our capacity are not equal to those of the white people with whom we come in daily contact. Of course, that doesn’t sound very well. To say that we are equal to the whites, is to say that slavery was no disadvantage to us. That is the logic of it. It is saying that slavery was not a disadvantage, but an advantage, in that we were able to remain in slavery for nearly two hundred and fifty years, and then come out with a capacity equal to that of any other race. To illustrate — suppose a person is confined in a sick room, deprived of the faculties, use of his body and senses, and then he comes out and is placed by the side of a man who has been healthy in body and mind — is the condition of those two persons equal? Are they equal in capacity? Is the young animal of a week old, though he has all the elements that his mother has as strong as she? With proper development it will, sometime in the future, be as strong, but it is unreasonable to say that it is now as strong as its mother. And so, I think, this is all we can say of ourselves — with proper development our condition and capacity will be the same as any other race’s.

Now, this difference in condition and capacity, demands certain difference in education, a certain difference in training. True, we have a great many disadvantages, still we have the opportunity of learning at this stage of our growth and education, a great deal from the mistakes of the white race. The white race has been two or three thousand years getting to the point where it has learned that it has made a mistake in confining education to the head, and not coupling that education on to matter — not dove-tailing mind into matter. The white race has only learned that within the last dozen years. All that has been done in the way of industrial education has come about within the last dozen years. I say the white race has been three thousand years discovering this error, while, within the last twenty-five years, we are born right into this thing, where we can take advantage of all mistakes that the white race has been making during all this time. In this we have a great advantage.

Our children have educational advantages that thousands of white children never did have. Take the President of the United States; the smallest boy on the grounds has four or five times the chances he had in the way of education. Tell a white man forty or fifty years old about Kindergartens — about learning the alphabet without going through the old humdrum method, and he will tell you he knew nothing about such a thing. Here our children are born into this thing. They have an opportunity to take advantage of all the mistakes the white race has been so long learning, and which they have learned at such a cost of labor.

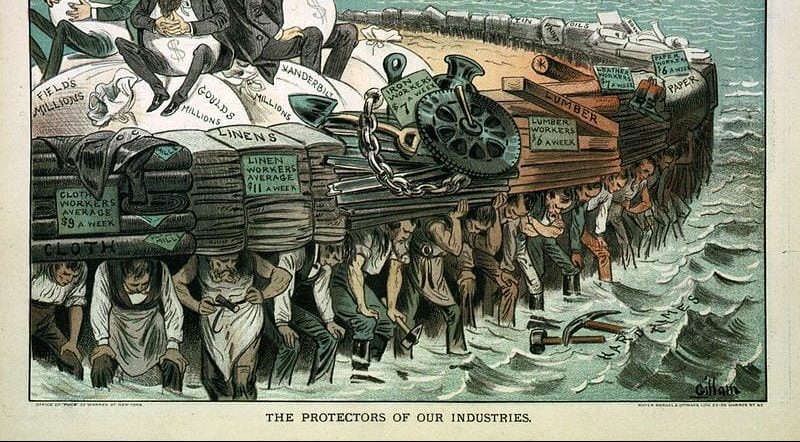

In the first place, our condition is not the same as’ that of other people, because, as a race, as I have often said, we are hungry. I was talking with President Calloway, of Alcorn, a few days ago, regarding the condition of things as they exist in the Mississippi bottoms and throughout the State of Louisiana, and he says that the colored people in those sections are hungry. I have had letters only this week from South Carolina and other States, and the one general piece of news they contain, is that the colored people are hungry. Of course, that does not sound well. It would not be very appropriate for a Fourth of July oration, to say that our people are hungry. Of course, we may not be feeling the pangs of hunger, and have clothing and get along very well, but there is still hunger among the masses. They are hungry in that they are without food, clothing, shelter, bank account — without the things that constitute the foundation of life. If you will agree with me that we are hungry as a race, that is, we are without the material necessities that any race must have before it can rise very far; if you agree with me in that, then isn’t it most sensible in giving all our time and strength toward supplying the things that we most stand in need of?

Understand me, I am not now, nor have I ever been, opposed to any man or woman getting all the education they can. It does not matter where they get it or how they get it; what are they going to do with it, is the question. What we need to do for the next fifty or one hundred years, is to apply that education in the direction of conquering the forces of nature — to conquering matter. In other words, the power of that education, whether it be much or little, the whole strength of it should be applied during the next fifty or hundred years, in the direction of filling up our stomachs — I mean in that larger and wider sense, in supplying food, shelter, raiment — something that we can lay by for a rainy day.

