No study questions

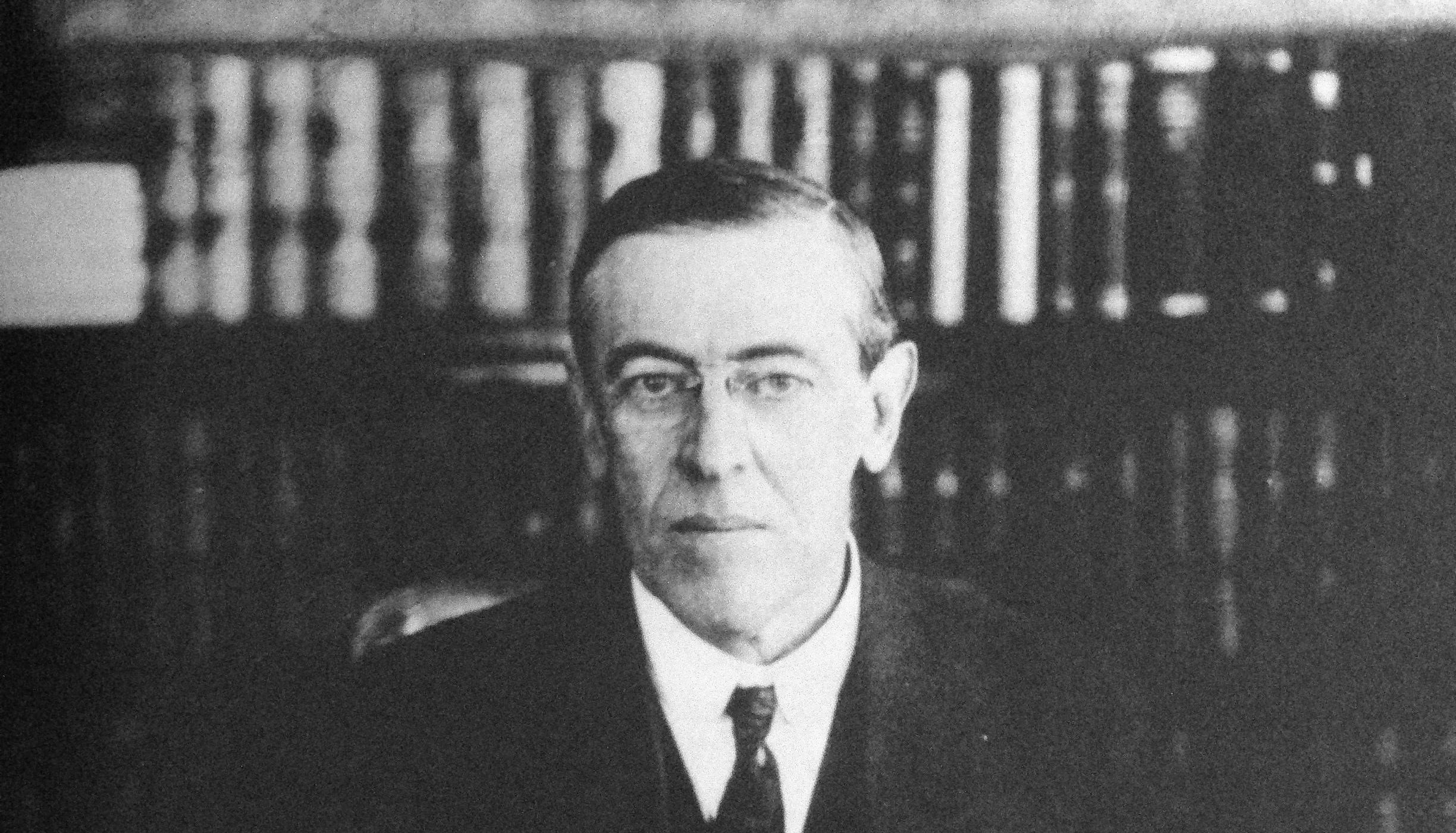

SOURCE: Woodrow Wilson, Woodrow Wilson Papers: Series 7: Speeches, Writings, and Academic Material, -1923; Subseries A: Speeches, 1882 to 1923; 1910, Nov. 5-1912, Sept. 26. November 5, 1910, 1910. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss4602900765/.

