No related resources

Introduction

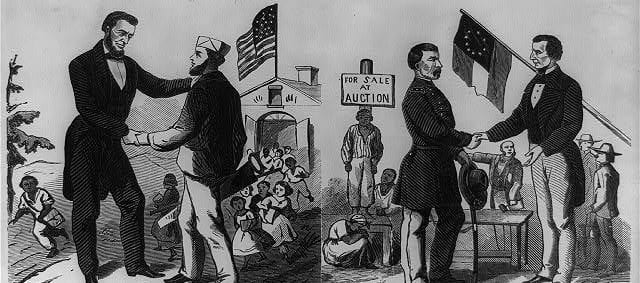

Born Isabel Baumfree, Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) escaped from slavery in New York State in 1826, roughly a year before she would have been freed under the state’s recently adopted emancipation law. She found refuge in the home of the Van Wagener’s, a white family who offered to reimburse her master for the year of her lost labor; he accepted, and Baumfree remained with the family until 1827 when she became legally free. During this period, she experienced a religious awakening that led her from the legalistic beliefs of her childhood to a fervent and personal relationship with God. The timing of this episode was prophetic, for it happened on the very day that Baumfree had determined to return herself to slavery out of loneliness.

Baumfree’s religious fervor did not abate after this episode; in 1843, she had another vision, in which she heard the Lord commanding her to travel the nation as an itinerant gospel speaker and adopted the name Sojourner Truth. Her testimony on these occasions was so powerful that Olive Gilbert asked her to work with him to publish it and make it more accessible to those unable to hear her speak in person.

Source: Olive Gilbert, ed., Narrative of Sojourner Truth (Boston, 1850), 59-73.

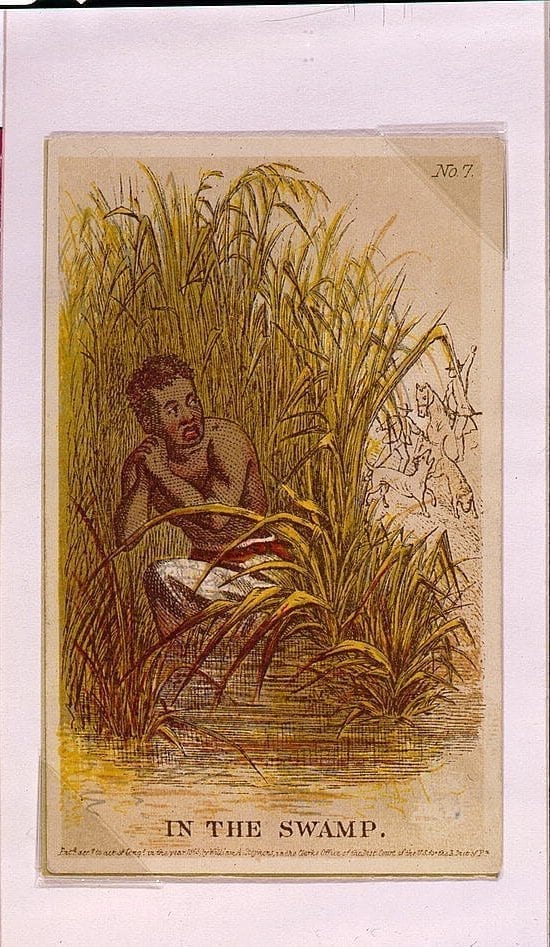

. . . She had no trouble now; her every prayer had been answered in every minute particular. She had been delivered from her persecutors and temptations, her youngest child had been given her, and the others she knew she had no means of sustaining if she had them with her, and was content to leave them behind. Their father, who was much older than Isabel, and who preferred serving his time out in slavery, to the trouble and dangers of the course she pursued, remained with and could keep an eye on them—though it is comparatively little that they can do for each other while they remain in slavery. . . .

