No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

As a result of its victory in the Spanish-American War (1898), the United States gained control of a number of former Spanish territories, principally Cuba and the Philippines. How to deal with these acquisitions immediately became a disputed issue. As the sermon by Henry Van Dyke and the speech by Senator Albert Beveridge show, the debate addressed long-standing, controversial and important questions, several of which had figured prominently in the crisis of the Civil War, a living and painful memory for Americans in the late nineteenth century. What authority over territories does the Constitution grant the federal government? What does the self-evident truth of equality proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence mean morally and politically? How should it guide the actions of the American government and people? Does it establish obligations between Americans and other peoples?

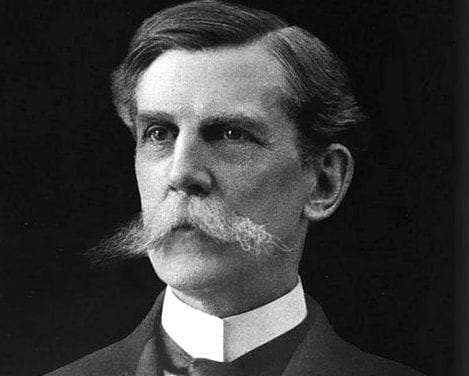

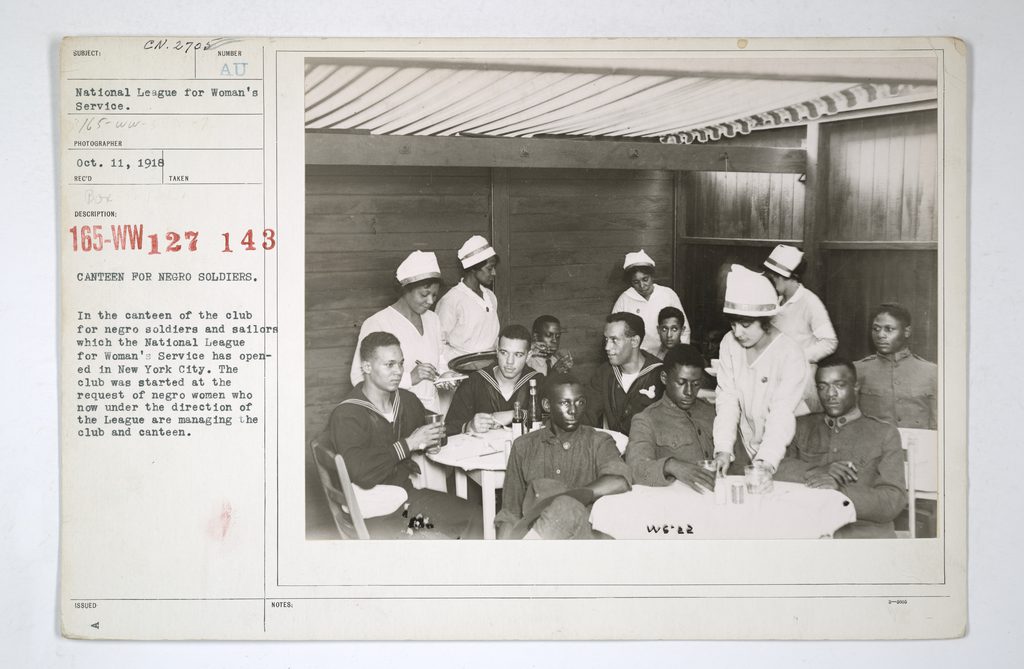

Despite their disagreement over what to do with the Philippines and the consequences of that decision for America and its people, Van Dyke and Beveridge agreed on several points. Both believed in progress and that America was a progressive nation. Both believed that there were races inferior to Americans or, more specifically, to the Anglo-Saxons whose ancestors they credited with developing the political ideals that informed the American Founding. Both saw America as a Christian nation carrying out God’s plan. (Such attitudes remained part of the way Americans thought about foreign affairs in the decades following the Spanish American War. See illustration on page 138.) These shared views, distinctive of the movement we call Progressivism (Beveridge was a leading Progressive), make their disagreement over the Philippines all the more instructive. Above all, their common appeal to but disagreement about the Declaration and the Constitution – above all the Declaration – deserves careful attention.

Documents in this chapter are available separately by following the hyperlinks below:

A. Henry Van Dyke, The American Birthright and the Philippine Pottage, November 24, 1898

Discussion Questions

A. How would you describe the differences between Van Dyke and Beveridge? Why did one want to maintain control of the Philippines and the other not? How did they differ over the interpretation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution? Does the idea of a “living Constitution,” as Beveridge puts it, have any potential limitations? Did Beveridge and Van Dyke have different understandings of self-government? If so, which one was right?

