No related resources

Introduction

In 1895, New York passed the Bakeshop Act, which limited the number of hours bakers could work to no more than ten hours a day or sixty hours per week. Bakery owner Joseph Lochner asked his employees to work more than sixty hours and was subsequently fined fifty dollars. Lochner challenged his punishment, claiming that the act violated his “liberty of contract” protected under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (“nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”). In a 5–4 decision, the Court ruled in Lochner’s favor. The Court found that New York had exceeded its police powers—the general power of government to protect the health, welfare, safety, and morals of the people—since it had not provided evidence that the law protected the health of workers or the public. The case lent its name to an entire era of jurisprudence, the Lochner era, which lasted from Allgeyer v. Louisana (1897), cited as a precedent in Lochner, to West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). During this period the Court often struck down economic regulations as violations of the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendments’ due process clauses. The Court said that those clauses contained a “liberty of contract” which forbade arbitrary governmental interference in the right of individuals to make contracts with others.

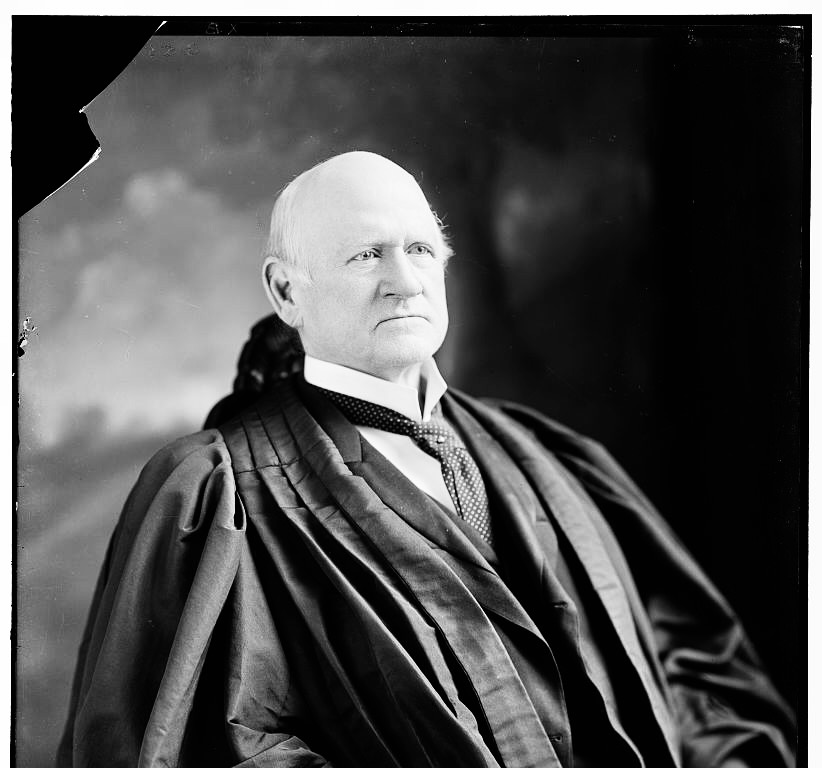

The majority opinion of Justice Rufus W. Peckham (1838–1909) held that the regulation of this particular occupation was inherently arbitrary and if sanctioned would allow states to regulate every “act of the individual.” In dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan (1833–1911) argued that the case should have been decided in favor of New York. In the post-Lochner era, Harlan’s opinion was used to help craft the “rational basis test,” particularly as it was articulated in U.S. v. Carolene Products (1938). Rational basis review gives deference to the judgment of legislatures on most constitutional questions, including whether the government had violated due process or equal protection of the law. Harlan’s position, however, still required the government to produce facts and evidence to demonstrate that its policies were rationally related to the legitimate government interest it was trying to achieve. (The Supreme Court has created more exacting levels of scrutiny for some constitutional questions. When a government policy infringes on a fundamental right or involves a suspect classification such as race, it must satisfy strict scrutiny. When the government makes classification based on sex or illegitimacy, it must satisfy intermediate scrutiny.)

