No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

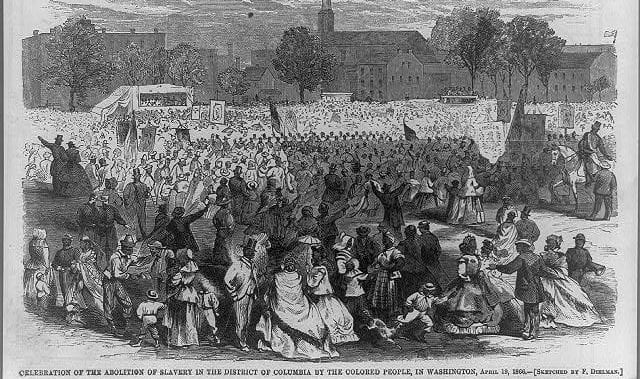

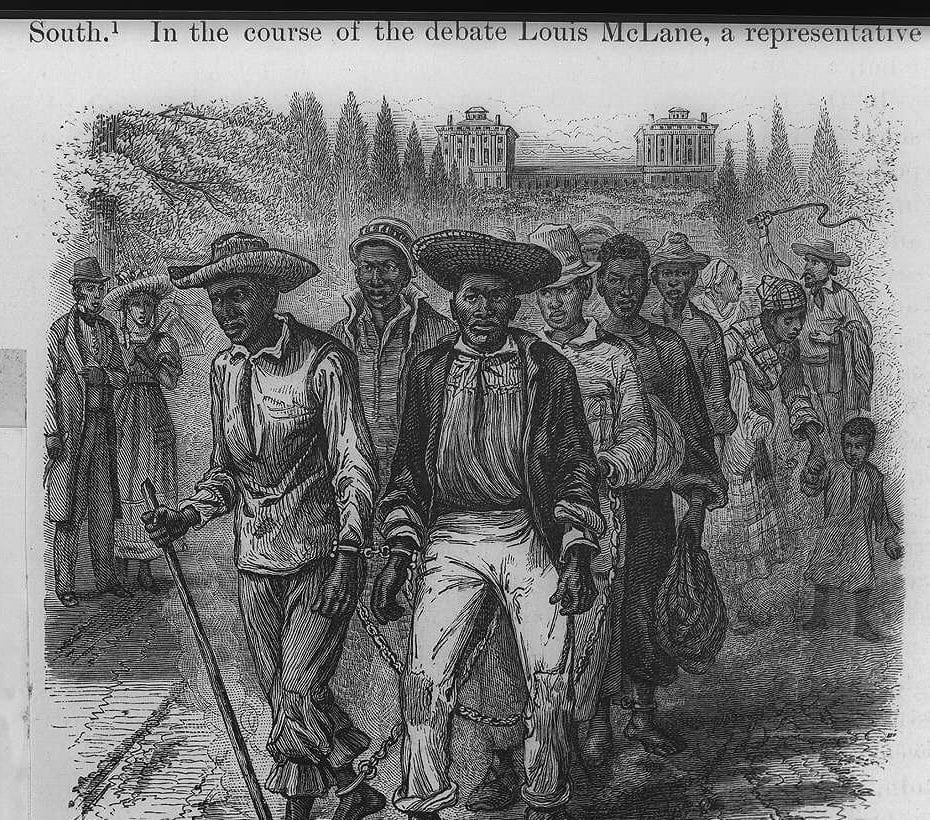

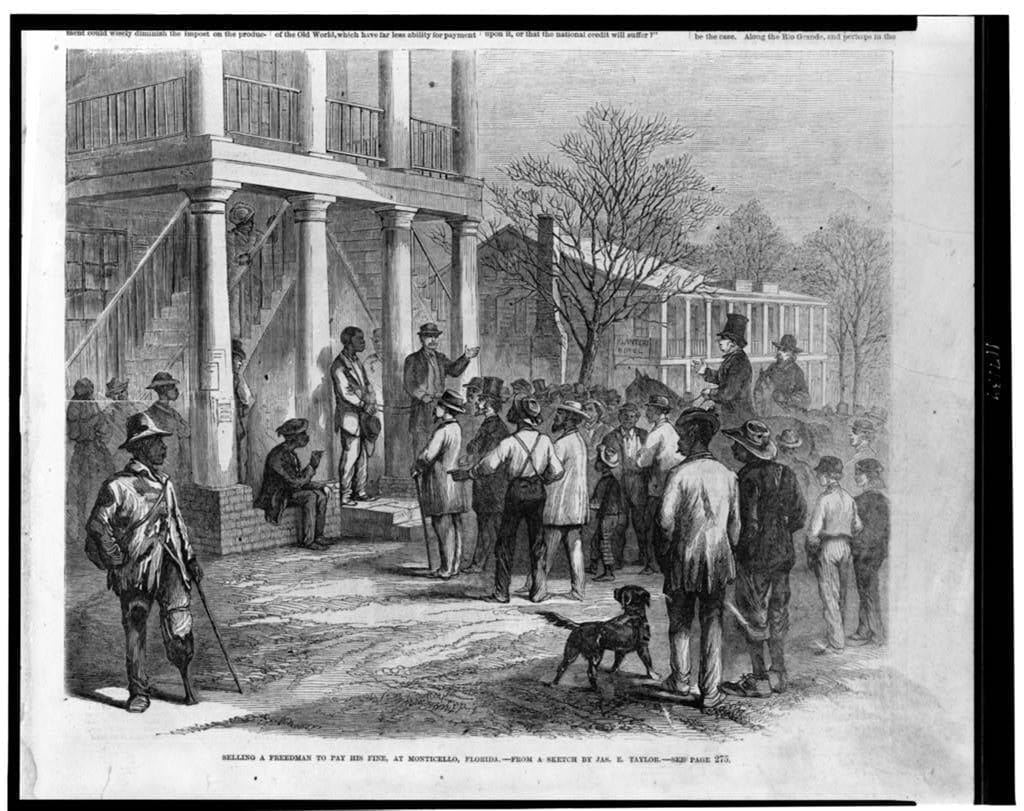

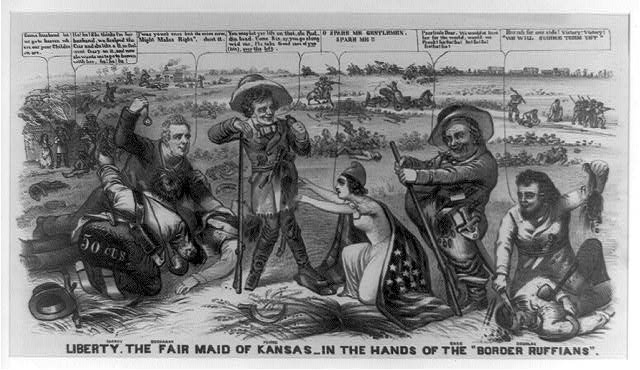

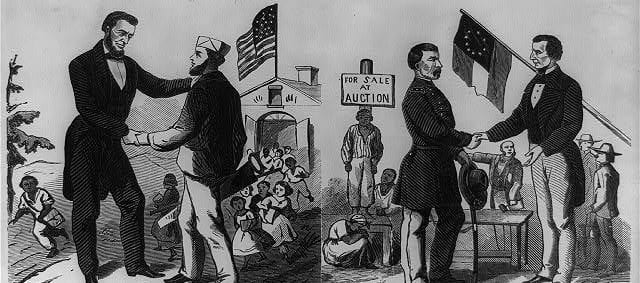

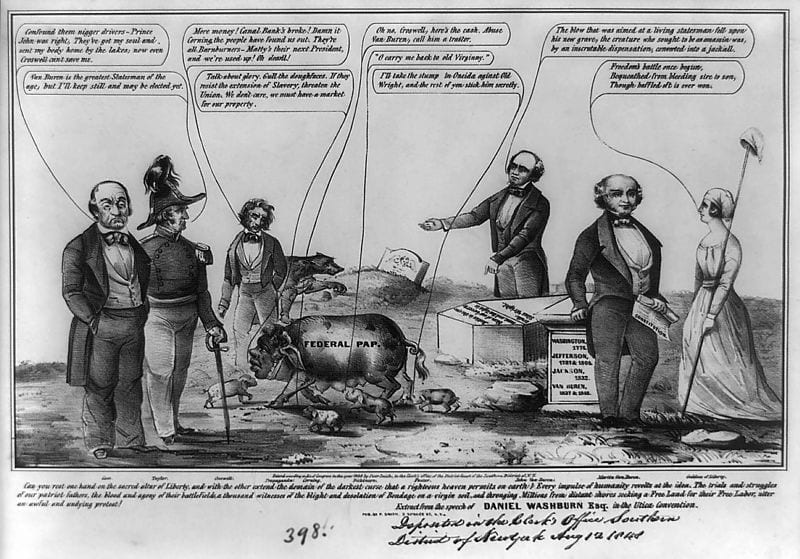

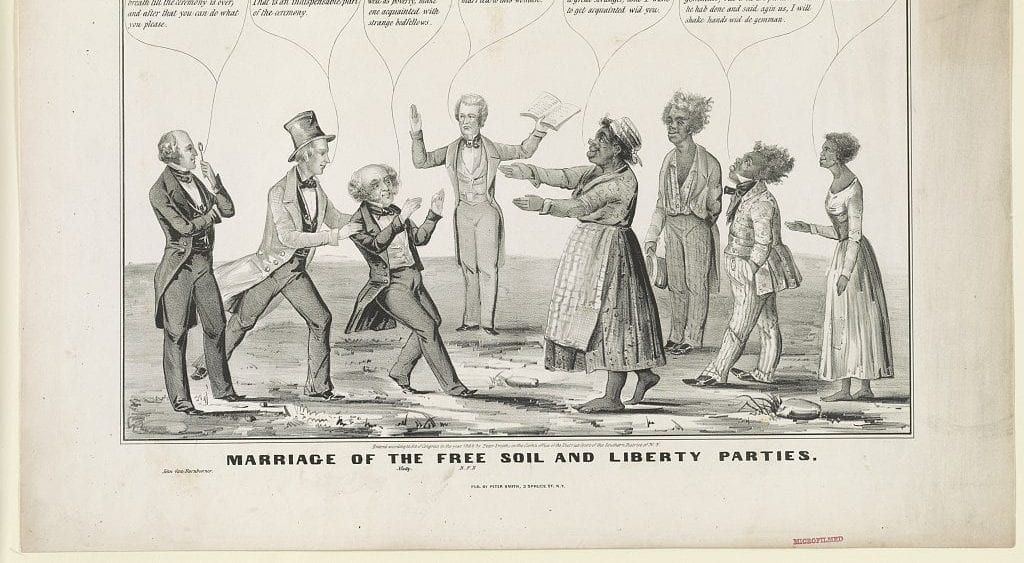

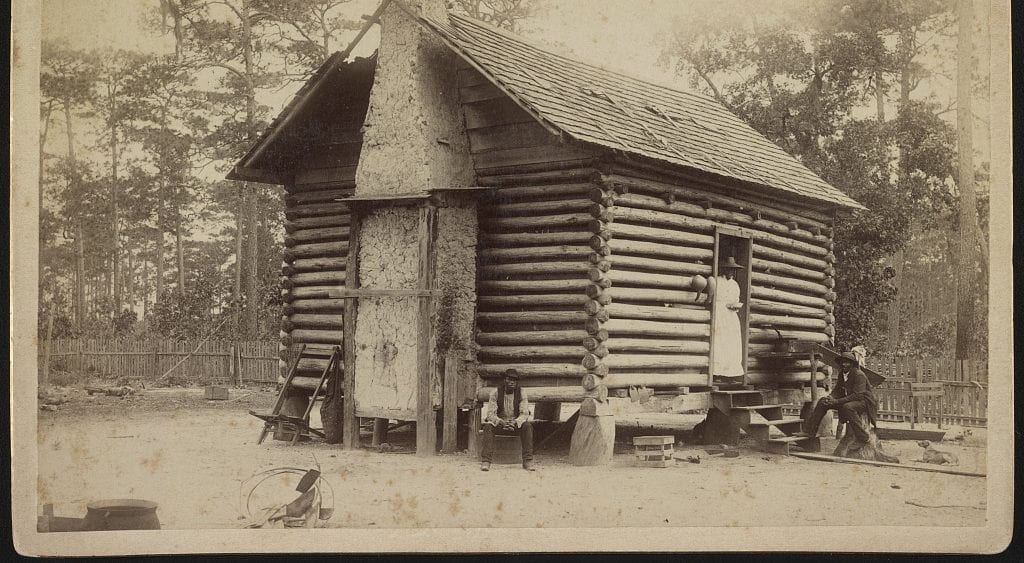

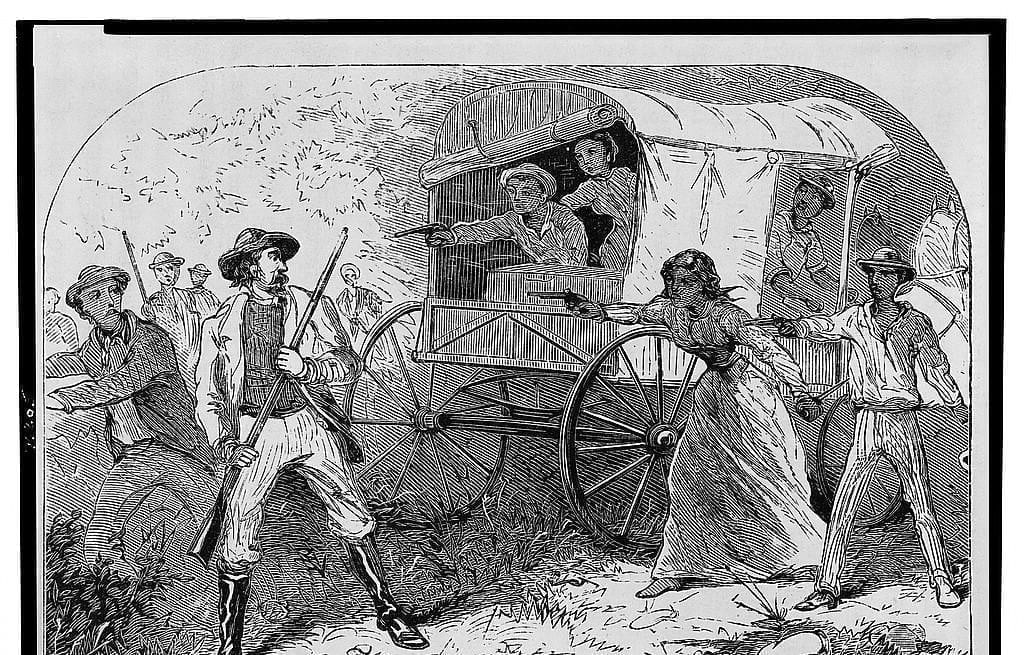

