The Election of 1912: John Moser's new Reacting to the Past Game

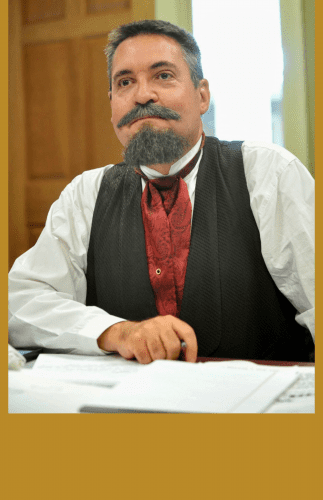

Professor John Moser is well known in the MAHG program for using carefully designed role-playing games to teach historical events and periods. Moser has co-authored a number of gamebooks in the Reacting to the Past (RTTP) series. These games begin in a pivotal moment of history, when citizen groups contest for power or face critical decisions. Each player assumes the identity of one historical actor, taking on this person’s motives, core beliefs and goals. The game unfolds as players declare their positions and appeal for others’ support.

This summer, Professor Moser will teach the “Progressive Era” course using a Reacting to the Past game he is currently developing with the help of another history professor at Samford University. We asked him how the game will illuminate the Progressive era.

You call this game Progressivism at High Tide, since it takes place during the only presidential election in US history when all of the candidates called themselves progressives. Yet the “historical background” in the gamebook discusses a diversity of progressive views. How do you define Progressivism?

The difficulty of defining progressivism in practice actually inspired this game. I’d been reading Sid Milkis’s book, Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party and the Transformation of American Democracy, and realizing that it’s one thing to talk about progressive ideas in theory and another to talk about transforming those ideas into a political agenda.

The Cold War historian John Lewis Gaddis divides scholars into “Lumpers” and “Splitters.” Lumpers point to commonalities; Splitters draw distinctions. From my perspective, the political theorists who have taught the Progressive Era in MAHG are very much lumpers. They ask, what do thinkers as different as Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Jane Addams believe in common? They answer: All these thinkers say that the republic established by the founders was designed for the conditions prevailing in the late 18th century. Now it must be revised to face the challenges of the modern world.

That’s a valid observation. But it glosses over some really huge differences. As a historian, I look at particular individuals, what they believed and did. The measures they proposed responded to galvanizing events. You should not be able to take the AHG 505 Progressive Era course without ever hearing mention of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire!

The question of big business divided the Progressive Party. Some, like Theodore Roosevelt, saw the trusts as an inevitable feature of the modern economy. They would allow the trusts to develop but regulate them in the public interest. Yet many of those who followed Roosevelt out of the Republican party in 1912 were dismayed by this language in the new Progressive Party platform. They agreed with President Taft, who saw US Steel violating the Sherman Antitrust Act and said, “the law is the law!”

Who was the real progressive? Taft, who thought US Steel a combination in restraint of trade and tried to break it up? Or Roosevelt, who would use the Sherman Antitrust Act strictly as a bludgeon, forcing those who act against the public interest to change?

Progressives disagreed on many other things. Some argued for civil rights laws or women’s suffrage; others opposed these reforms. Some supported labor unions and resented mandatory government mediation during strikes; others would improve labor conditions through government regulation.

I don’t see progressivism as one monolithic movement. But the differences between progressive factions can make you wonder if progressivism is even a meaningful term. This diversity leaves room for certain historians to define all the things that we like as progressive, and those we deplore as non-progressive. The truth is, some progressives pushed segregation and the disenfranchisement of blacks on what they saw as progressive grounds. They favored excluding the illiterate or ill-educated from the franchise. Prohibition is another instance. Some opposed it, but many favored it.

The progressive label is still used. How would you define progressivism today?

We say the Progressive Era ended around 1920, but by then they had fundamentally changed things. Still, certain social elements of what we call Progressivism today—the importance of personal liberation—only became important in the 1960s and 1970s.

In our last class sessions, after the game ends, we’ll discuss readings from recent history. In many ways, today’s progressives would look back on the progressives of the early 20th century and recoil. Early Progressives spoke of the need to move away from rights, toward duties; away from the interests of the individual toward those of the community. Today, much of the progressive social agenda supports the right of individuals to do pretty much as they please. Contrast that with Theodore Roosevelt. He comes out for women’s suffrage in an article that reminds women of their duty to bear and raise children.

