No related resources

Introduction

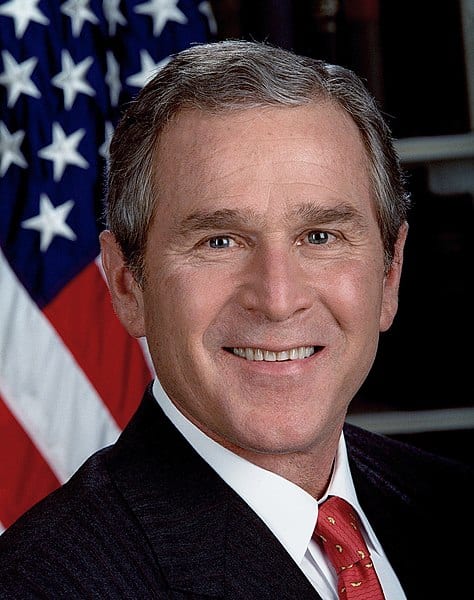

In this 2001 lecture, Sonia Sotomayor (1954–), then a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, addressed the status of women and minorities on the bench. The speech attracted little attention at the time, but it became a source of controversy after President Obama nominated her to the Supreme Court in 2009.

In the speech, Sotomayor directly disagreed with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor that wise judges will reach the same conclusion regardless of their sex. But most controversially, she went on to claim: “I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.” Few objected to Sotomayor’s claim that a judge’s life experiences will affect how they do their job, but her assertion that people of a certain race and sex would make better judges struck some as a claim that certain groups are inherently superior to others and was therefore racist and sexist. At her nomination hearing she retreated from this stance, telling the Senate Judiciary Committee “I want to state up front, unequivocally and without doubt: I do not believe that any ethnic, racial, or gender group has an advantage in sound judging. I do believe every person has an equal opportunity to be a good and wise judge, regardless of their background or life experience.” Even though she later qualified her claim, this speech clearly articulated the idea that the race and sex of judges matter for judicial decision making and thus should matter for the composition of the federal courts—a stance made all the more important given her status as the nation’s first Hispanic justice.

Source: Judge Sonia Sotomayor, “A Latina Judge’s Voice,” Berkeley La Raza Law Journal 13, no. 1 (2002): 87–93, https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1118136?ln=en.

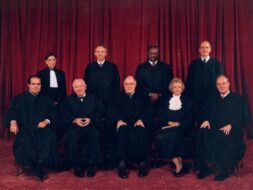

. . .I was born in the year 1954. That year was the fateful year in which Brown v. Board of Education was decided. When I was eight, in 1961, the first Latino, the wonderful Judge Reynaldo Garza, was appointed to the federal bench, an event we are celebrating at this conference. When I finished law school in 1979, there were no women judges on the Supreme Court or on the highest court of my home state, New York. There was then only one Afro-American Supreme Court justice, and then and now no Latino or Latina justices on our highest court. Now in the last twenty plus years of my professional life, I have seen a quantum leap in the representation of women and Latinos in the legal profession and particularly in the judiciary. In addition to the appointment of the first female United States attorney general, Janet Reno, we have seen the appointment of two female justices to the Supreme Court and two female justices to the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court of my home state. One of those judges is the chief judge and the other is a Puerto Riqueña, like I am. As of today, women sit on the highest courts of almost all of the states and of the territories, including Puerto Rico. One supreme court, that of Minnesota, had a majority of women justices for a period of time.

As of September 1, 2001, the federal judiciary consisting of Supreme, circuit, and district court judges was about 22 percent women. In 1992, nearly ten years ago, when I was first appointed a district court judge, the percentage of women in the total federal judiciary was only 13 percent. Now, the growth of Latino representation is somewhat less favorable. As of today we have, as I noted earlier, no Supreme Court justices, and we have only 10 out of 147 active circuit court judges, and 30 out of 587 active district court judges. Those numbers are grossly below our proportion of the population. As recently as 1965, however, the federal bench had only three women serving and only one Latino judge. So changes are happening, although in some areas, very slowly. These figures and appointments are heartwarming. Nevertheless, much still remains to happen.