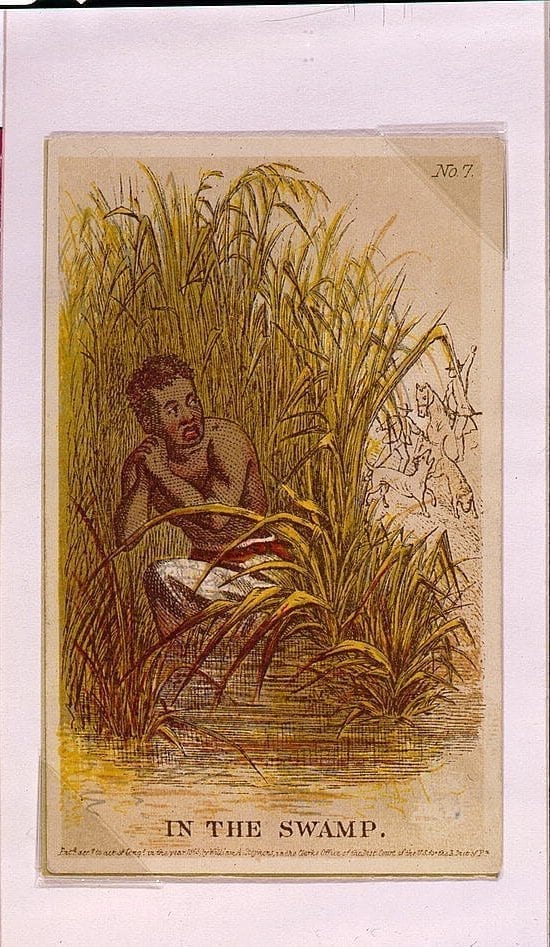

By 1830, slavery had become very much a regional, as opposed to a national institution (see Number of Slaves in the Territory Enumerated, 1790 to 1850). The New England and Middle States had, through a combination of gradual abolition and immediate emancipation measures, dramatically decreased the number of slaves in their territories, while the Southern states had increased their reliance upon slave labor in the production of various cash crops, chief among them “King Cotton.” Nevertheless, there were individuals in both sections of the country who recognized the need for continued prudential reform. In December 1833, dozens of Northern activists met in Philadelphia to found the American Anti-Slavery Society. Although the group called for the immediate and uncompensated emancipation of all enslaved persons, they also denounced the use of violent resistance – an important concession to Southern slaveholders fearful of additional armed uprisings like Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831). Southern activist Angelina Grimke addressed similar fears in her Appeal to the Christian Women of the South. Grimke urged Southern women to speak out against slavery as an unjust and oppressive system, but also counseled them to encourage patience and submission on the part of their slaves until freedom was obtained.

