No related resources

Introduction

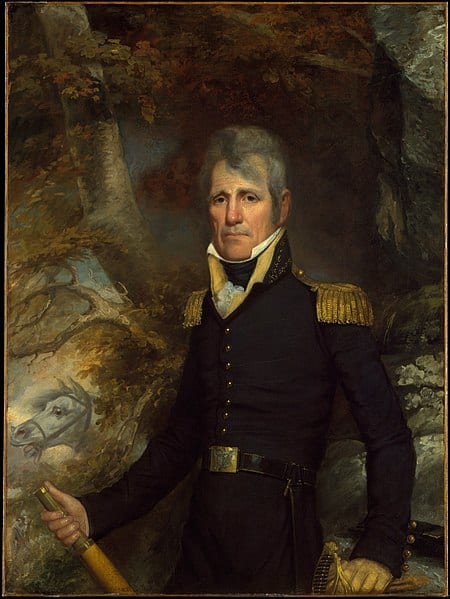

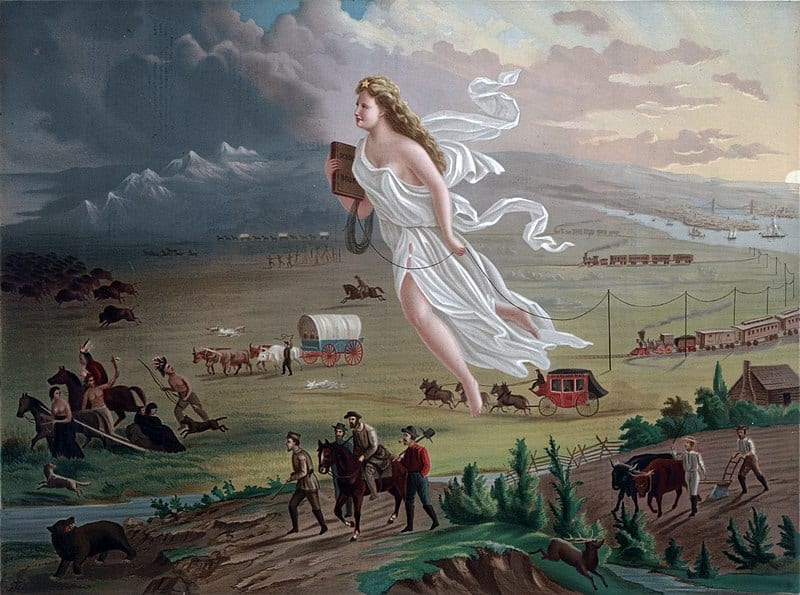

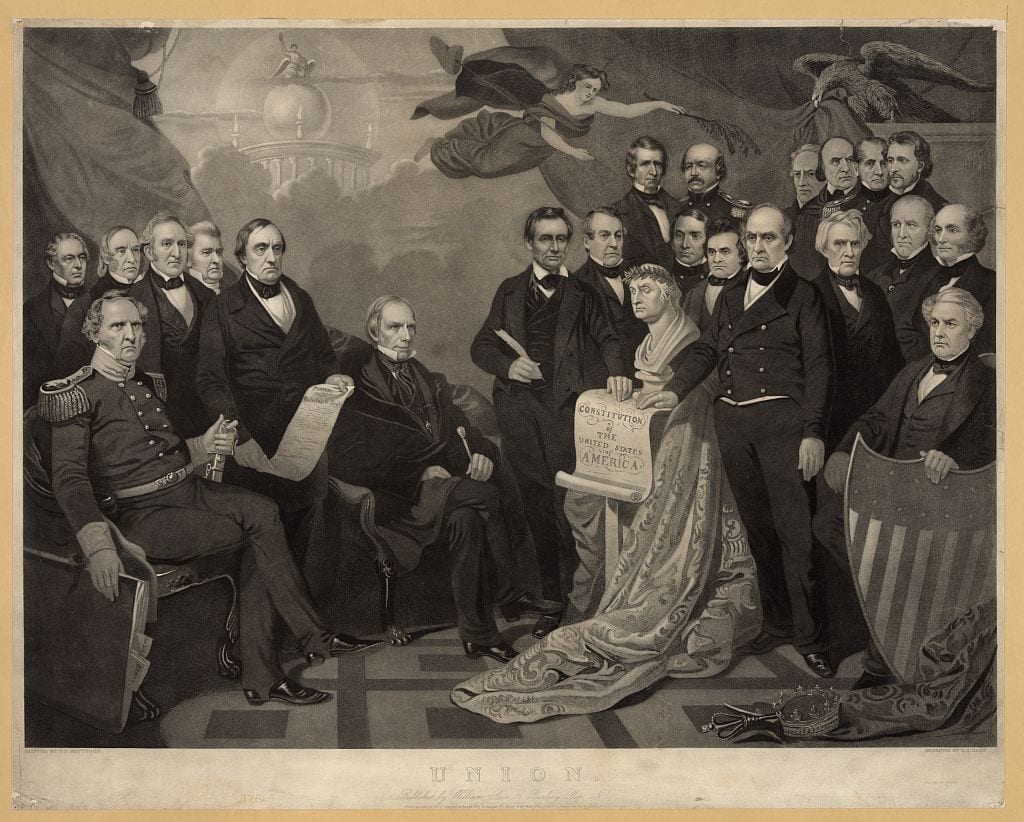

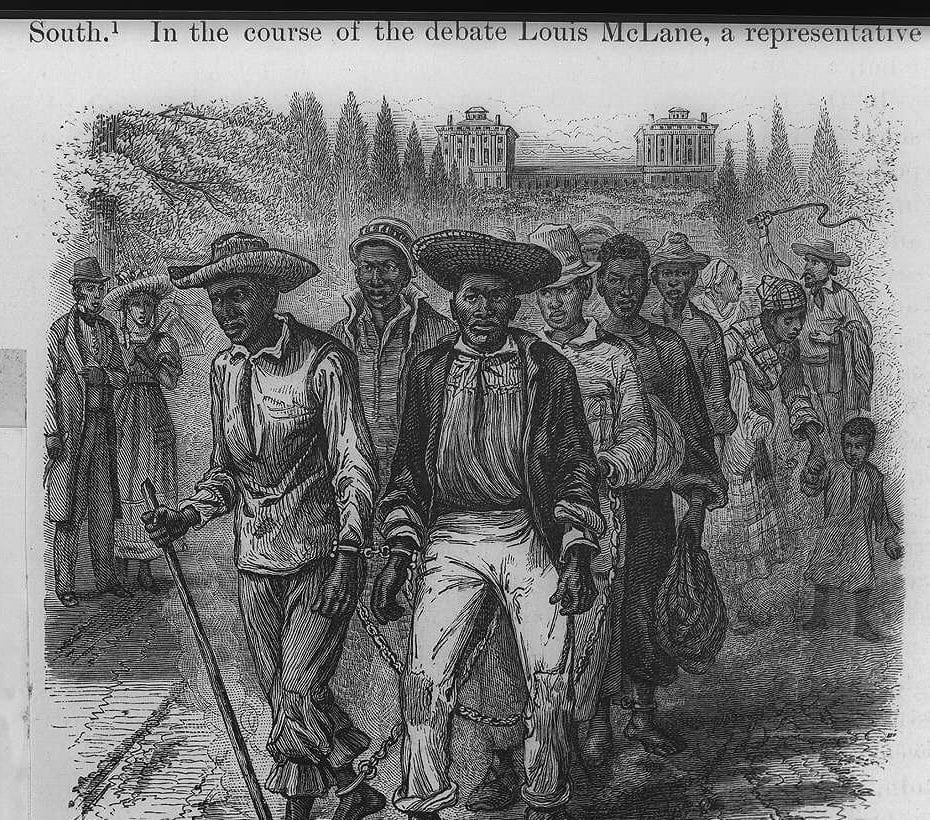

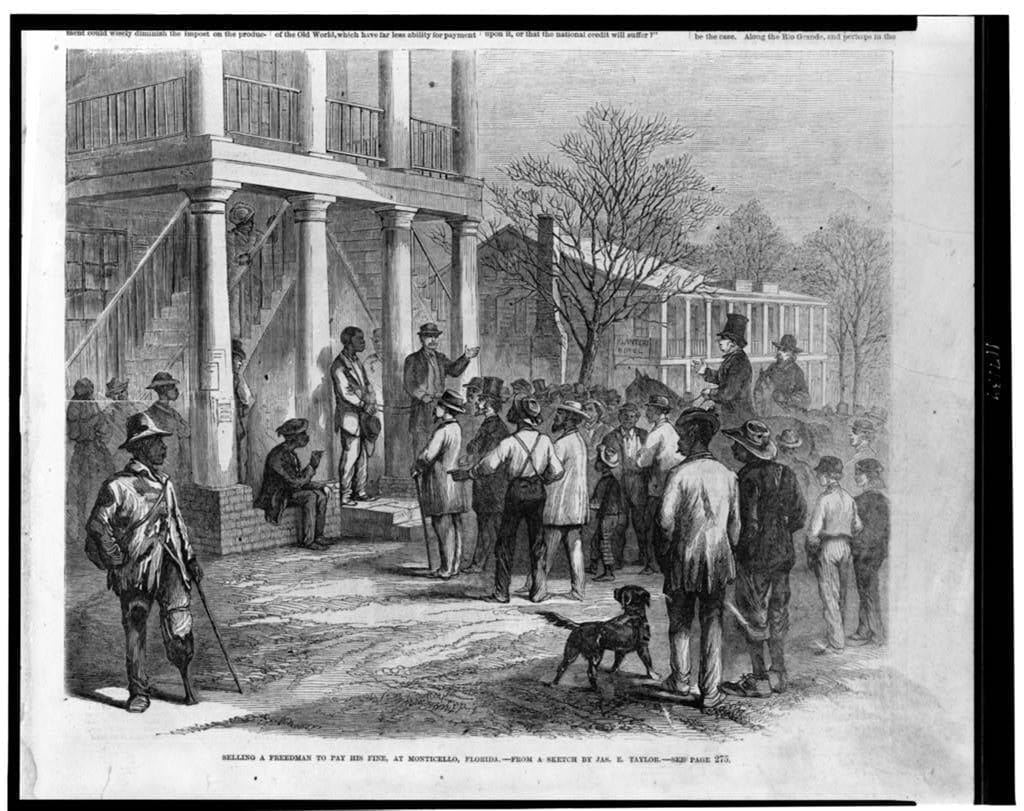

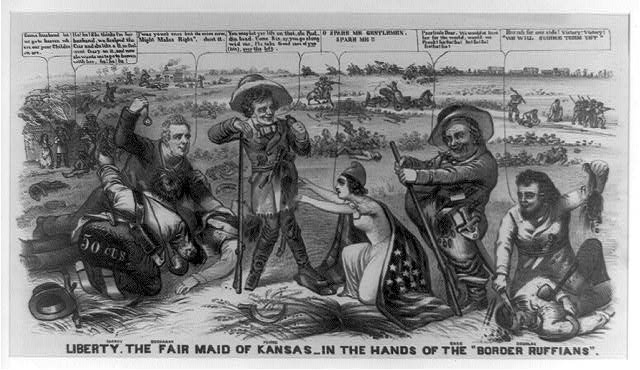

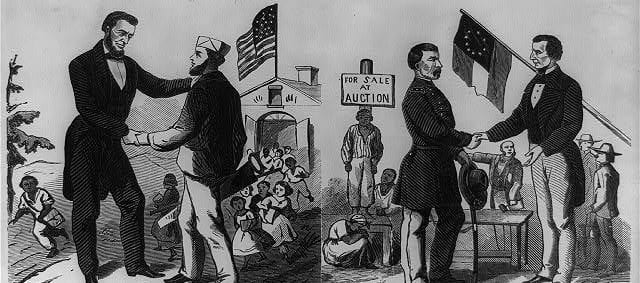

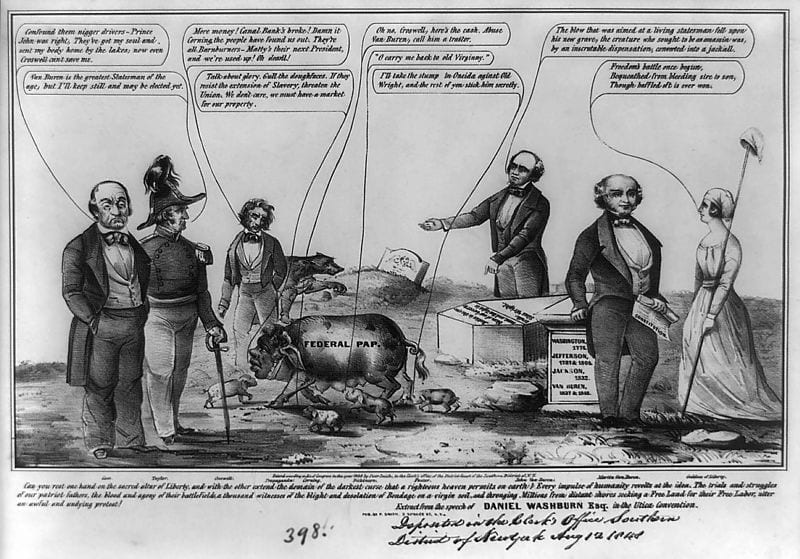

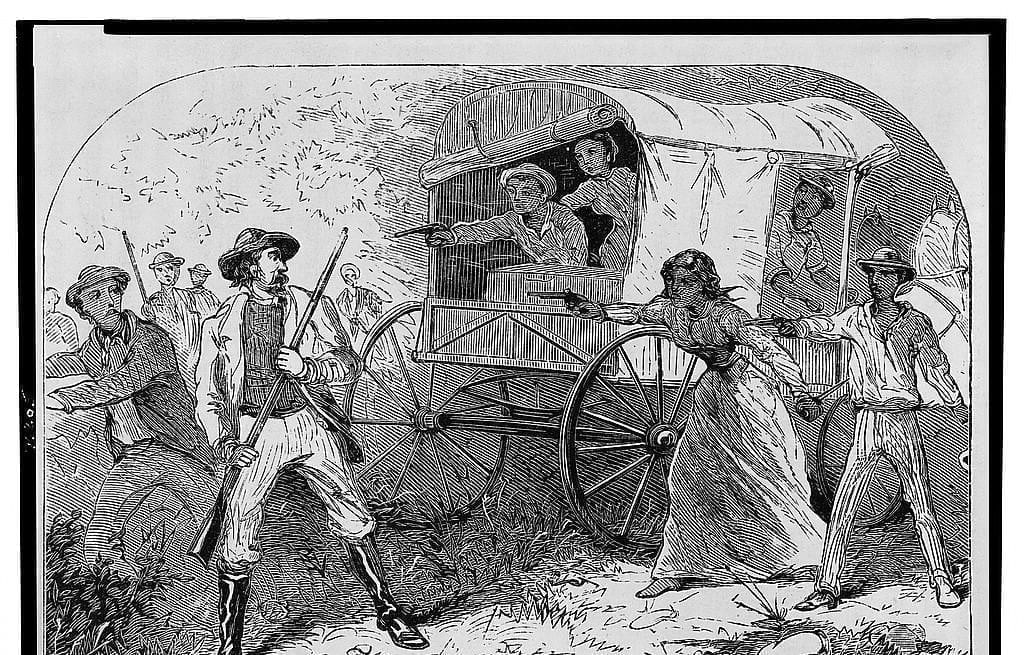

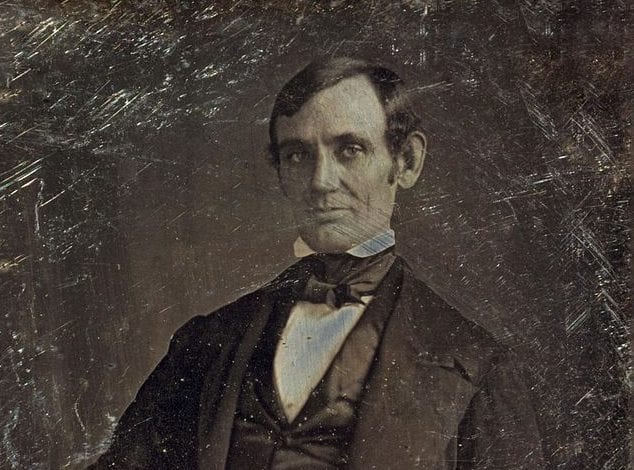