The most famous dissent in the case, perhaps the most famous dissent in Supreme Court history after Harlan’s dissent in Plessy, came from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935) and offered an even more lenient standard for evaluating government action. His biting opinion accused the majority of writing their own economic preferences into law, summarized in his line “the Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics.” Spencer (1820–1903) was an English social theorist famous for coining the phrase “survival of the fittest.” Thus, Holmes implied that the majority was reading social Darwinism into the Constitution. Holmes was himself inclined to social Darwinism, although none of his colleagues on the Court reasonably fit that label. Holmes, however, believed that it was not his place as a justice to impose his social Darwinist preferences on the country and largely deferred to legislatures. His social Darwinism can be seen in his majority decision for the Court in Buck v. Bell (1927), which authorized the forced sterilization of people alleged to be unfit. “Three generations of imbeciles are enough,” he concluded. Ultimately, Holmes followed the admonition of James Bradley Thayer, his teacher at Harvard Law School, that justices should not strike down legislation unless its unconstitutionality is “so clear that it is not open to rational question.” Holmes’ version of “Thayerian deference” to legislatures and rational basis review would become the position of leading progressive scholars opposed to judicial invalidation of economic regulations. Holmes’ version of rational-basis review also supplanted Harlan’s version with the Court’s unanimous decision in Williamson v. Lee Optical (1955), a decision written by Justice William O. Douglas (1898–1980).

The Lochner decision and era also provide a useful window into debates over judicial power from the past fifty years. Conservatives have considered Lochner entirely irredeemable. Robert Bork called it “the symbol, indeed the quintessence, of judicial usurpation of power.” In this view, in Lochner the Court both misinterpreted the Constitution and the Court’s proper constitutional role. Reading a liberty of contract into the due process allowed the Court to arbitrarily strike down legislation. This kind of judicial activism, conservatives contend, is fundamentally at odds with constitutional principles of representative government and separation of powers.

With the rise of the Warren Court (1953–1969), liberal and progressive scholars largely abandoned Thayerian deference and judicial restraint, which in turn required them to modify their evaluation of Lochner. The Court, they argued, misinterpreted the Constitution but not the Court’s proper role. The Court’s error was not in intervening to protect liberty but in its understanding of what liberty actually requires. It is necessary for the Court to exercise judicial review on the broad substantive grounds outlined by the Warren Court and in later decisions such as Roe v. Wade (1973) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

More recently, libertarian scholars have argued that the Court was right to protect economic liberty and that the doctrine of liberty of contract served as an important protection of civil rights and liberties for racial and ethnic minorities. The Bakeshop Act, they point out, was largely supported by workers at established large bakeries as a way of undercutting competition from small bakeries owned by recently arrived Italian, French, or Jewish immigrants, who did not have the resources or economies of scale to comply with the law. Thus, in striking down the law, according to the libertarians, the Court was protecting the interests of those with fewer resources. Libertarians point to other cases during the Lochner era, such as Buchanan v. Warley (1917), as examples of how liberty of contract protected minorities. In Warley, the Supreme Court struck down as a violation of liberty of contract a segregationist zoning statute from Louisville, Kentucky, which forbade whites from selling property to blacks on majority white blocks, and vice versa

Source: 198 U.S. 45; https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/198/45.

Justice PECKHAM delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by Chief Justice FULLER and Justices BREWER, BROWN, and McKENNA.

…The indictment … charges that [Mr. Lochner] violated the … labor law of the state of New York, in that he wrongfully and unlawfully required and permitted an employee working for him to work more than sixty hours in one week. . . .The mandate of the statute that “no employee shall be required or permitted to work” is the substantial equivalent of an enactment that “no employee shall contract or agree to work” more than ten hours per day, and, as there is no provision for special emergencies, the statute is mandatory in all cases. It is not an act merely fixing the number of hours which shall constitute a legal day’s work, but an absolute prohibition upon the employer permitting, under any circumstances, more than ten hours’ work to be done in his establishment. The employee may desire to earn the extra money which would arise from his working more than the prescribed time, but this statute forbids the employer from permitting the employee to earn it.

The statute necessarily interferes with the right of contract between the employer and employees concerning the number of hours in which the latter may labor in the bakery of the employer. The general right to make a contract in relation to his business is part of the liberty of the individual protected by the Fourteenth Amendment of the federal Constitution. . . .The right to purchase or to sell labor is part of the liberty protected, unless there are circumstances which exclude the right. There are, however, certain powers, existing in the sovereignty of each state in the Union, somewhat vaguely termed police powers, the exact description and limitation of which have not been attempted by the courts. Those powers, broadly stated, and without, at present, any attempt at a more specific limitation, relate to the safety, health, morals, and general welfare of the public. Both property and liberty are held on such reasonable conditions as may be imposed by the governing power of the state in the exercise of those powers, and with such conditions the Fourteenth Amendment was not designed to interfere.

