Introduction

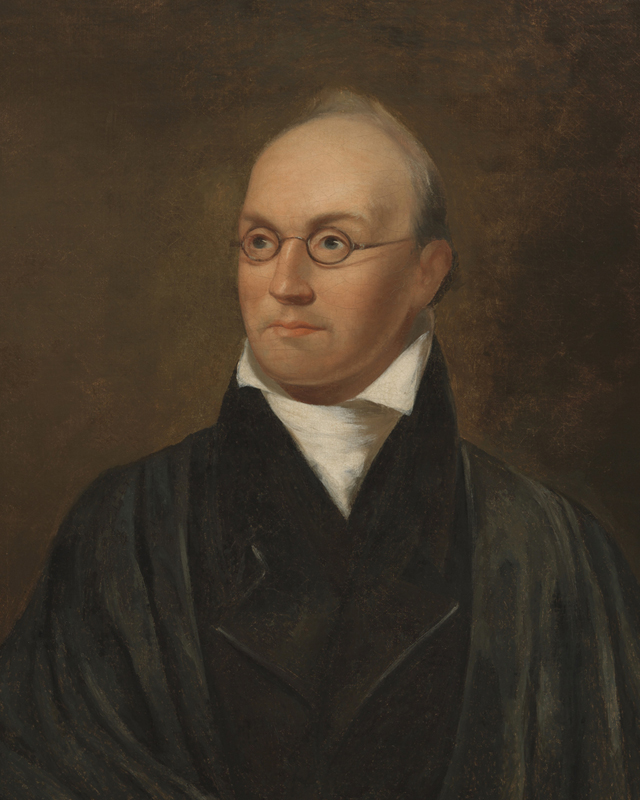

Joseph Story was an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and the first professor of law at Harvard University. His commentaries are considered second only to the Federalist Papers as an authoritative source on the Constitution. In this excerpt Story considered the Indians’ rights to their ancestral lands.

—Jace Weaver

§ 2. . . . . [Right of discovery] became the basis of European polity and regulated the exercise of the rights of sovereignty and settlement in all the cis-Atlantic1 plantations. In respect to desert and uninhabited lands, there does not seem any important objection which can be urged against it. But in respect to countries then inhabited by the natives, it is not easy to perceive how, in point of justice, or humanity, or general conformity to the law of nature, it can be successfully vindicated. As a conventional rule it might properly govern all the nations which recognized its obligation, but it could have no authority over the aborigines of America, whether gathered into civilized communities or scattered in hunting tribes over the wilderness. Their right, whatever it was, of occupation or use stood upon original principles deducible from the law of nature and could not be justly narrowed or extinguished without their own free consent.

§ 3. There is no doubt that the Indian tribes inhabiting this continent at the time of its discovery maintained a claim to the exclusive possession and occupancy of the territory within their respective limits, as sovereigns and absolute proprietors of the soil. They acknowledged no obedience, or allegiance, or subordination to any foreign sovereign whatsoever; and as far as they have possessed the means, they have ever since asserted this plenary2 right of dominion and yielded it up only when lost by the superior force of conquest or transferred by a voluntary cession.

§ 4. This is not the place to enter upon the discussion of the question of the actual merits of the titles claimed by the respective parties upon principles of natural law. That would involve the consideration of many nice and delicate topics as to the nature and origin of property in the soil and the extent to which civilized man may demand it from the savage for uses or cultivation different from, and perhaps more beneficial to, society than its uses to which the latter may choose to appropriate it. Such topics belong more properly to a treatise on natural law than to lectures professing to treat upon the law of a single nation.

§ 5. The European nations found little difficulty in reconciling themselves to the adoption of any principle which gave ample scope to their ambition and employed little reasoning to support it. They were content to take counsel of their interests, their prejudices, and their passions, and felt no necessity of vindicating their conduct before cabinets, which were already eager to recognize its justice and its policy. The Indians were a savage race, sunk in the depths of ignorance and heathenism. If they might not be extirpated for their want of religion and just morals, they might be reclaimed from their errors. They were bound to yield to the superior genius of Europe, and in exchanging their wild and debasing habits for civilization and Christianity they were deemed to gain more than an equivalent for every sacrifice and suffering. The Papal authority, too, was brought in aid of these great designs. . . .

§ 7. It may be asked, what was the effect of this principle of discovery in respect to the rights of the natives themselves. In the view of Europeans, it created a peculiar relation between themselves and the aboriginal inhabitants. The latter were admitted to possess a present right of occupancy, or use in the soil, which was subordinate to the ultimate dominion of the discoverer. They were admitted to be the rightful occupants of the soil, with a legal as well as just claim to retain possession of it, and to use it according to their own discretion. In a certain sense they were permitted to exercise rights of sovereignty over it. They might sell or transfer it to the sovereign, who discovered it; but they were denied the authority to dispose of it to any other persons, and until such a sale or transfer, they were generally permitted to occupy it as sovereigns de facto. But notwithstanding this occupancy, the European discoverers claimed and exercised the right to grant the soil while yet in possession of the natives, subject however to their right of occupancy; and the title so granted was universally admitted to convey a sufficient title in the soil to the grantees in perfect dominion, or, as it is sometimes expressed in treatises of public law, it was a transfer of plenum et utile dominium.3…