Introduction

Until the last decades of the twentieth century, the federal government spoke of its policy toward Native Americans in one of two ways, either solving the “Indian problem” or getting itself out of the “Indian business.” Every change in policy from Removal in the 1830s (See Petitions of Cherokee Women, Letter to John C. Calhoun, Address at Inter-Tribal Council at Tahlequah) to Termination and Relocation (See House Concurrent Resolution 108 and Reaffirmed Statement on Indian Policy) and the Indian Claims Commission, established by the Indians Claim Act (1946; see Legal Status of Indians), were thought of in these terms.

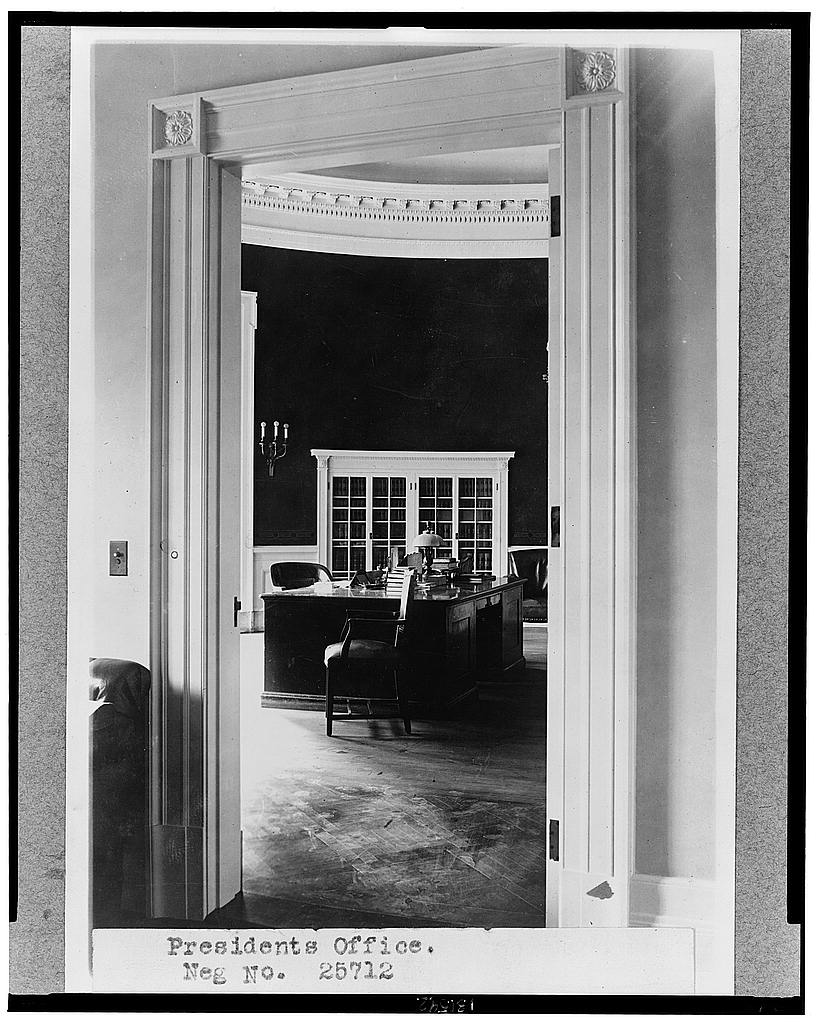

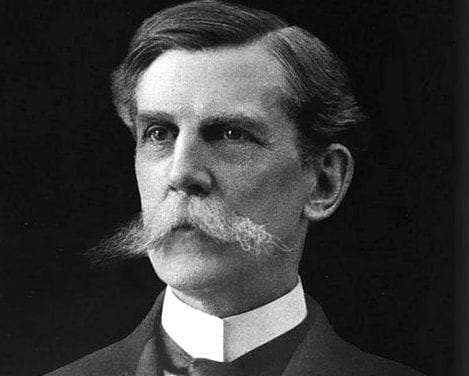

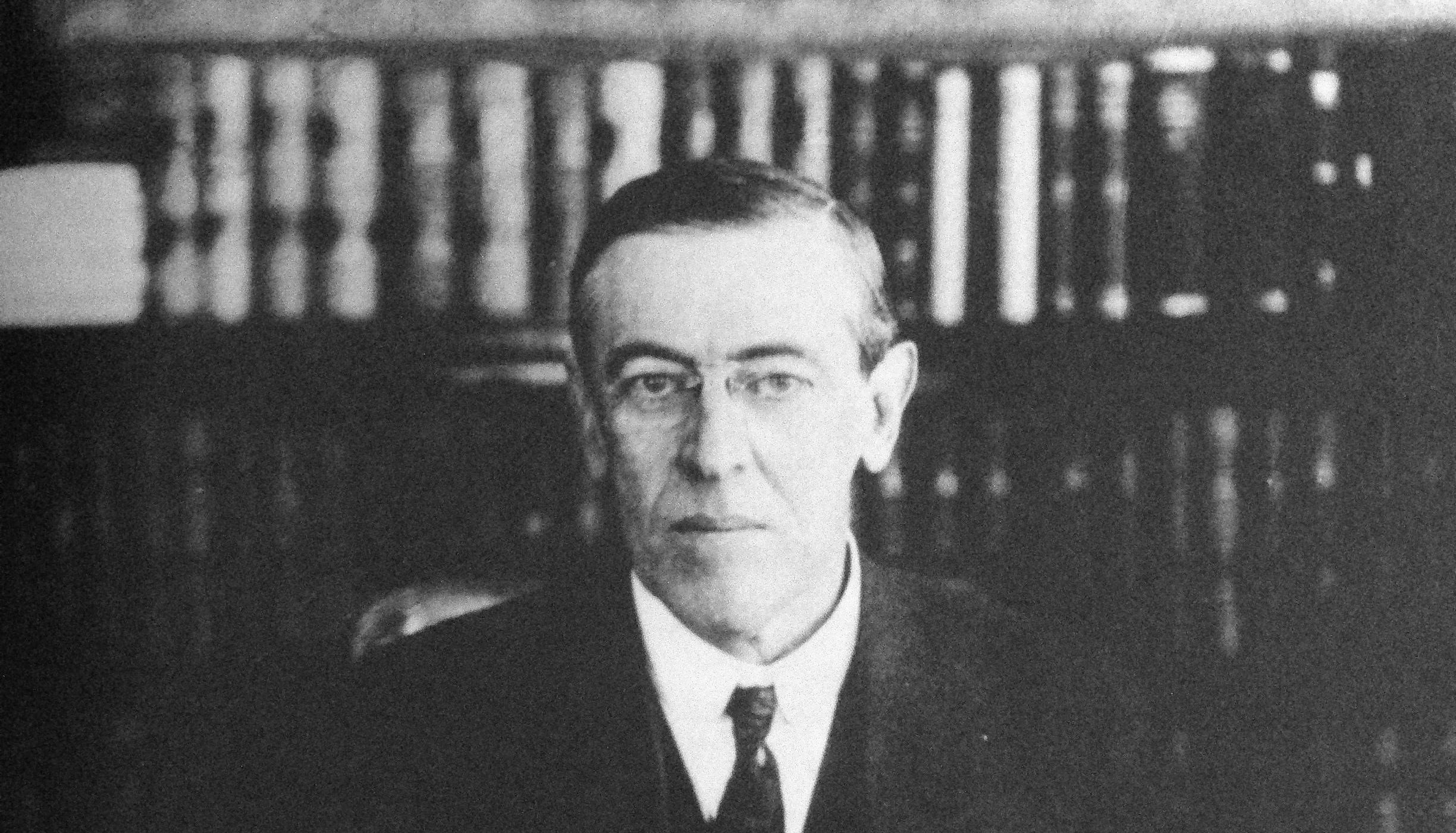

Ruth Muskrat Bronson (1897–1982) was a noted Cherokee poet, educator, and outspoken activist for Indian rights. In 1923 she met President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. In this excerpt from the speech she delivered on that occasion, she explained how she thought Indians understood the “Indian problem.”

This source came to light when a descendent of the author brought it to an antique show.

—Jace Weaver

. . . Mr. President, there have been so many discussions of the so-called Indian problem. May not we, who are the Indian students of America, who must face the burden of that problem, say to you what it means to us? You know that in the old days there were mighty Indian leaders—men of vision, of courage, and of exalted ideals. History tells us first of Chief Powhatan who met a strange people on the shores of his country and welcomed them as brothers; Massasoit, who offered friendship and shared his kingdom. Then appeared another type of leader, the war chief, fighting to defend his home and his people. The members of my race will never forget the names of King Philip, of Chief Joseph, of Tecumseh.1 To us they will always be revered as great leaders who had the courage to fight, “campaigning for their honor, a martyr to the soil of their fathers.”2 Cornstalk, the great crater, Red Jacket of the Senacas [sic], and Sequoyah of the Cherokees were other noted leaders of our race who have meant much in the development of my people.3 It was not accidental that these ancient leaders were great. There was some hidden energy, some great driving inner ambition, some keen penetration of vision and high idealism that urged them on.