B. Is there a connection between thinking there are “inferior races,” an opinion shared by Van Dyke and Beveridge, and the treatment of Carrie Buck (Chapter 19)? Is there a connection between such thinking and the discussion of civil rights for freedmen following the Civil War (Chapter 16)?

C. In what ways do the arguments for and against the Mexican-American War in Volume 1, Chapter 13 compare with the arguments for and against the Spanish-American War?

A. Henry Van Dyke, The American Birthright and the Philippine Pottage, November 24, 1898

A Word of Explanation To the Hasty Reader

Please do not mistake the purpose of this sermon. . . .

The sermon is against the assumption that the only way to meet our responsibilities is to annex the Philippine Islands as a permanent portion of our national domain.

It is against the abandonment of the American ideal of national growth for the European ideal of colonial conquest.

It is against the theory that it is our duty to take a share in the forcible division of the territories of the Eastern peoples, instead of using our influence for their protection and their native growth into free and intelligent States like Japan.

It is against the extension of the American frontier, by the sword, to the China Sea.

It is dead against imperialism.

It is in favor of republicanism as held and taught by the authors of the Declaration of Independence. . . .

__________________

Hebrews 12:16. “Esau, who for one morsel of meat sold his birthright.”

This is the most important Thanksgiving Day that has been celebrated by the present generation of Americans. Three and thirty years have rolled away since we gave thanks for the ending of the Civil War. Never since that time has our national religious festival been observed under such brilliant sunlight of prosperity or with such portentous clouds of danger massed along the horizon.

It is a significant Thanksgiving because we have extraordinary causes for national gratitude. The first and greatest of these causes is the superabundant harvest with which, for the second year in succession, God has rewarded the patient toilers who are the strength and pride of our country. . . .

The second cause for gratitude to-day is the new evidence that we have received of the union of the whole American people in loyalty and patriotism. The gaping wounds left by the Civil War have closed. . . .

The third cause for gratitude is the renewal of cordial amity between the two leading nations of the world – Great Britain and the United States. . . .

The fourth cause for thanksgiving to-day is the signal victory that has been granted to our country’s arms in a war undertaken for the destruction of the ancient Spanish tyranny in the Western Hemisphere and the liberation of the oppressed people of Cuba. How reluctantly the American people took up the cross of war after thirty-three years of peace none can know except those who have read the peace-loving heart of the great silent classes, the happy, industrious, prosperous classes, of our country. The call of humanity was the only summons that could have roused them; the cause of liberty was the only cause for which they would have fought. No party, no administration could have received the loyal support of the whole people unless it had written on its banner the splendid motto: “Not for gain, not for territory, but for freedom and human brotherhood!” That avowal alone made the war possible and successful. For that cause alone Christians could pray with a sincere heart, and mothers give their sons to death by slaughter or disease, and lovers of liberty take up the unselfish sword. . . . [P]roud and glad of all that American soldiers and sailors have done this year in the cause of liberty, we present our offerings upon the solemn altar of gratitude. For the Divine guidance and protection, without which a victory so complete and swift, even over an inferior foe, could never have been won, let us give most humble and hearty thanks.

But this Thanksgiving Day is not significant alone in its causes for gratitude. It is an important day, a marked day, an immensely serious day because it finds us, suddenly and without preparation, face to face with the most momentous and far-reaching problem of our national history. . . . Can we fix the hanging periods?

Are the United States to continue as a peaceful republic, or are they to become a conquering empire? Is the result of the war with Spain to be the banishment of European tyranny from the Western Hemisphere, or is it to be the entanglement of the Western republic in the rivalries of European kingdoms? Have we set the Cubans free, or have we lost our own faith in freedom? Are we still loyal to the principles of our forefathers, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, or are we now ready to sell the American birthright for a mess of pottage in the Philippines? . . .

. . . There is an old-fashioned document called the American Constitution which was expressly constructed to discourage the unconscious humor of such sudden changes. Before the die is cast the people must be taken fairly into the game; before the result is irrevocable the Supreme Court must pass upon the rules and the play. The question whether the American birthright is to be bartered for the Philippine pottage is still open. A brief, preliminary discussion of this question will not be out of place this morning. . . .

The proposal to annex, by force, or purchase, or forcible purchase, these distant, unwilling and semi-barbarous islands is hailed as a new and glorious departure in American history. A new word – imperialism – has been coined to define it. It is frankly confessed that it involves a departure from ancient traditions; it is openly boasted that it leaves the counsels of Washington and Jefferson far behind us forever. Because of this novelty, because of this separation from what we once counted a most precious heritage, I venture to ask whether this bargain offers any fit compensation for the loss of our American birthright?

