Introduction

Rachel Calof (1876–1952) was born in Russia and raised in poverty. Eventually, she became the housemaid for a rich relative. Calof was well fed and housed in this home but still poor and without prospects, especially for marriage. When she was eighteen, Calof agreed to marry a young Jewish man who was already in America and intended to settle in northeastern North Dakota. Calof traveled on her own to America and her promised husband, and began her life as a pioneer. In 1936 she wrote an account of her life, which her family eventually translated from Yiddish into English. Her account was not published until 1995.

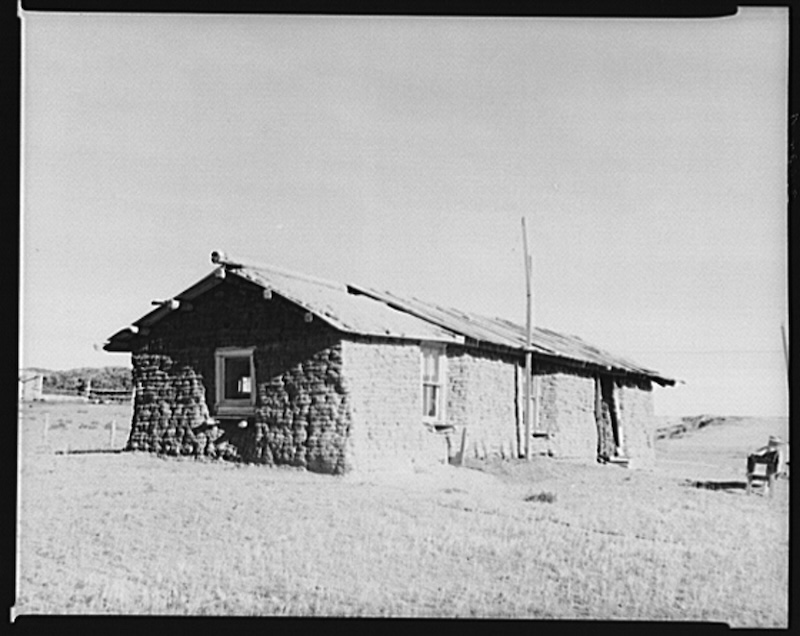

This excerpt begins when Calof arrives with her husband, Abraham, at the homestead in North Dakota. Initially, Rachel and Abraham shared a sod house there with her husband’s family—his parents and two brothers, and the wife of one of the brothers. The extended family lived in three shacks, except when they huddled together in one to survive the bitter first winters, but shared food and farm work. Gradually, and through great hardship, Rachel and Abraham acquired the resources to establish a home and farm of their own.

Source: Rachel Calof, Rachel Calof’s Story: Jewish Homesteader on the Northern Plains, J. Sanford Rikoon, volume editor (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 23, 25, 67, 68–69, 75–77, 81, 85–87, 90–91.

As we climbed down from the wagon I looked again at this assembled group and my heart sank still lower. The two brothers were so dirty and unkempt. They had wild, unshaven faces. Their skin was broken out in big pimples and they wore rags wrapped around their feet in place of shoes. I learned that the women had no shoes at all but were wearing the men’s shoes this day in my honor.

Even this dismal spectacle was inadequate to prepare me for the scene inside the miserable shack which was this woman’s home. As we entered my heart turned to ice at what greeted my eyes. This was my first sight at what awaited me as a pioneer woman. The furniture consisted of a bed, a rough table made of wood slats, and two benches. The place was divided up into two sections, the other being the kitchen which held a stove and beside it a heap of dried cow dung. When I inquired about this, I was told that this was the only fuel this household had. They had no firewood at all. What a terrible way to live. I silently vowed that my home would be heated by firewood and that no animal waste would litter my floor. How little I knew. How innocent I was. Shock and deprivation were no strangers in my young life, but seeing what faced us in this new and hostile environment I could hardly choke back my tears of grief. Two children were inside, a girl and a baby boy. The little girl’s feet were wrapped in rags. She had never owned a pair of shoes. . . .

