No related resources

Introduction

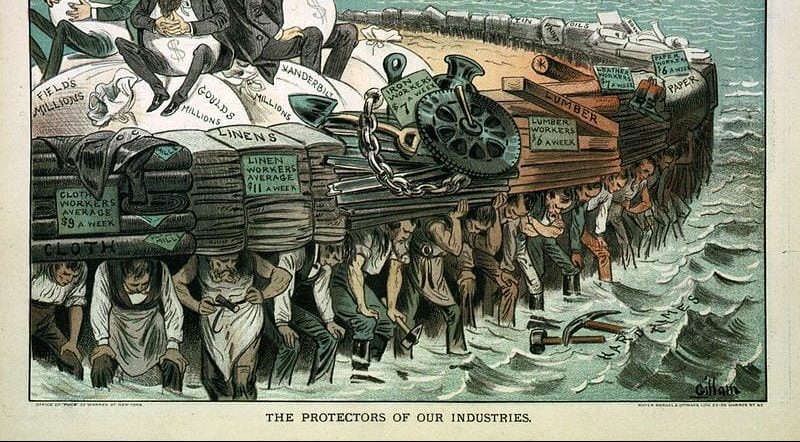

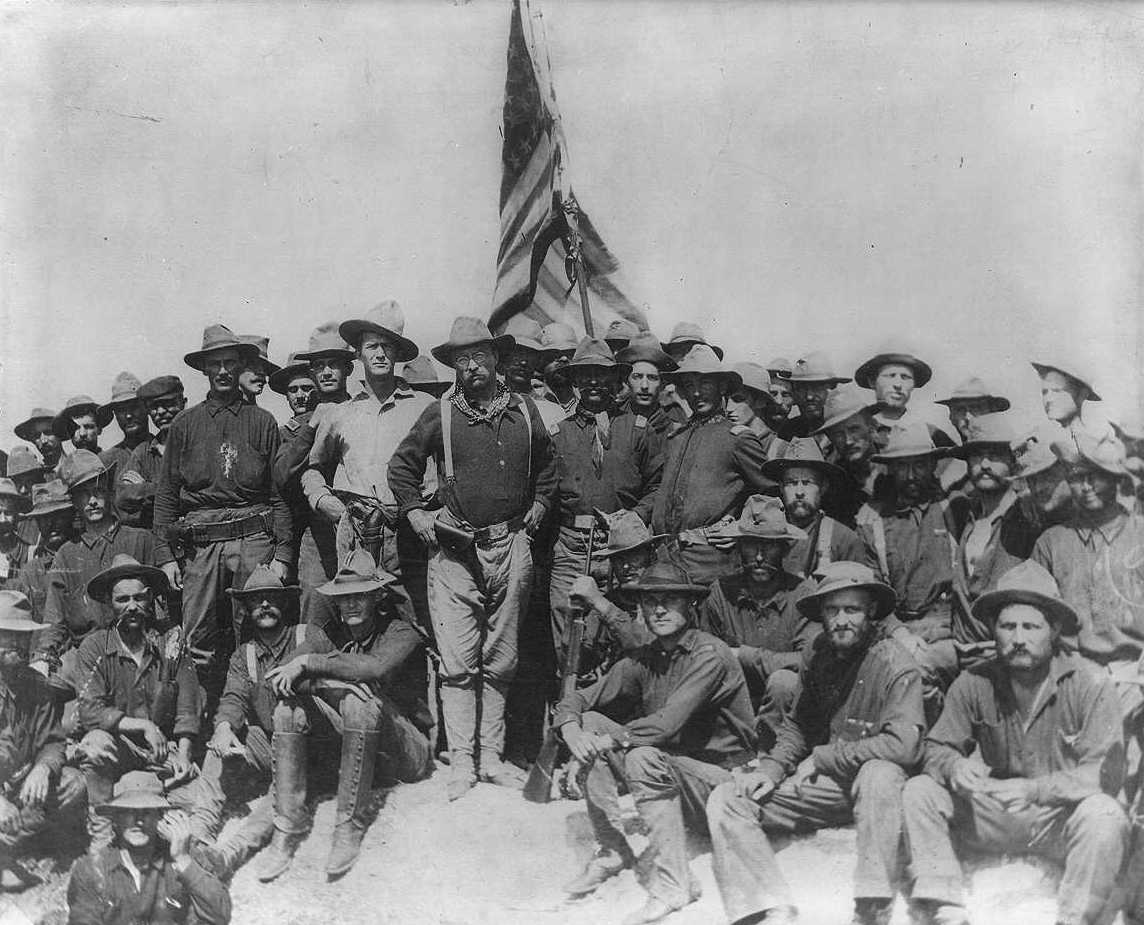

A recession in 1893 led the Pullman Sleeping Car Company to reduce the wages of its workers. When it reduced wages, however, the company did not reduce rents in the housing it supplied to workers. As a result, the workers went on strike on May 11, 1894. Eugene V. Debs (1855–1926) had recently organized the American Railway Union (ARU). Although at first reluctant to get involved, he eventually seized on the Pullman strike as an opportunity to organize Pullman workers and add them to the Railway Union’s members. The Pullman Company refused to recognize the union. To make the strike effective, Debs organized a boycott of any train that had a Pullman car. Other labor leaders and labor organizations opposed the boycott, but ARU members around the country were able to disrupt interstate rail traffic, including that which carried the U.S. mail.