In Scotland, where higher education has been within the reach of the people for many years, and where the people have reached a high degree of civilization, it is all right for the young people to give their time and attention to the study of metaphysics, law and the other professions. Of course, I don’t mean to say that we should not have lawyers, metaphysicians and other pro-fessions men after a while, but I do mean to say that the efforts of a large majority of us should be devoted to securing the more material necessities of life.

THE OBJECT OF INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION

When you speak to the average person about labor, industrial work, especially, he gets the idea at once that you are opposed to his head’s being educated — that you simply want to put him to work. Anybody who knows anything about industrial education, knows that it teaches a person just the opposite — how not to work. It teaches him to make water work for him, to make air, steam and all the forces of nature work for him. That is what is meant by industrial education.

Now, for a few illustrations: Yesterday I was over in the creamery, and was greatly interested in the process of separating the cream. The only energy that was spent was in turning a crank. The apparatus had been so constructed as to utilize the natural forces, and with the exception of the crank movement, it can be said that that process of separation was brought about by the force of nature. Now, compare the old method of butter-making with the new. Before, you had to go through a long process of drudgery before the cream could be separated from the milk, and then another process of drudgery before the milk could be turned into butter, and even then after churning three or four hours at a time, you got only a spoonful of butter. Now, what we mean by giving you an industrial education is to teach you how to put brains into your work, so that, if your work is butter-making, you can simply stand and turn a crank and produce butter. Now, that is what some people call teaching.

If you are studying chemistry be sure to get all you can out of the course here, and then go to a higher school some where else. Become as proficient in the science as you can. When you have done all this, don’t be content to sit down and wait for the world to honor you because you know a great deal about chemistry — you will be disappointed — but if you want to make the best use of your knowledge of chemistry, come here in the South and use it in making this poor land rich, and in making good butter where we have had poor butter before. In this way you will find that your knowledge of chemistry will cause others to honor you.

During the past twenty-five or thirty years, we have let some golden opportunities slip from us, and I fear we have not had enough plain talk right on these lines that I am mentioning to you now. If you ever have the opportunity to go into any of the large cities of the North, you will see some striking examples of this kind of thing. I remember that the first time I went North — and it hasn’t been so many years ago — it was not an uncommon thing for one to see the barber shops in the hands of colored men. I know colored men who could have gotten comfortably rich. You cannot find to-day in the city of New York or Boston, a first-class barber shop in the hands of a colored man. Something is wrong — that opportunity is gone. Coming home, you go to Montgomery, Memphis or New Orleans, and you will find that the barber shops are gradually slipping from the hands of the colored men, and they are going back on these dark streets and opening little holes. These opportunities have slipped from us largely because we have not learned to dignify labor. The colored man puts a little dirty chair and a pair of razors into a dirtier looking hole, while the white man opens up his shop on one of the principal streets or in connection with some fashionable hotel, fits it up in fine style, with carpets, fine mirrors, etc., and calls that a tonsorial parlor. The proprietor sets up at his desk and keeps the books and takes in the cash. He thus transforms what we call a drudgery into a paying business.

And still another. You remember that only a few years ago and one of the best paying positions that a very large number of colored men were doing, was that of whitewashing. A few years ago it would not have been hard to see colored men around Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, carrying a whitewash tub and a long pole into somebody’s house to whitewash the walls. They very often not only whitewashed the wails, but the carpets and pictures as well. You go into the North to-day, and you will find a very few colored men whitewashing. White men learned that they could dignify that work, and so began to study the work in schools. They became acquainted with the chemistry composing the various ingredients, learned decorating and frescoing, and now they call themselves House Decorators. Now, that’s gone, to come no more perhaps. Now, that these men have elevated this work and added more intelligent skill to it, do you suppose that any one is going to allow some old man with a pole and a bucket to come into his house?

