The Judiciary

No court exercises more political power within its political order than the U.S. Supreme Court.

No court exercises more power than the Supreme Court of the United States. That is not because it is the highest court of the most powerful nation in the world—although it is. Instead, it is because no court exercises more political power within its political order than the U.S. Supreme Court. The reason is, of course, the power of judicial review, or perhaps more accurately judicial supremacy, the idea that the Supreme Court is the final interpreter of the Constitution. It is important to distinguish between judicial review and judicial supremacy. Judicial review as initially conceived was a limited power that allowed the Court to avoid being controlled by what it regarded as the unconstitutional decisions of other branches. Properly read, this is the argument of Chief Justice Marshall in Marbury v. Madison. But this power did not extend to control over other branches. It did not allow the Court to dictate to other branches the limits of their constitutional powers. Judicial review eventually came to mean judicial supremacy, the notion that the Supreme Court is the ultimate and final interpreter of the Constitution and can indeed tell the other branches what they can and cannot do constitutionally. This power has always rested uneasily with principles of self-government. The most common attempt to defend judicial review contends that ratifying the Constitution was the most important act of self-government by the American people. Thus, when the Court strikes down a law as unconstitutional, it is defending the first act of self-government by the people.

But even if one accepts this defense of judicial review, other questions arise. Why should the Supreme Court be the final interpreter of the Constitution? The Constitution does not say that the Supreme Court is the guardian of the Constitution. In fact, the Constitution requires that the president and senators and representatives, as well as the members of the state legislatures and state executive and judicial officers, must also take an oath to uphold the Constitution (Article II, section 1; Article VI). Thus, through its structure of separation of powers and the duties it imposes on all the branches, one could argue that all three branches of the federal government have both the power and the duty to interpret the Constitution, an idea known as departmentalism. And if the Court is the supreme interpreter of the Constitution, does that not inherently make the decisions of the Court more important than the Constitution itself? As well, what guarantee is there that the Supreme Court will accurately interpret the document? And if the Court can impose its own preferences on the country under the guise of interpretation, does that also not implicitly empower the Court to amend the Constitution, undermining the constitutional authority of the people to do this through the amendment processes laid out in Article V?

Disputes over Supreme Court nominations over the past four decades have made these questions particularly salient. However, Americans have been debating them since before the Constitution was ratified. This volume presents many of the core documents surrounding this debate over the power of the Supreme Court and its role in American self-government. The Anti-Federalists found Article III, which created the Supreme Court and gave Congress the authority to create lower federal courts, deeply alarming. Brutus along with other Anti-Federalists predicted that even though the Constitution did not confer final interpretive authority on the Supreme Court, that would nevertheless become the accepted practice, and justices would use this power to impose their policy or political preferences under the guise of interpretation. Although Alexander Hamilton’s famous Federalist 78 attempted to allay those fears about judicial power, it is fair to say that Brutus’ prediction about judicial supremacy came true. Within fifty years Daniel Webster was equating disagreeing with a constitutional decision of the Supreme Court with an invitation to anarchy. Later, Abraham Lincoln contended that accepting the Court as ultimate interpreter of the Constitution, as Stephen Douglas said Americans must do, meant that opponents of slavery would have to submit to the reasoning of the Court’s Dred Scott decision, which held that free blacks could never be citizens. Whether the Supreme Court should exercise the power of judicial review to strike down legislation because the justices think it is bad policy has also been a consistent source of controversy throughout its history. Brutus envisioned justices doing this, as did the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson and Lochner v. New York.

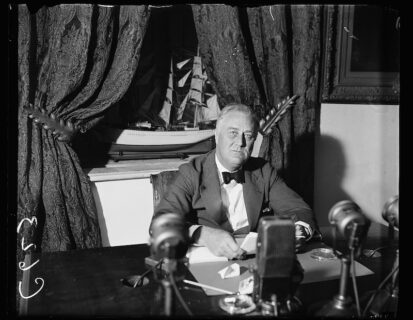

As the Court’s power developed and expanded, other institutions tried to impose limits, most significantly in Franklin Roosevelt’s court-packing plan. While Congress decisively rejected that proposal, more recently the idea of expanding the Court to change its ideological composition—that is, to change it to reach desired political outcomes—has been resuscitated in response to Republican senators delaying the replacement of Antonin Scalia and accelerating the replacement of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But these conflicts really point to a more fundamental conflict over how the Constitution should be interpreted. In response to decisions that struck them as untethered from the text, conservatives have argued that the only way to reconcile judicial power with republican self-government is for judges to interpret the Constitution according to its original meaning (See Speech to the American Bar Association and Originalism: The Lesser Evil). Originalism, initially derided by legal and political elites, has now become so entrenched that even some progressive constitutional scholars have declared, “We’re all originalists now.” Ironically, it now appears that some on the right have lost their faith in originalism and are offering interpretive arguments that seem more resonant with the living constitutionalism of liberal stalwarts like William Brennan.