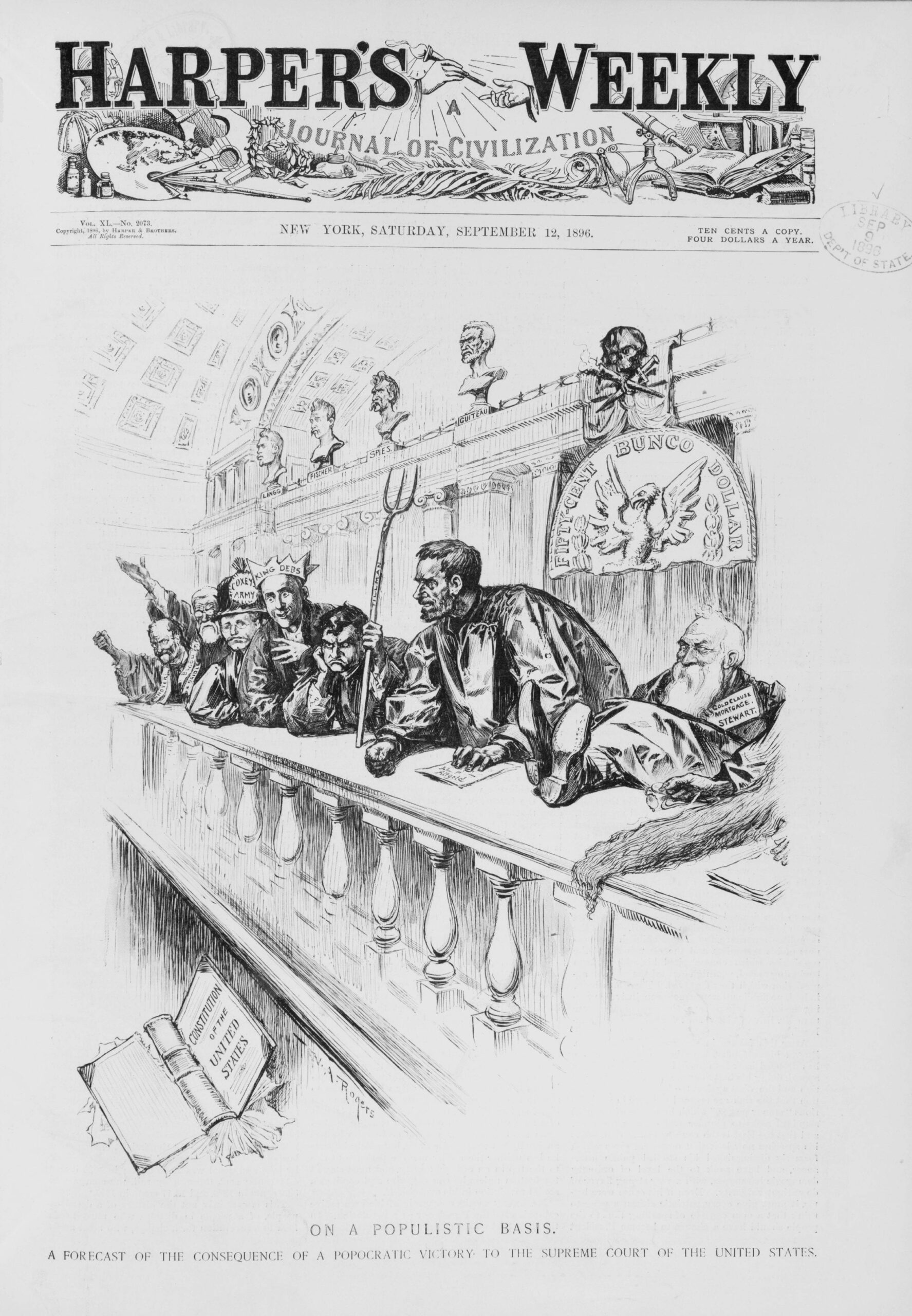

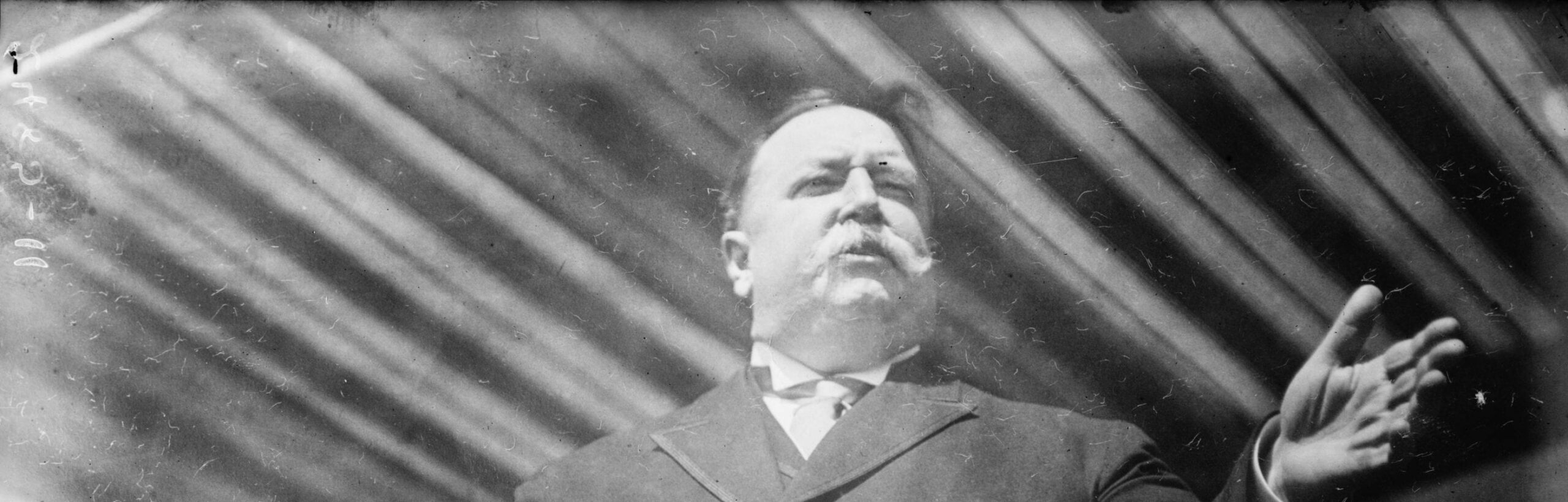

To get the mail moving, President Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) ordered U.S. attorneys and the Army to deal with the strike, which had included acts of violence against trains and other railroad property. (The governor of Illinois, who viewed the strike as a state and local matter, claimed that Cleveland had no constitutional right to do so.) A federal court issued an injunction barring the union from hindering railroad traffic. Debs ignored the injunction. He was arrested on federal contempt and conspiracy charges. The conspiracy charge was dropped, but he was ordered to jail for contempt. His attorneys appealed. The Supreme Court decided unanimously (In re Debs, May 7, 1895) in favor of the U.S. government and the power of the federal courts to issue an injunction against the strike.