I. Let us consider the arguments in favor of it. They may be summed up under three heads: the argument from duty, the argument from destiny, and the argument from desperation.

1. The argument from duty comes first because it is the strongest with honest and conscientious men. Undoubtedly we have incurred responsibilities by the late war, and we must meet them in a manly spirit; but certainly these responsibilities are not unlimited. They are bounded on one side by our rights. The very question at issue is whether we have a right to deny the principles of our constitution by conquering unwilling subjects and annexing tributary colonies to our domain. On the other side our responsibilities are bounded by our abilities. It is never a duty to attempt a task which there is no prospect of performing with real usefulness. We surely owe the Filipinos the very best we can give them consistently with our other responsibilities; but it is far from being certain that the best thing we can do for them is to make them our vassals. If that were true our whole duty would not be done, the humane results of the war would not be completed, until we had annexed the misgoverned Spaniards of Spain also. No argument drawn from our duty to an oppressed and suffering race can be applied to the conquest of the Philippine Islands which does not apply with equal and even with greater force to the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

2. The argument from destiny is not an argument; it is a phrase. It takes for granted all that is in dispute; it clothes itself in glittering rainbows and introduces the question of debate in the disguise of a fact accomplished. “Yesterday,” says a brilliant orator, “there were four great nations ruling the world and dividing up the territories of barbarous tribes – Great Britain, Russia, France and Germany – to-day there are five, for America has entered the arena of colonial conquest.” But how came the great republic in that strange co-partnership? By what device was she led blindfold into that curious company? What does she there? What must she forfeit to obtain her share in the partition of spoils? That is the question. To talk of destiny is not to discuss, but to dodge, the point at issue.

3. The argument from desperation directly contradicts the argument from destiny. It presents the annexation of the Philippines, not as a glorious accomplishment, but as a hard necessity. We must do it because there is nothing else that we can do. A speaker less brilliant than the orator of the five nations, but more cautious, puts the case in a sentence: “We have got a wolf by the ears and we can’t let go.”

The answer to this is simple. We have not got the wolf at present, though we are trying our best to get hold of him. It is absurd to say that the only way for us to get out of our difficulties is to go into the enterprise of wolf-keeping. Nothing has yet been said or done which binds us to take permanent possession of these islands. Granting that the Philippines need a strong hand to set them in order, it has not been shown that ours is the only hand, nor that we must do it all alone. A protectorate for a limited time and with the purpose of building up a firm self-government would be one of the possible solutions of the difficulty. To pass this by and say that our only resort is to assume sovereignty of these yet unconquered islands is merely to beg the question.

No, these contradictory arguments from duty and destiny and despair do not touch the real spring of the movement for colonial expansion. It is the prospect of profit that makes those distant islands gleam before our fancy as desirable acquisitions. The argument drawn from the supposed need of creating and fortifying new outlets for our trade has the most practical force. It is the unconscious desire of rivaling England in her colonial wealth and power that allures us to the untried path of conquest; and this in spite of the fact that during the last seven years, England, with all her colonies, has lost five per cent of her export trade, while the United States, without colonies, have gained eighteen per cent. It is a secret discontent with the part of a peaceful, industrious, self-contained nation that urges us to take an armed hand in the partition of the East and exchange our birthright for a mess of pottage.

II. Let us weigh the arguments against such a course.

1. It is contrary to the Constitution of the United States as interpreted by the Supreme Court. The authority of that magnificent tribunal in which the Anglo-Saxon ideal of the supremacy of law is forever embodied, more clearly and powerfully than in any other human institution, is clearly against the legitimacy of a policy of colonial expansion for this republic as now constituted. “There is certainly no power given by the constitution to the federal government to establish or maintain colonies bordering on the United States or at a distance, to be ruled and governed at its own pleasure. . . . No power is given to acquire a territory to be held and governed permanently in that character. . . .”

2. Every following step in the career of colonial imperialism will bring us into conflict with our own institutions and necessitate constitutional change or insure practical failure. Our Government, with its checks and balances, with its prudent and conservative divisions of power, is the best in the world for peace and self-defense; but the worst in the world for what the President called, a few months ago, “criminal aggression.” We cannot compete with monarchies and empires in the game of land-grabbing and vassal ruling. We have not the machinery; and we cannot get it, except by breaking up our present system of government and building a new fabric out of the pieces. Republics have not been successful as rulers of colonies. When they have entered that career they have changed quickly into monarchies or empires. The supposed analogy between England and America is a fatal illusion. British institutions are founded, as Gladstone has said, on the doctrine of inequality; American institutions are founded on the doctrine of equality. If we become a colonizing power we must abandon our institutions or be paralyzed by them. The swiftness of action, the secrecy, not to say slipperiness of policy, and the absolutism of control which are essential to success in territorial conquest and dominion are inconsistent with republicanism as America has interpreted it. Imperialism and democracy, militarism and self-government are contradictory terms. A government of the people, by the people, for the people is impregnable for defense, but impotent for conquest. When imperialism comes in at the door democracy flies out at the window. An imperialistic democracy is an impossible hybrid; we might as well speak of an atheistic religion, or a white blackness. To enter upon a career of colonial expansion with our present institutions is to court failure or to prepare for silent revolution.