The state therefore has power to prevent the individual from making certain kinds of contracts. . . .Therefore, when the state, by its legislature, in the assumed exercise of its police powers, has passed an act which seriously limits the right to labor or the right of contract in regard to their means of livelihood between persons who are sui juris1 (both employer and employee), it becomes of great importance to determine which shall prevail—the right of the individual to labor for such time as he may choose, or the right of the state to prevent the individual from laboring or from entering into any contract to labor beyond a certain time prescribed by the state.

This court has recognized the existence and upheld the exercise of the police powers of the states. . . .Among the later cases where the state law has been upheld by this court is that of . . . the act of the legislature of Utah . . . limiting the employment of workmen in all underground mines or workings to eight hours per day “except in cases of emergency, where life or property is in imminent danger.” It also limited the hours of labor in smelting and other institutions for the reduction or refining of ores or metals to eight hours per day except in like cases of emergency. The act was held to be a valid exercise of the police powers of the state [because]. . . the kind of employment, mining, smelting, etc., and the character of the employees in such kinds of labor, were such as to make it reasonable and proper for the state to interfere to prevent the employees from being constrained by the rules laid down by the proprietors in regard to labor. . . .

It must, of course, be conceded that there is a limit to the valid exercise of the police power by the state. There is no dispute concerning this general proposition. Otherwise the Fourteenth Amendment would have no efficacy and the legislatures of the states would have unbounded power, and it would be enough to say that any piece of legislation was enacted to conserve the morals, the health, or the safety of the people; such legislation would be valid, no matter how absolutely without foundation the claim might be. The claim of the police power would be a mere pretext—become another and delusive name for the supreme sovereignty of the state to be exercised free from constitutional restraint. This is not contended for. In every case that comes before this court, therefore, where legislation of this character is concerned, and where the protection of the federal Constitution is sought, the question necessarily arises: Is this a fair, reasonable, and appropriate exercise of the police power of the state, or is it an unreasonable, unnecessary, and arbitrary interference with the right of the individual to his personal liberty, or to enter into those contracts in relation to labor which may seem to him appropriate or necessary for the support of himself and his family? Of course the liberty of contract relating to labor includes both parties to it. The one has as much right to purchase as the other to sell labor.

This is not a question of substituting the judgment of the court for that of the legislature. If the act be within the power of the state it is valid, although the judgment of the court might be totally opposed to the enactment of such a law. But the question would still remain: Is it within the police power of the state? and that question must be answered by the court.

The question whether this act [of New York] is valid as a labor law, pure and simple, may be dismissed in a few words. There is no reasonable ground for interfering with the liberty of person or the right of free contract by determining the hours of labor in the occupation of a baker. There is no contention that bakers as a class are not equal in intelligence and capacity to men in other trades or manual occupations, or that they are not able to assert their rights and care for themselves without the protecting arm of the state interfering with their independence of judgment and of action. They are in no sense wards of the state. Viewed in the light of a purely labor law, with no reference whatever to the question of health, we think that a law like the one before us involves neither the safety, the morals, nor the welfare of the public, and that the interest of the public is not in the slightest degree affected by such an act. The law must be upheld, if at all, as a law pertaining to the health of the individual engaged in the occupation of a baker. It does not affect any other portion of the public than those who are engaged in that occupation. Clean and wholesome bread does not depend upon whether the baker works but ten hours per day or only sixty hours a week. The limitation of the hours of labor does not come within the police power on that ground. . . .

We think the limit of the police power has been reached and passed in this case. There is, in our judgment, no reasonable foundation for holding this to be necessary or appropriate as a health law to safeguard the public health or the health of the individuals who are following the trade of a baker. If this statute be valid, and if, therefore, a proper case is made out in which to deny the right of an individual, sui juris, as employer or employee, to make contracts for the labor of the latter under the protection of the provisions of the federal Constitution, there would seem to be no length to which legislation of this nature might not go. . . .