The Supreme Court’s decision was a setback for labor, as lower courts proved willing in ensuing years to issue the injunctions that the Supreme Court had approved. Outside the courts, however, organized labor was finding its place in American life. This happened in part because organized labor appealed to the American tradition of liberty and individual rights—the “spirit of ’76” that Debs mentioned in his speech. In a conciliatory move, six days after the Pullman strike ended, Congress passed, and Cleveland signed, a law that established Labor Day, a national holiday honoring workers. In 1932, the Norris–La Guardia Act gave unions full freedom of association and outlawed the kind of injunctions the Supreme Court had approved to end the Pullman strike.

Debs was the Socialist Party’s candidate for president five times (1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, 1920), gathering his highest percentage of the vote in 1912 (6 percent). After speaking out against America’s participation in World War I, Debs was arrested and convicted under the Sedition Act of 1918. He was sentenced to ten years in prison, from which he ran for president in 1920. President Harding commuted his sentence in 1921. Debs gave the speech excerpted here after serving his six-month sentence for contempt for defying the court injunction.

Source: Debs: His Life, Writings and Speeches (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1904), 337–344, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59110/59110-h/59110-h.htm.

Manifestly the spirit of ’76 still survives. The fires of liberty and noble aspirations are not yet extinguished. I greet you tonight as lovers of liberty and as despisers of despotism. I comprehend the significance of this demonstration and appreciate the honor that makes it possible for me to be your guest on such an occasion. The vindication and glorification of American principles of government, as proclaimed to the world in the Declaration of Independence, is the high purpose of this convocation.

Speaking for myself personally, I am not certain whether this is an occasion for rejoicing or lamentation. I confess to a serious doubt as to whether this day marks my deliverance from bondage to freedom or my doom from freedom to bondage. Certain it is, in the light of recent judicial proceedings, that I stand in your presence stripped of my constitutional rights as a freeman and shorn of the most sacred prerogatives of American citizenship, and what is true of myself is true of every other citizen who has the temerity to protest against corporation rule or question the absolute sway of the money power. It is not law nor the administration of law of which I complain. It is the flagrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of law and the usurpation of judicial and despotic power, by virtue of which my colleagues and myself were committed to jail, against which I enter my solemn protest; and any honest analysis of the proceedings must sustain the haggard truth of the indictment.

In a letter recently written by the venerable Judge Trumbull that eminent jurist1 says: “The doctrine announced by the Supreme Court in the Debs case, carried to its logical conclusion, places every citizen at the mercy of any prejudiced or malicious federal judge who may think proper to imprison him.”. . .

The theme tonight is personal liberty; or giving it its full height, depth, and breadth, American liberty, something that Americans have been accustomed to eulogize since the foundation of the Republic, and multiplied thousands of them continue in the habit to this day because they do not recognize the truth that in the imprisonment of one man in defiance of all constitutional guarantees, the liberties of all are invaded and placed in peril. In saying this, I conjecture I have struck the keynote of alarm that has convoked this vast audience.

For the first time in the records of all the ages, the inalienable rights of man, “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” were proclaimed July 4, 1776.

Strike the fetters from the slave, give him liberty, and he becomes an inhabitant of a new world. He looks abroad and beholds life and joy in all things around him. His soul expands beyond all boundaries. Emancipated by the genius of Liberty, he aspires to communion with all that is noble and beautiful, feels himself allied to all the higher order of intelligences, and walks abroad, redeemed from animalism, ignorance, and superstition, a new being throbbing with glorious life. . . .