3. There is an equally serious objection to the attempt to launch the United States upon the business of acquiring vassal colonies and governing distant and inferior races, in the poor outfit of our people for such a task.

It is said that we must begin or we shall never learn; the trouble is that we have already begun, but we have not learned. I am not speaking now in the spirit of pessimism or despair of the American people. No man could have a more profound confidence in their native ability, their fundamental integrity, and their ultimate common sense. It is to this common sense that I would appeal for a candid judgment of our preparation for an imperial career at the present moment.

Let us be on our guard against the flattering comparison with England. The English people have a natural genius for governing inferior races – a steady head, an inflexible hand, and a superb self-confidence. What proof have we given of any such extraordinary genius in our dealing with inferior races? Does the comparison of the treatment of the Indians in Canada and in the United States give us a comfortable sense of pride? Is the condition of drunken and disorderly Alaska a just encouragement to larger enterprises? Is our success in treating the Chinese problem and the Negro problem so notorious that we must attempt to repeat it on a magnified scale eight thousand miles away? The rifle-shots that ring from Illinois and the Carolinas, announcing a bloody skirmish of races in the very heart of the republic – are these the joyous salutes that herald our advance to rule eight millions more of black and yellow people in the islands of the Pacific Ocean?

England has a magnificent Civil Service at the foundation of her colonial empire. What have we? A recently unstarched Civil Service in New York, a Civil Service in Washington which is threatened with a new and serious crippling, and a persistent endemic of boss-rule all over the country. These things are not good guarantees that we shall send our best, our cleanest, our most educated young men to fill the offices in our distant colonies. And even if we could be sure that such men would be sent, they are more needed at home than they are abroad. We have no such domestic surplus of men and deficit of work as England has. Her tiny territory and immense population mark her necessity, even as our immense territory, not yet fully peopled nor wisely ruled, marks ours. For a country in our position to set out upon the adventure of colonial conquest promises discredit to ourselves and discomfort to our vassals. With our unsolved problems staring us in the face, our cities misgoverned and our territories neglected, the cry of to-day – not the cry of despair, but the cry of hope and courage – must be “Americans for America!”

4. Another weighty argument against the annexation of the Philippines is the frightful burden which it will almost certainly impose upon the people.

First, a burden of military service. . . . [T]he ranks must be kept full; and if Americans do not thirst for garrison duty in the tropics they must be compelled or bought to serve. On the one hand we see a system of conscription like that of Germany, where every man-child is born with a soldier’s collar around his neck; on the other hand, we see an enormous drain upon the earnings of the people, like England’s annual budget of $203,000,000 for the army and navy.

Second, a burden of heavy taxation. . . .

Third, a burden of interminable and bloody strife. Expansion means entanglement; entanglement means ultimate conflict. The great nations of Europe are encamped around the China Sea in arms. If we go in among them we must fight when they blow the trumpet. . . .

. . . Colonial expansion means coming strife; the annexation of the Philippines means the annexation of a new danger to the world’s peace. The acceptance of imperialism means that we must prepare to beat our ploughshares into swords and our pruning hooks into spears, and be ready to water distant lands and stain foreign seas with an ever-increasing torrent of American blood. Is it for this that philanthropists and Christian preachers urge us to abandon our peaceful mission of enlightenment and thrust forward, sword in hand, into the arena of imperial conflict?

5. But the chief argument against the forcible extension of American sovereignty over the Philippines is that it certainly involves the surrender of our American birthright of glorious ideals. “This imitation of Old World methods,” said one of our most powerful journals, a few months ago, “by the New World appears to us to be based upon an entire disregard, not merely of American precedence, but of American principles.”

I do not speak now of our word of honor, tacitly pledged to the world, when we disclaimed “Any Disposition Or Intention To Exercise Any Sovereignty, Jurisdiction Or Control Over Said Islands, Except For The Pacification Thereof.” . . . Pass it by.

But how can we pass by the solemn and majestic claim of our Declaration of Independence, that “Government derives its just powers from the consent of the governed?” How can we abandon the principle for which our fathers fought and died: “No taxation without representation?” . . .

