No related resources

Introduction

The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 was designed to encourage consistency in federal sentencing by replacing the broad sentencing discretion of judges with mandatory guidelines. The act created the U.S. Sentencing Commission, an independent commission within the judicial branch composed of seven voting members. At least three members were to be federal judges selected by the president. The commission was required to have a bipartisan membership, and the voting members served six-year terms. Committee members were subject to removal by the president “only for neglect of duty or malfeasance in office or for other good cause shown.” The commission was charged with developing the sentencing guidelines on the basis of criteria outlined in the act. Judges who deviated from the guidelines would have to explain their reasons for doing so, and their decisions would be subject to appeal. John Mistretta was charged with trafficking cocaine and sentenced under the new guidelines. Mistretta challenged his conviction, arguing that the commission that created the guidelines violated both the nondelegation doctrine (the doctrine that Congress cannot delegate its legislative powers to others) and the separation of powers.

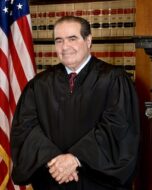

Like Morrison v. Olson, Mistretta constitutes a landmark decision regarding the separation of powers in the modern era. Justice Harry Blackmun (1908–1999) did note the unprecedented nature of the commission within our structure of government, but he concluded that the commission did not violate the separation of powers because none of its provisions “unduly commingle the three branches of government” despite their novel design. In his dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) argued that the Court’s decision upholding the Sentencing Commission constituted yet another ill-conceived break from our constitutional principles that would have negative consequences for both the rule of law and the separation of powers.

488 U.S. 361 (1989), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/488/361/.

Justice Blackmun delivered the opinion of the Court. . . .

Nondelegation Doctrine

Petitioner1 argues that in delegating the power to promulgate sentencing guidelines for every federal criminal offense to an independent Sentencing Commission, Congress has granted the Commission excessive legislative discretion in violation of the constitutionally based nondelegation doctrine. We do not agree.

The nondelegation doctrine is rooted in the principle of separation of powers that underlies our tripartite system of government. The Constitution provides that “[a]ll legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States,” and we long have insisted that “the integrity and maintenance of the system of government ordained by the Constitution” mandate that Congress generally cannot delegate its legislative power to another branch. We also have recognized, however, that the separation-of-powers principle, and the nondelegation doctrine in particular, do not prevent Congress from obtaining the assistance of its coordinate branches. . . . So long as Congress “shall lay down by legislative act an intelligible principle to which the person or body authorized to [exercise the delegated authority] is directed to conform, such legislative action is not a forbidden delegation of legislative power.”2

Applying this “intelligible principle” test to congressional delegations, our jurisprudence has been driven by a practical understanding that in our increasingly complex society, replete with ever changing and more technical problems, Congress simply cannot do its job absent an ability to delegate power under broad general directives. . . .Accordingly, this Court has deemed it “constitutionally sufficient if Congress clearly delineates the general policy, the public agency which is to apply it, and the boundaries of this delegated authority.”3…

Developing proportionate penalties for hundreds of different crimes by a virtually limitless array of offenders is precisely the sort of intricate, labor-intensive task for which delegation to an expert body is especially appropriate. . . .

Separation of Powers

Having determined that Congress has set forth sufficient standards for the exercise of the Commission’s delegated authority, we turn to Mistretta’s claim that the act violates the constitutional principle of separation of powers. . . .

Mistretta . . . argues that Congress, in constituting the Commission as it did, effected an unconstitutional accumulation of power within the judicial branch while at the same time undermining the judiciary’s independence and integrity. Specifically, petitioner claims that in delegating to an independent agency within the judicial branch the power to promulgate sentencing guidelines, Congress unconstitutionally has required the branch, and individual Article III judges,4 to exercise not only their judicial authority, but legislative authority—the making of sentencing policy—as well. Such rule-making authority, petitioner contends, may be exercised by Congress, or delegated by Congress to the executive, but may not be delegated to or exercised by the judiciary.

At the same time, petitioner asserts, Congress unconstitutionally eroded the integrity and independence of the judiciary by requiring Article III judges to sit on the Commission, by requiring that those judges share their rulemaking authority with nonjudges, and by subjecting the Commission’s members to appointment and removal by the president. According to petitioner, Congress, consistent with the separation of powers, may not upset the balance among the branches by coopting federal judges into the quintessentially political work of establishing sentencing guidelines, by subjecting those judges to the political whims of the chief executive, and by forcing judges to share their power with nonjudges. . . .

Location of the Commission

The Sentencing Commission unquestionably is a peculiar institution within the framework of our government. Although placed by the act in the judicial branch, it is not a court and does not exercise judicial power. Rather, the Commission is an “independent” body comprised of seven voting members including at least three federal judges, entrusted by Congress with the primary task of promulgating sentencing guidelines. Our constitutional principles of separated powers are not violated, however, by mere anomaly or innovation. . . .Congress’ decision to create an independent rule-making body to promulgate sentencing guidelines and to locate that body within the judicial branch is not unconstitutional unless Congress has vested in the Commission powers that are more appropriately performed by the other branches or that undermine the integrity of the judiciary. . . .

Given the consistent responsibility of federal judges to pronounce sentence within the statutory range established by Congress, we find that the role of the Commission in promulgating guidelines for the exercise of that judicial function bears considerable similarity to the role of this Court in establishing rules of procedure under the various enabling Acts. Such guidelines, like the Federal Rules of Criminal and Civil Procedure, are court rules—rules. . . for carrying into execution judgments that the judiciary has the power to pronounce. . . .

