No related resources

Introduction

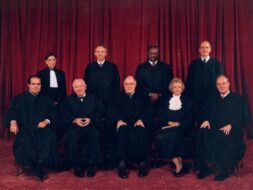

In Regents of University of California v. Bakke (1978), the U.S. Supreme Court addressed for the first time the issue of racial classifications in university admissions. The Court there ruled unlawful a University of California–Davis admissions program that reserved sixteen out of one hundred seats in the first-year medical school class for members of putatively disadvantaged racial or ethnic minority groups. The Bakke ruling’s precedential value remained unclear, however, because none of his colleagues subscribed to the reasoning in Justice Lewis Powell’s opinion for the Court. Clarification of the Court’s position on the issue arrived only twenty-five years later in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003).

Plaintiff Barbara Grutter, then a forty-three-year-old mother of two, was denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School in 1996. Upon learning that her numerical qualifications (undergraduate grade-point averages and aptitude test scores) were superior to those of some successful applicants, she brought suit, alleging that the university had unlawfully discriminated against her based on her racial identity as a white woman. The issue before the Court was whether the university’s professed interest in diversifying its student body—in particular by the preferential admission of members of selected, historically underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups—carried more constitutional weight than Grutter’s claim to equal treatment under the law irrespective of racial or ethnic identity.

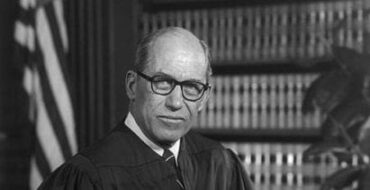

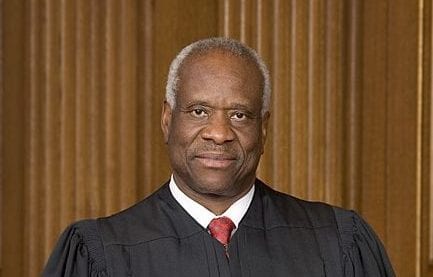

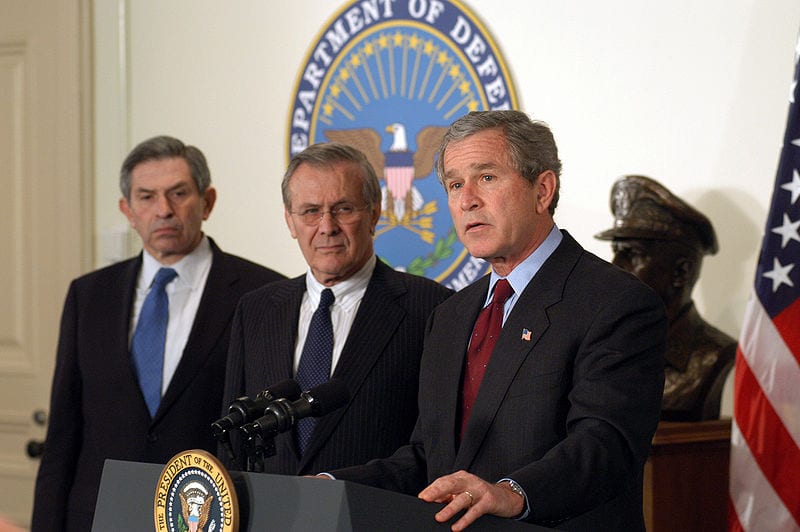

Lee Bollinger, at the time the president of the University of Michigan, was the defendant in the case. The Court decided in Bollinger’s favor 5–4, with various justices writing concurring and dissenting opinions that other justices joined. The opinions of Justice O’Connor, writing for the majority, and Justice Thomas, in dissent, are excerpted below.

Source: 539 U.S. 306 (2003); available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/02-241.ZS.html. Unless otherwise noted, all references are from the opinions of Justices O’Connor and Thomas.

JUSTICE O’CONNOR delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case requires us to decide whether the use of race as a factor in student admissions by the University of Michigan Law School (Law School) is unlawful. . . .

. . .Today, we hold that the Law School has a compelling interest in attaining a diverse student body. . . .

As part of its goal of “assembling a class that is both exceptionally academically qualified and broadly diverse,” the Law School seeks to “enroll a ‘critical mass’ of minority students.” The Law School’s interest is not simply “to assure within its student body some specified percentage of a particular group merely because of its race or ethnic origin.”1 That would amount to outright racial balancing, which is patently unconstitutional. Rather, the Law School’s concept of critical mass is defined by reference to the educational benefits that diversity is designed to produce. . . .