Anonymous patriots have written to warn me that it is a dangerous task to call for this discussion. It imperils popularity. The cry of to-day is: “Wherever the American flag has been raised it never must be hauled down.” The man who will not join that cry may be accused of disloyalty and called a Spaniard. So be it, then. If the price of popularity is the stifling of conviction, I want none of it. If the test of loyalty is to join in every thoughtless cry of the multitude, I decline it. I profess a higher loyalty – allegiance to the flag, not for what it covers, but for what it means.

There is one thing that can happen to the American flag worse than to be hauled down. That is to have its meaning and its message changed.

Hitherto it has meant freedom, and equality, and self-government, and battle only for the sake of peace. Pray God its message may never be altered. . . .

God save the birthright of the one country on earth whose ideal is not to subjugate the world but to enlighten it.

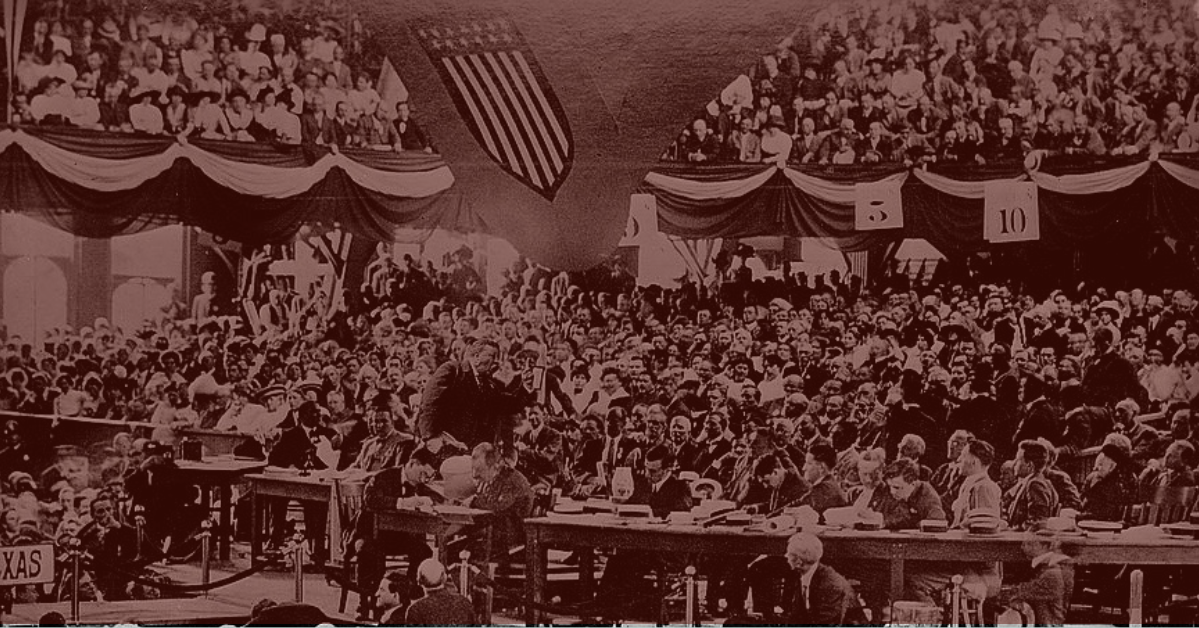

B. Senator Albert J. Beveridge, Speech in the Senate in Support of an American Empire, January 9, 1900

MR. PRESIDENT, the times call for candor. The Philippines are ours forever, “territory belonging to the United States,” as the Constitution calls them. And just beyond the Philippines are China’s illimitable markets. We will not retreat from either. We will not repudiate our duty in the archipelago. We will not abandon our opportunity in the Orient. We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world. And we will move forward to our work, not howling out regrets like slaves whipped to their burdens but with gratitude for a task worthy of our strength and thanksgiving to Almighty God that He has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world.

This island empire is the last land left in all the oceans. If it should prove a mistake to abandon it, the blunder once made would be irretrievable. If it proves a mistake to hold it, the error can be corrected when we will. Every other progressive nation stands ready to relieve us.

But to hold it will be no mistake. Our largest trade henceforth must be with Asia. The Pacific is our ocean. More and more Europe will manufacture the most it needs, secure from its colonies the most it consumes. Where shall we turn for consumers of our surplus? Geography answers the question. China is our natural customer. She is nearer to us than to England, Germany, or Russia, the commercial powers of the present and the future. They have moved nearer to China by securing permanent bases on her borders. The Philippines give us a base at the door of all the East.

Lines of navigation from our ports to the Orient and Australia, from the Isthmian Canal to Asia, from all Oriental ports to Australia converge at and separate from the Philippines. They are a self-supporting, dividend-paying fleet, permanently anchored at a spot selected by the strategy of Providence, commanding the Pacific. And the Pacific is the ocean of the commerce of the future. Most future wars will be conflicts for commerce. The power that rules the Pacific, therefore, is the power that rules the world. And, with the Philippines, that power is and will forever be the American Republic. . . .