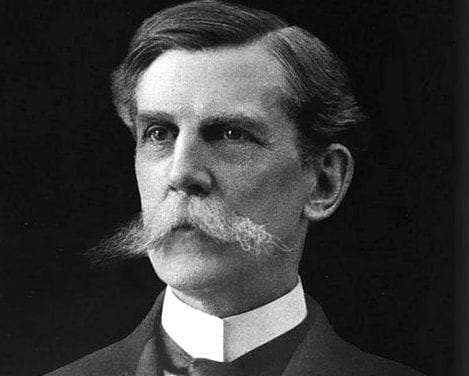

Mr. James[1] and Gentlemen of the Notification Committee:

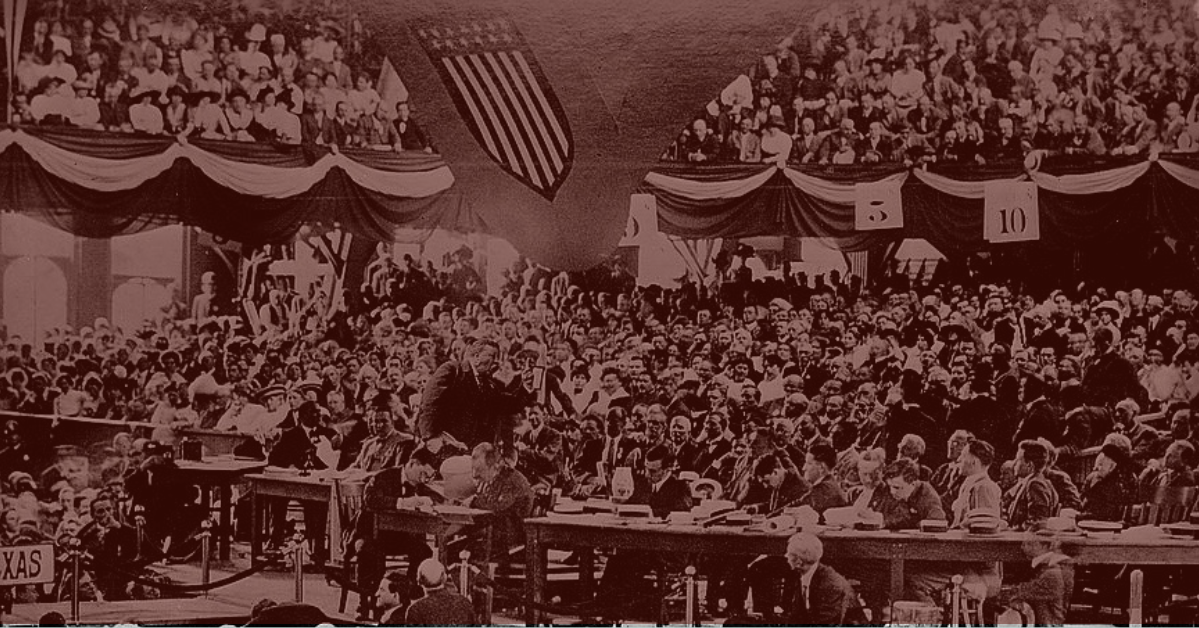

Speaking for the National Democratic Convention, recently assembled at Baltimore, you have notified me of my nomination by the Democratic Party for the high office of President of the United States. Allow me to thank you very warmly for the generous terms in which you have, through your distinguished chairman, conveyed the notification, and for the thoughtful personal courtesy with which you have performed your interesting and important errand.

I accept the nomination with a deep sense of its unusual significance and of the great honor done me, and also with a very profound sense of my responsibility to the party and to the Nation. You will expect me in accepting the honor to speak very plainly the faith that is in me. You will expect me, in brief, to talk politics and open the campaign in words whose meaning no one need doubt. You will expect me to speak to the country as well as to yourselves.

We cannot intelligently talk politics unless we know to whom we are talking and in what circumstances. The present circumstances are clearly unusual. No previous political campaign in our time has disclosed anything like them. The audience we address is in no ordinary temper. It is no audience of partisans. Citizens of every class and party and prepossession sit together, a single people, to learn whether we understand their life and know how to afford them the counsel and guidance they are now keenly aware that they stand in need of. We must speak, not to catch votes, but to satisfy the thought and conscience of a people deeply stirred by the conviction that they have come to a critical turning point in their moral and political development.

