No related resources

Introduction

In 1826 the Cherokee Nation sent Elias Boudinot (1802–1839) and his cousin John Ridge (1802–1839), two highly educated Cherokees, on a speaking tour of cities in the eastern United States. The stated purpose was to raise money to buy a printing press (and type) and to establish a college. An unstated objective, however, was to arouse the sympathies of northerners in favor of the Cherokees’ struggles to avoid removal and remain on their homelands.

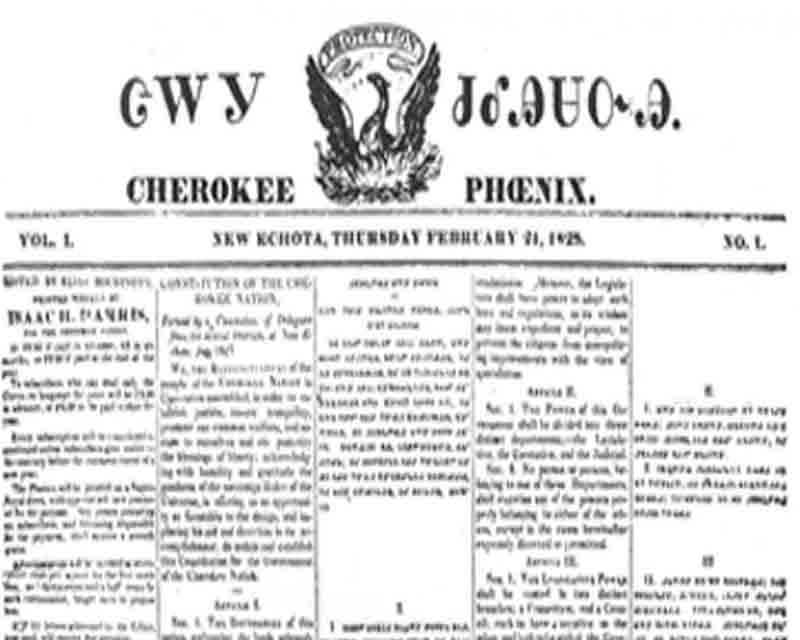

The tour was successful. The Cherokee Nation started the Cherokee Phoenix, the country’s first tribal newspaper, published in both English and Cherokee and edited by Boudinot. Due to the ongoing removal crisis, however, the academy was not built. Finally, in 1851, in its new homeland (present-day Oklahoma), the Cherokee Nation opened not one but two colleges, one for men and one for women. The Cherokee National Female Seminary was the first institution of higher education for women west of the Mississippi River.

The speech Boudinot delivered in Philadelphia was written down and published in a short book, which became a bestseller. An edited version of that talk appears here.

Boudinot and Ridge believed that the Cherokee should assimilate in order to survive. They later also supported removal and signed a treaty (the Treaty of Echota, 1835) with the U.S. government. After they relocated to what is now Oklahoma, both Boudinot and Ridge were assassinated by opponents of the removal.

Elias Boudinot, An Address to the Whites: Delivered in the First Presbyterian Church, on the 26th of May, 1826, https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:427890/asc:428168.

To those who are unacquainted with the manners, habits, and improvements of the aborigines of this country, the term “Indian” is pregnant with ideas the most repelling and degrading. But such impressions—originating as they frequently do from infant prejudices, although they hold too true when applied to some—do great injustice to many of this race of beings.

Some there are, perhaps even in this enlightened assembly, who at the bare sight of an Indian or at the mention of the name, would throw back their imaginations to ancient times, to the ravages of savage warfare, to the yells pronounced over the mangled bodies of women and children, thus creating an opinion, inapplicable and highly injurious to those for whose temporal interest and eternal welfare, I come to plead.

What is an Indian? Is he not formed of the same materials with yourself? For “of one blood God created all the nations that dwell on the face of the earth.”1 Though it be true that he is ignorant, that he is a heathen, that he is a savage, yet he is no more than all others have been under similar circumstances. Eighteen centuries ago what were the inhabitants of Great Britain?

You here behold an Indian, my kindred are Indians, and my fathers sleeping in the wilderness grave—they too were Indians. But I am not as my fathers were—broader means and nobler influences have fallen on me.2 Yet I was not born as thousands are, in a stately dome and amid the congratulations of the great, for on a little hill, in a lonely cabin, overspread by the forest oak, I first drew my breath; and in a language unknown to learned and polished nations, I learnt to lisp my fond mother’s name. In after days, I have had greater advantages than most of my race; and I now stand before you delegated by my native country to seek her interest, to labor for her respectability, and by my public efforts to assist in raising her to an equal standing with other nations of the earth.