Let us not forget that between the appointments of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 1981 and Justice Ginsburg in 1992, eleven years passed. Similarly, between Justice Kaye’s initial appointment as an associate judge to the New York Court of Appeals in 1983, and Justice Ciparick’s appointment in 1993, ten years elapsed.1 Almost nine years later, we are waiting for a third appointment of a woman to both the Supreme Court and the New York Court of Appeals and of a second minority, male or female, preferably Hispanic, to the Supreme Court. In 1992 when I joined the bench, there were still two out of 13 circuit courts and about 53 out of 92 district courts in which no women sat. At the beginning of September of 2001, there are women sitting in all 13 circuit courts. The First, Fifth, Eighth, and Federal Circuits each have only 1 female judge, however, out of a combined total number of 48 judges. There are still nearly 37 district courts with no women judges at all. For women of color the statistics are more sobering. As of September 20, 1998, of the then 195 circuit court judges only 2 were African American women and two Hispanic women. Of the 641 district court judges only 12 were African American women and 11 Hispanic women. African American women comprise only 1.56 percent of the federal judiciary and Hispanic American women comprise only 1 percent. No African American, male or female, sits today on the Fourth or Federal Circuits. And no Hispanics, male or female, sit on the Fourth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, District of Columbia, or Federal Circuits.

Sort of shocking, isn’t it? This is the year 2002. We have a long way to go. Unfortunately, there are some very deep storm warnings we must keep in mind. In at least the last five years the majority of nominated judges the Senate delayed more than one year before confirming or never confirming were women or minorities. I need not remind this audience that Judge Paez2 of your home circuit, the Ninth Circuit, has had the dubious distinction of having had his confirmation delayed the longest in Senate history. These figures demonstrate that there is a real and continuing need for Latino and Latina organizations and community groups throughout the country to exist and to continue their efforts of promoting women and men of all colors in their pursuit for equality in the judicial system.

This weekend’s conference, illustrated by its name, is bound to examine issues that I hope will identify the efforts and solutions that will assist our communities. The focus of my speech tonight, however, is not about the struggle to get us where we are and where we need to go but instead to discuss with you what it all will mean to have more women and people of color on the bench. The statistics I have been talking about provide a base from which to discuss a question which one of my former colleagues on the Southern District bench, Judge Miriam Cedarbaum,3 raised when speaking about women on the federal bench. Her question was: What do the history and statistics mean? In her speech, Judge Cedarbaum expressed her belief that the number of women and by direct inference people of color on the bench, was still statistically insignificant and that therefore we could not draw valid scientific conclusions from the acts of so few people over such a short period of time. Yet, we do have women and people of color in more significant numbers on the bench, and no one can or should ignore pondering what that will mean or not mean in the development of the law. Now, I cannot and do not claim this issue as personally my own. In recent years there has been an explosion of research and writing in this area. On one of the panels tomorrow, you will hear the Latino perspective in this debate.

For those of you interested in the gender perspective on this issue, I commend to you a wonderful compilation of articles published on the subject in volume 77 of Judicature, the journal of the American Judicature Society, of November–December 1993. It is on Westlaw/Lexis, and I assume the students and academics in this room can find it.

Now Judge Cedarbaum expresses concern with any analysis of women and presumably again people of color on the bench, which begins and presumably ends with the conclusion that women or minorities are different from men generally. She sees danger in presuming that judging should be gender or anything else based. She rightly points out that the perception of the differences between men and women is what led to many paternalistic laws and to the denial to women of the right to vote because we were described then “as not capable of reasoning or thinking logically” but instead of “acting intuitively.” I am quoting adjectives that were bandied around famously during the suffragettes’ movement.