The debate over judicial power has also led to other debates over judicial representation. For much of the Supreme Court’s history presidents tried to preserve geographic diversity by ensuring that the Court always included justices from different regions of the country. Today that concern has shifted to what some have called “identity politics”—how judges’ race and sex might affect their decisions. Should those aspects of personal identity matter when judges decide cases? Will judges from particular ethnic backgrounds make better judges, as Justice Sotomayor once contended? If so, then what are the implications of that for principles of constitutional equality and the rule of law?

Constitutional Interpretation

- Brutus XV, March 20, 1788

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 78, May 28, 1788

- Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

- Chief Justice John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, March 6, 1819

- Justice Henry Billings Brown, Justice John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v. Ferguson, May 18, 1896

- Justice Rufus W. Peckham, Justice John Marshall Harlan, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Lochner v. New York, April 17, 1905

- Attorney General Ed Meese, Speech to the American Bar Association, July 9, 1985

- Justice William Brennan, “The Constitution of the United States: Contemporary Ratification,” October 12, 1985

- Judge Richard Posner, “What Am I? A Potted Plant? The Case against Strict Construction,” September 28, 1987

- Justice Antonin Scalia, “Originalism: The Lesser Evil,” September 16, 1988

- Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “Speaking in a Judicial Voice,” March 9, 1992

- Justice Stephen Breyer, “Our Democratic Constitution,” October 22, 2001

- Justice Anthony Kennedy, Chief Justice John Roberts, Obergefell v. Hodges, June 26, 2015

- Adrian Vermeule, “Beyond Originalism,” March 31, 2020

Departmentalism

- Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to William Torrance, June 11, 1815

- President Andrew Jackson, Veto of the Bank Bill, July 10, 1832

- Senator Daniel Webster, Reply to Jackson’s Veto Message, July 11, 1832

- Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857

- Senator Stephen Douglas, Speech at Springfield, Illinois, July 17, 1858

Judicial Independence

- Brutus XV, March 20, 1788

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 78, May 28, 1788

- Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on the Reorganization of the Judiciary, March 9, 1937

- Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Reorganization of the Federal Judiciary, June 7, 1937

Judicial Review

- Brutus XV, March 20, 1788

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 78, May 28, 1788

- Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to William Torrance, June 11, 1815

- President Andrew Jackson, Veto of the Bank Bill, July 10, 1832

- Senator Daniel Webster, Reply to Jackson’s Veto Message, July 11, 1832

- Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857

- Senator Stephen Douglas, Speech at Springfield Illinois, July 17, 1858

- Per curiam opinion, Cooper v. Aaron, September 29, 1958

Judicial Role

- Brutus XV, March 20, 1788

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 78, May 28, 1788

- Justice Robert Jackson, Justice Felix Frankfurter, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, June 14, 1943

- Per curiam opinion, Cooper v. Aaron, September 29, 1958

- Chief Justice Earl Warren, Justice John Marshall Harlan II, Reynolds v. Sims, June 15, 1964

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, “The Sword and the Robe,” May 8, 1981

- Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “Speaking in a Judicial Voice,” March 9, 1992

- Justice Clarence Thomas, Missouri v. Jenkins, June 12, 1995

Lochner Era

- Justice Rufus W. Peckham, Justice John Marshall Harlan, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Lochner v. New York, April 17, 1905

- Justice Stephen Breyer, “Our Democratic Constitution,” October 22, 2001

- Justice Anthony Kennedy, Chief Justice John Roberts, Obergefell v. Hodges, June 26, 2015

Necessary and Proper

- Chief Justice John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, March 6, 1819

- President Andrew Jackson, Veto of the Bank Bill, July 10, 1832

- Senator Daniel Webster, Reply to Jackson’s Veto Message, July 11, 1832

Originalism and Living Constitutionalism

- Attorney General Ed Meese, Speech to the American Bar Association, July 9, 1985

- Justice William Brennan, “The Constitution of the United States: Contemporary Ratification,” October 12, 1985