And then there is the matter of cooks. You know that all over the South we have held, and hold now, to a large extent, the matter of cooking in our hands. Wherever there is any cooking to be done, a colored man or woman .does it. But, while we have something of a monopoly of this work, it is a fact that even this is gradually slipping away. People do not always want to eat fried meat, and bread that is made almost wholly of water and salt. They get tired of that, and they want a person to cook for them who will put brains into the work. To meet this demand, white people have transformed what formerly was the menial occupation of cooking, into a profession they have gone to school and studied how to elevate the work, and if we judge by the almost total absence of colored cooks in the North, we are led to believe that they have learned how. And even here in the South they have gradually disappeared, and unless they get a hustle on them-selves, they are going to be completely left. In the North they have disappeared because they have not kept pace with the most improved methods of cooking, and because they have not realized that the world is moving rapidly in the march of civilization. A few days ago when in Chicago, I noticed in one of the fashionable restaurants a fine looking man, well dressed, who seemed to be the proprietor. I asked who he was, and was told that he was the “chef,” as he is called — the head cook. Of course I was surprised to see a man dressed in such a stylish manner and presenting such an air of culture, filling the position of chief cook in a restaurant, but I remembered then, more forcibly than ever, that cooking had been transformed into a profession — into dignified labor.

And still another opportunity is going, and we laugh when we mention it. When we think of what we could have done to elevate it in the same way that white persons have elevated it, we realize that after all it was an opportunity, and that opportunity was that of bootblacking. Of course, here in the South we have that to a large extent, because the competition is not quite so sharp as in the North. You go into Montgomery and want to get your shoes blacked. Very soon you will meet a boy with a box thrown over his shoulders. When he begins to polish your shoes you will very likely see that he uses a very much worn shoe brush, or worse still, a scrubbing brush, and unless you watch him very closely, the chances are he will polish your shoes with stove polish. But you go into any Northern city, and you will find that such a boot-black as you meet in Montgomery doesn’t stand any chance of making a living. White boys, and even men, have opened shops which they have fitted up with carpets, pictures, looking glasses, large comfortable chairs, and very often their brushes are run by electricity. They have the latest newspapers always within reach, and so they make money and get rich. The proprietor of such an establishment is not called a boot-black; he is called the proprietor of such and such a “Shoe-blacking Emporium.” Now that’s gone to come no more. Now there are many colored men perhaps who understand a great deal about electricity, but where is the colored man who would apply that knowledge of electricity to running brushes in a boot-black stand?

In the South, it is a common thing that when a person gets sick, they always notify the old mammy nurse. But a few days ago I saw an advertisement in an Atlanta paper for a number of persons desiring to become trained nurses. We have had a monopoly of the nursing business for the last fifteen years, and the common opinion up to a short time ago was that no body could nurse but one of these old mammies, but that idea is becoming dissipated. In the North when a person gets sick, he does not think of sending for any one but a professional nurse, one who has received a diploma from some nurse training school or a certificate of proficiency from some reputable institution.

I hope you have understood me in what I have been trying to say of these little things. They all tend to show that if we are to keep peace [pace?] with the progress of civilization, we must pay attention to the small things as well as the larger and more important things in life. They go to prove that we have got to put brains into what we do, and if education means anything at all, it means putting brains into the common affairs of life, and making something of them, and that is what we are seeking to tell to the world through this institution’s work.

There are so many opportunities all about us where we can use our education. In all of these matters we place ourselves in demand. You very rarely see a man who knows all about house building, who knows how to draw plans, to test the strength of materials that enter into the making of a first-class house, out of a job. Did you ever see such a man idle? Did you ever see that man writing letters applying for work at this place and that place? People are wanted all over the world who can do work well. Men and women are wanted who under-stand the preparation and supplying food — I don’t mean in the small and menial sense, but who know all about it. Even here is a great opportunity. A few days ago I came in contact with a woman who has spent several years in this country and in Europe studying the subject of food economics in all its details. I learn that this person is in constant demand by institutions of learning and other establishments where the preparation and purveying of food are an important feature. She spends a few months at various institutions. She is wanted every-where because she has applied her education to one of the most important necessities of life.

And so you will find it all through life, especially for the next fifty or one hundred years, that those persons who are going to be constantly in demand, constantly sought after, are those who make the best use of their opportunities, who work unceasingly to become proficient in whatever they attempt to do. Always be sure that you have something out [of] which you can make a living, and then you will not only make yourself independent, but will be in a better position to help your fellow men.

I have spoken about these matters because I consider them the foundation of our future success along all lines. We often hear of a man who has moral character; a man cannot have moral character unless he has something to wear and something to eat three hundred and sixty five days in the year. He can’t have any religion either. You will find that at the bottom of much crime, is the fact that criminals have not had the common necessities of life supplied them. They must have some of the comforts and conveniences — certainly the necessities of life supplied them before they can be morally what they ought to be, or religiously what they ought to be.

In re Debs

May 07, 1895

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.