While recognizing the potential effect of individual experiences on perception, Judge Cedarbaum nevertheless believes that judges must transcend their personal sympathies and prejudices and aspire to achieve a greater degree of fairness and integrity based on the reason of law. Although I agree with and attempt to work toward Judge Cedarbaum’s aspiration, I wonder whether achieving that goal is possible in all or even in most cases. And I wonder whether by ignoring our differences as women or men of color we do a disservice both to the law and society. Whatever the reasons why we may have different perspectives, either as some theorists suggest because of our cultural experiences or as others postulate because we have basic differences in logic and reasoning, are in many respects a small part of a larger practical question we as women and minority judges in society in general must address. I accept the thesis of a law school classmate, Professor Steven Carter of Yale Law School, in his affirmative action book that in any group of human beings there is a diversity of opinion because there is both a diversity of experiences and of thought. Thus, as noted by another Yale Law School professor—I did graduate from there and I am not really biased except that they seem to be doing a lot of writing in that area—Professor Judith Resnik says that there is not a single voice of feminism, not a feminist approach but many who are exploring the possible ways of being that are distinct from those structured in a world dominated by the power and words of men. Thus, feminist theories of judging are in the midst of creation and are not and perhaps will never aspire to be as solidified as the established legal doctrines of judging can sometimes appear to be.

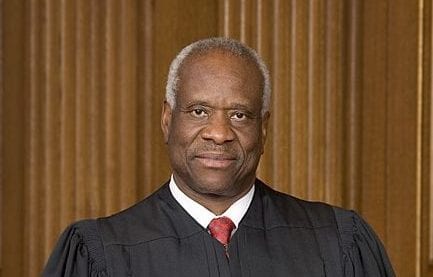

That same point can be made with respect to people of color. No one person, judge, or nominee will speak in a female or people of color voice. I need not remind you that Justice Clarence Thomas4 represents a part but not the whole of African American thought on many subjects. Yet, because I accept the proposition that, as Judge Resnik describes it, “to judge is an exercise of power” and because as, another former law school classmate, Professor Martha Minnow of Harvard Law School, states “there is no objective stance but only a series of perspectives—no neutrality, no escape from choice in judging,” I further accept that our experiences as women and people of color affect our decisions. The aspiration to impartiality is just that—it’s an aspiration because it denies the fact that we are by our experiences making different choices than others. Not all women or people of color, in all or some circumstances or indeed in any particular case or circumstance but enough people of color in enough cases, will make a difference in the process of judging. The Minnesota Supreme Court has given an example of this. As reported by Judge Patricia Wald, formerly of the D.C. Circuit Court, three women on the Minnesota court with two men dissenting agreed to grant a protective order against a father’s visitation rights when the father abused his child. The Judicature journal has at least two excellent studies on how women on the courts of appeal and state supreme courts have tended to vote more often than their male counterpart to uphold women’s claims in sex discrimination cases and criminal defendants’ claims in search-and-seizure cases. As recognized by legal scholars, whatever the reason, not one woman or person of color in any one position but as a group we will have an effect on the development of the law and on judging.

In our private conversations, Judge Cedarbaum has pointed out to me that seminal decisions in race and sex discrimination cases have come from Supreme Courts composed exclusively of white males. I agree that this is significant, but I also choose to emphasize that the people who argued those cases before the Supreme Court which changed the legal landscape ultimately were largely people of color and women. I recall that Justice Thurgood Marshall,5 Judge Connie Baker Motley,6 the first black woman appointed to the federal bench, and others of the NAACP argued Brown v. Board of Education. Similarly, Justice Ginsburg,7 with other women attorneys, was instrumental in advocating and convincing the Court that equality of work required equality in terms and conditions of employment.

Whether born from experience or inherent physiological or cultural differences, a possibility I abhor less or discount less than my colleague Judge Cedarbaum, our gender and national origins may and will make a difference in our judging. Justice O’Connor8 has often been cited as saying that a wise old man and wise old woman will reach the same conclusion in deciding cases. I am not so sure Justice O’Connor is the author of that line since Professor Resnik attributes that line to Supreme Court Justice Coyle. I am also not so sure that I agree with the statement. First, as Professor Martha Minnow has noted, there can never be a universal definition of wise. Second, I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.

Let us not forget that wise men like Oliver Wendell Holmes and Justice Cardozo9 voted on cases which upheld both sex and race discrimination in our society. Until 1972, no Supreme Court case ever upheld the claim of a woman in a gender discrimination case. I, like Professor Carter, believe that we should not be so myopic as to believe that others of different experiences or backgrounds are incapable of understanding the values and needs of people from a different group. Many are so capable. As Judge Cedarbaum pointed out to me, nine white men on the Supreme Court in the past have done so on many occasions and on many issues, including Brown.