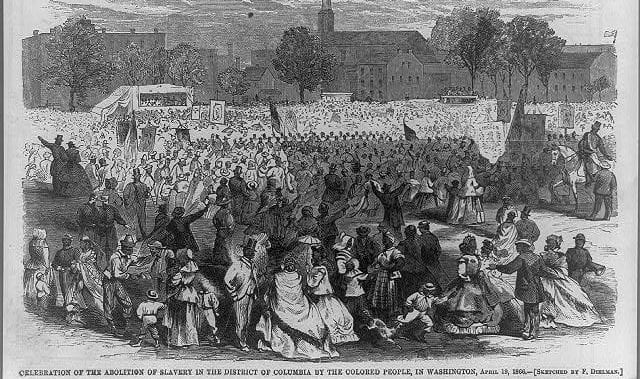

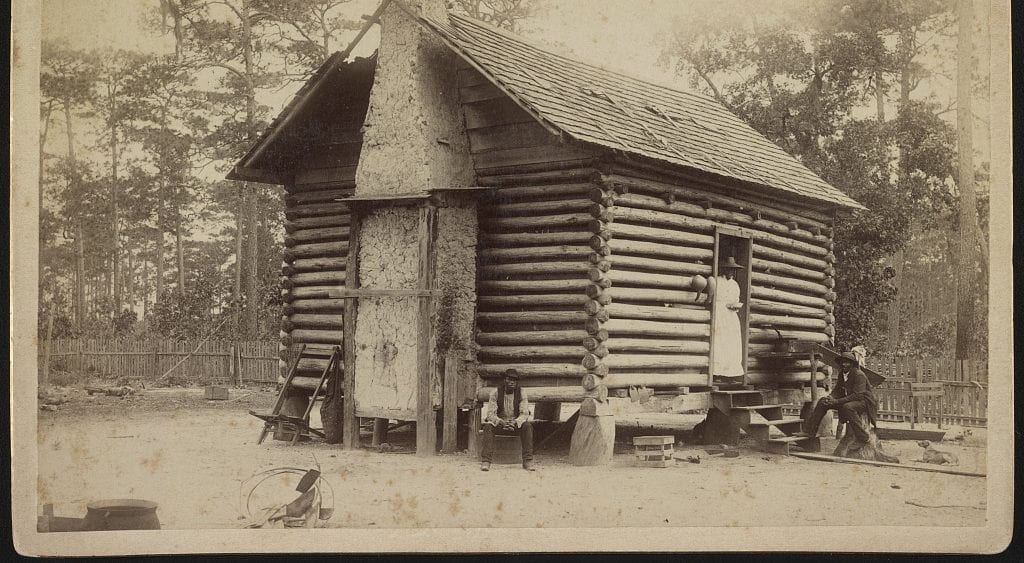

The slaves in this country have ever been allowed to celebrate the principal, if not some of the lesser festivals observed by the Catholics and Church of England;—many of them not being required to do the least service for several days, and at Christmas they have almost universally an entire week to themselves, except, perhaps, the attending to a few duties, which are absolutely required for the comfort of the families they belong to. If much service is desired, they are hired to do it, and paid for it as if they were free. The more sober portion of them spend these holidays in earning a little money. Most of them visit and attend parties and balls, and not a few of them spend it in the lowest dissipation. This respite from toil is granted them by all religionists, of whatever persuasion, and probably originated from the fact that many of the first slaveholders were members of the Church of England.