What made the older leaders great still lives in the hearts of the Indian youth of today. The same potential greatness lies deep in the souls of the Indian students of today who must become the leaders of this new era. The old life has gone. A new trail must be found, for the old is not good to travel farther. We are glad to have it so. But these younger leaders who must guide their people along new and untried paths have perhaps a harder task before them than the fight for freedom our older leaders made. Ours must be the problem of leading this vigorous and by no means dying race of people back to their rightful heritage of nobility and greatness. Ours must be the task of leading through these difficult stages of transition into economic independence, into a more adequate expression of their art, and into an awakened spiritual vigor. Ours is a vision as keen and as penetrating as any vision of old. We want to understand and to accept the civilization of the white man. We want to become citizens of the United States, and to have our share in the building of this great nation, that we love. But we want also to preserve the best that is in our own civilization. We want to make our own unique contribution to the civilizations of the world—to bring our own peculiar gifts to the altar of that great spiritual and artistic unity which such a nation as America must have. This, Mr. President, is the Indian problem which we who are Indians find ourselves facing. No one can find our solution for us but ourselves.

In order to find a solution we must have schools; we must have encouragement and help from our white brothers. Already there are schools, but the number is pitifully inadequate. And already the beginnings toward an intelligent and sympathetic understanding of our needs and our longing have been made through such efforts as this book represents. For these today, as never before, the trail ahead for the Indian looks clear and bright with promise. But it is yet many long weary miles until the end. . . .