We have repeatedly acknowledged the overriding importance of preparing students for work and citizenship. This Court has long recognized that “education . . . is the very foundation of good citizenship.”2 For this reason, the diffusion of knowledge and opportunity through public institutions of higher education must be accessible to all individuals regardless of race or ethnicity. Effective participation by members of all racial and ethnic groups in the civic life of our nation is essential if the dream of one nation, indivisible, is to be realized. . . .

In order to cultivate a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, it is necessary that the path to leadership be visibly open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity. All members of our heterogeneous society must have confidence in the openness and integrity of the educational institutions that provide this training. . . .Access to legal education (and thus the legal profession) must be inclusive of talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity, so that all members of our heterogeneous society may participate in the educational institutions that provide the training and education necessary to succeed in America. . . .

. . .As Justice Powell made clear in Bakke, truly individualized consideration demands that race be used in a flexible, nonmechanical way. It follows from this mandate that universities cannot establish quotas for members of certain racial groups or put members of those groups on separate admissions tracks. Nor can universities insulate applicants who belong to certain racial or ethnic groups from the competition for admission. Universities can, however, consider race or ethnicity more flexibly as a “plus” factor in the context of individualized consideration of each and every applicant. . . .

Justice Powell’s distinction between the medical school’s rigid sixteen-seat quota and Harvard’s flexible use of race as a “plus” factor is instructive. Harvard certainly had minimum goals for minority enrollment, even if it had no specific number firmly in mind. . . . What is more, Justice Powell flatly rejected the argument that Harvard’s program was “the functional equivalent of a quota” merely because it had some “plus” for race, or gave greater “weight” to race than to some other factors, in order to achieve student body diversity.3…

What is more, the Law School actually gives substantial weight to diversity factors besides race. The Law School frequently accepts nonminority applicants with grades and test scores lower than underrepresented minority applicants (and other nonminority applicants) who are rejected. This shows that the Law School seriously weighs many other diversity factors besides race that can make a real and dispositive difference for nonminority applicants as well. By this flexible approach, the Law School sufficiently takes into account, in practice as well as in theory, a wide variety of characteristics besides race and ethnicity that contribute to a diverse student body. . . .

We are mindful, however, that “[a] core purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to do away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race.”4 Accordingly, race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time. This requirement reflects that racial classifications, however compelling their goals, are potentially so dangerous that they may be employed no more broadly than the interest demands. Enshrining a permanent justification for racial preferences would offend this fundamental equal protection principle. We see no reason to exempt race-conscious admissions programs from the requirement that all governmental use of race must have a logical end point. . . .

. . .It has been twenty-five years since Justice Powell first approved the use of race to further an interest in student body diversity in the context of public higher education. Since that time, the number of minority applicants with high grades and test scores has indeed increased. We expect that twenty-five years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.

JUSTICE THOMAS, with whom JUSTICE SCALIA joins as to Parts I–VII, concurring in part and dissenting in part.

Frederick Douglass, speaking to a group of abolitionists almost 140 years ago, delivered a message lost on today’s majority:

[I]n regard to the colored people, there is always more that is benevolent, I perceive, than just, manifested toward us. What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us. . . .I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall!. . .And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!. . .[Y]our interference is doing him positive injury.5

Like Douglass, I believe blacks can achieve in every avenue of American life without the meddling of university administrators. Because I wish to see all students succeed whatever their color, I share, in some respect, the sympathies of those who sponsor the type of discrimination advanced by the University of Michigan Law School. The Constitution does not, however, tolerate institutional devotion to the status quo in admissions policies when such devotion ripens into racial discrimination. . . .

. . .I agree with the Court’s holding that racial discrimination in higher education admissions will be illegal in twenty-five years. . . .I respectfully dissent from the remainder of the Court’s opinion and the judgment, however, because I believe that the Law School’s current use of race violates the equal protection clause and that the Constitution means the same thing today as it will in three hundred months. . . .

The Constitution abhors classifications based on race, not only because those classifications can harm favored races or are based on illegitimate motives, but also because every time the government places citizens on racial registers and makes race relevant to the provision of burdens or benefits, it demeans us all. . . .

. . .I believe what lies beneath the Court’s decision today are the benighted notions that one can tell when racial discrimination benefits (rather than hurts) minority groups and that racial discrimination is necessary to remedy general societal ills. This Court’s precedents supposedly settled both issues, but clearly the majority still cannot commit to the principle that racial classifications are per se harmful and that almost no amount of benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify such classifications.

Putting aside what I take to be the Court’s implicit rejection of Adarand’s holding6 that beneficial and burdensome racial classifications are equally invalid, I must contest the notion that the Law School’s discrimination benefits those admitted as a result of it. . . .[N]owhere in any of the filings in this Court is any evidence that the purported “beneficiaries” of this racial discrimination prove themselves by performing at (or even near) the same level as those students who receive no preferences. . . .