Composition of the Commission

We now turn to petitioner’s claim that Congress’ decision to require at least three federal judges to serve on the Commission and to require those judges to share their authority with nonjudges undermines the integrity of the judicial branch. . . .

The text of the Constitution contains no prohibition against the service of active federal judges on independent commissions such as that established by the act. . . .

Our inferential reading that the Constitution does not prohibit Article III judges from undertaking extrajudicial duties finds support in the historical practice of the Founders after ratification. . . .

. . . We conclude that the principle of separation of powers does not absolutely prohibit Article III judges from serving on commissions such as that created by the act. The judges serve on the Sentencing Commission not pursuant to their status and authority as Article III judges, but solely because of their appointment by the president as the act directs. Such power as these judges wield as commissioners is not judicial power; it is administrative power derived from the enabling legislation. Just as the nonjudicial members of the Commission act as administrators, bringing their experience and wisdom to bear on the problems of sentencing disparity, so too the judges, uniquely qualified on the subject of sentencing, assume a wholly administrative role upon entering into the deliberations of the Commission. In other words, the Constitution, at least as a per se matter,5 does not forbid judges to wear two hats; it merely forbids them to wear both hats at the same time. . . .

Justice Scalia, dissenting.

While the products of the Sentencing Commission’s labors have been given the modest name “Guidelines,” they have the force and effect of laws, prescribing the sentences criminal defendants are to receive. A judge who disregards them will be reversed. I dissent from today’s decision because I can find no place within our constitutional system for an agency created by Congress to exercise no governmental power other than the making of laws. . . .

The focus of controversy, in the long line of our so-called excessive delegation cases, has been whether the degree of generality contained in the authorization for exercise of executive or judicial powers in a particular field is so unacceptably high as to amount to a delegation of legislative powers. I say “so-called excessive delegation” because although that convenient terminology is often used, what is really at issue is whether there has been any delegation of legislative power, which occurs (rarely) when Congress authorizes the exercise of executive or judicial power without adequate standards. Strictly speaking, there is no acceptable delegation of legislative power. As John Locke put it almost three hundred years ago, “[t]he power of the legislative being derived from the people by a positive voluntary grant and institution, can be no other, than what the positive grant conveyed, which being only to make laws, and not to make legislators, the legislative can have no power to transfer their authority of making laws, and place it in other hands.”6 Or as we have less epigrammatically said: “That Congress cannot delegate legislative power to the president is a principle universally recognized as vital to the integrity and maintenance of the system of government ordained by the Constitution.”7…

The delegation of lawmaking authority to the Commission is, in short, unsupported by any legitimating theory to explain why it is not a delegation of legislative power. To disregard structural legitimacy is wrong in itself—but since structure has purpose, the disregard also has adverse practical consequences. In this case, as suggested earlier, the consequence is to facilitate and encourage judicially uncontrollable delegation. . . .

By reason of today’s decision, I anticipate that Congress will find delegation of its lawmaking powers much more attractive in the future. If rulemaking can be entirely unrelated to the exercise of judicial or executive powers, I foresee all manner of “expert” bodies, insulated from the political process, to which Congress will delegate various portions of its lawmaking responsibility. How tempting to create an expert Medical Commission (mostly M.D.s, with perhaps a few Ph.D.s in moral philosophy) to dispose of such thorny, “no-win” political issues as the withholding of life-support systems in federally funded hospitals, or the use of fetal tissue for research. This is an undemocratic precedent that we set—not because of the scope of the delegated power, but because its recipient is not one of the three branches of government. The only governmental power the Commission possesses is the power to make law; and it is not the Congress. . . .

Today’s decision follows the regrettable tendency of our recent separation-of-powers jurisprudence to treat the Constitution as though it were no more than a generalized prescription that the functions of the branches should not be commingled too much—how much is too much to be determined, case-by-case, by this Court. The Constitution is not that. Rather, as its name suggests, it is a prescribed structure, a framework, for the conduct of government. In designing that structure, the Framers themselves considered how much commingling was, in the generality of things, acceptable, and set forth their conclusions in the document. . . .

I think the Court errs, in other words, not so much because it mistakes the degree of commingling, but because it fails to recognize that this case is not about commingling, but about the creation of a new branch altogether, a sort of junior-varsity Congress. It may well be that in some circumstances such a branch would be desirable; perhaps the agency before us here will prove to be so. But there are many desirable dispositions that do not accord with the constitutional structure we live under. And in the long run the improvisation of a constitutional structure on the basis of currently perceived utility will be disastrous.

- 1. The petitioner is someone appealing a case to a higher court.

- 2. Justice Blackmun’s note: J. W. Hampton, Jr., & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394, 276 U.S. 409 (1928).

- 3. Justice Blackmun’s note: American Power & Light Co. v. SEC, 329 U.S. 90, 329 U.S. 105 (1946).

- 4. Judges appointed under Article III of the Constitution.

- 5. By or in itself.

- 6. Justice Scalia’s note: J. Locke, Second Treatise of Government 87 (R. Cox ed. 1982) (emphasis added).

- 7. Justice Scalia’s note: Field v. Clark, supra, at 143 U.S. 692.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.