Each of these three shanties was twelve by fourteen feet, I was told, with dirt floors. They could be moved from place to place if needed, and in times to come such mobility became necessary. Each shack was located on the land which each family intended to file on as a homestead.[1] The government offered a quarter section of land to any adult who would cultivate the ground. Each quarter consisted of one hundred and sixty acres. The land had to be satisfactorily cultivated within fourteen months; if not, the homesteader, if he wished to remain on the land, had to buy it at one dollar and twenty-five cents per acre. If the government was satisfied with the development of the quarter section, the homesteader would receive title to one hundred and sixty acres at the end of five years. At the end of the five-year period, if it was found that the homesteader had farmed more than the original quarter section, he would have to wait an additional six weeks for title to his one hundred and sixty acres and pay a twenty dollar penalty. Single women were permitted the same homestead rights as men but married women did not have such entitlement.[2] Of course all engaged girls in this territory filed claims before marriage. . . .

At last Abraham arrived.[3] He brought two buckets of coal, twenty-five cents worth of sugar, a pound of coffee, and some supposedly pickled herring which upon examination turned out to be, horror of horrors, pickled pigs feet. Considering our condition, you may draw your own conclusions as to whether Abe or I disclosed the true contents of the container which held this particular food. Also included in the bonanza were a pound of butter and, best of all, some ointment for Hannah’s arm.[4]

We were jubilant at our good fortune which seemed even greater considering its timely arrival. Indeed we cried with joy. Such was the nature of our stark and simple life. Little things made the difference between tragedy and happiness in a matter of minutes. Our lives were uncomplicated. Our purpose was survival, and through survival the hope that somehow the future would treat us more kindly than had our past. I did not inquire of my children born into that kind of world whether they considered their lives good or bad. My function was to raise them to a point in time when they could take charge of their own destiny. My role was basic motherhood. There was no time or resources for anything else.

As was our custom, we shared the food and even the few pounds of coal three ways.

I cannot say how much the medicine helped but miraculously Hannah’s arm began slowly to heal. The mortified flesh continued to fall away for some time, but new tissue formed underneath and she improved. . . .

I think that the children of the pioneers came into the world with a certain hardiness of nature in preparation for the harsh conditions awaiting them.

As the weather moderated, Abe took additional loads of hay to town and we improved our food supply. Less fuel was needed as the days became warmer. He realized how close we had come to catastrophe and he was determined not to let it happen again if he could help it.[5]He even insisted that his older brother Charlie carry a load into town. Abe tried hard to make the other men understand that he could not carry such a large measure of responsibility in providing for the three families. He warned the others that they must begin to contribute more to their own welfare.

The result of this was that Charlie did carry a load of hay to market, but he shared his purchases only with his parents and younger brother. I was not surprised.

The wilderness is always unpredictable, often unpleasantly so. The coming of spring weather found the prairie still covered by a great depth of snow. The rains came heavily one night and, with added snowmelt, in a few hours the water was as deep inside the house as it was outside. I put both children on my lap, covered them with our usual stock of rags, and waited for the waters to subside. An umbrella would have been nice, but we did our best without.

Developments during the following summer again gave us added reason to hope that our chances of surviving on the land were improved. Abraham’s share of the farmed land now was ten acres, a large part of which he had planted in wheat, and we estimated that our yield would be about two hundred bushels. We built a barn this summer and we had quite a lot of potatoes, which was my personal project, working in the potato patch with my children by my side. The cow had calved. Now we were getting milk and butter and these were especially welcome. Our new chicken flock rose to about fifty. This was our best summer by far. Considering that the weather was as extremely hot as the winter had been cold and that there were many hailstorms, we did very well. . . .