The time has arrived when speculations and conjectures as the practicability of civilizing the Indians must forever cease. A period is fast approaching when the stale remark—“Do what you will, an Indian will still be an Indian”—must be placed no more in speech. With whatever plausibility this popular objection may have heretofore been made, every candid mind must now be sensible that it can no longer be uttered, except by those who are uninformed with respect to us, who are strongly prejudiced against us, or who are filled with vindictive feelings toward us; for the present history of the Indians, particularly of that nation to which I belong, most incontrovertibly establishes the fallacy of this remark. I am aware of the difficulties which have ever existed to Indian civilization. I do not deny the almost insurmountable obstacles which we ourselves have thrown in the way of this improvement, nor do I say that difficulties no longer remain; but facts will permit me to declare that there are none which may not easily be overcome by strong and continued exertions. It needs not abstract reasoning to prove this position. It needs not the display of language to prove to the minds of good men, that Indians are susceptible of attainments necessary to the formation of polished society. It needs not the power of argument on the nature of man to silence forever the remark that “it is the purpose of the Almighty that the Indians should be exterminated.” It needs only that the world should know what we have done in the last few years, to foresee what yet we may do with the assistance of our white brethren and that of the common Parent of us all.

It is not necessary to present to you a detailed account of the various aboriginal tribes who have been known to you only on the pages of history, and there but obscurely known. They have gone; and to revert back to their days would be only to disturb their oblivious sleep; to darken these walls with deeds at which humanity must shudder; to place before your eyes the scenes of Muskingum Sahta-goo and the plains of Mexico; to call up the crimes of the bloody Cortes and his infernal host;3 and to describe the animosity and vengeance which have overthrown and hurried into the shades of death those numerous tribes. But here let me say that, however guilty these unhappy nations may have been, yet many and unreasonable were the wrongs they suffered, many the hardships they endured, and many their wanderings through the trackless wilderness. Yes, [as Washington Irving noted]:

Notwithstanding the obloquy with which the early historians of the colonies have overshadowed the character of the ignorant and unfortunate natives, some bright gleams will occasionally break through, that throw a melancholy luster on their memories. Facts are occasionally to be met with in their rude annals, which, though recorded with all the coloring of prejudice and bigotry, yet speak for themselves, and will be dwelt upon with applause and sympathy when prejudice shall have passed away.4

Nor is it my purpose to enter largely into the consideration of the remnants, of those who have fled with time and are no more. They stand as monuments of the Indian’s fate. And should they ever become extinct, they must move off the earth, as did their fathers. My design is to offer a few disconnected facts relative to the present improved state and to the ultimate prospects of that particular tribe called Cherokees to which I belong.

The Cherokee Nation lies within the charted limits of the states of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama. Its extent as defined by treaties is about 200 miles in length from east to west, and about 120 in breadth. This country, which is supposed to contain about 10,000,000 acres, exhibits great varieties of surface, the most part being hilly and mountainous, affording soil of no value. The valleys, however, are well watered and afford excellent land in many parts, particularly on the large streams, that [are] of the first quality. The climate is temperate and healthy. Indeed, I would not be guilty of exaggeration were I to say that the advantages which this country possesses to render it salubrious are many and superior. Those lofty and barren mountains, defying the labor and ingenuity of man and supposed by some as placed there only to exhibit omnipotence, contribute to the healthiness and beauty of the surrounding plains and give to us that free air and pure water which distinguish our country. These advantages, calculated to make the inhabitants healthy, vigorous, and intelligent, cannot fail to cause this country to become interesting. And there can be no doubt that the Cherokee Nation, however obscure and trifling it may now appear, will finally become, if not under its present occupants, one of the garden spots of America. And here, let me be indulged in the fond wish that she may thus become under those who now possess her; and ever be fostered, regulated, and protected by the generous government of the United States.

The population of the Cherokee Nation increased from the year 1810 to that of 1824 [by] 2,000, exclusive of those who emigrated in 1818 and 19 to the west of the Mississippi. Of those who reside on the Arkansas, the number is supposed to be about 5,000.