We think that there can be no fair doubt that the trade of a baker, in and of itself, is not an unhealthy one to that degree which would authorize the legislature to interfere with the right to labor, and with the right of free contract on the part of the individual, either as employer or employee. In looking through statistics regarding all trades and occupations, it may be true that the trade of a baker does not appear to be as healthy as some other trades, and is also vastly more healthy than still others. To the common understanding, the trade of a baker has never been regarded as an unhealthy one. Very likely, physicians would not recommend the exercise of that or of any other trade as a remedy for ill health. Some occupations are more healthy than others, but we think there are none which might not come under the power of the legislature to supervise and control the hours of working therein if the mere fact that the occupation is not absolutely and perfectly healthy is to confer that right upon the legislative department of the government. It might be safely affirmed that almost all occupations more or less affect the health. There must be more than the mere fact of the possible existence of some small amount of unhealthiness to warrant legislative interference with liberty. It is unfortunately true that labor, even in any department, may possibly carry with it the seeds of unhealthiness. But are we all, on that account, at the mercy of legislative majorities? A printer, a tinsmith, a locksmith, a carpenter, a cabinetmaker, a dry goods clerk, a bank’s, a lawyer’s, or a physician’s clerk, or a clerk in almost any kind of business, would all come under the power of the legislature, on this assumption. No trade, no occupation, no mode of earning one’s living, could escape this all-pervading power, and the acts of the legislature in limiting the hours of labor in all employments would be valid although such limitation might seriously cripple the ability of the laborer to support himself and his family. . . .

. . . Statutes of the nature of that under review, limiting the hours in which grown and intelligent men may labor to earn their living, are mere meddlesome interferences with the rights of the individual. . . .

. . .The state in that case would assume the position of a supervisor, or pater familias,2 over every act of the individual, and its right of governmental interference with his hours of labor, his hours of exercise, the character thereof, and the extent to which it shall be carried would be recognized and upheld. In our judgment, it is not possible, in fact, to discover the connection between the number of hours a baker may work in the bakery and the healthful quality of the bread made by the workman. The connection, if any exist, is too shadowy and thin to build any argument for the interference of the legislature. If the man works ten hours a day it is all right, but if ten and a half or eleven, his health is in danger and his bread may be unhealthful, and, therefore, he shall not be permitted to do it. This, we think, is unreasonable and entirely arbitrary. . . .

It is manifest to us that the limitation of the hours of labor. . . has no such direct relation to, and no such substantial effect upon, the health of the employee as to justify us in regarding the section as really a health law. It seems to us that the real object and purpose were simply to regulate the hours of labor between the master and his employees (all being men sui juris) in a private business, not dangerous in any degree to morals or in any real and substantial degree to the health of the employees. Under such circumstances, the freedom of master and employee to contract with each other in relation to their employment, and in defining the same, cannot be prohibited or interfered with without violating the federal Constitution. . . .

Justice HARLAN dissenting, joined by Justices WHITE and DAY:

. . . Speaking generally, the state, in the exercise of its powers, may not unduly interfere with the right of the citizen to enter into contracts that may be necessary and essential in the enjoyment of the inherent rights belonging to everyone, among which rights is the right “to be free in the enjoyment of all his faculties; to be free to use them in all lawful ways; to live and work where he will; to earn his livelihood by any lawful calling; to pursue any livelihood or avocation.”3…

[But] I take it to be firmly established that what is called the liberty of contract may, within certain limits, be subjected to regulations designed and calculated to promote the general welfare or to guard the public health, the public morals, or the public safety. . . .

. . .[A]ssuming, as according to settled law we may assume, that such liberty of contract is subject to such regulations as the state may reasonably prescribe for the common good and the well-being of society, what are the conditions under which the judiciary may declare such regulations to be in excess of legislative authority and void? Upon this point there is no room for dispute; for the rule is universal that a legislative enactment, federal or state, is never to be disregarded or held invalid unless it be, beyond question, plainly and palpably in excess of legislative power. . .If there be doubt as to the validity of the statute, that doubt must therefore be resolved in favor of its validity, and the courts must keep their hands off, leaving the legislature to meet the responsibility for unwise legislation. . . .

Let these principles be applied to the present case. . . .

It is plain that this statute was enacted in order to protect the physical well-being of those who work in bakery and confectionery establishments. It may be that the statute had its origin, in part, in the belief that employers and employees in such establishments were not upon an equal footing, and that the necessities of the latter often compelled them to submit to such exactions as unduly taxed their strength. Be this as it may, the statute must be taken as expressing the belief of the people of New York that, as a general rule, and in the case of the average man, labor in excess of sixty hours during a week in such establishments may endanger the health of those who thus labor. Whether or not this be wise legislation it is not the province of the court to inquire. Under our systems of government, the courts are not concerned with the wisdom or policy of legislation. . . .I find it impossible, in view of common experience, to say that there is here no real or substantial relation between the means employed by the state and the end sought to be accomplished by its legislation. . . . Still less can I say that the statute is, beyond question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law. . . .Therefore I submit that this court will transcend its functions if it assumes to annul the statute of New York. It must be remembered that this statute does not apply to all kinds of business. It applies only to work in bakery and confectionery establishments, in which, as all know, the air constantly breathed by workmen is not as pure and healthful as that to be found in some other establishments or out of doors. . . .