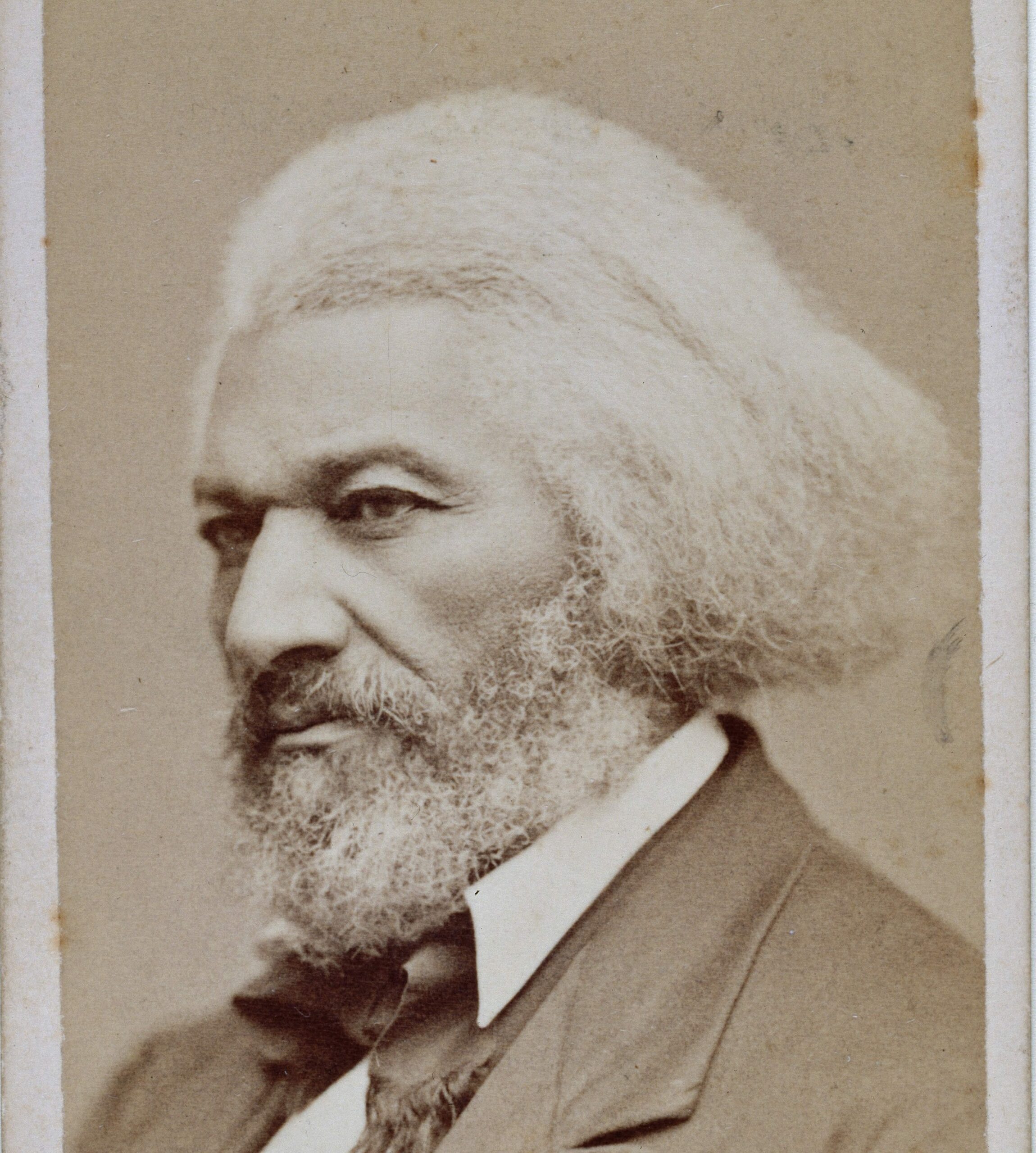

As the decade wore on, such moderate positions were eclipsed by a hardening of views and greater entrenchment on both sides. Southern newspapers carried advertisements for runaway slaves that described them in horrific, brutalizing terms, which Northern publishers delighted in reprinting to highlight the inhumanity of slaveholders. In 1849, Frederick Douglass – a self-emancipated former slave – emphatically denounced all plans related to abolition that did not also aim at ending racial prejudice and lead towards the formal equality of blacks and whites. Yet five years later, Southern sociologist George Fitzhugh was still defending race-based slavery as positive good, arguing that it benefited the slave as well as the owner.

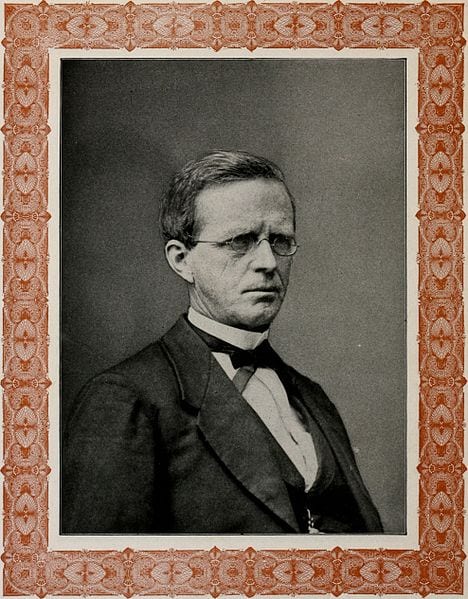

Frederick Douglass, “The American Colonization Society,” The Liberator, June 8, 1849. Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was a former slave who became a leading abolitionist.

. . . It is because the American Colonization Society1 cherishes and fosters this feeling of hatred against the black man, that I am opposed to it. And I am especially disposed to speak out my opposition to this colonization scheme to-night, because not only of the renewed interest excited in the colonization scheme by the efforts of Henry Clay and others, but because there is a lecturer in the shape of the Rev. Mr. Miller, of New Jersey, now in England, soliciting funds for our expatriation from this country, and going about trying to organize a society, and to create an impression in favor of removing us from this country. I would ask you, my friends, if this is not mean and impudent in the extreme, for one class of Americans to ask for the removal of another class? I feel, sir, I have as much right in this country as any other man. I feel that the black man in this land has as much right to stay in this land as the white man. Consider the matter in the light of possession in this country. Our connection with this country is contemporaneous with your own. From the beginning of the existence of this people, as a people, the colored man has had a place upon the American soil. To be sure, he was not driven from his home in pursuit of a greater liberty than he enjoyed at home, like the Pilgrim fathers; but in the same year that the Pilgrims were landing in this State, slaves were landing on the James River, in Virginia. We feel on this score, then, that we have as much right here as any other class of people.