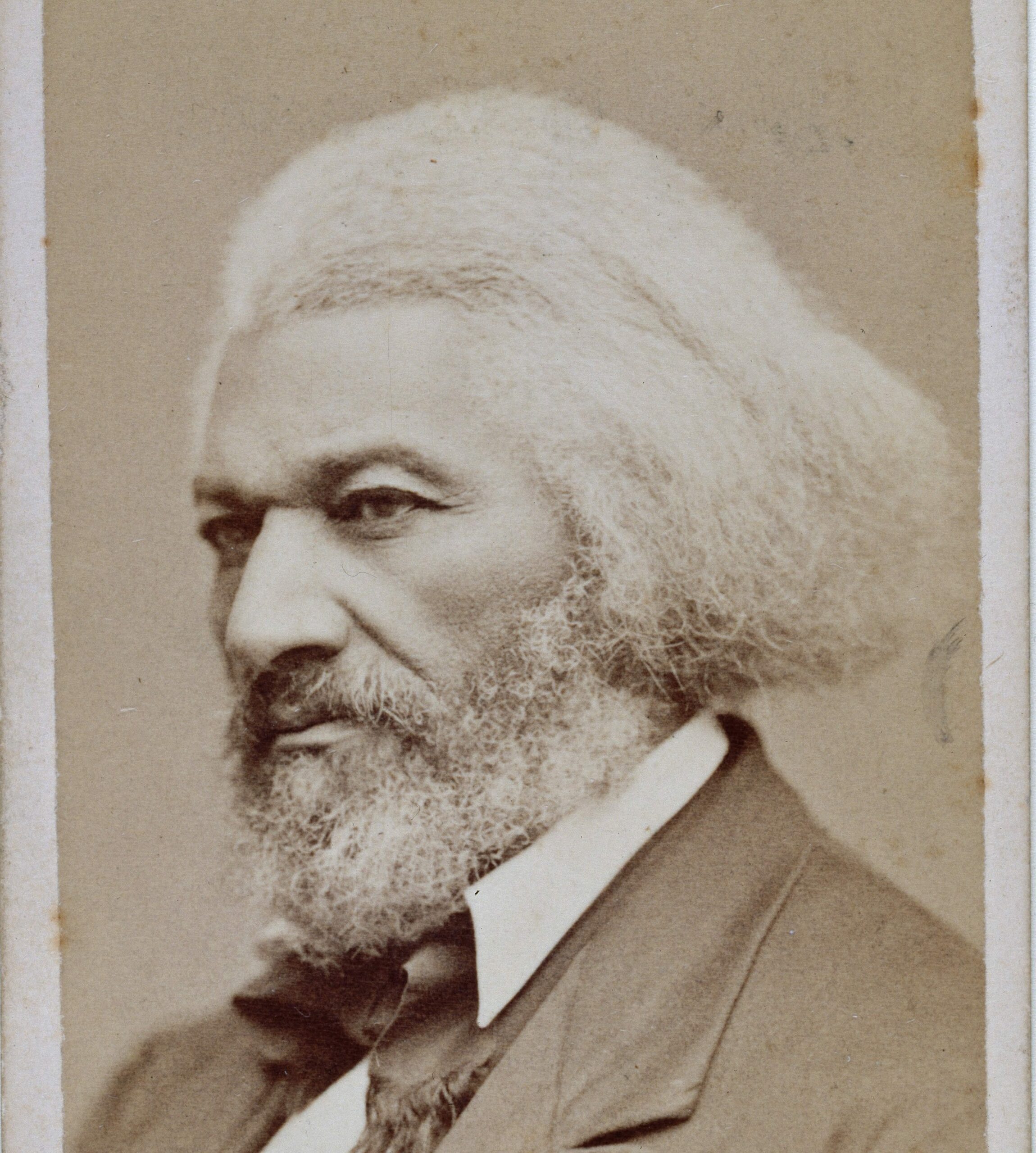

Frederick Douglass,[1] who has devoted his great heart and noble talents entirely to the furtherance of the cause of his down-trodden race, has said

From what I know of the effect of their holidays upon the slave, I believe them to be among the most effective means, in the hands of the slaveholder, in keeping down the spirit of insurrection. Were the slaveholders at once to abandon this practice, I have not the slightest doubt it would lead to an immediate insurrection among the slaves. These holidays serve as conductors, or safety-valves, to carry off the rebellious spirit of enslaved humanity. But for these, the slave would be forced up to the wildest desperation; and woe betide the slaveholder, the day he ventures to remove or hinder the operation of those conductors! I warn him that, in such an event, a spirit will go forth in their midst, more to be dreaded than the most appalling earthquake.[2]

