No related resources

Introduction

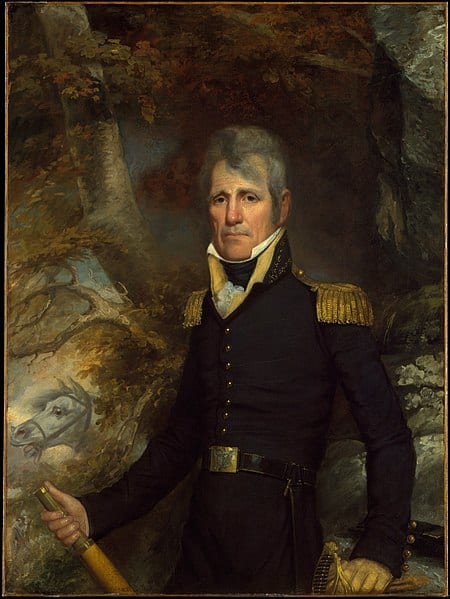

Perhaps the most divisive policy issue of Jackson’s presidency was the Second Bank of the United States. To set a political trap for Jackson, his opponents sought to re-charter the Bank early, before the election of 1832. Jackson vetoed it, making it the central issue of his reelection campaign, and, when he won, he declared that the people had delivered a mandate in support of his policy. Jackson then went on offense, ordering the Secretary of the Treasury William Duane to remove the Bank’s deposits and distribute them among state banks more friendly to his policies. When Duane refused, Jackson removed Duane from office and replaced him with Roger Taney.

