No related resources

Introduction

Former president Thomas Jefferson paid considerable attention to his successor’s war against “the English government and its piratical principles and practices,” as Jefferson put it. So determined was Jefferson to see America triumph in this struggle that in a letter dated June 29, 1812, he urged President Madison to endorse extralegal executions of domestic American opponents of the war.

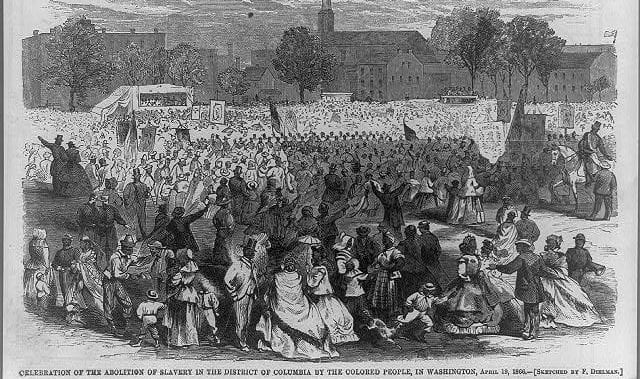

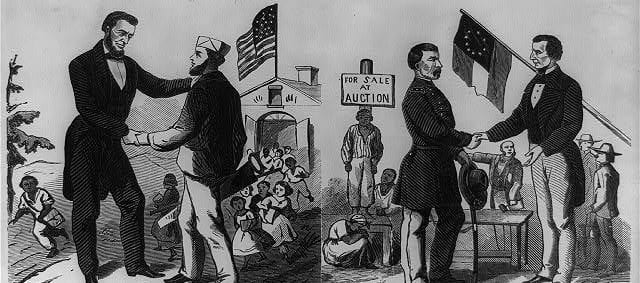

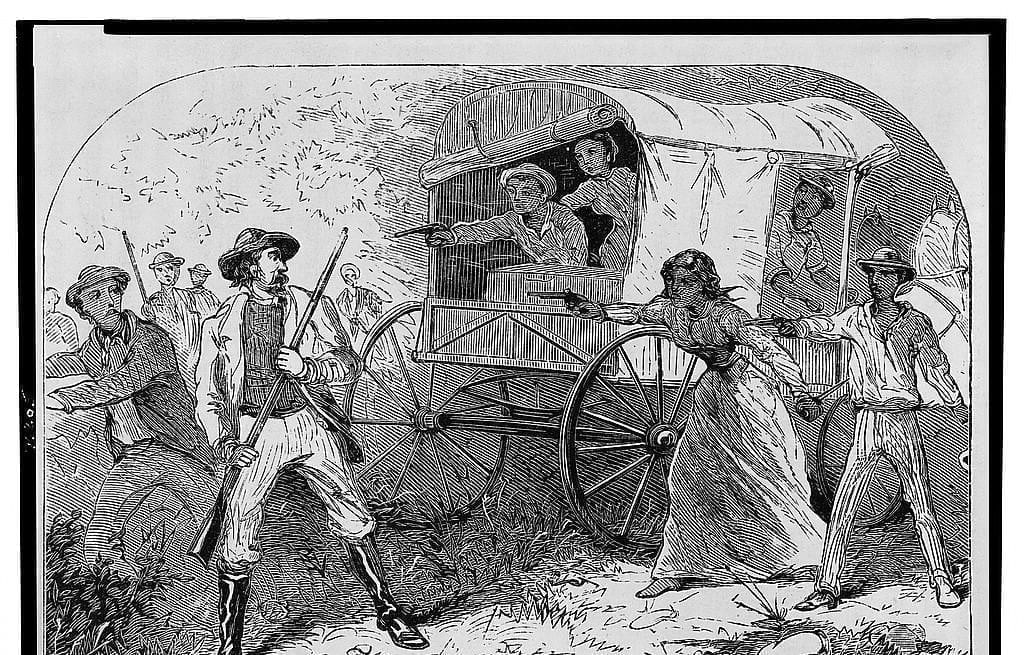

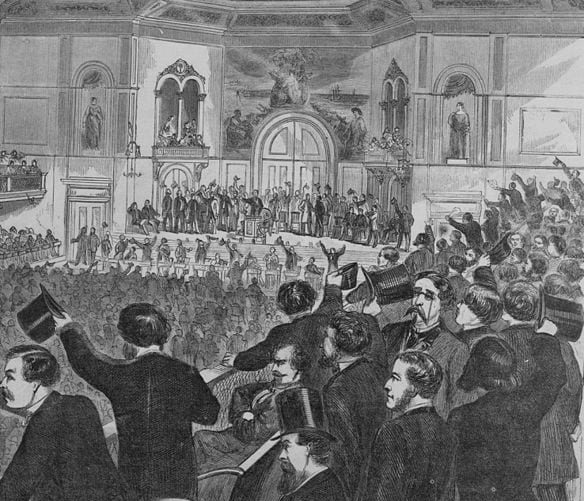

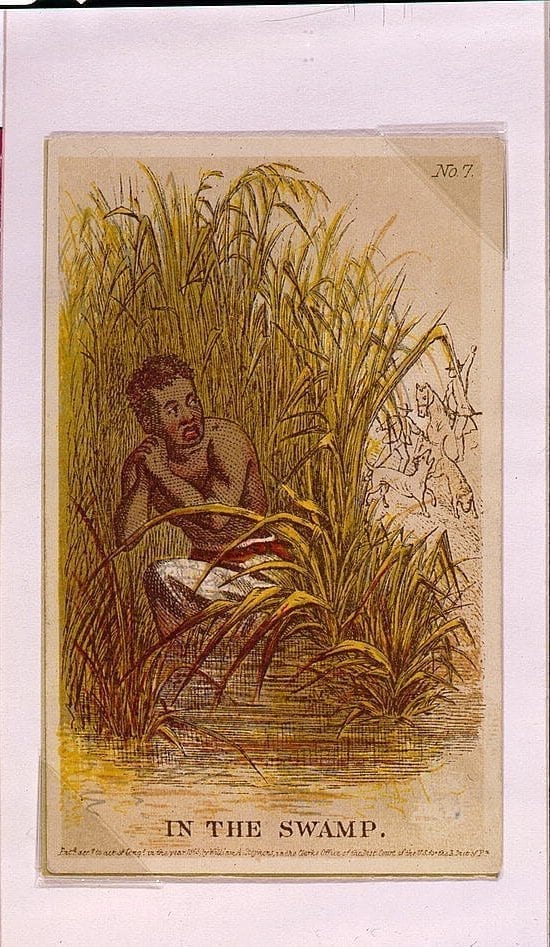

On August 24, 1814, British forces defeated American troops at the Battle of Bladensburg in Maryland. Following a hasty American retreat, British forces invaded Washington, DC, and proceeded to burn the Capitol, the White House, and a number of other government buildings. President Madison was fortunate to evade capture, having traveled out to Bladensburg to view the battle. This was the first and only time in the history of the United States that its capital was invaded.

Thomas Jefferson was probably not surprised when the news reached Monticello that the British had burned Washington. Jefferson had a remarkably jaundiced view of all things British, viewing that nation as on par with the Barbary Powers in terms of their “barbarism.” He had predicted at the outbreak of the war that the British were likely to burn major American cities but assumed the targets would be Boston and New York. At that time, he wrote that the United States should retaliate “not by expensive fleets” but by “hired incendiaries” whose hunger “will make them brave every risk for bread.” After hearing the news of the desecration of the republican seat of government, Jefferson picked up his pen to address the moral questions surrounding the use of retaliatory arson and hinted at possible targets if the United States followed this course of action.