The rise of these people in their movement toward civilization may be traced as far back as the relinquishment of their towns, when game became incompetent to their support by reason of the surrounding white population. They then betook themselves to the woods, commenced the opening of small clearings and the raising of stock, still however following the chase. Game has since become so scarce that little dependence for subsistence can be placed upon it. They have gradually, and I could almost say universally, forsaken their ancient employment. In fact, there is not a single family in the nation that can be said to subsist on the slender support which the wilderness would afford. The love and the practice of hunting are not now carried to a higher degree than among all frontier people, whether white or red. It cannot be doubted, however, that there are many who commenced a life of agricultural labor from mere necessity, and if they could, would gladly resume their former course of living. But these are individual failings and ought to be passed over.

On the other hand it cannot be doubted that the nation is improving, rapidly improving, in all those particulars which must finally constitute the inhabitants an industrious and intelligent people.

It is a matter of surprise to me, and must be to all those who are properly acquainted with the condition of the Aborigines of this country, that the Cherokees have advanced so far and so rapidly in civilization. But there are yet powerful obstacles, both within and without, to be surmounted in the march of improvement. The prejudices in regard to them in the general community are strong and lasting. The evil effects of their intercourse with their immediate white neighbors, who differ from them chiefly in name, are easily to be seen, and it is evident that from this intercourse proceed those demoralizing practices which in order to surmount, peculiar and unremitting efforts are necessary. In defiance, however, of these obstacles, the Cherokees have improved and are still rapidly improving. . . .

. . .In one district there were, last winter, upward of 1,000 volumes of good books; and 11 different periodical papers both religious and political, which were taken and read. On the public roads there are many decent Inns, and few houses for convenience, etc., would disgrace any country. Most of the schools are under the care and tuition of Christian missionaries, of different denominations, who have been of great service to the nation by inculcating moral and religious principles into the minds of the rising generation. In many places the word of God is regularly preached and explained, both by missionaries and natives; and there are numbers who have publicly professed their belief and interest in the merits of the great Savior of the world. It is worth[y] of remark, that in no ignorant country have the missionaries undergone less trouble and difficulty, in spreading a knowledge of the Bible, than in this. Here, they have been welcomed and encouraged by the proper authorities of the nation, their persons have been protected, and in very few instances have some individual vagabonds threatened violence to them. Indeed it may be said with truth, that among no heathen people has the faithful minister of God experienced greater success, greater reward for his labor, than in this. He is surrounded by attentive hearers, the words which flow from his lips are not spent in vain. The Cherokee have had no established religion of their own, and perhaps to this circumstance we may attribute, in part, the facilities with which missionaries have pursued their ends. They cannot be called idolaters; for they never worshipped images. They believed in a Supreme Being, the Creator of all, the God of the white, the red, and the black man. They also believed in the existence of an evil spirit who resided, as thought, in the setting sun, the future place of all who in their lifetime had done iniquitously. Their prayers were addressed alone to the Supreme Being, and which if written would fill a large volume, and display much sincerity, beauty, and sublimity. When the ancient customs of the Cherokees were in their full force, no warrior thought himself secure, unless he had addressed his guardian angel; no hunter could hope for success, unless before the rising sun he had asked the assistance of his God, and on his return at eve he had offered his sacrifice to him.

There are three things of late occurrence, which must certainly place the Cherokee Nation in a fair light, and act as a powerful argument in favor of Indian improvement.

First. The invention of letters.

Second. The translation of the New Testament into Cherokee.

And third. The organization of a government.

The Cherokee mode of writing lately invented by George Guest,5 who could not read any language nor speak any other than his own, consists of eighty-six characters, principally syllabic, the combinations of which form all the words of the language. Their terms may be greatly simplified, yet they answer all the purpose of writing, and already many natives use them.

The translation of the New Testament, together with Guest’s mode of writing, has swept away that barrier which has long existed, and opened a spacious channel for the instruction of adult Cherokee. Persons of all ages and classes may now read the precepts of the Almighty in their own language. Before it is long, there will scarcely be an individual in the nation who can say, “I know not God neither understand I what thou says,”6 for all shall know him from the greatest to the least. The aged warrior over whom has rolled three score and ten years of savage life will grace the temple of God with his hoary head; and the little child yet on the breast of its pious mother shall learn to lisp its Maker’s name.