[A] writer says:. . .“Nearly all bakers are pale-faced and of more delicate health than the workers of other crafts, which is chiefly due to their hard work and their irregular and unnatural mode of living, whereby the power of resistance against disease is greatly diminished. The average age of a baker is below that of other workmen; they seldom live over their fiftieth year, most of them dying between the ages of forty and fifty. During periods of epidemic diseases, the bakers are generally the first to succumb to the disease, and the number swept away during such periods far exceeds the number of other crafts in comparison to the men employed in the respective industries. . . .”

We judicially know that the question of the number of hours during which a workman should continuously labor has been, for a long period, and is yet, a subject of serious consideration among civilized peoples and by those having special knowledge of the laws of health. Suppose the statute prohibited labor in bakery and confectionery establishments in excess of eighteen hours each day. No one, I take it, could dispute the power of the state to enact such a statute. But the statute before us does not embrace extreme or exceptional cases. It may be said to occupy a middle ground in respect of the hours of labor. What is the true ground for the state to take between legitimate protection, by legislation, of the public health and liberty of contract is not a question easily solved, nor one in respect of which there is or can be absolute certainty. There are very few, if any, questions in political economy about which entire certainty may be predicated. . . .

I do not stop to consider whether any particular view of this economic question presents the sounder theory. What the precise facts are it may be difficult to say. It is enough for the determination of this case, and it is enough for this court to know, that the question is one about which there is room for debate and for an honest difference of opinion. There are many reasons of a weighty, substantial character, based upon the experience of mankind, in support of the theory that, all things considered, more than ten hours’ steady work each day, from week to week, in a bakery or confectionery establishment, may endanger the health and shorten the lives of the workmen, thereby diminishing their physical and mental capacity to serve the state, and to provide for those dependent upon them. . . .

. . . We are not to presume that the state of New York has acted in bad faith. . . . Our duty, I submit, is to sustain the statute as not being in conflict with the federal Constitution, for the reason—and such is an all-sufficient reason—it is not shown to be plainly and palpably inconsistent with that instrument. Let the state alone in the management of its purely domestic affairs so long as it does not appear beyond all question that it has violated the federal Constitution. This view necessarily results from the principle that the health and safety of the people of a state are primarily for the state to guard and protect.

. . . A decision that the New York statute is void under the Fourteenth Amendment will, in my opinion, involve consequences of a far-reaching and mischievous character; for such a decision would seriously cripple the inherent power of the states to care for the lives, health, and well-being of their citizens. Those are matters which can be best controlled by the states. The preservation of the just powers of the states is quite as vital as the preservation of the powers of the general government. . . .

Justice HOLMES, dissenting:

I regret sincerely that I am unable to agree with the judgment in this case, and that I think it my duty to express my dissent.

This case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain. If it were a question whether I agreed with that theory, I should desire to study it further and long before making up my mind. But I do not conceive that to be my duty, because I strongly believe that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a majority to embody their opinions in law. It is settled by various decisions of this Court that state constitutions and state laws may regulate life in many ways which we, as legislators, might think as injudicious, or, if you like, as tyrannical, as this, and which, equally with this, interfere with the liberty to contract. Sunday laws and usury laws are ancient examples. A more modern one is the prohibition of lotteries. The liberty of the citizen to do as he likes so long as he does not interfere with the liberty of others to do the same, which has been a shibboleth for some well-known writers, is interfered with by school laws, by the Post Office, by every state or municipal institution which takes his money for purposes thought desirable, whether he likes it or not. The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics. The other day, we sustained the Massachusetts vaccination law.

. . . Some of these laws embody convictions or prejudices which judges are likely to share. Some may not. But a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the state or of laissez faire. It is made for people of fundamentally differing views, and the accident of our finding certain opinions natural and familiar or novel and even shocking ought not to conclude our judgment upon the question whether statutes embodying them conflict with the Constitution of the United States. . . .

Annual Message to Congress (1905)

December 05, 1905

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.