Introduction

George Washington Plunkitt was born into poverty and received only three years of formal education, but this did not stop him from rising in the ranks of Tammany Hall, the New York Democratic political machine. A political machine, as opposed to the political party, was a party organization headed by a single boss or small group that held enough votes to maintain political and administrative control of a city, county, or state. Often these machines provided goods and social services that struggling local governments were unable to give to the people. William “Boss” Tweed, head of Tammany Hall, for example, was able to build a loyal following by performing favors for immigrant groups, such as providing jobs or securing housing.

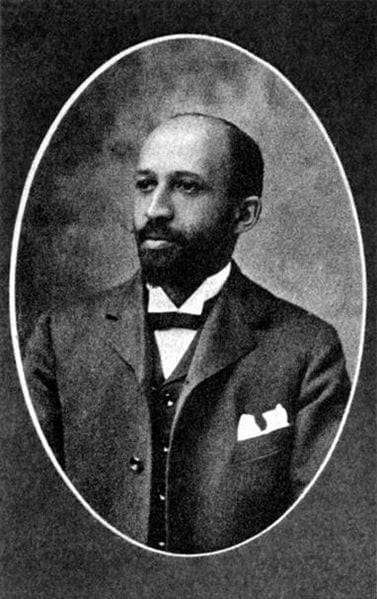

Plunkitt served as state senator and a representative to the New York Assembly, but was best known and most influential acting as a ward boss (that is, a local political party organizer) in New York’s Fifteenth Assembly District. Plunkitt built a substantial and powerful following among the working-class Irish of the district by doing political favors and providing services for the people. At the same time, he became independently wealthy by manipulating the political system and trading political favors for insider information. These practices, which Plunkitt candidly (if ironically) defended as “honest graft,” provide a close-up look at the functioning and practices of the big city machines. Plunkitt was only too happy to defend these practices against accusations of corruption and inefficiency.

Source: William Riordan, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics (New York: McClure, Philips, 1905, pp. 3-16. https://archive.org/details/plunkittoftamman0”0rior

Chapter 1: Honest Graft and Dishonest Graft

EVERYBODY is talkin’ these days about Tammany men growin’ rich on graft, but nobody thinks of drawin’ the distinction between honest graft and dishonest graft. There’s all the difference in the world between the two. Yes, many of our men have grown rich in politics. I have myself. I’ve made a big fortune out of the game, and I’m gettin’ richer every day, but I’ve not gone in for dishonest graft—blackmailin’ gamblers, saloonkeepers, disorderly people, etc.—and neither has any of the men who have made big fortunes in politics.

There’s an honest graft, and I’m an example of how it works. I might sum up the whole thing by sayin’: I seen my opportunities and I took “em.”

Just let me explain by examples. My party’s in power in the city, and it’s goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to lay out a new park at a certain place.

I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. The the board of this or that makes its plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before.

Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft.

Or, supposin’ it’s a new bridge they’re goin’ to build. I get tipped off and I buy as much property as I can that has to be taken for approaches. I sell at my own price later on and drop some more money in the bank.

Wouldn’t you? It’s just lookin’ ahead in Wall Street or in the coffee or cotton market. It’s honest graft, and I’m lookin’ for it every day in the year. I will tell you frankly that I’ve got a good lot of it, too.

I’ll tell you of one case. They were goin’ to fix up a bid park, no matter where. I got on to it, and went lookin’ about for land in that neighborhood.

I could get nothin’ at a bargain but a big piece of swamp, but I took it fast enough and held on to it. What turned out was just what I counted on. They couldn’t make the park complete without Plunkitt’s swamp, and they had to pay a good price for it. Anything dishonest in that?

Up in the watershed I made some money, too. I bought up several bits of land there some years ago and made a pretty good guess that they would be bought up for water purposes later by the city.

Somehow, I always guessed about right, and shouldn’t I enjoy the profit of my foresight? It was rather amusin’ when the condemnation commissioners came along and found piece after piece of the land in the name of George Plunkitt of the Fifteenth Assembly District, New York City. They wondered how I knew just what to buy. The answer is—I seen my opportunity and I took it. I haven’t confined myself to land; anything that pays is in my line.

For instance, the city is repavin’ a street and has several hundred thousand old granite blocks to sell. I am on hand to buy, and I know just what they are worth.

How? Never mind that. I had a sort of monopoly of this business for a while, but once a newspaper tried to do me. It got some outside men to come over from Brooklyn and New Jersey to bid against me.

Was I done? Not much. I went to each of the men and said: “How many of these 250,000 stories do you want?” One said 20,000, and another wanted 15,000, and other wanted 10,000. I said: “All right, let me bid for the lot, and I’ll give each of you all you want for nothin”.

They agreed, of course. Then the auctioneer yelled: “How much am I bid for these 250,000 fine pavin’ stones?”