However, to understand takes time and effort, something that not all people are willing to give. For others, their experiences limit their ability to understand the experiences of others. Others simply do not care. Hence, one must accept the proposition that a difference there will be by the presence of women and people of color on the bench. Personal experiences affect the facts that judges choose to see. My hope is that I will take the good from my experiences and extrapolate them further into areas with which I am unfamiliar. I simply do not know exactly what that difference will be in my judging. But I accept there will be some based on my gender and my Latina heritage.

I also hope that by raising the question today of what difference having more Latinos and Latinas on the bench will make will start your own evaluation. For people of color and women lawyers, what does and should being an ethnic minority mean in your lawyering? For men lawyers, what areas in your experiences and attitudes do you need to work on to make you capable of reaching those great moments of enlightenment which other men in different circumstances have been able to reach? For all of us, how do we change the facts that in every task force study of gender and race bias in the courts, women and people of color, lawyers and judges alike, report in significantly higher percentages than white men that their gender and race have shaped their careers, from hiring, retention, to promotion, and that a statistically significant number of women and minority lawyers and judges, both alike, have experienced bias in the courtroom?

Each day on the bench I learn something new about the judicial process and about being a professional Latina woman in a world that sometimes looks at me with suspicion. I am reminded each day that I render decisions that affect people concretely and that I owe them constant and complete vigilance in checking my assumptions, presumptions, and perspectives and ensuring that to the extent that my limited abilities and capabilities permit me, that I reevaluate them and change as circumstances and cases before me require. I can and do aspire to be greater than the sum total of my experiences, but I accept my limitations. I willingly accept that we who judge must not deny the differences resulting from experience and heritage but attempt, as the Supreme Court suggests, continuously to judge when those opinions, sympathies, and prejudices are appropriate.

There is always a danger embedded in relative morality, but since judging is a series of choices that we must make, that I am forced to make, I hope that I can make them by informing myself on the questions I must not avoid asking and continuously pondering. We, I mean all of us in this room, must continue individually and in voices united in organizations that have supported this conference, to think about these questions and to figure out how we go about creating the opportunity for there to be more women and people of color on the bench so we can finally have statistically significant numbers to measure the differences we will and are making.

- 1. Justice Judith Ann Kaye (1938–2016) became chief justice of the Court of Appeals, the highest judicial position in New York, in 1993 and served in that position until 2008. Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick (1942– ) was an associate justice on the New York Court of Appeals from 1994 to 2012.

- 2. Richard Anthony Paez (1947–) served as an associate justice on the Ninth Circuit from 2000 to 2021.

- 3. Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum (1929–2016) was a judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

- 4. Missouri v. Jenkins

- 5. “The Sword and the Robe”

- 6. Constance Baker Motley (1921–2005) was a judge and then chief judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

- 7. “Speaking in a Judicial Voice”

- 8. “Portia’s Progress”

- 9. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court, as was Benjamin Cardozo (1870–1938).

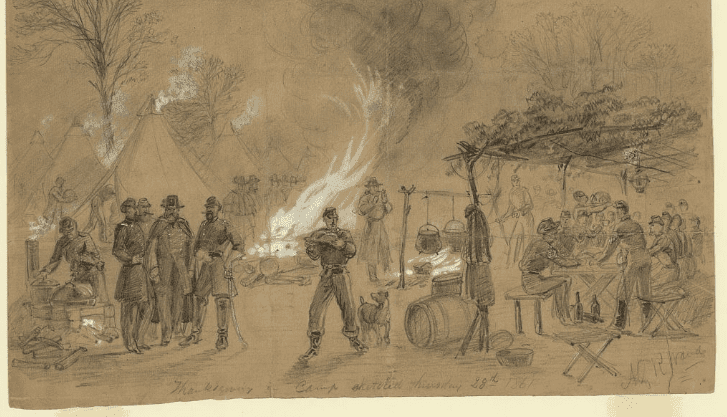

Thanksgiving Proclamation (2001)

November 16, 2001

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.