Introduction

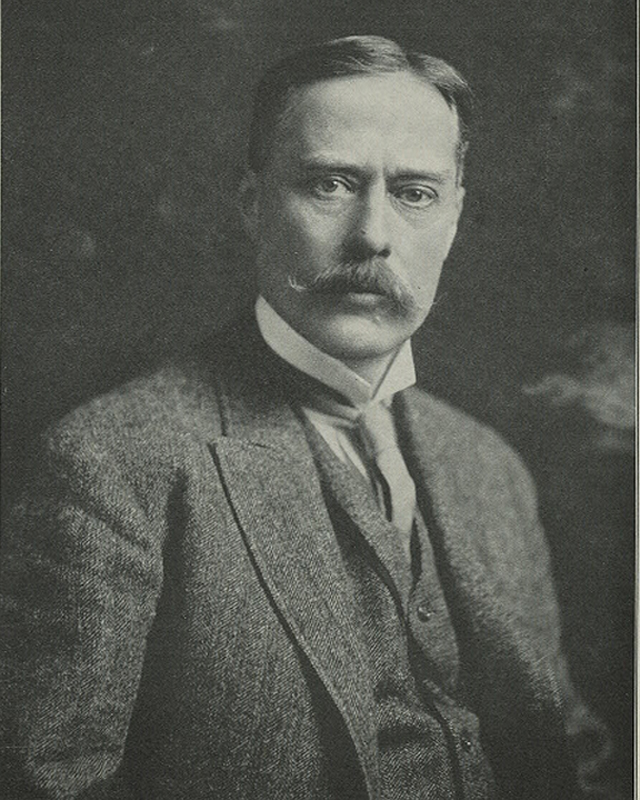

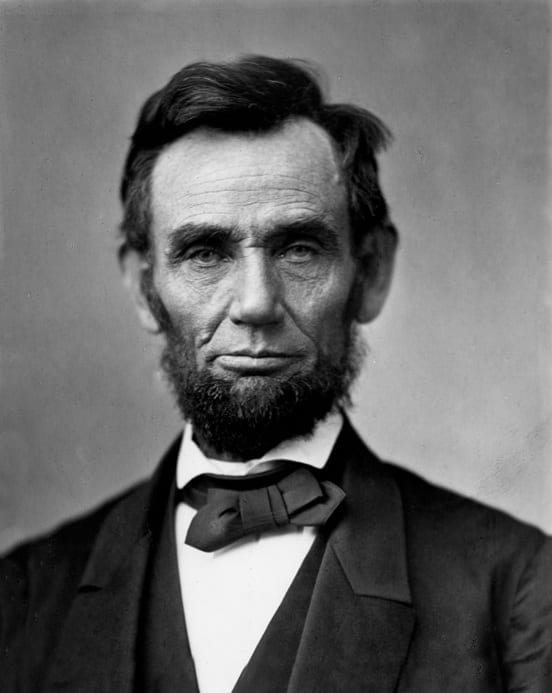

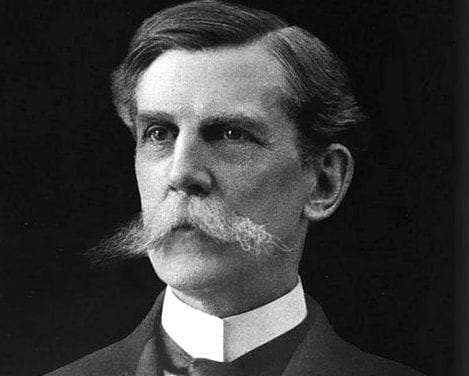

Frank Johnson Goodnow (1859–1939) was an accomplished scholar who taught at Columbia University and served as the first president of the American Political Science Association. A leading Progressive theorist, Goodnow’s scholarship influenced the Progressive movement during the early part of the twentieth century. In the first chapter of Politics and Administration, from which this document was drawn, Goodnow described the two different functions of government— politics and administration—and the subjects that fall within each. Although the Constitution divided governmental powers into three separate entities—executive, legislative, and judiciary—Goodnow argued that there were only two types of powers: making laws and executing them. Further, he claimed that the Constitution carried the separation of powers too far, making the effective operation of the government impossible. In place of the three-part separation of powers Goodnow offered a two-part division, with significant overlap between the power to make the law and the power to carry it out. This new view laid the groundwork for new administrative agencies that would put rule-making, executive, and adjudication power in the same hands.

—J. David Alvis and Joseph Postell

Frank Johnson Goodnow, Politics and Administration: A Study in Government (London: Macmillan, 1914), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112012281207. The book was published originally in 1900.

. . .[P]olitical functions group themselves naturally under two heads, which are equally applicable to the mental operations and the actions of self-conscious personalities. That is, the action of the state as a political entity consists either in operations necessary to the expression of its will, or in operations necessary to the execution of that will. The will of the state or sovereign must be made up and formulated before political action can be had. The will of the state or sovereign must be executed, after it has been formulated, if that will is to result in governmental action. All of the actions of the state or its organs, further, are undertaken with the object either of facilitating the expression of will or of aiding in its execution. This would seem to be the case whatever may be the formal character of the governmental system. . . .

The fact is, therefore, that not merely may these two functions be distinguished in all kinds of governments, but that in every government more or less differentiated organs are established. Each of these organs, while not perhaps confined exclusively to the discharge of one of these functions, is still characterized by the fact that its action consists largely or mainly in the discharge of one or the other. This is the solution of the problem of government which the human race has generally adopted. It is a solution, further, which is inevitable both because of psychological necessity and for reasons of economic expediency.

It is upon this fundamental distinction of governmental functions that Montesquieu’s famous theory of the separation of powers is based. In his Spirit of Laws (book XI, chap. VI) he distinguished three powers of government which he called respectively the legislative, executive, and judicial. This differentiation of three rather than two governmental functions was probably due to the fact that Montesquieu’s theory was derived very largely from a study of English institutions. . . .

Montesquieu’s theory involved, however, not merely the recognition of separate powers of functions of government, but also the existence of separate governmental authorities, to each of which one of the powers of government was to be entrusted. . . .

This theory was, as to this point, carried much further than its author would have considered proper, and in its extreme form has been proven to be incapable of application to any concrete political organization. American experience is conclusive on this point.

At the time our early constitutions, including the national Constitution, were framed, this principle of the separation of powers with its corollary, the separation of authorities, was universally accepted in this country. It was therefore with its corollary made the basis of these instruments. . . .

This principle of the separation of powers and authorities has been proven, however, to be unworkable as a legal principle. . . .The separation of authorities, notwithstanding constitutional provisions and judicial decisions and dicta1 on the general subject, must therefore be regarded as existent in our constitutional law only in an attenuated form

This is true both of American and of European constitutions. No political organization, based on the general theory of a differentiation of governmental functions has ever been established which assigns the function of expressing the will of the state exclusively to any one of the organs for which it makes provision.

Thus, the organ of government whose main function is the execution of the will of the state is often, and indeed usually, entrusted with the expression of that will in its details. These details, however, when expressed, must conform with the general principles laid down by the organ whose main duty is that of expression. That is, the authority called executive has, in almost all cases, considerable ordinance or legislative power.

On the other hand, the organ whose main duty is to express the will of the state, i.e., the legislature, has usually the power to control in one way or another the execution of the state will by that organ to which such execution is in the main entrusted. That is, while the two primary functions of government are susceptible of differentiation, the organs of government to which the discharge of these functions is entrusted cannot be clearly defined. . . .