IN PRESENCE OF AN AWAKENED NATION

We stand in the presence of an awakened Nation, impatient of partisan make-believe. The public man who does not realize the fact and feel its stimulation must be singularly unsusceptible to the influences that stir in every quarter about him. The Nation has awakened to a sense of neglected ideals and neglected duties; to a consciousness that the rank and file of her people find life very hard to sustain, that her young men find opportunity embarrassed, and that her older men find business difficult to renew and maintain because of circumstances of privilege and private advantage which have interlaced their subtle threads throughout almost every part of the framework of our present law. She has awakened to the knowledge that she has lost certain cherished liberties and has wasted priceless resources which she had solemnly undertaken to hold in trust for posterity and for all mankind; and to the conviction that she stands confronted with an occasion for constructive statesmanship such as has not arisen since the great days in which her Government was set up.

Plainly, it is a new age. . . .

GREAT QUESTIONS OF RIGHT AND JUSTICE

It is in the broad light of this new day that we stand face to face—with what? Plainly not with questions of party, not with a contest for office, not with a petty struggle for advantage, Democrat against Republican, liberal against conservative, progressive against reactionary. With great questions of right and of justice, rather questions of national development, of the development of character and of standards of action no less than of a better business system, more free, more equitable, more open to ordinary men, practicable to live under, tolerable to work under, or a better fiscal system whose taxes shall not come out of the pockets of the many to go into the pockets of the few, and within whose intricacies special privilege may not so easily find covert. The forces of the Nation are asserting themselves against every form of special privilege and private control, and are seeking bigger things than they have ever heretofore achieved. They are sweeping away what is unrighteous in order to vindicate once more the essential rights of human life; and, what is very serious for us, they are looking to us for guidance, disinterested guidance, at once honest and fearless. . . .

RULE OF JUSTICE FOR TARIFF AND TRUSTS

What is there to do? It is hard to sum the great task up, but apparently this is the sum of the matter: There are two great things to do. One is to set up the rule of justice and of right in such matters as the tariff, the regulation of the trusts,[2] and the prevention of monopoly, the adaptation of our banking and currency laws to the various uses to which our people must put them, the treatment of those who do the daily labor in our factories and mines and throughout all our great industrial and commercial undertakings, and the political life of the people of the Philippines, for whom we hold governmental power in trust, for their service, not our own. The other, the additional duty, is the great task of protecting our people and our resources and of keeping open to the whole people the doors of opportunity through which they must, generation by generation, pass if they are to make conquest of their fortunes in health, in freedom, in peace, and in contentment. In the performance of this second great duty we are face to face with questions of conservation and of development, questions of forests and water powers and mines and waterways, of the building of an adequate merchant marine, and the opening of every highway and facility and the setting up of every safeguard needed by a great, industrious, expanding nation.

These are all great matters upon which everybody should be heard. We have got into trouble in recent years chiefly because these large things, which ought to have been handled by taking counsel with as large a number of persons as possible, because they touched every interest and the life of every class and region, have in fact been too often handled in private conference. They have been settled by very small, and often deliberately exclusive, groups of men who undertook to speak for the whole Nation, or rather for themselves in the terms of the whole Nation—very honestly it may be true, but very ignorantly sometimes, and very shortsightedly, too—a poor substitute for genuine common counsel. No group of directors, economic or political, can speak for a people. They have neither the point of view nor the knowledge. Our difficulty is not that wicked and designing men have plotted against us, but that our common affairs have been determined upon too narrow a view, and by too private an initiative. Our task now is to effect a great readjustment and get the forces of the whole people once more into play. We need no revolution; we need no excited change; we need only a new point of view and a new method and spirit of counsel.

NATION HAS BEEN AT WAR WITH ITSELF

We are servants of the people, the whole people. The Nation has been unnecessarily, unreasonably, at war within itself. Interest has clashed with interest when there were common principles of right and of fair dealing which might and should have bound them all together, not as rivals, but as partners. As the servants of all, we are bound to undertake the great duty of accommodation and adjustment.

We cannot undertake it except in a spirit which some find it hard to understand. Some people only smile when you speak of yourself as a servant of the people; it seems to them like affectation or mere demagoguery. They ask what the unthinking crowd knows or comprehends of great complicated matters of government. They shrug their shoulders and lift their eyebrows when you speak as if you really believed in presidential primaries, in the direct election of United States Senators, and in an utter publicity about everything that concerns government, from the sources of campaign funds to the intimate debate of the higher affairs of State.

