Introduction

Having gained public notice from the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln was invited by Henry Pierce, head of a committee of Boston Republicans, to attend a festival in honor of Thomas Jefferson’s birthday. Lincoln was not able to attend the event but sent this letter instead, which was widely circulated in the Republican press. In the letter, he held up Jefferson’s principles as the “definitions and axioms” of a free society and articulated his view that agreement on first principles was a necessary precondition to having civic discourse. His praise of Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, rhetorically placed the Republican party as the true heir to the principles and values of American republicanism—a position often claimed by the Democratic Party. Both parties, of course, had a vested interest in claiming a lineage to Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was revered as a towering figure of the founding generation, and celebrations would be held on his birthday. Showing that Jefferson’s ideas and principles supported a given political party gave that party legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of Americans. This was particularly important for the still-nascent Republican Party that was trying to gain a foothold among the American electorate and in American politics.

—Eric C. Sands

Springfield, Ills., April 6, 1859

Messrs. Henry L. Pierce, & others.

Gentlemen

Your kind note inviting me to attend a Festival in Boston, on the 13th. Inst. in honor of the birth-day of Thomas Jefferson, was duly received. My engagements are such that I can not attend.

Bearing in mind that about seventy years ago, two great political parties were first formed in this country, that Thomas Jefferson was the head of one of them, and Boston the headquarters of the other, it is both curious and interesting that those supposed to descend politically from the party opposed to Jefferson should now be celebrating his birthday in their own original seat of empire, while those claiming political descent from him have nearly ceased to breathe his name everywhere.

Remembering too, that the Jefferson party was formed upon its supposed superior devotion to the personal rights of men, holding the rights of property to be secondary only, and greatly inferior, and then assuming that the so-called democracy of to-day, are the Jefferson, and their opponents, the anti-Jefferson parties, it will be equally interesting to note how completely the two have changed hands as to the principle upon which they were originally supposed to be divided.

The democracy of to-day hold the liberty of one man to be absolutely nothing, when in conflict with another man’s right of property. Republicans, on the contrary, are for both the man and the dollar; but in cases of conflict, the man before the dollar.

I remember once being much amused at seeing two partially intoxicated men engage in a fight with their great-coats on, which fight, after a long, and rather harmless contest, ended in each having fought himself out of his own coat, and into that of the other. If the two leading parties of this day are really identical with the two in the days of Jefferson and Adams, they have performed the same feat as the two drunken men.

But soberly, it is now no child’s play to save the principles of Jefferson from total overthrow in this nation.

One would start with great confidence that he could convince any sane child that the simpler propositions of Euclid are true; but, nevertheless, he would fail, utterly, with one who should deny the definitions and axioms. The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society. And yet they are denied and evaded, with no small show of success. One dashingly calls them “glittering generalities”; another bluntly calls them “self evident lies”; and still others insidiously argue that they apply only to “superior races.”

These expressions, differing in form, are identical in object and effect—the supplanting the principles of free government, and restoring those of classification, caste, and legitimacy. They would delight a convocation of crowned heads, plotting against the people. They are the van-guard—the miners, and sappers—of returning despotism. We must repulse them, or they will subjugate us.

This is a world of compensations; and he who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just God, can not long retain it.

All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.

Your obedient servant,

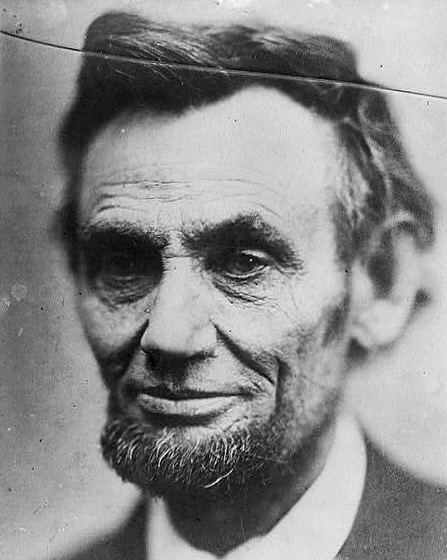

A. LINCOLN—