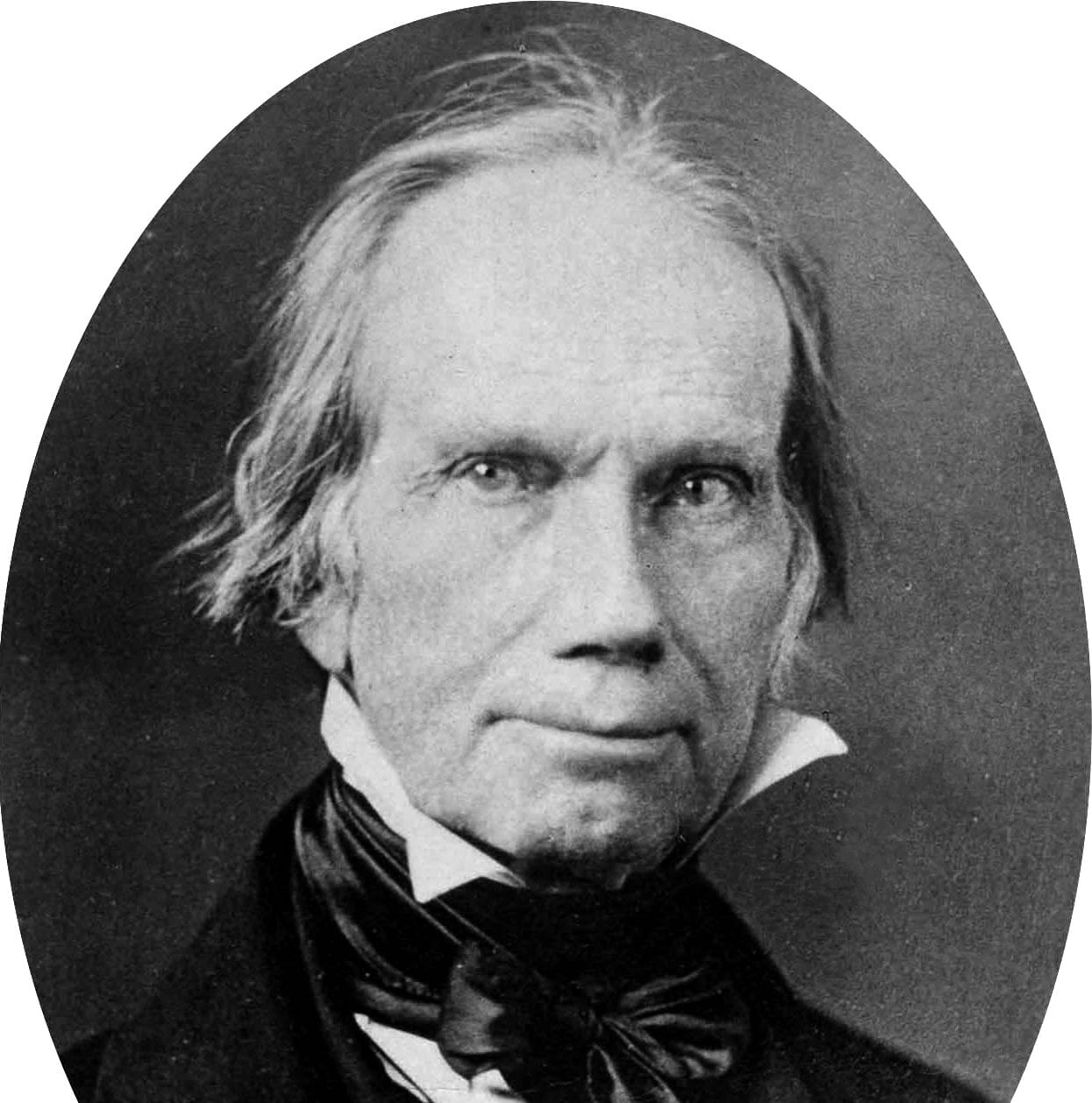

This was the first high profile removal of a department head since John Adams’ presidency, and it brought to a head a simmering controversy about removals in the Jackson administration. Jackson’s opponents revisited the constitutional arguments associated with removals and rejected the logic of the decision of 1789, in which Madison had successfully argued that the Constitution gives the power to the president alone. They argued that giving the president this power would interfere with Congress’s ability to make the laws, law that could for example direct the Treasury Secretary to disobey the president’s orders. In this speech before the Senate, Henry Clay proposes a new law that would reject the decision of 1789 and state clearly that Congress may set the terms of removal. Moreover, Clay lays the groundwork for the argument, later used in the Tenure of Office Act, requiring the president to share the power with the Senate (Johnson State of the Union (1867)). Notice also that Clay’s concerns were anticipated by Cato during the debate over ratification (Cato IV (1788)).

Source: Register of Debates, Senate, 23rd Congress, First Session (Washington, D.C: Gales and Seaton) 66, 834-36.

December 26, 1833

. . . At all events, he [President Andrew Jackson] seems to regard the issue of the election as an approbation of all constitutional opinions previously expressed by him, no matter in what ambiguous language. I differ, sir, entirely from the President. No such conclusions can be legitimately drawn from his re-election. He was re-elected from his presumed merits generally, and from the attachment and confidence of the people, and also from the unworthiness of his competitor.[1] The people had no idea, by that exercise of their suffrage, of expressing their approbation of all the opinions which the President held. Can it be believed that Pennsylvania, so justly denominated the keystone of our federal arch, which has been so steadfast in her adherence to certain great national interests, and, among others, to that of the Bank of the United States, intended, by supporting the re-election of the President, to reverse all her own judgments, and to demolish all that she had built up? The truth is, that the re-election of the President no more proves that the people had sanctioned all the opinion previously expressed by him, than, if he had had king’s evil or a carbuncle, it would demonstrate that they intended to sanction his physical infirmity.