They do not, or will not, comprehend the solemn thing that is in your thought. You know as well as they do that there are all sorts and conditions of men—the unthinking mixed with the wise, the reckless with the prudent, the unscrupulous with the fair and honest—and you know what they sometimes forget, that every class without exception affords a sample of the mixture, the learned and the fortunate no less than the uneducated and the struggling mass. But you see more than they do. You see that these multitudes of men, mixed, of every kind and quality, constitute somehow an organic and noble whole, a single people, and that they have interests which no man can privately determine without their knowledge and counsel. That is the meaning of representative government itself. Representative government is nothing more or less than an effort to give voice to this great body through spokesmen chosen out of every grade and class.

TARIFF HAS BEEN POLITICS INSTEAD OF BUSINESS

You may think that I am wandering off into a general disquisition that has little to do with the business in hand, but I am not. This is business—business of the deepest sort. It will solve our difficulties if you will but take it as business.

See how it makes business out of the tariff question. The tariff question, as dealt with in our time at any rate, has not been business. It has been politics. Tariff schedules have been made up for the purpose of keeping as large a number as possible of the rich and influential manufacturers of the country in a good humor with the Republican Party, which desired their constant financial support. The tariff has become a system of favors, which the phraseology of the schedule was often deliberately contrived to conceal. It becomes a matter of business, of legitimate business, only when the partnership and understanding it represents is between the leaders of Congress and the whole people of the United States, instead of between the leaders of Congress and small groups of manufacturers demanding special recognition and consideration. That is why the general idea of representative government be- comes a necessary part of the tariff question. Who, when you come down to the hard facts of the matter, have been represented in recent years when our tariff schedules were being discussed and determined, not on the floor of Congress, for that is not where they have been determined, but in the committee rooms and conferences? . . .

TARIFF HAS BEEN USED TO FOSTER SPECIAL PRIVILEGE

How does the present tariff look in the light of it? I say nothing for the moment about the policy of protection, conceived and carried out as a disinterested statesman might conceive it. Our own clear conviction as Democrats is, that in the last analysis the only safe and legitimate object of tariff duties, as of taxes of every other kind, is to raise revenue for the support of the Government; but that is not my present point. We denounce the Payne-Aldrich tariff act[3] as the most conspicuous example ever afforded the country of the special favors and monopolistic advantages which the leaders of the Republican Party have so often shown themselves willing to extend to those to whom they looked for campaign contributions. Tariff duties as they have employed them have not been a means of setting up an equitable system of protection. They have been, on the contrary, a method of fostering special privilege. They have made it easy to establish monopoly in our domestic markets. Trusts have owed their origin and their secure power to them. The economic freedom of our people, our prosperity in trade, our untrammeled energy in manufacture depend upon their reconsideration from top to bottom in an entirely different spirit. . . .

DUTIES MUST BE REVISED TO END SPECIAL FAVORS

. . . [Tariff reform] should begin with the schedules which have been most obviously used to kill competition to raise prices in the United States, arbitrarily and without regard to the prices pertaining elsewhere in the markets of the world; and it should, before it is finished or intermitted, be extended to every item in every schedule which affords any opportunity for monopoly, for special advantage to limited groups of beneficiaries, or for subsidized control of any kind in the markets or the enterprises of the country; until special favors of every sort shall have been absolutely withdrawn and every part of our laws of taxation shall have been transformed from a system of governmental patronage into a system of just and reasonable charges which shall fall where they will create the least burden. . . .

There has been no more demoralizing influence in our politics in our time than the influence of tariff legislation, the influence of the idea that the Government was the grand dispenser of favors, the maker and unmaker of fortunes and of opportunities such as certain men have sought in order to control the movement of trade and industry throughout the continent. It has made the Government a prize to be captured and parties the means of effecting the capture. It has made the business men of one of the most virile and enterprising nations of the world timid, fretful, full of alarms; has robbed them of self-confidence and manly force, until they have cried out that they could do nothing without the assistance of the Government at Washington. It has made them feel that their lives depended upon the Ways and Means Committee of the House and the Finance Committee of the Senate (in these later years particularly the Finance Committee of the Senate). They have insisted very anxiously that these committees should be made up only of their "friends"; until the country in its turn grew suspicious and wondered how those committees were being guided and controlled, by what influences and plans of personal advantage. Government cannot be wholesomely conducted in such an atmosphere. Its very honesty is in jeopardy. Favors are never conceived in the general interest; they are always for the benefit of the few, and the few who seek and obtain them have only themselves to blame if presently they seem to be contemned and distrusted.