- Judge Richard Posner, “What Am I? A Potted Plant? The Case against Strict Construction,” September 28, 1987

- Justice Antonin Scalia, “Originalism: The Lesser Evil,” September 16, 1988

- Justice Anthony Kennedy, Chief Justice John Roberts, Obergefell v. Hodges, June 26, 2015

- Adrian Vermeule, “Beyond Originalism,” March 31, 2020

Race and the Supreme Court

- Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857

- Senator Stephen Douglas, Speech at Springfield, Illinois, July 17, 1858

- Justice Henry Billings Brown and Justice John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v. Ferguson, May 18, 1896

- Per curiam opinion, Cooper v. Aaron, September 29, 1958

- Justice Clarence Thomas, Missouri v. Jenkins, June 12, 1995

- Judge Sonia Sotomayor, “A Latina Judge’s Voice,” October 26, 2001

A. Why did Brutus claim that errors of judgment were not included in “high crimes and misdemeanors”? If he was correct, how did this strengthen judicial power? Why did Brutus think that the power of the Supreme Court would exceed the legislative power?

B. Compare Brutus’ concerns about constitutional interpretation to Justice Brennan’s defense of living constitutionalism. How would Brutus evaluate Brennan’s treatment of the Constitution?

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 78, May 28, 1788

A. Compare Hamilton’s case for the judiciary being the “least dangerous branch” to Brutus’ argument that it could be the most dangerous branch. Do you find Hamilton’s argument that the Court only has the power of “judgment” but not “force” or “will” persuasive? Why did Hamilton think that it was not only safe but also necessary to give judges life tenure in a republican government?

B. Compare Hamilton’s case for the Court being the “least dangerous branch” to Lincoln’s critique of judicial power. Would Hamilton agree or disagree with Lincoln’s argument that Supreme Court decisions were only fully binding when they were “fully settled”?

Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

A. What might have been the political consequences if Marshall had asserted judicial supremacy in Marbury v. Madison? After Marbury the Supreme Court did not exercise judicial review over a federal law again until Dred Scott v. Sandford. Why do you think it was so rarely used during that period?

B. Is Marshall’s reasoning similar to Hamilton’s or different? Did Marshall envision a more modest role for the Court than Hamilton?

Thomas Jefferson to William Torrance, June 11, 1815

A. Jefferson argued that when institutions disagreed over constitutional questions, the prudence of public officials or the weight of public opinion would lead to compromise and avoid constitutional crises. Do you find his position too optimistic? Can you think of important political issues that do not raise constitutional questions that support his position? Even if his position was optimistic, was it nevertheless constitutionally justified? If members of Congress and the president accepted and argued for Jefferson’s position today, how would it change our politics and public deliberation over constitutional questions? Would the American people know more about the Constitution if they understood that political officers also have the authority to interpret the Constitution?

B. Compare Jefferson’s position on the role of the Court to Ginsburg’s, Thomas’, and Breyer’s. Are they similar? Would Jefferson have been persuaded by Scalia’s argument that originalism can reconcile judicial power with representative government?

Chief Justice John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, March 6, 1819

A. Would it have been possible, as critics of the decision such as James Madison argued, for the Court to have upheld the constitutionality of the bank without such a broad reading of the necessary and proper clause?

B. How would Brutus have evaluated Marshall’s reasoning in McCulloch v. Maryland? Is Marshall’s reasoning consistent with Hamilton’s defense of the Supreme Court and how he envisioned justices interpreting the law?

President Andrew Jackson, Veto of the Bank Bill, July 10, 1832

A. Why did Jackson believe that precedent is a dangerous source of authority? Even if you accept judicial supremacy, does his position have implications for how Supreme Court justices should treat precedents? How much weight should justices give precedents that they believe wrongly interpreted the Constitution? What are the implications for separation of powers if Congress and the president must follow what they believe is unconstitutional reasoning of the Supreme Court?

B. Compare Jackson’s interpretation of the necessary and proper clause to Marshall’s. Whose interpretation is more faithful to the Constitution?

Senator Daniel Webster, Reply to Jackson’s Veto Message, July 11, 1832

A. Should presidents, as Webster argued, be bound by the constitutional interpretations of past Congresses, presidents, and courts? If a president sincerely believes that a previous interpretation was constitutionally incorrect and followed it because of Webster’s reasoning, would he violate his oath of office?

B. Webster contended that Jackson was claiming a universal power. How would you describe the power that he was ascribing to the Supreme Court?

Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857

A. Are there any Supreme Court decisions that would count as fully settled under Lincoln’s definition? What actions did Lincoln take as president that violated the reasoning of Dred Scott and illustrated his position about the limits of the Court’s power?

B. Compare Lincoln’s argument about judicial power to the Court’s reasoning in Cooper v. Aaron? How would Jefferson or Lincoln have responded to the Court’s claim of judicial supremacy in Cooper? Do Lincoln’s arguments against Chief Justice Taney’s reasoning in Dred Scott confirm Brutus’ fears about the Supreme Court?

Senator Stephen Douglas, Speech at Springfield, Illinois, July 17, 1858

A. Douglas argued that judicial supremacy is essential for preserving individual rights. Is this true? How would Dred Scott have responded to this claim?

B. Does Douglas’ point about the difficulty of changing the Court’s direction through nominations actually illustrate Lincoln’s argument about the dangers of judicial supremacy?

Justice Henry Billings Brown, Justice John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v. Ferguson, May 18, 1896

A. Should justices make decisions based on whether they think particular laws are reasonable, as Justice Brown asserted? If not, as Justice Harlan contended, what can be done about extraordinarily bad laws that do not violate the Constitution? Justice Harlan argued for a color-blind Constitution. What would that mean for how the Supreme Court interprets the Fourteenth Amendment?

B. Would Brutus or Hamilton have agreed with Harlan’s position on judges making decisions based on policy grounds?

A. The majority argued that states can legitimately regulate unhealthy occupations. What constitutes an unhealthy occupation? Based on Justice Holmes’ dissent could there be any limits on states’ authority to regulate economic activity under their police powers? Should the fact that the Bakeshop Act largely affected small bakeries owned by Italian, French, and Jewish immigrants rather than large, established bakeries affect our evaluation of its legitimacy?

B. How does Justice Holmes’ dissent differ from both the majority opinion and Justice Harlan’s dissent? Compare Justice Harlan’s dissent in Lochner to his dissent in Plessy. Why did he believe the exercise of the police power was legitimate in the former but not the latter?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on the Reorganization of the Judiciary, March 9, 1937

A. Roosevelt said that the three-horse team of the president, Congress, and the Supreme Court must pull in unison. Is that the Founders’ understanding of separation of powers and checks and balances? Roosevelt denied that he was trying to “drive that team.” Was that claim plausible? How did Roosevelt reconcile saying that he wanted both a Court “that will refuse to amend the Constitution by the arbitrary exercise of judicial power” and also justices with a more “modern” perspective?

B. Is Roosevelt’s view of the Supreme Court and the respect it deserves similar to or different from Jackson’s or Lincoln’s?

Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Reorganization of the Federal Judiciary, June 7, 1937

A. The report called Roosevelt’s plan an unprecedented attack on judicial independence. Was this true? Is judicial independence as important as the report claimed? If the Supreme Court is significantly out of step with contemporary attitudes on how the Constitution should be interpreted, are there any plausible reforms that would satisfy the standards of this report?

B. Compare the report’s argument for judicial independence to Webster’s and Douglas’. Do they share a similar view of judicial independence?

A. Were Frankfurter and other legal progressives correct that increased judicial resolution of political disputes creates a threat to liberty? Justice Frankfurter argued that some questions are beyond the Court’s competence to answer effectively. How did Justice Jackson respond? Is his response persuasive?

B. Compare Frankfurter’s position to Harlan’s and Holmes’ dissents in Lochner. Which one is closest to Frankfurter’s view of judicial deference?

Per curiam opinion, Cooper v. Aaron, September 29, 1958

A. Can the Court’s claim that its interpretations are the supreme law of the land be reconciled with the idea that the Constitution is America’s fundamental law?

B. If the Court’s decisions are not the supreme law of the land, would that invite constitutional crises? How would Jefferson respond to that concern? Compare Justice Ginsburg’s evaluation of Brown v. Board of Education to the Court’s claims in Cooper. Is her reading of Brown and the power of the Court narrower than the Court’s in Cooper?

Chief Justice Earl Warren, Justice John Marshall Harlan II, Reynolds v. Sims, June 15, 1964

A. If partisan gerrymandering, which the Court has said does not violate the Constitution, can lead to the same results as malapportionment through “cracking” and “packing,”1 should states be able to apportion along jurisdictional lines similar to how the Senate is apportioned along state lines at the federal level? Is there a danger of concentrating power in the Supreme Court even when done for salutary purposes?