But if they did not command China, India, the Orient, the whole Pacific for purposes of offense, defense, and trade, the Philippines are so valuable in themselves that we should hold them. I have cruised more than 2,000 miles through the archipelago, every moment a surprise at its loveliness and wealth. I have ridden hundreds of miles on the islands, every foot of the way a revelation of vegetable and mineral riches. . . .

Here, then, senators, is the situation. Two years ago there was no land in all the world which we could occupy for any purpose. Our commerce was daily turning toward the Orient, and geography and trade developments made necessary our commercial empire over the Pacific. And in that ocean we had no commercial, naval, or military base. Today, we have one of the three great ocean possessions of the globe, located at the most commanding commercial, naval, and military points in the Eastern seas, within hail of India, shoulder to shoulder with China, richer in its own resources than any equal body of land on the entire globe, and peopled by a race which civilization demands shall be improved. Shall we abandon it?

That man little knows the common people of the republic, little understands the instincts of our race who thinks we will not hold it fast and hold it forever, administering just government by simplest methods. We may trick up devices to shift our burden and lessen our opportunity; they will avail us nothing but delay. We may tangle conditions by applying academic arrangements of self-government to a crude situation; their failure will drive us to our duty in the end. . . .

. . . This war is like all other wars. It needs to be finished before it is stopped. I am prepared to vote either to make our work thorough or even now to abandon it. A lasting peace can be secured only by overwhelming forces in ceaseless action until universal and absolutely final defeat is inflicted on the enemy. To halt before every armed force, every guerrilla band opposing us is dispersed or exterminated will prolong hostilities and leave alive the seeds of perpetual insurrection.

Even then we should not treat. To treat at all is to admit that we are wrong. And any quiet so secured will be delusive and fleeting. And a false peace will betray us; a sham truce will curse us. It is not to serve the purposes of the hour, it is not to salve a present situation that peace should be established. It is for the tranquility of the archipelago forever. It is for an orderly government for the Filipinos for all the future. It is to give this problem to posterity solved and settled, not vexed and involved. It is to establish the supremacy of the American republic over the Pacific and throughout the East till the end of time.

It has been charged that our conduct of the war has been cruel. Senators, it has been the reverse. I have been in our hospitals and seen the Filipino wounded as carefully, tenderly cared for as our own. Within our lines they may plow and sow and reap and go about the affairs of peace with absolute liberty. And yet all this kindness was misunderstood, or rather not understood. Senators must remember that we are not dealing with Americans or Europeans. We are dealing with Orientals. We are dealing with Orientals who are Malays. We are dealing with Malays instructed in Spanish methods. They mistake kindness for weakness, forbearance for fear. It could not be otherwise unless you could erase hundreds of years of savagery, other hundreds of years of Orientalism, and still other hundreds of years of Spanish character and custom. . . .

Mr. President, reluctantly and only from a sense of duty am I forced to say that American opposition to the war has been the chief factor in prolonging it. Had Aguinaldo not understood that in America, even in the American Congress, even here in the Senate, he and his cause were supported; had he not known that it was proclaimed on the stump and in the press of a faction in the United States that every shot his misguided followers fired into the breasts of American soldiers was like the volleys fired by Washington’s men against the soldiers of King George, his insurrection would have dissolved before it entirely crystalized. . . .

. . . It is believed and stated in Luzon, Panay, and Cebu that the Filipinos have only to fight, harass, retreat, break up into small parties, if necessary, as they are doing now, but by any means hold out until the next presidential election, and our forces will be withdrawn.

All this has aided the enemy more than climate, arms, and battle. Senators, I have heard these reports myself; I have talked with the people; I have seen our mangled boys in the hospital and field; I have stood on the firing line and beheld our dead soldiers, their faces turned to the pitiless southern sky, and in sorrow rather than anger I say to those whose voices in America have cheered those misguided natives on to shoot our soldiers down, that the blood of those dead and wounded boys of ours is on their hands, and the flood of all the years can never wash that stain away. In sorrow rather than anger I say these words, for I earnestly believe that our brothers knew not what they did.

But, senators, it would be better to abandon this combined garden and Gibraltar of the Pacific, and count our blood and treasure already spent a profitable loss than to apply any academic arrangement of self-government to these children. They are not capable of self-government. How could they be? They are not of a self-governing race. They are Orientals, Malays, instructed by Spaniards in the latter’s worst estate.