MAJORITY POORER, THOUGH WAGES HAVE INCREASED

For what has the result been? Prosperity? Yes, if by prosperity you mean vast wealth no matter how distributed, or whether distributed at all, or not; if you mean vast enterprises built up to be presently concentrated under the control of comparatively small bodies of men, who can determine almost at pleasure whether there shall be competition or not. The Nation as a nation has grown immensely rich. . . . But what of the other side of the picture? It is not as easy for us to live as it used to be. Our money will not buy as much. High wages, even when we can get them, yield us no great comfort. We used to be better off with less because a dollar could buy so much more. The majority of us have been disturbed to find ourselves growing poorer, even though our earnings were slowly increasing. Prices climb faster than we can push our earnings up. . . .

LEGISLATION THAT HAS BEEN MADE FOR THE FEW

We naturally ask ourselves, How did these gentlemen get control of these things? Who handed our economic laws over to them for legislative and contractual alteration? . . . Men of the same interest have drawn together, have united their enterprises and have formed trusts; and trusts can control prices. Up to a certain point (and only up to a certain point) great combinations effect great economies in administration, and increase efficiency by simplifying and perfecting organization; but whether they effect economies or not, they can very easily determine prices by intimate agreement so soon as they come to control a sufficient percentage of the product in any great line of business; and we know that they do.

I am not drawing up an indictment against anybody. That is the natural history of such tariffs as are now contrived, as it is the natural history of all other governmental favors and of all licenses to use the Government to help certain groups of individuals along in life. Nobody in particular, I suppose, is to blame, and I am not interested just now in blaming anybody. I am simply trying to point out what the situation is, in order to suggest what there is for us to do if we would serve the country as a whole. The fact is that the trusts have been formed, have gained all but complete control of the larger enterprises of the country, have fixed prices and fixed them high so that profits might be rolled up that were thoroughly worth while, and that the tariff, with its artificial protection and stimulations, gave them the opportunity to do these things and has safeguarded them in that opportunity.

PERIOD OF INFANT INDUSTRIES HAS PASSED

The trusts do not belong to the period of infant industries. They are not the products of the time, that old, laborious time, when the great continent we live on was undeveloped, the young Nation struggling to find itself and get upon its feet amidst older and more experienced competitors. They belong to a very recent and very sophisticated age, when men knew what they wanted and knew how to get it by the favor of the Government. It is another chapter in the natural history of power and of "governing classes." The next chapter will set us free again. There will be no flavor of tragedy in it. It will be a chapter of readjustment, not of pain and rough disturbance. It will witness a turning back from what is abnormal to what is normal. It will see a restoration of the laws of trade, which are the laws of competition and of unhampered opportunity, under which men of every sort are set free and encouraged to enrich the Nation.

I am not one of those who think that competition can be established by law against the drift of a world-wide economic tendency; neither am I one of those who believe that business done upon a great scale by a single organization call it corporation, or what you will is necessarily dangerous to the liberties, even the economic liberties, of a great people like our own, full of intelligence and of indomitable energy. I am not afraid of anything that is normal. I dare say we shall never return to the old order of individual competition, and that the organization of business upon a great scale of cooperation is, up to a certain point, itself normal and inevitable.

BIG BUSINESS NOT DANGEROUS BECAUSE IT IS BIG

Power in the hands of great business men does not make me apprehensive, unless it springs out of advantages which they have not created for themselves. Big business is not dangerous because it is big, but because its bigness is an unwholesome inflation created by privileges and exemptions which it ought not to enjoy. While competition cannot be created by statutory enactment, it can in large measure be revived by changing the laws and forbidding the practices that killed it, and by enacting laws that will give it heart and occasion again. We can arrest and prevent monopoly. It has assumed new shapes and adopted new processes in our time, but these are now being disclosed and can be dealt with.