The Law School tantalizes unprepared students with the promise of a University of Michigan degree and all of the opportunities that it offers. These overmatched students take the bait, only to find that they cannot succeed in the cauldron of competition. And this mismatch crisis is not restricted to elite institutions. . . . While these students may graduate with law degrees, there is no evidence that they have received a qualitatively better legal education or become better lawyers) than if they had gone to a less “elite” law school for which they were better prepared. . . .

It is uncontested that each year, the Law School admits a handful of blacks who would be admitted in the absence of racial discrimination. Who can differentiate between those who belong and those who do not? The majority of blacks are admitted to the Law School because of discrimination, and because of this policy all are tarred as undeserving. This problem of stigma does not depend on determinacy as to whether those stigmatized are actually the “beneficiaries” of racial discrimination. When blacks take positions in the highest places of government, industry, or academia, it is an open question today whether their skin color played a part in their advancement. The question itself is the stigma—because either racial discrimination did play a role, in which case the person may be deemed “otherwise unqualified,” or it did not, in which case asking the question itself unfairly marks those blacks who would succeed without discrimination. . . .

For the immediate future . . . the majority has placed its imprimatur on a practice that can only weaken the principle of equality embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the equal protection clause. “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”7 It has been nearly 140 years since Frederick Douglass asked the intellectual ancestors of the Law School to “[d]o nothing with us!” and the nation adopted the Fourteenth Amendment. Now we must wait another twenty-five years to see this principle of equality vindicated. I therefore respectfully dissent from the remainder of the Court’s opinion and the judgment.

- 1. Regents of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), at 307.

- 2. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), at 493.

- 3. Regents v. Bakke, at 317–18.

- 4. Palmore v. Sidoti, 466 U.S. 429 (1984), at 432.

- 5. “What the Black Man Wants”: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 26, 1865, reprinted in The Frederick Douglass Papers 59, 68 (ed. J. Blassingame and J. McKivigan, 1991).

- 6. In Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña (1995), the Court held that use of racial classifications by the federal government must meet strict scrutiny, the highest level of judicial scrutiny. By this standard, any racial classification must be narrowly tailored to meet a compelling government interest.

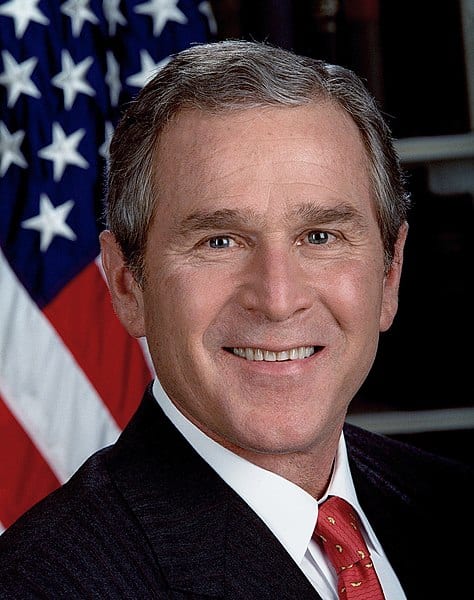

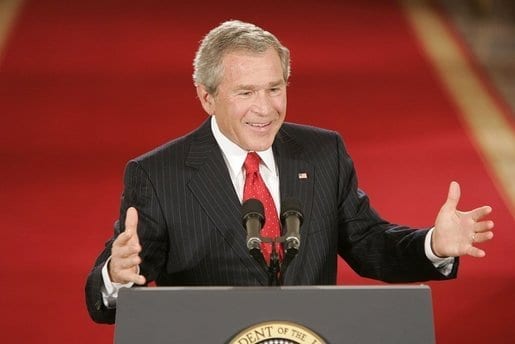

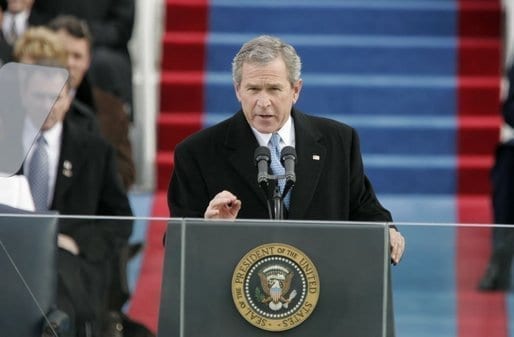

President Bush speaks at Goree Island

July 08, 2003

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.