But the president infers his duty to remove the deposits from the Constitution and the suffrages of the American people. As to the latter source of authority, I think it confers none. The election of a President, in itself, gives no power, but merely designates the person who, as an officer of the Government, is to exercise power granted by the Constitution and laws. In this sense, and in this sense only, does an election confer power. The President alleges a right in himself to superintend the operations of the executive departments from the Constitution and the suffrages of the people. Now, neither grants any such right. The Constitution gives him the power, and no other power, than to call upon the heads of each of the executive departments to give his opinion, in writing, as to any matter connected with his department. The issue of the election simply puts him in a condition to exercise that right. By the laws, not by the Constitution, all the departments, with the exception of that of the treasury, are placed under the direction of the President. And, by various laws, specific duties of the Secretary of the Treasury (such as contracting for loans, &c.) are required to be performed under the direction of the President. This is done from greater precaution; but his power, in these respects, is derived from the laws, and not from the Constitution. Even in regard to those departments other than that of the treasury, in relation to which by law, and not by the Constitution, a control is assigned to the Chief Magistrate, duties may be required of them, by the law, beyond his control, and for the performance of which their heads are responsible. This is true of the State Department, that which, above all others, is most under the immediate direction of the President….

March 7, 1834

Mr. Clay rose to present four resolutions, which he said he had prepared for the consideration of the Senate. It was not his (Mr. C’s) purpose now to engage in the discussion of them; but to propose that they be assigned to some convenient day, and it made the special order for that day. He wished, however, to accompany their presentation with one or two explanatory observations.

The first resolution asserted that the President, by the Constitution, is not invested with the power of removal from office at his pleasure. The second, declared that Congress is authorized by the Constitution to prescribe the tenure, terms, and conditions, of all offices established by law, where the Constitution itself has not affixed the tenure. The third, instructed the Committee on the Judiciary to inquire into the expediency of providing, by law, that removal from office shall not, in future, be made without the concurrence of the Senate; and, when that body is not in session, the power shall only be exercised provisionally, subject to the consideration of the Senate when it convenes. And the fourth directs an inquiry by the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, into the propriety of making provision by law for requiring the concurrence of the Senate in the appointment of all deputy postmasters, under certain restrictions.

These resolutions comprehend grave questions, of the highest importance, and which he (Mr. C) verily believed involved the just equilibrium between the several branches of the government, and the purity, if not the actual continuance, of the Government. The three first proceeded upon the assumption that the President is not clothed, by the Constitution, with the power of removal from office. That power, he was fully aware, by a vote of 34 to 20 in the House of Representatives, and by the casting vote of the Vice President, had, in the first Congress, been conceded to the chief Magistrate. Except in an incidental debate which arose in the Senate about four years ago, the propriety of that concession had never, he believed, been directly and deliberately considered. He had examined the Constitution with the utmost care and attention of which he was capable, and he felt firmly convinced that it did not grant any such power to the President. It was sustained in the first Congress as an implied or constructive power. And he felt himself authorized to pronounce that there was not another instance, among all the constructive powers, which had been controverted, of one which has so little foundation to rest upon as this power of removal at the pleasure of the President. The concession of it had been improvidently, in his opinion, made by the first Congress. It was made, probably, among other considerations, in consequence of the unbounded confidence reposed in the prudence, moderation, and wisdom, of the Father of his Country, the President of the United States [George Washington]. And it is remarkable that it was made with qualifications, which have been totally disregarded by the present Chief Magistrate.