The general terms of the present Federal antitrust law, forbidding "combinations in restraint of trade," have apparently proved ineffectual. Trusts have grown up under its ban very luxuriantly and have pursued the methods by which so many of them have established virtual monopolies without serious let or hindrance. It has roared against them like any sucking dove. I am not assessing the responsibility. I am merely stating the fact. But the means and methods by which trusts have established monopolies have now become known. It will be necessary to supplement the present law with such laws, both civil and criminal, as will effectually punish and prevent those methods, adding such other laws as may be necessary to provide suitable and adequate judicial processes, whether civil or criminal, to disclose them and follow them to final verdict and judgment. They must be specifically and directly met by law as they develop.

VAST CONFEDERACIES OF BANKS AND RAILWAYS

But the problem and the difficulty are much greater than that. There are not merely great trusts and combinations which are to be controlled and deprived of their power to create monopolies and destroy rivals; there is something bigger still than they are and more subtle, more evasive, more difficult to deal with. There are vast confederacies (as I may perhaps call them for the sake of convenience) of banks, railways, express companies, insurance companies, manufacturing corporations, mining corporations, power and development companies, and all the rest of the circle, bound together by the fact that the ownership of their stock and the members of their boards of directors are controlled and determined by comparatively small and closely interrelated groups of persons who, by their informal confederacy, may control, if they please and when they will, both credit and enterprise. There is nothing illegal about these confederacies, so far as I can perceive. They have come about very naturally, generally without plan or deliberation, rather because there was so much money to be invested, and it was in the hands, at great financial centers, of men acquainted with one another and intimately associated in business, than because any one had conceived and was carrying out a plan of general control; but they are none the less potent a force in our economic and financial system on that account. They are part of our problem. Their very existence gives rise to the suspicion of a "money trust," a concentration of the control of credit which may at any time become infinitely dangerous to free enterprise. If such a concentration and control does not actually exist it is evident that it can easily be set up and used at will. Laws must be devised which will prevent this, if laws can be worked out by fair and free counsel that will accomplish that result without destroying or seriously embarrassing any sound or legitimate business undertaking or necessary and wholesome arrangement.

Let me say again that what we are seeking is not destruction of any kind nor the disruption of any sound or honest thing, but merely the rule of right and of the common advantage. I am happy to say that a new spirit has begun to show itself in the last year or two among influential men of business, and, what is perhaps even more significant, among the lawyers who are their expert advisers; and that this spirit has displayed itself very notably in the last few months in an effort to return, in some degree at any rate, to the practices of genuine competition. Only a very little while ago our men of business were united in resisting every proposal of change and reform as an attack on business, an embarrassment to all large enterprise, an intimation that settled ideas of property were to be set aside and a new and strange order of things created out of hand. . . .

BIG BUSINESS MEN ARE SEEING THE LIGHT

It is a happy omen that their attitude has changed. They see that what is right can hurt no man; that a new adjustment of interests is inevitable and desirable, is in the interest of everybody; that their own honor, their own intelligence, their own practical comprehension of affairs is involved. They are beginning to adjust their business to the new standards. Their hand is no longer against the Nation; they are part of it; their interests are bound up with its interests. This is not true of all of them; but it is true of enough of them to show what the new age is to be and how the anxieties of statesmen are to be eased if the light that is dawning broadens into day.

If I am right about this, it is going to be easier to act in accordance with the rule of right and justice in dealing with the labor question. The so-called labor question is a question only because we have not yet found the rule of right in adjusting the interests of labor and capital. The welfare, the happiness, the energy and spirit of the men and women who do the daily work in our mines and factories, on our railroads, in our offices and marts of trade, on our farms and on the sea, are of the essence of our national life. There can be nothing wholesome unless their life is wholesome; there can be no contentment unless they are contented. Their physical welfare affects the soundness of the whole Nation. We shall never get very far in the settlement of these vital matters so long as we regard everything done for the workingman, by law or by private agreement, as a concession yielded to keep him from agitation and a disturbance of our peace. Here, again, the sense of universal partnership must come into play if we are to act like statesmen, as those who serve, not a class, but a nation.

FIRST REGARD MUST BE CARE OF WORKING PEOPLE

The working people of America—if they must be distinguished from the minority that constitutes the rest of it—are, of course, the backbone of the Nation. No law that safeguards their life, that makes their hours of labor rational and tolerable, that gives them freedom to act in their own interest, and that protects them where they cannot protect themselves, can properly be regarded as class legislation or as anything but as a measure taken in the interest of the whole people, whose partnership in right action we are trying to establish and make real and practical. . . .