B. Compare Justice Harlan’s argument for judicial restraint to Justice Holmes’ dissent in Lochner. Is one more concerned with liberty than the other?

Justice Thurgood Marshall, “The Sword and the Robe,” May 8, 1981

A. In 1987, Justice Marshall delivered a speech called “The Constitution: A Living Document.” Living constitutionalism is the view that justices should interpret the Constitution in light of changing social circumstances. Can Marshall’s position that the Court is by necessity insulated from “changing public concerns” be reconciled with living constitutionalism? Why is it important that justices do not publicly comment on their “favored solutions for society’s problems”?

B. Compare Marshall’s position to Meese’s. In what ways do their views of the justices’ roles differ? In what ways are they similar?

Attorney General Ed Meese, Speech to the American Bar Association, July 9, 1985

A. How did Meese argue that anything other than originalism is “totally at odds with the logic of our Constitution”? Why did he think that judicial decisions can undermine the rule of law? Meese argued that the Court has undermined the ability of states to act as a barrier against centralization of power. How did he say the Court has done this?

B. Does Meese’s description of how the Court has centralized power sound similar to how Brutus predicted the Court would do this? If not, how has it proceeded differently than Brutus predicted?

A. Justice Brennan said that “when justices interpret the Constitution they speak for their community, not for themselves alone. The act of interpretation must be undertaken with full consciousness that it is, in a very real sense, the community’s interpretation that is sought.” How did he reconcile this with his argument that “it is the very purpose of a Constitution—and particularly of the Bill of Rights—to declare certain values transcendent, beyond the reach of temporary political majorities”? What should a justice do, for instance, if the community’s interpretation rejects his understanding of transcendent values?

B. How would Brutus or Jefferson respond to Brennan’s claim that the most important question is, “What do the words of the text mean in our time?” If this is the most important question, is the Supreme Court the best institution to answer it?

A. Judge Posner said that judges inevitably make law, but he also indicated that there are better and worse forms of judicial legislation. What standards did he seem to have for judicial legislation?

B. How would an originalist such as Edwin Meese respond to Posner’s claim that the “Constitution does not say, “‘Read me broadly’ or ‘Read me narrowly’”? Is there any necessary contradiction between saying that the general provisions of the Constitution must be read broadly and originalism?

Justice Antonin Scalia, “Originalism: The Lesser Evil,” September 16, 1988

A. Scalia argued that originalism is preferable to nonoriginalism, but he acknowledged some weaknesses of originalism. What are they? Why did he believe those weaknesses to be preferable to the weaknesses of nonoriginalism? Why did Scalia argue that stare decisis is more incompatible with nonoriginalism than originalism? What role should stare decisis play under a written constitution?

B. Why did Scalia believe originalism to be necessary for reconciling judicial power with constitutional government? Would Brutus or Hamilton agree with him?

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “Portia’s Progress,” October 29, 1991

A. If women and men should decide cases the same way, as Justice O’Connor suggested, why should it matter if there are female justices on the Court? Is Justice O’Connor correct in saying that the idea that women might decide cases differently represents a threat to the political, social, and legal gains made by women in the twentieth century?

B. Is Justice O’Connor’s view of the judicial role similar to or different from Justice Thurgood Marshall’s?

Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “Speaking in a Judicial Voice,” March 9, 1993

A. Was Justice Ginsburg correct in saying that a more measured opinion in Roe would have limited the controversy surrounding the decision? Is the equal protection clause a more plausible constitutional foundation for Roe than the right to privacy?

B. Justice Ginsburg contended that a dialogue between the judiciary and the states can be fruitful. Is this similar to Ed Meese’s argument that the states should be able to resist the Court’s decisions?

Justice Clarence Thomas, Missouri v. Jenkins, June 12, 1995

A. Was Justice Thomas correct in his analysis of the racial assumptions behind the trial court’s remedial plan? How far should federal courts be able to go in remedying constitutional harms? Was Thomas correct that the trial court had gone too far in Missouri v. Jenkins?

B. What does Justice Thomas’ discussion of Brutus and Hamilton tell us about the debate over the judiciary at the founding? Whose predictions about the judiciary were more accurate?

Justice Stephen Breyer, “Our Democratic Constitution,” October 21, 2001

A. In Justice Breyer’s view, even if judges cannot avoid subjectivity, it is nevertheless important for them to constrain it. Why? What is the “privacy problem” according to Justice Breyer? Why would his approach of “active liberty” lead to better results than other interpretative approaches such as originalism?