They know nothing of practical government except as they have witnessed the weak, corrupt, cruel, and capricious rule of Spain. What magic will anyone employ to dissolve in their minds and characters those impressions of governors and governed which three centuries of misrule has created? What alchemy will change the Oriental quality of their blood and set the self-governing currents of the American pouring through their Malay veins? How shall they, in the twinkling of an eye, be exalted to the heights of self-governing peoples which required a thousand years for us to reach, Anglo-Saxon though we are?

Let men beware how they employ the term “self-government.” It is a sacred term. It is the watchword at the door of the inner temple of liberty, for liberty does not always mean self-government. Self-government is a method of liberty – the highest, simplest, best – and it is acquired only after centuries of study and struggle and experiment and instruction and all the elements of the progress of man. Self-government is no base and common thing to be bestowed on the merely audacious. It is the degree which crowns the graduate of liberty, not the name of liberty’s infant class, who have not yet mastered the alphabet of freedom. Savage blood, Oriental blood, Malay blood, Spanish example—are these the elements of self-government?

We must act on the situation as it exists, not as we would wish it. . . .

. . . [W]e must never forget that in dealing with the Filipinos we deal with children.

And so our government must be simple and strong. Simple and strong! . . .

Mr. President, self-government and internal development have been the dominant notes of our first century; administration and the development of other lands will be the dominant notes of our second century. And administration is as high and holy a function as self-government, just as the care of a trust estate is as sacred an obligation as the management of our own concerns. Cain was the first to violate the divine law of human society which makes of us our brother’s keeper. And administration of good government is the first lesson in self-government, that exalted estate toward which all civilization tends.

Administration of good government is not denial of liberty. For what is liberty? It is not savagery. It is not the exercise of individual will. It is not dictatorship. It involves government, but not necessarily self-government. It means law. First of all, it is a common rule of action, applying equally to all within its limits. Liberty means protection of property and life without price, free speech without intimidation, justice without purchase or delay, government without favor or favorites. What will best give all this to the people of the Philippines – American administration, developing them gradually toward self-government, or self-government by a people before they know what self-government means?

The Declaration of Independence does not forbid us to do our part in the regeneration of the world. If it did, the Declaration would be wrong, just as the Articles of Confederation, drafted by the very same men who signed the Declaration, was found to be wrong. The Declaration has no application to the present situation. It was written by self-governing men for self-governing men. It was written by men who, for a century and a half, had been experimenting in self-government on this continent, and whose ancestors for hundreds of years before had been gradually developing toward that high and holy estate.

The Declaration applies only to people capable of self-government. How dare any man prostitute this expression of the very elect of self-governing peoples to a race of Malay children of barbarism, schooled in Spanish methods and ideas? And you who say the Declaration applies to all men, how dare you deny its application to the American Indian? And if you deny it to the Indian at home, how dare you grant it to the Malay abroad?

The Declaration does not contemplate that all government must have the consent of the governed. It announces that man’s “inalienable rights are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are established among men deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that when any form of government becomes destructive of those rights, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it.” “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are the important things; “consent of the governed” is one of the means to those ends.

If “any form of government becomes destructive of those ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it,” says the Declaration. “Any forms” includes all forms. Thus the Declaration itself recognizes other forms of government than those resting on the consent of the governed. The word “consent” itself recognizes other forms, for “consent” means the understanding of the thing to which the “consent” is given; and there are people in the world who do not understand any form of government. And the sense in which “consent” is used in the Declaration is broader than mere understanding; for “consent” in the Declaration means participation in the government “consented” to. And yet these people who are not capable of “consenting” to any form of government must be governed.

And so the Declaration contemplates all forms of government which secure the fundamental rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Self-government, when that will best secure these ends, as in the case of people capable of self-government; other appropriate forms when people are not capable of self-government. And so the authors of the Declaration themselves governed the Indian without his consent; the inhabitants of Louisiana without their consent; and ever since the sons of the makers of the Declaration have been governing not by theory but by practice, after the fashion of our governing race, now by one form, now by another, but always for the purpose of securing the great eternal ends of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, not in the savage but in the civilized meaning of those terms – life, according to orderly methods of civilized society; liberty regulated by law; pursuit of happiness limited by the pursuit of happiness by every other man.

If this is not the meaning of the Declaration, our government itself denies the Declaration every time it receives the representative of any but a republican form of government, such as that of the sultan, the czar, or other absolute autocrats, whose governments, according to the opposition’s interpretation of the Declaration, are spurious governments because the people governed have not “consented” to them.

Senators in opposition are estopped from denying our constitutional power to govern the Philippines as circumstances may demand, for such power is admitted in the case of Florida, Louisiana, Alaska. How, then, is it denied in the Philippines? Is there a geographical interpretation to the Constitution? Do degrees of longitude fix constitutional limitations? Does a thousand miles of ocean diminish constitutional power more than a thousand miles of land?