. . . [I]n dealing with the complicated and difficult question of the reform of our banking and currency laws it is plain that we ought to consult very many persons besides the bankers, not because we distrust the bankers, but because they do not necessarily comprehend the business of the country, notwithstanding they are indispensable servants of it and may do a vast deal to make it hard or easy. No mere bankers' plan will meet the requirements, no matter how honestly conceived. It should be a merchants' and farmers' plan as well, elastic in the hands of those who use it as an indispensable part of their daily business. . . .

WE MERELY HOLD THE PHILIPPINES IN TRUST

In dealing with the Philippines we should not allow ourselves to stand upon any mere point of pride, as if, in order to keep countenance in the families of nations, it were necessary for us to make the same blunders of selfishness that other nations have made. We are not the owners of the Philippine Islands. We hold them in trust for the people who live in them. They are theirs, for the uses of their life. We are not even their partners. It is our duty, as trustees, to make whatever arrangement of government will be most serviceable to their freedom and development. Here, again, we are to set up the rule of justice and of right.

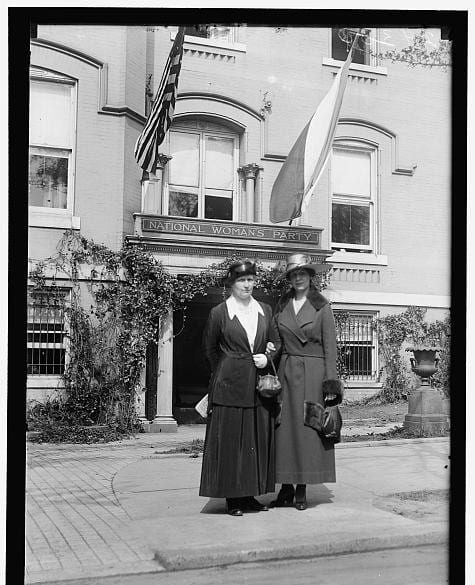

The rule of the people is no idle phrase; those who believe in it—as who does not that has caught the real spirit of America?—believe that there can be no rule of right without it; that right in politics is made up of the interests of everybody, and everybody should take part in the action that is to determine it. We have been keen for presidential primaries and the direct election of United States Senators, because we wanted the action of the Government to be determined by persons whom the people had actually designated as men whom they were ready to trust and follow. We have been anxious that all campaign contributions and expenditures should be disclosed to the public in fullest detail, because we regarded the influences which govern campaigns to be as much a part of the people's business as anything else connected with their Government. We are working toward a very definite object the universal partnership in public affairs upon which the purity of politics and its aim and spirit depend. . . .

WE MUST HUSBAND OUR NATURAL RESOURCES

I do not know any greater question than that of conservation. We have been a spendthrift nation, and now must husband what we have left. We must do more than that. We must develop, as well as preserve, our water powers and must add great waterways to the transportation facilities of the nation, to supplement the railways within our borders as well as upon the Isthmus. We must revive our merchant marine, too, and fill the seas again with our own fleets. We must add to our present post-office service a parcel post as complete as that of any other nation. We must look to the health of our people upon every hand, as well as hearten them with justice and opportunity. This is the constructive work of government. This is the policy that has a vision and a hope and that looks to serve mankind. . . .

With regard to the development of greater and more numerous waterways and the building up of a merchant marine, we must follow great constructive lines and not fall back upon the cheap device of bounties and subsidies. In the case of the Mississippi River, that great central artery of our trade, it is plain that the Federal Government must build and maintain the levees and keep the great waters in harness for the general use. It is plain, too, that vast sums of money must be spent to develop new waterways where trade will be most served and transportation most readily cheapened by them. Such expenditures are no largess on the part of the Government; they are national investments.

AMERICAN SHIPS MUST CARRY AMERICAN GOODS

The question of a merchant marine turns back to the tariff again, to which all roads seem to lead, and to our registry laws, which, if coupled with the tariff, might almost be supposed to have been intended to take the American flag off the seas. Bounties are not necessary, if you will but undo some of the things that have been done. Without a great merchant marine we cannot take our rightful place in the commerce of the world. Merchants who must depend upon the carriers of rival mercantile nations to carry their goods to market are at a disadvantage in international trade too manifest to need to be pointed out; and our merchants will not long suffer themselves ought not to suffer themselves to be placed at such a disadvantage. Our industries have expanded to such a point that they will burst their jackets if they cannot find a free outlet to the markets of the world; and they cannot find such an outlet unless they be given ships of their own to carry their goods ships that will go the routes they want them to go and prefer the interests of America in their sailing orders and their equipment. Our domestic markets no longer suffice. We need foreign markets. That is another force that is going to break the tariff down. The tariff was once a bulwark; now it is a dam. For trade is reciprocal; we cannot sell unless we also buy.