B. Compare Justice Breyer’s active liberty to Justice Brennan’s approach to constitutional interpretation. Would Brennan agree with Breyer’s approach?

Judge Sonia Sotomayor, “A Latina Judge’s Voice,” October 26, 2001

A. Was Justice Sotomayor correct in saying that those from particular racial and ethnic backgrounds have an advantage in reaching wise decisions as judges? If that is not the case, should we nevertheless seek to increase diversity on the bench? Should we regard the goal of judicial objectivity as just an aspiration? If we agree that objectivity is just an aspiration, would that have any effect on how judges decide cases? If the race, sex, and personal experiences of judges inevitably affect their legal reasoning, what are the implications for achieving equal justice under law?

B. Compare Justice Marshall’s case for judicial neutrality to Justice Sotomayor’s claim that a judge’s background must affect their decision making. Can these two positions be reconciled? How does Justice Sotomayor’s description of the traits necessary to be an effective judge compare to Hamilton’s?

Justice Anthony Kennedy, Chief Justice John Roberts, Obergefell v. Hodges, June 26, 2015

A. Justice Kennedy grounded the majority’s decision in a right to equal dignity. What does that mean? Did he propose any limits to that right? If, as Justice Kennedy said, the meaning of liberty changes over time, how do we know when its meaning has changed?

B. How would Brutus evaluate the Court’s reasoning in Obergefell? Chief Justice Roberts argued that the majority’s decision was based on their preferences, not the Constitution. What were his arguments for that position? Compare his reasoning to Justice Harlan’s dissent in Plessy and Justice Holmes’ dissent in Lochner.

Adrian Vermeule, “Beyond Originalism,” March 31, 2020

A. Why did Vermeule think that originalism has outlived its usefulness? What are the principles he identified as part of his common-good constitutionalism?

B. How did Vermeule draw on Brennan’s language to buttress his argument for common-good constitutionalism? Compare Professor Vermeule’s approach to constitutional interpretation to Justice Brennan’s and Judge Posner’s. If Brennan’s and Posner’s positions are correct, can there be any principled disagreement with Professor Vermeule?

Agresto, John. The Supreme Court and Constitutional Democracy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984.

Balkin, Jack M. Living Originalism. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2011.

Barnett, Randy E. Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the People. New York: Broadside Books, 2016.

Bernstein, David E. Rehabilitating Lochner: Defending Individual Rights against Progressive Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Bickel, Alexander, The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Chemerinsky, Erwin. “In Defense of Judicial Supremacy.” William & Mary Law Review 58 (2017): 1459–1494.

Dworkin, Ronald. Freedom’s Law: The Moral Reading of the American Constitution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Ely, John Hart. Democracy and Distrust: A Theory of Judicial Review. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Engdahl, David E. “John Marshall’s ‘Jeffersonian’ Concept of Judicial Review.” Duke Law Journal 42 (1992): 279–339.

Fisher, Louis. Reconsidering Judicial Finality: Why the Supreme Court Is Not the Last Word on the Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2019.

Gillman, Howard. The Constitution Besieged: The Rise & Demise of Lochner Era Police Powers Jurisprudence. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

Kahn, Ronald, and Ken Kersch, eds. The Supreme Court and American Political Development. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2006.

Kramer, Larry D. The People Themselves: Popular Constitutionalism and Judicial Review. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

McDowell, Gary L. Equity and the Constitution: The Supreme Court, Equitable Relief, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Paulsen, Michael Stokes, “Marbury‘s Wrongness.” Constitutional Commentary 20 (2003): 343–357.

Segall, Eric J. Originalism as Faith. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Tribe, Laurence H. “On Judicial Review.” Dissent 52 (summer 2005): 81–83.

Tushnet, Mark. Taking the Constitution away from the Court. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Vermeule, Adrian, Common Good Constitutionalism. Cambridge UK: Polity, 2022.

Waldron, Jeremy. “Judicial Review and the Conditions of Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 6 (1998): 335–355.

Weiner, Greg. The Political Constitution: The Case against Judicial Supremacy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2019.

Whittington, Keith E. Constitutional Interpretation: Textual Meaning, Original Intent, and Judicial Review. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1999.

_______. Political Foundations of Judicial Supremacy: The Presidency, the Supreme Court, and Constitutional Leadership in U.S. History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Wolfe, Christopher. The Rise of Modern Judicial Review: From Judicial Interpretation to Judge Made Law. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1994.

Wurman, Ilan. A Debt against the Living: An Introduction to Originalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.