By 1830, slavery had become very much a regional, as opposed to a national institution (see Number of Slaves in the Territory Enumerated, 1790 to 1850). The New England and Middle States had, through a combination of gradual abolition and immediate emancipation measures, dramatically decreased the number of slaves in their territories, while the Southern states had increased their reliance upon slave labor in the production of various cash crops, chief among them “King Cotton.” Nevertheless, there were individuals in both sections of the country who recognized the need for continued prudential reform. In December 1833, dozens of Northern activists met in Philadelphia to found the American Anti-Slavery Society. Although the group called for the immediate and uncompensated emancipation of all enslaved persons, they also denounced the use of violent resistance – an important concession to Southern slaveholders fearful of additional armed uprisings like Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831). Southern activist Angelina Grimke addressed similar fears in her Appeal to the Christian Women of the South. Grimke urged Southern women to speak out against slavery as an unjust and oppressive system, but also counseled them to encourage patience and submission on the part of their slaves until freedom was obtained.

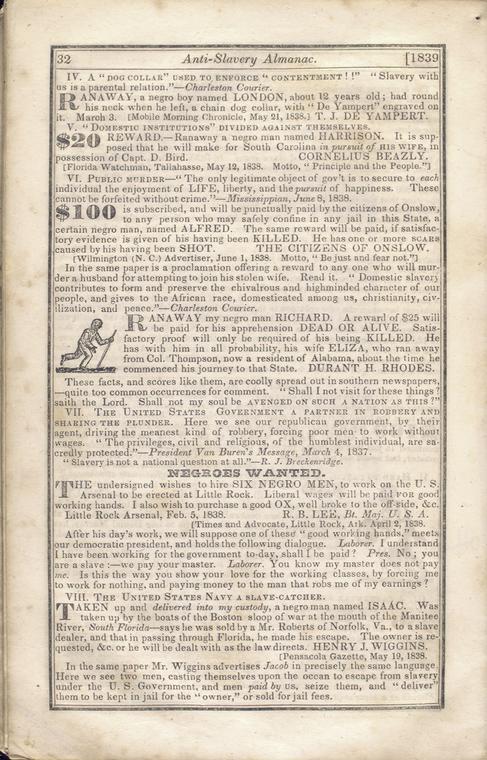

As the decade wore on, such moderate positions were eclipsed by a hardening of views and greater entrenchment on both sides. Southern newspapers carried advertisements for runaway slaves that described them in horrific, brutalizing terms, which Northern publishers delighted in reprinting to highlight the inhumanity of slaveholders. In 1849, Frederick Douglass – a self-emancipated former slave – emphatically denounced all plans related to abolition that did not also aim at ending racial prejudice and lead towards the formal equality of blacks and whites. Yet five years later, Southern sociologist George Fitzhugh was still defending race-based slavery as positive good, arguing that it benefited the slave as well as the owner.