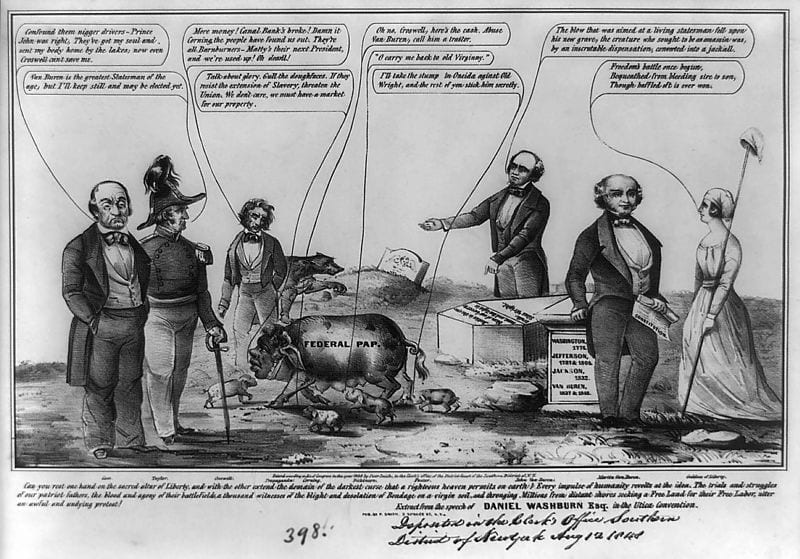

The propriety of resorting to means normally considered illegal or unethical has vexed American policymakers throughout the nation’s existence, particularly during wartime. Some American presidents have found these types of actions distasteful, including George Washington, who bemoaned the necessity of employing “ambiguous characters” to conduct clandestine operations. But as Jefferson once put it to a correspondent, John B. Colvin, in September 1810, “the laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation. To lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to written law, would be to lose the law itself, with life, liberty, property and all those who are enjoying them with us; thus absurdly sacrificing the end to the means.”

The same moral considerations that Jefferson weighed in this letter confronted American policymakers throughout the twentieth century. Clandestine operations, as Secretary of State Dean Rusk (1909–1994) observed, are carried out in “the back alleys of the world” and are not for the fainthearted. A presidential commission created by Dwight Eisenhower (1890–1969) concluded in 1954: “It is now clear that we are facing an implacable enemy whose avowed objective is world domination by whatever means and at whatever cost. … There are no rules in such a game. … If the United States is to survive, long-standing concepts of ‘fair play’ must be reconsidered.” Vice President Dick Cheney would echo this theme in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, arguing that “we also have to work … the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies.” Critics contend that by embracing the “dark side” the nation abandons the core of its creed and begins to mimic the worst features of despotic forms of government. Defenders of such practices argue that necessity requires such steps and that elected officials in a republic have an obligation to preserve and protect the political order with whose care they have been entrusted.

“Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Cooper, 10 September 1814,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-07-02-0471.

… You will say, we have been devastated in the meantime. True. some of our public buildings have been burnt, and some scores of individuals on the tide waters have lost their moveable property and their houses. I pity them; and execrate the barbarians who delight in unavailing mischief. But these individuals have their lands and their hands left. They are not paupers. They have still better means of subsistence than 24/25 of the people of England. Again, the English have burnt our Capitol and president’s house by means of their force. We can burn their St. James’s and St. Paul’s,1 by means of our money, offered to their own incendiaries, of whom there are thousands in London who would do it rather than starve. But it is against the laws of civilized warfare to employ secret incendiaries. Is it not equally so to destroy the works of art by armed incendiaries? Bonaparte, possessed at times of almost every capital of Europe, with all his despotism & power, injured no monument of art. If a nation, breaking thro’ all the restraints of civilized character, uses its means of destruction (power, for example) without distinction of objects, may we not use our means (our money and their pauperism) to retaliate their barbarous ravages? Are we obliged to use, for resistance, exactly the weapons chosen by them for aggression? When they destroyed Copenhagen by superior force,2 against all the laws of God and man, would it have been unjustifiable for the Danes to have destroyed their ships by torpedoes? Clearly not. And they and we should now be justifiable in the conflagration of St. James’s and St. Paul’s. And if we do not carry it into execution, it is because we think it more moral and more honorable to set a good example, than follow a bad one….

Resolutions Adopted by the Hartford Convention

January 04, 1815

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.