The very fact that we have at last taken the Panama Canal seriously in hand and are vigorously pushing it toward completion is eloquent of our reawakened interest in international trade. We are not building the canal and pouring out millions upon millions of money upon its construction merely to establish a water connection between the two coasts of the continent, important and desirable as that may be, particularly from the point of view of naval defense. It is meant to be a great international highway. It would be a little ridiculous if we should build it and then have no ships to send through it. . . .

EDUCATION IS A PART OF CONSERVATION

There is another duty which the Democratic Party has shown itself great enough and close enough to the people to perceive, the duty of Government to share in promoting agricultural, industrial, vocational education in every way possible within its constitutional powers. No other platform has given this intimate vision of a party's duty. The Nation cannot enjoy its deserved supremacy in the markets and enterprises of the world unless its people are given the ease and effectiveness that come only with knowledge and training. Education is part of the great task of conservation, part of the task of renewal and of perfected power.

We have set ourselves a great program, and it will be a great party that carries it out. It must be a party without entangling alliances with any special interest whatever. It must have the spirit and the point of view of the new age. Men are turning away from the Republican Party, as organized under its old leaders, because they found that it was not free; that it was entangled; and they are turning to us because they deem us free to serve them. They are immensely interested, as we are, as every man who reads the signs of the time and feels the spirit of the new age is, in the new program. . . .

IT IS A CONTEST OF PRINCIPLES

A presidential campaign may easily degenerate into a mere personal contest and so lose its real dignity and significance. There is no indispensable man. The Government will not collapse and go to pieces if any one of the gentlemen who are seeking to be entrusted with its guidance should be left at home. But men are instruments. We are as important as the cause we represent, and in order to be important must really represent a cause. What is our cause? The people's cause. That is easy to say, but what does it mean? The common as against any particular interest whatever? Yes, but that, too, needs translation into acts and policies. We represent the desire to set up an unentangled government, a government that cannot be used for private purposes, either in the field of business or in the field of politics; a government that will not tolerate the use of the organization of a great party to serve the personal aims and ambitions of any individual, and that will not permit legislation to be employed to further any private interest. It is a great conception, but I am free to serve it, as you also are. I could not have accepted a nomination which left me bound to any man or group of men. . . .

To be free is not necessarily to be wise. But wisdom comes with counsel, with the frank and free conference of untrammeled men united in the common interest. Should I be entrusted with the great office of President, I would seek counsel wherever it could be had upon free terms. I know the temper of the great convention which nominated me; I know the temper of the country that lay back of that convention and spoke through it. I heed with deep thankfulness the message you bring me from it. I feel that I am surrounded by men whose principles and ambitions are those of true servants of the people. I thank God, and will take courage.

- 1. Ollie M. James (1871–1918), a Representative and later Senator from Kentucky was the chairman of the Convention.

- 2. “Trust” referred to control by one or more people over a number of firms operating in the same area of the economy, for example steel production or the railroads. A “Trust,” sometimes referred to as a “combination,” came about when shareholders in different corporations transferred their shares to one corporate entity that held them (hence, a “holding company”). The holding company or Trust could be used to establish a monopoly over an area of the economy, for example steel production or the railroads. A “Trust,” sometimes referred to as a “combination,” came about when shareholders in different corporations transferred their shares to one corporate entity that held them (hence, a “holding company”). The holding company or Trust could be used to establish a monopoly over an area of the economy. For this reason, “trust busting” became part of the U.S. government’s effort to insure free markets in the United States.

- 3. Passed with the support of President Taft, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 was intended to lower tariff rates, but not to the degree that progressives demanded. The tariff issue helped to split the Republican Party into its progressive and conservative wings in 1912, with many on the conservative wing arguing for high protective tariffs and progressives arguing for lower tariff rates. Rates were lowered from 40% to 26% in the Wilson administration by the Underwood Tariff Act of 1913.

Campaign Address in Scranton, Penn.

September 23, 1912

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.