“ Two dollars and fifty cents,” says I.

“ Two dollars and fifty cents!” screamed the auctioneer. “Oh, that’s a joke! Give me a real bid.”

He found the bid was real enough. My rivals stood silent. I got the lot for $2.50 and gave them their share. That’s how the attempt to do Plunkitt ended, and that’s how all such attempts end.

I’ve told you how I got rich by honest graft. Now, let me tell you that most politicians who are accused of robbin’ the city get rich the same way.

They didn’t steal a dollar from the city treasury. They just seen their opportunities and took them. That is why, when a reform administration comes in and spends a half million dollars in tryin’ to find the public robberies they talked about in the campaign, they don’t find them.

The books are always all right. The money in the city treasury is all right. Everything is all right. All they can show is that the Tammany heads of departments looked after their friends, within the law, and gave them what opportunities they could to make honest graft. Now, let me tell you that’s never goin’ to hurt Tammany with the people. Every good man looks after his friends, and any man who doesn’t isn’t likely to be popular. If I have a good thing to hand out in private life, I give it to a friend—Why shouldn’t I do the same in public life?

Another kind of honest graft. Tammany has raised a good many salaries. There was an awful howl by the reformers, but don’t you know that Tammany gains ten votes for every one it lost by salary raisin’?

The Wall Street banker thinks it shameful to raise a department clerk’s salary from $1500 to $1800 a year, but every man who draws a salary himself says: “That’s all right. I wish it was me.” And he feels very much like votin’ the Tammany[1] ticket on election day, just out of sympathy.

Tammany was beat in 1901 because the people were deceived into believin’ that it worked dishonest graft. They didn’t draw a distinction between dishonest and honest graft, but they saw that some Tammany men grew rich, and supposed they had been robbin’ the city treasury or levyin’ blackmail on disorderly houses, or workin’ in with the gamblers and lawbreakers.

As a matter of policy, if nothing else, why should the Tammany leaders go into such dirty business, when there is so much honest graft lyin’ around when they are in power? Did you ever consider that?

Now, in conclusion, I want to say that I don’t own a dishonest dollar. If my worst enemy was given the job of writin’ my epitaph when I’m gone, he couldn’t do more than write:

“George W. Plunkitt. He Seen His Opportunities, and He Took ‘Em.”

Chapter 2: How to Become a Statesman

THERE’S thousands of young men in this city who will go to the polls for the first time next November. Among them will be many who have watched the careers of successful men in politics, and who are longin’ to make names and fortunes for themselves at the same game—It is to these youths that I want to give advice. First, let me say that I am in a position to give what the courts call expert testimony on the subject. I don’t think you can easily find a better example than I am of success in politics. After forty years’ experience at the game I am—well, I’m George Washington Plunkitt. Everybody knows what figure I cut in the greatest organization on earth, and if you hear people say that I’ve laid away a million or so since I was a butcher’s boy in Washington Market, don’t come to me for an indignant denial. I’m pretty comfortable, thank you.

… Another mistake: some young men think that the best way to prepare for the political game is to practice speakin’ and becomin’ orators. That’s all wrong. We’ve got some orators in Tammany Hall, but they’re chiefly ornamental. You never heard of Charlie Murphy[2] delivering a speech, did you? Or Richard Croker,[3] or John Kelly,[4] or any other man who has been a real power in the organization? Look at the thirty-six district leaders of Tammany Hall today. How many of them travel on their tongues? Maybe one or two, and they don’t count when business is doin’ at Tammany Hall. The men who rule have practiced keepin’ their tongues still, not exercisin’ them. So you want to drop the orator idea unless you mean to go into politics just to perform the sky-rocket act.

…That was beginnin’ business in a small way, wasn’t it? But that is the only way to become a real lastin’ statesman. I soon branched out. Two young men in the flat next to mine were school friends—I went to them, just as I went to Tommy, and they agreed to stand by me. Then I had a followin’ of three voters and I began to get a bit chesty. Whenever I dropped into district head-quarters, everybody shook hands with me, and the leader one day honored me by lightin’ a match for my cigar. And so it went on like a snowball rollin’ down a hill I worked the flat-house that I lived in from the basement to the top floor, and I got about a dozen young men to follow me. Then I tackled the next house and so on down the block and around the corner. Before long I had sixty men back of me and formed the George Washington Plunkitt Association….

- 1. Tammany Hall was the Democratic political machine that controlled New York City and New York State politics through most of the nineteenth century.

- 2. Known as Silent Charlie Murphy, he was a political boss of Tammany Hall and was responsible for raising it to a level of respectability.

- 3. Known as Boss Croker, he was an Irish American politician who led Tammany Hall as a political boss.

- 4. Known as Honest John, he was a boss of Tammany Hall and a US Representative from New York from 1855 to 1858.

An Address to the Country

August 19, 1906

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.