Despite our increasing hardships and setbacks, we were making slow but steady progress in establishing ourselves on the land. In the past we had farmed communally, but now each family had its own crops. Although we all joined in the common work of stacking hay, shocking grain,[6] and engaging in other mutual tasks, we no longer shared the common wealth. The results of our labors belonged only to us.

Abe was a good manager. He had more grain to sell than the others. I tended the stock when he went to town, a trip which now took only two days if weather conditions were favorable.

Many days we worked side by side in the field with the little ones close by. Too, we had acquired more land and planned to have even more.

Eventually, Abe, without prior experience, built a fine home for us with a full attic which became the children’s bedroom and full cellar as well. But this came to pass at a later date.

We were moving in the right direction but we had learned well the lessons of the past. We knew that sudden and fearful misfortune was ever close on the open prairie. We were terribly vulnerable and we never forgot it. Before this year had passed we would have another vivid reminder of our frailty.

This year [1900] we had planted most of the land in wheat. We had great expectations that this would be our first real crop. We dreamed that we would be able to build the dream house and even have enough money left for a few luxuries.

The wheat grew well and, at last, was ready for cutting. On a fine clear morning Abe checked our boundary lines and made other preparations, for on the following morning we were to begin to reap the golden harvest. Our spirits soared. A better life awaited just ahead.

Dear reader, it was not to be. Before this day born in hope and promise was over, we had been sent reeling back into our former desperate state.

Shortly after the noon meal a dark cloud suddenly boiled up in the northwest sky. We both knew what such a formation could mean and we watched in fear and trembling as the sky became darker and assumed an ominous hue. Then suddenly the hailstorm, the scourge of the prairie farmer, was upon us. It was of such intensity that in a few minutes practically all for which we had suffered and labored so long was destroyed.

The wheat crop was hammered into the ground. The storm water washed away the grain which had already been cut and lay on the ground tied in bundles. Our two horses were killed running frantically into the wire which surrounded their pasture. The windows of the shack were smashed. Destruction was everywhere. We all, children and parents, huddled under the table for protection, but the shack became so filled with water we feared we would be carried away.

The storm passed as quickly as it came, and we surveyed the wreckage it had left behind. Ruin and desolation lay all about us. No wheat crop, no hay, the horses dead, the shack full of water, windows broken out. The soil itself was torn and warped.

I suppose this was a good time and reason as any to give up the long unequal struggle. But we had become resilient and tempered by hardships, and surprisingly, our first emotions were joy and thankfulness that we had been spared. We knew now that we could win out. We had come very close to success this time. Next year might well be the year of fulfillment. I looked at my children and was happy that we were still all in one piece.

A number of the settlers were unable to recover from this disaster and had to leave their land. Many cows in our area died of starvation that year as a result of the devastation caused by this storm, and many people suffered from hunger as well. . . .

Now established in the new house, we slowly began to rebuild our fortunes so thoroughly battered by the great hailstorm. The following year we brought in a fine wheat crop and made progress in other ways as well. We were experienced now and began to feel a growing sense of relationship with the land. We no longer thought of ourselves as strangers in an alien environment but rather as permanent, responsible citizens.

Even though we still endured many hardships and disadvantages, in other ways we were progressing toward a more civilized life. The year after Abe built our home he and Charlie were able to purchase some furniture in town, which they divided. For a long time I felt I must be dreaming to actually have real furniture.

Elizabeth was born to us on a day in November so unbearably cold that we could not keep the house warm. My children huddled about me and I couldn’t fully undress, but I attended to my chore.

Although we were increasingly comfortable on the land, we were always aware of our vulnerability to the elements. We had learned all too well about unrelenting cold, so damaging to body and spirit. We knew firsthand about savage storms which could in a matter of minutes destroy the hard-won fruits of years of labor and deprivation.

The Great Plains, so sparsely populated, spawned fierce cyclones which swept across the prairie with little to stop them. In the hot summers, great whirling winds drove across the flat land and with no obstruction to break them up soon formed into cyclones.