The shrill sound of the savage yell shall die away as the roaring of far distant thunder; and the heaven wrought music will gladden the affrighted wilderness. “The solitary places will be glad for them, and the desert shall rejoice and blossom as a rose.”7 Already do we see the morning star, forerunner of approaching dawn, rising over the tops of those deep forests in which for ages have echoed the warrior’s whoop. But has not God said it, and will he not do it? The Almighty decrees his purposes, and man cannot with all his ingenuity and device countervail them. They are more fixed in their course than the rolling sun—more durable than the everlasting mountains.

The [Cherokee] government, though defective in many respects, is well suited to the condition of its inhabitants. As they rise in information and refinement, changes in it must follow, until they arrive at that state of advancement, when I trust they will be admitted into all the privileges of the American family. The Cherokee Nation is divided into eight districts, in each of which are established courts of justice, where all disputed cases are decided by a jury, under the direction of a circuit judge, who has jurisdiction over two districts. Sheriffs and other public officers are appointed to execute the decisions of the courts, collect debts, and arrest thieves and other criminals. Appeals may be taken to the Superior Court, held annually at the seat of government. The legislative authority is vested in a General Court, which consists of the National Committee and Council. The National Committee consists of thirteen members, who are generally men of sound sense and fine talents. The National Council consists of thirty-two members, beside[s] the speaker, who act as the representatives of the people. Every bill passing these two bodies becomes the law of the land. Clerks are appointed to do the writings and record the proceedings of the Council. The executive power is vested in two principal chiefs, who hold their office during good behavior, and sanction all the decisions of the legislative council. Many of the laws display some degree of civilization and establish the respectability of the nation.

Polygamy is abolished. Female chastity and honor are protected by law. The Sabbath is respected by the Council during session. Mechanics are encouraged by law. The practice of putting aged persons to death for witchcraft is abolished and murder has now become a governmental crime. From what I have said, you will form but a faint opinion of the true state and prospects of the Cherokee. You will, however, be convinced of three important truths.

First, that the means which have been employed for the Christianization and civilization of the tribe, have been greatly blessed. Second, that the increase of these means will meet with final success. Third, that it has now become necessary that efficient and more than ordinary means should be employed.

Sensible of this last point, and wishing to do something for themselves, the Cherokee have thought it advisable that there should be established, a printing press and a seminary of respectable character; and for these purposes your aid and patronage are now solicited. They wish the types, as expressed in their resolution, to be composed of English letters and Cherokee characters. Those characters have now become extensively used in the nation; their religious songs are written in them; there is an astonishing eagerness in people of all classes and ages to acquire a knowledge of them; and the New Testament has been translated into their language. All this impresses on them the immediate necessity of procuring types. The most informed and judicious of our nation, believe that such a press would go further to remove ignorance, and her offspring superstition and prejudice, than all other means. The adult part of the nation will probably grovel on in ignorance and die in ignorance, without any fair trial upon them, unless the proposed means are carried into effect. The simplicity of this method of writing, and the eagerness to obtain a knowledge of it, are evinced by the astonishing rapidity with which it is acquired, and by the number who do so. It is about two years since its introduction, and already there are a great many who can read it. In the neighborhood in which I live, I do not recollect a male Cherokee, between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five, who is ignorant of this mode of writing.

But in connection with those for Cherokee characters, it is necessary to have types for English letters. There are a good many who already speak and read the English language, and can appreciate the advantages which would result from the publication of their laws and transactions in a well-conducted newspaper. Such a paper, comprising a summary of religious and political events, etc. on the one hand; and on the other, exhibiting the feelings, disposition, improvements, and prospects of the Indians; their traditions, their true character, as it once was and as it now is; the ways and means most likely to throw the mantle of civilization over all tribes; and such other matter as will tend to diffuse proper and correct impressions in regard to their condition—such a paper could not fail to create much interest in the American community, favorable to the aborigines, and to have a powerful influence on the advancement of the Indians themselves. How can the patriot or the philanthropist devise efficient means, without full and correct information as to the subjects of his labor. And I am inclined to think, after all that has been said of the aborigines, after all that has been written in narratives, professedly to elucidate the leading traits of their character, that the public knows little of that character. To obtain a correct and complete knowledge of these people, there must exist a vehicle of Indian intelligence, altogether different from those which have heretofore been employed. Will not a paper published in an Indian country, under proper and judicious regulations, have the desired effect? I do not say the Indians will produce learned and elaborate dissertations in explanation and vindication of their own character; but they may exhibit specimens of their intellectual efforts, of their eloquence, of their moral, civil, and physical advancement, which will do quite as much to remove prejudice and to give profitable information.