. . .As Americans, we have boasted of our liberties and continue to boast of them. They were once the nation’s glory, and, if some have vanished, it may be well to remember that a remnant still remains. Out of prison, beyond the limits of Russian injunctions, out of reach of a deputy marshal’s club, above the throttling clutch of corporations and the enslaving power of plutocracy, out of range of the government’s machine guns and knowing the location of judicial traps and deadfalls, Americans may still indulge in the exaltation of liberty, though pursued through every lane and avenue of life by the baying hounds of usurped and unconstitutional power, glad if when night lets down her sable curtains, they are out of prison, though still the wage-slaves of a plutocracy which, were it in the celestial city, would wreck every avenue leading up to the throne of the Infinite by stealing the gold with which they are paved, and debauch Heaven’s supreme court to obtain a decision that the command “thou shalt not steal” is unconstitutional. . . .

. . .Above all, what is the duty of American workingmen whose liberties have been placed in peril? They are not hereditary bondsmen. Their fathers were free born—their sovereignty none denied and their children yet have the ballot. It has been called “a weapon that executes a free man’s will as lighting does the will of God.”2 It is a metaphor pregnant with life and truth. There is nothing in our government it cannot remove or amend. It can make and unmake presidents and congresses and courts. It can abolish unjust laws and consign to eternal odium and oblivion unjust judges, strip from them their robes and gowns and send them forth unclean as lepers to bear the burden of merited obloquy as Cain with the mark of a murderer. It can sweep away trusts, syndicates, corporations, monopolies, and every other abnormal development of the money power designed to abridge the liberties of workingmen and enslave them by the degradation incident to poverty and enforced idleness, as cyclones scatter the leaves of the forest. The ballot can do all this and more. It can give our civilization its crowning glory—the cooperative commonwealth. . . .

In the great Pullman strike the American Railway Union challenged the power of corporations in a way that had not previously been done, and the analyzation of this fact serves to expand it to proportions that the most conservative men of the nation regard with alarm. It must be borne in mind that the American Railway Union did not challenge the government. It threw down no gauntlet to courts or armies—it simply resisted the invasion of the rights of workingmen by corporations. It challenged and defied the power of corporations. Thrice armed with a just cause, the organization believed that justice would win for labor a notable victory, and the records proclaim that its confidence was not misplaced.

The corporations, left to their own resources of money, mendacity, and malice, of thugs and ex-convicts, leeches and lawyers, would have been overwhelmed with defeat and the banners of organized labor would have floated triumphant in the breeze.

This the corporations saw and believed—hence the crowning act of infamy in which the federal courts and the federal armies participated, and which culminated in the defeat of labor. . . .

. . .[T]he defeat of the American Railway Union involved questions of law, constitution and government which, all things considered, are without a parallel in court and governmental proceedings under the Constitution of the Republic. And it is this judicial and administrative usurpation of power to override the rights of states and strike down the liberties of the people that has conferred upon the incidents connected with the Pullman strike such commanding importance as to attract the attention of men of the highest attainments in constitutional law and of statesmen who, like Jefferson, view with alarm the processes by which the Republic is being wrecked and a despotism reared upon its ruins. . . .

From such reflections I turn to the practical lessons taught by this “Liberation Day” demonstration. It means that American lovers of liberty are setting in operation forces to rescue their constitutional liberties from the grasp of monopoly and its mercenary hirelings. It means that the people are aroused in view of impending perils and that agitation, organization, and unification are to be the future battle cries of men who will not part with their birthrights and, like Patrick Henry, will have the courage to exclaim: “Give me liberty or give me death!” I have borne with such composure as I could command the imprisonment which deprived me of my liberty. Were I a criminal; were I guilty of crimes meriting a prison cell; had I ever lifted my hand against the life or the liberty of my fellow men; had I ever sought to filch their good name, I would not be here. I would have fled from the haunts of civilization and taken up my residence in some cave where the voice of my kindred is never heard. But I am standing here without a self-accusation of crime or criminal intent festering in my conscience, in the sunlight once more, among my fellow men, contributing as best I can to make this “Liberation Day” from Wood- stock prison a memorial day, realizing that, as Lowell sang:

He’s true to God who’s true to man; wherever wrong is done,

To the humblest and the weakest, ’neath the all-beholding sun.

That wrong is also done to us, and they are slaves most base,

Whose love of right is for themselves and not for all their race.3

Annual Message to Congress (1895)

December 03, 1895

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.