One summer day our immediate area was struck by such a storm. Fortunately I saw the black cone approaching and had time to gather the children into the cellar which served as our storm shelter. Abe was in the field, and I could only hope that he would find some kind of shelter too. . . .

By 1910 we had succeeded in our endeavors. The farm was prosperous and many times the size of the original claims. Abe was also buying and breaking wild horses, an occupation which earned him numerous injuries. We were now prominent and respected throughout North Dakota.

Our home became the center of all the Jewish holiday celebrations. Jewish farmers came from far and near to gather at our home for these occasions, some traveling for days by horse and buggy and by horseback.[7] These were wonderful and festive events. Everyone stayed for as long as the holiday lasted. We put up tents for visiting children’s sleeping quarters, and in the house sleepers occupied all the chairs and covered the floors.

Our house lights now were kerosene powered. The fuel was forced into a tank with a bicycle pump and then to light fixtures which were made with cloth mantles. The mantles gave off an intense white light, travelers on the prairie oriented themselves by this beacon, while to approaching guests it signaled that their haven was near. Another benefit of our distinctive lights was to keep bothersome wild animals from our door and the chicken coop.

We had plenty of food now. Each late fall now, the shochet[8] paid us a visit for the coming winter. The dressed animals were stored in the barn which served as our winter freezer.[9] What a contrast to the slow starvation of the early winters. . . .

Now at age sixty, and thinking back through this history, I feel a satisfying pride in myself. I stood shoulder-to-shoulder with my husband and proved capable in meeting the challenges which so many of the settlers failed to survive. I took life as it was presented to me and then did my best to improve it.

Although I withstood privation well, having been introduced to it at a very early age, I must confess that the one hardship which was always unacceptable to me through the formative years was the lack of privacy. For many months of each of those years Abe and I had to find our privacy on the open prairie, and even in later years we had to hold our personal conversations in the barn.

In those precarious winters of the first years when so many people, and animals as well, huddled together in a tiny space, my yearning was not for a larger shack but rather for the dignity of privacy.

My resentment of this imposition grew with each succeeding year and finally it became a serious issue between Abe and me. In all other risks and discomforts our cause was a common one, but in this one matter I became more unwilling to compromise with each passing year.

The year 1917 was one of sober reflection and decision for Abe and me. In many ways we were comfortable and satisfied. We could look back with pride on our accomplishments. We had come as raw immigrants without resources or training to a stark wilderness in a strange country, and we tamed the land and made it fit for humans. We had earned the respect and friendship of many.

Laughter came easier now, and the memories of past bitter experiences had softened with age, but time and privation had taken their toll. Abe now suffered greatly with rheumatism and my own health was impaired. We realized that the rigors of the farming life were too much for us to endure longer, that it was time to move on to another kind of life.

I had traveled a long and often torturous way from the little shtetl[10] in Russia where I was born. It wasn’t an easy road by any means, but if you love the living of life you must know the journey was well worth it.

- 1. Calof here briefly describes the provisions of the Homestead Act (1862, but subsequently revised).

- 2. Under the legal doctrine of coverture, imported into American law from English common law, a woman’s legal status became “covered,” or contained within her husband’s, when she married. Thus, a married woman could not own land, for example, while a single woman could. This doctrine was slowly removed from American law during the course of the nineteenth century.

- 3. Abraham had gone to town to sell some farm produce to buy supplies.

- 4. Hannah was Rachel’s baby, accidentally burned at birth.

- 5. The family had nearly starved and frozen to death during the harsh winter

- 6. Stacking grain in the field.

- 7. The Devil’s Lake area of North Dakota, where Rachel and Abraham lived, was home to many Jewish families.

- 8. Someone who butchers animals in accordance with Jewish law.

- 9. Dressed animals are animals that have been prepared for cooking.

- 10. A Jewish town or community.

A Sunday Evening Talk

February 10, 1895

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.