The doctrines of the present administration, and the principles asserted by its supportersd, during the progress of the debate on the deposit question, maintain that all persons employed in the executive department of the Government, throughout all its ramifications, are bound to conform to the will of the President, no matter how contrary to their own judgement that will may be. The total number of persons, in all the various branches of the public service attached to the executive department of the Government, has been estimated at not less than forty thousand; and he presumed, from the size of the Blue Book,[2] that the estimate was rather below than above the mark. There are upwards of ten thousand deputy postmasters; and the number of persons employed in that single department, including postmasters, contractors, clerks, stage-drivers, and other carriers of the mail, is not probably short of thirty thousand. If this immense mass is to be actuated by one spirit, to obey one impulse, and to conform to the will of one man, it is not difficult to anticipate the arrival of the day when all the guaranties which we have supposed ourselves to posses for our liberties, will be utterly vain and unavailing. It has been a settled axiom in all free governments, and among all friends of civil liberty, that a standing army, in time of peace, is dangerous to the existence of freedom. A standing army is separate and distinct from the mass of society; dispersed and divided into different, and, perhaps, distant corps, stationed in their barracks or quarters. The amount of the danger arising from it can be seen, estimated, and guarded against. But what precautions can the community employ against the operations and influence of a standing army of forty thousand official incumbents? They are everywhere; in the cities and villages, at the taverns, at the cross-roads, and at every public place, mixing in the mass of society; and, if they have orders from headquarters, they will, without doubt, attempt to direct all the political movements of the country. In the possession of all the channels of intelligence, the mails and the post offices, how is it possible to resist their combined influence? Such a tremendous official corps, if a corrective be not applied, will, sooner or later, acquire the power to control and dispose of the succession of the Presidential office, as certainly as the less formidable Praetorian band of Rome[3] disposed, at will, of the imperial crown.

The object of the resolutions which he (Mr. C.) was about to present, was to invite a deliberate review of the constitutional powers of the President and of Congress; and to ascertain if the wisdom of our fathers had really rendered subservient to the will of one man, a vast power, capable of totally changing the character of the Government, and rendering it although in form a republic in fact a despotism. He hoped gentlemen who supported the executive prerogative would come to the discussion prepared to show, from the terms of the Constitution itself, that the power was granted to the President. He hoped that they would not entrench themselves behind one solitary precedent. Precedents were entitled, he admitted, to respect. They had been correctly defined to be the evidence of truth; but they were only evidence. And he did not think that a single precedent, without further examination into the Constitution, ought to be allowed to transform our free Government into a practical despotism.

If greater stability can be conferred on the tenure by which public offices are held, the functionary will be rendered less dependent on the capricious pleasure of one man. They will feel, as they ought to feel, that they have an equal right with other citizens to exercise the elective franchise, without responsibility to any man. Their continuance in office ought not to depend upon the independent manner of its exercise, but upon the ability, integrity, and fidelity, with which their official duties are performed. Filled, as most of the executive offices are, with partisans of the present administration, he (Mr. C.) could not be justly accused of any improper motive in proposing a measure which may give greater security to their abiding in them. The Constitution expressly provides for one and only one mode of removal from office—by impeachment. It may be expedient to authorize some more summary process in cases of ascertained unfitness or delinquency. The resolutions look to that object, but seek to provide a remedy against the possible prejudices, passions, or imperfections, of one man. He seriously and solemnly believed that the accomplishment of purpose contemplated by the resolutions, in some way or other, was essential to the purity and durability of the Government.

With these feelings, views, and opinions, he (Mr. C.) submitted the resolutions to the Senate, and moved that they be printed, and he made the special order of the day for the first Monday in April next. All of which was ordered accordingly.

The resolutions thus offered were the following:

- Resolved, That the Constitution of the United States does not vest in the President power to remove at his pleasure officers under the Government of the United States, whose offices have been established by law.

- Resolved, That, in all cases of offices created by law, the tenure of holding which is not prescribed by the Constitution, Congress is authorized by the Constitution to prescribe the tenure, terms, and conditions on which they are to be holden [held].

- Resolved, That the Committee on the Judiciary be instructed to inquire into the expediency of providing by law that in all instances of appointment to office by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, other than diplomatic appointment to office by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, other than diplomatic appointments, the power of removal shall be exercised only in concurrence with the Senate, and, when the Senate is not in session, that the President may suspend any such officer, communicating his reasons for the suspension to the Senate at its first succeeding session; and, if the Senate concur with him, the officer shall be removed, but if it do not concur with him, the officer shall be restored to office.

- Resolved, That the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads be instructed to inquire into the expediency of making provision by law for the appointment, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, of all deputy postmasters, whose annual emoluments exceed a prescribed amount.

After the transaction of some other business, the Senate adjourned over to Monday.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.