We have other claims to being regarded and treated as American citizens. Some of our number have fought and bled for this country, and we only ask to be treated as well as those who have fought against it. We are lovers of this country, and we only ask to be treated as well as the haters of it. We are not only told by Americans to go out of our native land to Africa, and there enjoy our freedom – but Irishmen newly landed on our soil, who know nothing of our institutions, nor of the history of our country, whose toil has not been mixed with the soil of the country as ours – have the audacity to propose our removal from this, the land of our birth. For my part, I mean, for one, to stay in this country; I have made up my mind to live among you. I had a kind offer, when I was in England, of a little house and lot, and the free use of it, on the banks of the river Eden. I could easily have stayed here, if I had sought for ease, undisturbed, unannoyed by American skin-aristocracy; for it is an aristocracy of skin – those passengers on board the Alida only got their dinners that day in virtue of their color; if their skins had been of my color, they would have had to fast all day. Whatever denunciations England may be entitled to on account of their treatment of Ireland and her own poor, one thing can be said of her, that no man in that country, or in any of her dominions, is treated as less than a man of account of his complexion. I could have lived there; but when I remembered this prejudice against color, as it is called, and slavery, and saw the many wrongs inflicted on my own people at the North that ought to be combated and put down, I felt a disposition to lay aside ease, to turn my back on the kind offer of my friends, and to return among you – deeming it more noble to suffer along with my colored brethren, and meet these prejudices, that to live at ease, undisturbed, on the other side of the Atlantic. I had rather be here now, encountering this feeling, bearing my testimony against it, setting it at defiance, than to remain in England undisturbed. I have made up my mind wherever I go, I shall go as a man, not as a slave. When I go on board of your steamboats, I shall always aim to be courteous and mild in my deportment towards all with whom I come in contact, at the same time firmly and constantly endeavoring to assert my equal right as a man and a brother.

But the Colonization Society says this prejudice can never be overcome – that it is natural – God has implanted it. Some say so; others declare that it can only be removed by removing us to Liberia.2 I know this is false, from my own experience in this country. I remember that, but a few years ago, upon the railroads from New Bedford and Salem and in all parts of Massachusetts, a most unrighteous and proscriptive rule prevailed, by which colored men and women were subjected to all manner of indignity in the use of those conveyances. Anti-slavery men, however, lifted up their testimony against this principle from year to year; and from year to year, he whose name cannot be mentioned without receiving a round of applause, Wendell Phillips3 went abroad, exposing this proscription in the light of justice. What is the result? Not a single railroad can be found in any part of Massachusetts, where a colored man is treated and esteemed in any other light than that of a man and a traveler. Prejudice has given way and must give way. The fact that it is giving way proves that this prejudice is not invincible. The time was when it was expected that a colored man, when he entered a church in Boston, would going into the Jim Crow pew – and I believe such is the case now, to a large extent; but then there were those who would defend the custom. But you can scarcely get a defender of this proscription in New England now.

The history of the repeal of the intermarriage law shows that the prejudice against color is not invincible. The general manner in which white persons sit with colored persons shows plainly that the prejudice against color is not invincible. When I first came here, I felt the greatest possible diffidence of sitting with whites. I used to come up from the shipyard, where I worked, with my hands hardened with toil, rough and uncomely, and my movements awkward (for I was unacquainted with the rules of politeness), I would shrink back, and would not have taken my meals with the whites had they not pressed me to do so. Our president, in his earlier intercourse with me, taught me, by example his abhorrence of this prejudice. He has, in my presence, stated to those who visited him, that if they did not like to sit at the table with me, they could have a separate one for themselves.

The time was, when I walked through the streets of Boston, I was liable to insult if in company with a white person. To-day I have passed in company with my white friends, leaning their arm and they on mine, and yet the first word from any quarter on account of the color of my skin I have not heard. It is all false, this talk about the invincibility of prejudice against color. If any of you have it, and no doubt some of you have, I will tell you how to get rid of it.

Commence to do something to elevate and improve and enlighten the colored man, and your prejudice will begin to vanish. The more you try to make a man of the black man, the more you will begin to think him a man. . . .

- 1. The American Colonization Society was founded in 1816 with the goal of relocating freed slaves to Africa

- 2. Located on the western coast of Africa, Liberia was founded as a colony by the ACS in 1822; it became independent in 1847.

- 3. Wendell Phillips (1811–1884) was a lawyer, abolitionist, advocate of women’s rights and, after the Civil War, of the rights of Native Americans.

Uses and Abuses of the Bible

November 04, 1849

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.