The ocean does not separate us from the field of our duty and endeavor. . . .

There is in the ocean no constitutional argument against the march of the flag, for the oceans, too, are ours. . . . [T]he shores of all the continents calling us, the Great Republic before I die will be the acknowledged lord of the world’s high seas. And over them the republic will hold dominion, by virtue of the strength God has given it, for the peace of the world and the betterment of man.

No; the oceans are not limitations of the power which the Constitution expressly gives Congress to govern all territory the nation may acquire. The Constitution declares that “Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory belonging to the United States.” Not the Northwest Territory only; not Louisiana or Florida only; not territory on this continent only but any territory anywhere belonging to the nation.

The founders of the nation were not provincial. Theirs was the geography of the world. They were soldiers as well as landsmen, and they knew that where our ships should go our flag might follow. They had the logic of progress, and they knew that the republic they were planting must, in obedience to the laws of our expanding race, necessarily develop into the greater republic which the world beholds today, and into the still mightier republic which the world will finally acknowledge as the arbiter, under God, of the destinies of mankind. And so our fathers wrote into the Constitution these words of growth, of expansion, of empire, if you will, unlimited by geography or climate or by anything but the vitality and possibilities of the American people: “Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory belonging to the United States.”

The power to govern all territory the nation may acquire would have been in Congress if the language affirming that power had not been written in the Constitution; for not all powers of the national government are expressed. Its principal powers are implied. The written Constitution is but the index of the living Constitution. Had this not been true, the Constitution would have failed; for the people in any event would have developed and progressed. And if the Constitution had not had the capacity for growth corresponding with the growth of the nation, the Constitution would and should have been abandoned as the Articles of Confederation were abandoned. For the Constitution is not immortal in itself, is not useful even in itself. The Constitution is immortal and even useful only as it serves the orderly development of the nation. The nation alone is immortal. The nation alone is sacred. The Army is its servant. The Navy is its servant. The President is its servant. This Senate is its servant. Our laws are its methods. Our Constitution is its instrument. . . .

Mr. President, this question is deeper than any question of party politics; deeper than any question of the isolated policy of our country even; deeper even than any question of constitutional power. It is elemental. It is racial. God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration. No! He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns. He has given us the spirit of progress to overwhelm the forces of reaction throughout the earth. He has made us adepts in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples. Were it not for such a force as this the world would relapse into barbarism and night. And of all our race He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man. We are trustees of the world’s progress, guardians of its righteous peace. The judgment of the Master is upon us: “Ye have been faithful over a few things; I will make you ruler over many things.”

What shall history say of us? Shall it say that we renounced that holy trust, left the savage to his base condition, the wilderness to the reign of waste, deserted duty, abandoned glory, forgot our sordid profit even, because we feared our strength and read the charter of our powers with the doubter’s eye and the quibbler’s mind? Shall it say that, called by events to captain and command the proudest, ablest, purest race of history in history’s noblest work, we declined that great commission? Our fathers would not have had it so. No! They founded no paralytic government, incapable of the simplest acts of administration. They planted no sluggard people, passive while the world’s work calls them. They established no reactionary nation. They unfurled no retreating flag.

That flag has never paused in its onward march. Who dares halt it now – now, when history’s largest events are carrying it forward; now, when we are at last one people, strong enough for any task, great enough for any glory destiny can bestow? How comes it that our first century closes with the process of consolidating the American people into a unit just accomplished, and quick upon the stroke of that great hour presses upon us our world opportunity, world duty, and world glory, which none but the people welded into an invisible nation can achieve or perform?

Blind indeed is he who sees not the hand of God in events so vast, so harmonious, so benign. Reactionary indeed is the mind that perceives not that this vital people is the strongest of the saving forces of the world; that our place, therefore, is at the head of the constructing and redeeming nations of the earth; and that to stand aside while events march on is a surrender of our interests, a betrayal of our duty as blind as it is base. Craven indeed is the heart that fears to perform a work so golden and so noble; that dares not win a glory so immortal. . . .

. . . Pray God the time may never come when Mammon and the love of ease shall so debase our blood that we will fear to shed it for the flag and its imperial destiny. Pray God the time may never come when American heroism is but a legend like the story of the Cid, American faith in our mission and our might a dream dissolved, and the glory of our mighty race departed.

And that time will never come. We will renew our youth at the fountain of new and glorious deeds. We will exalt our reverence for the flag by carrying it to a noble future as well as by remembering its ineffable past. Its immortality will not pass, because everywhere and always we will acknowledge and discharge the solemn responsibilities our sacred flag, in its deepest meaning, puts upon us. And so, senators, with reverent hearts, where dwells the fear of God, the American people move forward to the future of their hope and the doing of His work. . . .

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.