For this game, have you selected many of the same documents you would use in previous seminars on the Progressive era?

The core texts we use are all ones used in the past: Roosevelt’s “New Nationalism” speech, Wilson’s “Authors and Signers of the Declaration of Independence.” These get to the question of what progressivism is. I added Eugene V. Debs’ acceptance speech, because Debs is a character in the game, and everyone needs to understand that for Debs, socialism is a form of progressivism.

The supplemental documents take up particular issues. All the characters in the game who are not candidates for president are advocating policies on particular issues. For example, the student who plays George Perkins (an ally of Teddy Roosevelt who was a partner at J. P. Morgan and on the board of US Steel) will rely on Perkins’ speech “The Modern Corporation.” The person playing Victor Berger, the first socialist elected to the US Congress, will be able to read Berger’s piece arguing trusts should be nationalized. The readings cover eight issues: direct democracy (should measures like primaries, recall elections, and ballot initiatives be instituted?); big business; immigration; women’s suffrage, racial equality; labor reforms; the tariff; and organized labor.

Each player makes a speech advocating a position on one of these issues. Hence, different players will specialize in different issues and in effect teach them to the rest of the class. Everyone will read every reading, but those focused on a problem will have to know the related reading really solidly.

What other overall lessons does this way of studying history teach?

It helps you understand the calculations politicians and activists must make. No one begins this game as the member of a faction. But players will be listening for presidential candidates to support their particular issues. They’ll endorse candidates who do. Then they are on those candidates’ teams, working to get them elected.

Take the example of racial equality. A candidate who thinks W. E. B. Dubois’s endorsement is important might come out in favor of enforcing voting rights in the South, desegregating the schools, or passing an anti-lynching law. But if the candidate thinks the support of white Southerners is more important, he will not make statements in favor of civil rights. This was a dilemma for Teddy Roosevelt—and for W. E. B. Du Bois, who heard no one supporting his issues. In the game, Du Bois must decide which candidate is least objectionable—or whether to endorse no one at all.

Certainly the game teaches the value of teamwork. This game in particular also emphasizes civility. As American elections go, this was a fairly tame one. The speeches in the course of the game will be more like Chautauquas, with speakers talking about what is near and dear to their hearts.

The game concludes in the election of 1912. Might the candidate who won in history lose in the game?

It’s almost guaranteed the Democrat’s going to win the election. But that person will not necessarily be Wilson. When the game begins, the Republican Party has already split and Taft and Debs have already gotten their parties’ nominations. The first session covers both the Progressive Party and the Democratic Party conventions. Historically, the candidate favored to get the Democratic nomination was Champ Clark of Missouri. He had a majority on the first ballot, but not the 2/3 majority the party required. So there will be a lot of negotiation during the Democratic Party convention.

I’ve built into the game victory conditions so that Taft, Roosevelt and certainly Debs don’t have to be elected president in order to win the game; they just have to do better than they did historically. If Eugene V. Debs gets any electoral votes at all he wins the game, because historically, Debs’ 200,000 votes gave him no votes in the electoral college. Conversely, Wilson doesn’t win the game just by being elected; he needs to win by a wider margin than was historically the case.

I’ve always found students compete to win. While some professors using RTTP games award a small number of points toward the final grade to the students on the winning team, I’ve never felt I had to do that.

Since you’ve begun using RTTP in the MAHG program, have you heard of teachers using or adapting the games to their classrooms at home?

I know that that there are certain teachers who now use the games, and others who adapt portions of them. They might design a lesson in which teams debate a particular issue, or in which students write editorials advocating a position on an issue of the era.

Every time I use RTTP, teachers ask me, “How do I use this in my class?” I have to be a little careful, because the RTTP consortium does not officially recommend use of the game in high schools. They don’t discourage it either, but they have a very small staff who lack the time to answer teacher questions. When teachers tell me they plan to use a game, I give them pointers if they want them and say that they can contact me later.