When Isabella had been at Mr. Van Wagener’s a few months, she saw in prospect one of the festivals approaching. She knows it by none but the Dutch name, Pinkster, as she calls it—but I think it must have been Whitsuntide, in English. She says she “looked back into Egypt,” and everything looked “so pleasant there,” as she saw retrospectively all her former companions enjoying their freedom for at least a little space, as well as their wonted convivialities, and in her heart she longed to be with them. With this picture before her mind’s eye, she contrasted the quiet, peaceful life she was living with the excellent people of Wahkendall, and it seemed so dull and void of incident, that the very contrast served but to heighten her desire to return, that, at least, she might enjoy with them, once more, the coming festivities. These feelings had occupied a secret corner of her breast for some time, when, one morning, she told Mrs. Van Wagener that her old master Dumont would come that day, and that she should go home with him on his return. They expressed some surprise, and asked her where she obtained her information. She replied, that no one had told her, but she felt that he would come.

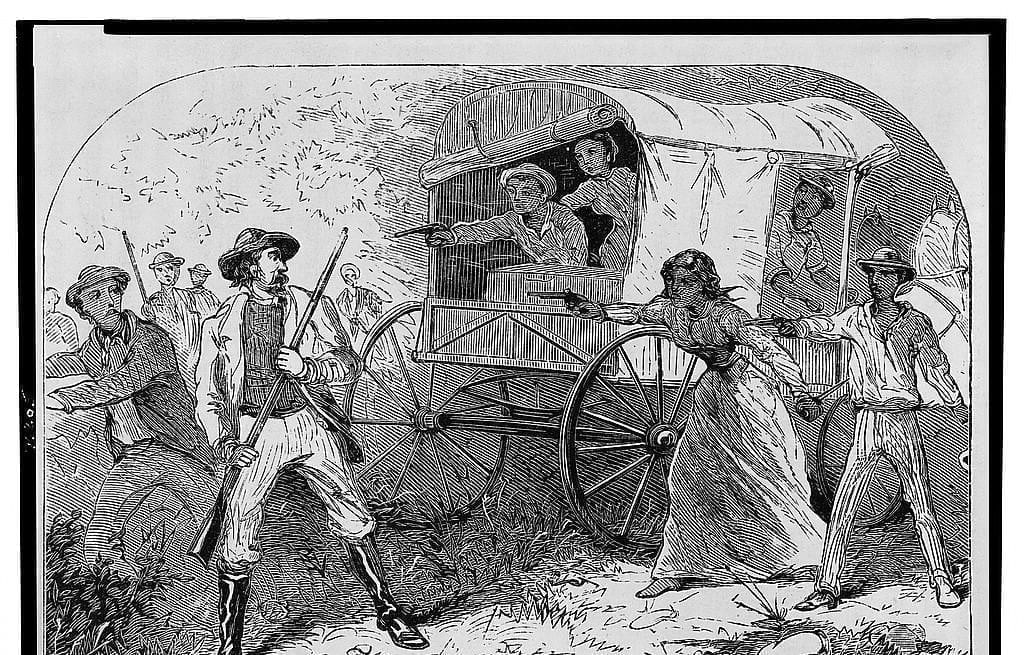

It seemed to have been one of those “events that cast their shadows before;” for, before night, Mr. Dumont made his appearance. She informed him of her intention to accompany him home. He answered, with a smile, “I shall not take you back again; you ran away from me.” Thinking his manner contradicted his words, she did not feel repulsed, but made herself and child ready; and when her former master had seated himself in the open dearborn,[3] she walked towards it, intending to place herself and child in the rear, and go with him. But, ere she reached the vehicle, she says that God revealed himself to her, with all the suddenness of a flash of lightning, showing her, “in the twinkling of an eye, that he was all over”—that he pervaded the universe—“and that there was no place where God was not.” She became instantly conscious of her great sin in forgetting her almighty Friend and “ever-present help in time of trouble.” All her unfulfilled promises arose before her, like a vexed sea whose waves run mountains high; and her soul, which seemed but one mass of lies, shrunk back aghast from the “awful look” of him whom she had formerly talked to, as if he had been a being like herself; and she would now fain have hid herself in the bowels of the earth, to have escaped his dread presence. But she plainly saw there was no place, not even in hell, where he was not; and where could she flee? . . .

