In Douglass’s opinion, why did enslaved people sing? What details about the life of enslaved people included in this passage might support Douglass interpretation of the enslaved people’s singing?

No related resources

Introduction

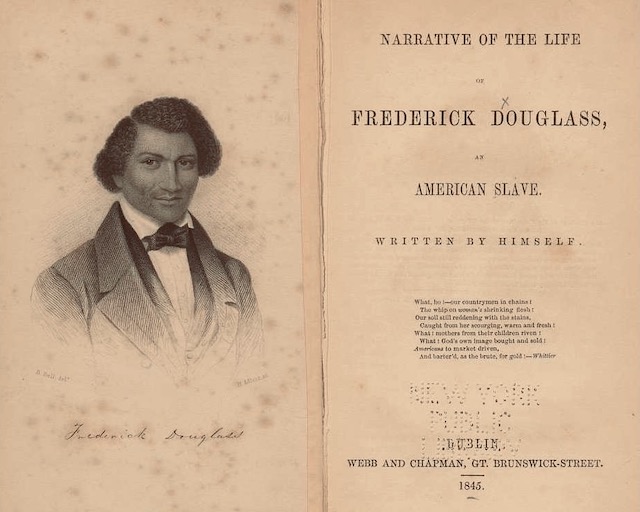

Frederick Douglass had established himself as the leading African American abolitionist of his generation before the Civil War began. Born into slavery in Talbot County, MD in 1818, he escaped to New England twenty years later where he met fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and began speaking to white audiences about his experiences as a slave. He wrote the first of three autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of a Slave, in 1845 to counter criticism that his story was contrived. Some whites, who heard Douglass speak, or read newspaper accounts of his talks, expressed doubts that a black man, especially a former slave, could be as intelligent and articulate as Douglass. They speculated that Douglass’s white sponsors wrote his speeches and coached him on his presentations. His detailed descriptions of enslaved life and straight-forward prose silenced many doubters. They also made him a marked man. Legally, he remained a fugitive slave, subject to arrest and re-enslavement. Fearing capture, Douglass sailed to England in 1845 where he continued speaking against American slavery. Friends purchased his freedom while he was in England. He returned to the United States in 1847 and continued his crusade to end American slavery.

Douglass begins his Narrative by sketching details of his birth to an enslaved woman named Harriet Bailey. He had “no accurate knowledge of” his age because the birthdays of enslaved persons were seldom recorded. He later learned he was “about seventeen years old in” 1835 so many scholars date his birth year as 1818. Douglass knew his father to be a white man and suspected his father was his enslaver, Aaron Anthony. At age six, he was sent to William Lloyd’s plantation to prepare for a life as a field hand. Following the death of his mother and grandmother, he was reassigned to the home of Thomas and Sophia Auld in Baltimore. It was a fortuitous change for young Frederick. In Baltimore, Douglass taught himself to read and write and began developing the rhetorical skills that were to bring him fame as an abolitionist.

In this passage from Chapter II Narrative of the Life of a Slave, Douglass describes the type of provisions given to the enslaved people on William Lloyd’s plantations, the sleeping arrangements, and the work expectations for the field hands. Yet, the most poignant part of the passage is about the enslaved people’s singing. Enslaved people walked to the Great House Farm, the headquarters for Lloyd’s largest plantation, to receive regular allowances of food and clothing. They sang on the way as they sang in the field, from sorrow and from happiness, whatever mood carried the moment. Douglass disputed the claim that he heard in the North that the enslaved people’s singing was proof that they were happy and content with their enslavement. “It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake,” he wrote. He compared the songs of the enslaved to tears of an aching heart.

Source: Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (Boston: the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845). https://www.google.com/books/edition/Narrative_of_the_Life_of_Frederick_Dougl/ds08RYrDBPIC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

…Colonel Lloyd kept from three to four hundred slaves on his home plantation, and owned a large number more on the neighboring farms belonging to him. …

…The men and women slaves received, as their monthly allowance of food, eight pounds of pork, or its equivalent in fish, and one bushel of corn meal. Their yearly clothing consisted of two coarse linen shirts, one pair of linen trousers, like the shirts, one jacket, one pair of trousers for winter, made of coarse negro cloth, one pair of stockings, and one pair of shoes; the whole of which could not have cost more than seven dollars. The allowance of the slave children was given to their mothers, or the old women having the care of them. The children unable to work in the field had neither shoes, stockings, jackets, nor trousers, given to them; their clothing consisted of two coarse linen shirts per year. When these failed them, they went naked until the next allowance-day. Children from seven to ten years old, of both sexes, almost naked, might be seen at all seasons of the year.

There were no beds given the slaves, unless one coarse blanket be considered such, and none but the men and women had these. This, however, is not considered a very great privation. They find less difficulty from the want of beds, than from the want of time to sleep; for when their day’s work in the field is done, the most of them having their washing, mending, and cooking to do, and having few or none of the ordinary facilities for doing either of these, very many of their sleeping hours are consumed in preparing for the field the coming day; and when this is done, old and young, male and female, married and single, drop down side by side, on one common bed,—the cold, damp floor,—each covering himself or herself with their miserable blankets; and here they sleep till they are summoned to the field by the driver’s horn. At the sound of this, all must rise, and be off to the field. There must be no halting; every one must be at his or her post; and woe betides them who hear not this morning summons to the field; for if they are not awakened by the sense of hearing, they are by the sense of feeling: no age nor sex finds any favor. Mr. Severe, the overseer, used to stand by the door of the quarter, armed with a large hickory stick and heavy cowskin, ready to whip any one who was so unfortunate as not to hear, or, from any other cause, was prevented from being ready to start for the field at the sound of the horn. …

…The home plantation of Colonel Lloyd wore the appearance of a country village. All the mechanical operations for all the farms were performed here. The shoemaking and mending, the blacksmithing, cartwrighting, coopering, weaving, and grain-grinding, were all performed by the slaves on the home plantation. The whole place wore a business-like aspect very unlike the neighboring farms. The number of houses, too, conspired to give it advantage over the neighboring farms. It was called by the slaves the Great House Farm. Few privileges were esteemed higher, by the slaves of the out-farms, than that of being selected to do errands at the Great House Farm. …

…The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow-slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out— if not in the word, in the sound;—and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this, when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:—

“I am going away to the Great House Farm!

O, yea! O, yea! O!”

This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. If any one wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd’s plantation, and, on allowance-day, place himself in the deep pine woods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul,—and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because “there is no flesh in his obdurate heart.”

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.