The Cherokees wish to establish their seminary upon a footing which will ensure to it all advantages that belong to such institutions in the states. Need I spend one moment in arguments, in favor of such an institution; need I speak one word of the utility, of the necessity, of an institution of learning; need I do more than simply to ask the patronage of benevolent hearts, to obtain that patronage.

When before did a nation of Indians step forward and ask for the means of civilization? The Cherokee authorities have adopted the measures already stated, with a sincere desire to make their nation an intelligent and virtuous people, and with a full hope that those who have already pointed out to them the road of happiness will now assist them to pursue it. With that assistance, what are the prospects of the Cherokees? Are they not indeed glorious, compared to that deep darkness in which the nobler qualities of their souls have slept. Yes, methinks I can view my native country, rising from the ashes of her degradation, wearing her purified and beautiful garments, and taking her seat with the nations of the earth. I can behold her sons bursting the fetters of ignorance and unshackling her from the vices of heathenism. She is at this instant, risen like the first morning sun, which grows brighter and brighter, until it reaches its fullness of glory.

She will become not a great, but a faithful ally of the United States. In times of peace she will plead the common liberties of America. In times of war her intrepid sons will sacrifice their lives in your defense. And because she will be useful to you in the coming time, she asks you to assist her in her present struggles. She asks not for greatness; she seeks not wealth; she pleads only for assistance to become respectable as a nation, to enlighten and ennoble her sons, and to ornament her daughters with modesty and virtue. She pleads for this assistance, too, because on her destiny hangs that of many nations. If she complete her civilization—then may we hope that all our nations will—then, indeed, may true patriots be encouraged in their efforts to make this world of the west, one continuous abode of enlightened, free, and happy people. . . .

There are, with regard to the Cherokees and other tribes, two alternatives; they must either become civilized and happy, or sharing the fate of many kindred nations, become extinct. If the general government continue its protection, and the American people assist them in their humble efforts, they will, they must rise. Yes, under such protection, and with such assistance, the Indian must rise like the Phoenix, after having wallowed for ages in ignorance and barbarity. But should this government withdraw its care, and the American people their aid, then, to use the words of a writer,

They will go the way that so many tribes have gone before them; for the hordes that still linger about the shores of Huron, and the tributary streams of the Mississippi, will share the fate of those tribes that once lorded it along the proud banks of the Hudson; of that gigantic race that are said to have existed on the borders of the Susquehanna; of those various nations that flourished about the Potomac and the Rappahannock, and that people the forests of the vast valley of Shenandoah. They will vanish like a vapor from the face of the earth, their very history will be lost in forgetfulness, and the places that now know them will know them no more.8

There is, in Indian history, something very melancholy, and which seems to establish a mournful precedent for the future events of the few sons of the forest, now scattered over this vast continent. We have seen everywhere the poor aborigines melt away before the white population. I merely speak of the fact, without at all referring to the cause. We have seen, I say, one family after another, one tribe after another, nation after nation, pass away; until only a few solitary creatures are left to tell the sad tale of extinction.

Shall this precedent be followed? I ask you, shall red men live, or shall they be swept from the earth? With you and this public at large, the decision chiefly rests. Must they perish? Must they all, like the unfortunate Creeks9 (victims of the un-Christian policy of certain persons), go down in sorrow to their grave?

They hang upon your mercy as to a garment. Will you push them from you, or will you save them? Let humanity answer

- 1. Acts 17:26.

- 2. Boudinot was educated at a mission school in Connecticut.

- 3. “Muskingum Sahta-goo” was possibly a reference to a massacre by Pennsylvania militia of Christian Indians that occurred in 1782 at a Moravian missionary settlement, Gnadenhutten, in what is now eastern Ohio. Hernán Cortes Cortés (1485–1547) led the Spanish conquest of Mexico.

- 4. Washington Irving, “Traits of Indian Character,” The Analectic, February 14, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: M. Thomas, 1814), 152.

- 5. George Gist, or Guess or Guest (Sequoyah) (c. 1770–1843).

- 6. A paraphrase perhaps of Matthew 22:29 or Mark 12:24.

- 7. Isaiah 35:1.

- 8. Washington Irving, “Traits of Indian Character,” in The Works of Washington Irving, vol. 2: The Sketchbook (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1861), 354–355.

- 9. A native people originally living in territory that is now part of Georgia.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.