A dire dread of annihilation now seized her, and she waited to see if, by “another look,” she was to be stricken from existence,—swallowed up, even as the fire licks up the oil with which it comes in contact.

When at last the second look came not, and her attention was once more called to outward things, she observed her master had left, and exclaiming aloud, “Oh, God, I did not know you were so big,” walked into the house, and made an effort to resume her work. But the workings of the inward man were too absorbing to admit of much attention to her avocations. She desired to talk to God, but her vileness utterly forbade it, and she was not able to prefer a petition. “What!” said she, “shall I lie again to God? I have told him nothing but lies; and shall I speak again, and tell another lie to God?” She could not; and now she began to wish for someone to speak to God for her. Then a space seemed opening between her and God, and she felt that if someone, who was worthy in the sight of heaven, would but plead for her in their own name, and not let God know it came from her, who was so unworthy, God might grant it. At length a friend appeared to stand between herself and an insulted Deity; and she felt as sensibly refreshed as when, on a hot day, an umbrella had been interposed between her scorching head and a burning sun. But who was this friend? became the next inquiry. . . .

“Who are you?” she exclaimed, as the vision brightened into a form distinct, beaming with the beauty of holiness, and radiant with love. She then said, audibly addressing the mysterious visitant—“I know you, and I don’t know you.” Meaning, “You seem perfectly familiar; I feel that you not only love me, but that you always have loved me—yet I know you not—I cannot call you by name.” When she said, “I know you,” the subject of the vision remained distinct and quiet. When she said, “I don’t know you,” it moved restlessly about, like agitated waters. So while she repeated, without intermission, “I know you, I know you,” that the vision might remain—”Who are you?” was the cry of her heart, and her whole soul was in one deep prayer that this heavenly personage might be revealed to her, and remain with her. At length, after bending both soul and body with the intensity of this desire, till breath and strength seemed failing, and she could maintain her position no longer, an answer came to her, saying distinctly, “It is Jesus.”

“Yes,” she responded, “it is Jesus.”

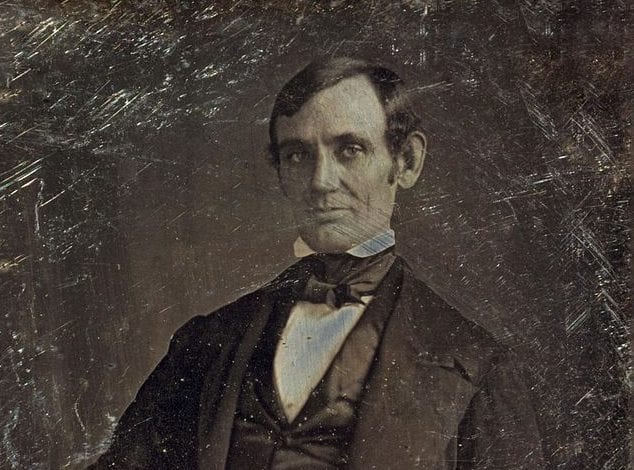

Previous to these exercises of mind, she heard Jesus mentioned in reading or speaking, but had received from what she heard no impression that he was any other than an eminent man, like a Washington or a Lafayette. Now he appeared to her delighted mental vision as so mild, so good, and so every way lovely, and he loved her so much! And, how strange that he had always loved her, and she had never known it! And how great a blessing he conferred, in that he should stand between her and God! And God was no longer a terror and a dread to her.

She stopped not to argue the point, even in her own mind, whether he had reconciled her to God, or God to herself, (though she thinks the former now,) being but too happy that God was no longer to her as a consuming fire, and Jesus was “altogether lovely.” Her heart was now full of joy and gladness, as it had been of terror, and at one time of despair. In the light of her great happiness, the world was clad in new beauty, the very air sparkled as with diamonds, and was redolent of heaven. . . .

- 1. Frederick Douglass (c. 1818–1895) was a self-emancipated slave who became an outspoken leader in the abolitionist movement.

- 2. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave in The Portable Frederick Douglass (New York: Penguin Press, 2016), 65.

- 3. a type of wagon

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.