The passage of the Indian Removal Act during the administration of Andrew Jackson (1767–1845, See Veto of the Bank Bill) led eventually to the relocation of eastern Indians to the western territories (present-day Oklahoma). Some Indians sold their land and moved voluntarily; others resisted removal. Among the Cherokee, the majority committed to peaceful resistance to the pressure for removal, while a much smaller group reluctantly agreed to relocate. When the U.S. government negotiated a treaty with the Cherokee who agreed to relocate (the Treaty of New Echota, 1835), it took the treaty to apply to all Cherokee, even though the official leadership of the tribe did not accept it. Those Cherokee who did not voluntarily relocate were forcibly moved to the western territories.

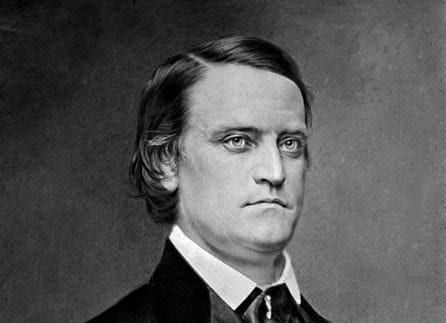

John Ross (1790–1866), an opponent of relocation, was the Cherokee chief throughout the struggle over removal and until his death years later. Ross’ mother was Cherokee, his father of Scottish descent. He was bilingual, which helped establish him as a negotiator with the federal government. A businessman, Ross became involved in Cherokee politics and joined the Cherokee General Council, which consisted largely of wealthier, educated Cherokee of mixed parentage like Ross. He was elected principal chief in 1828. Ross is credited with authorship of the 1830 address by the General Council against removal excerpted below. Written in response to the Jackson administration’s plans for a removal law, it recounted the pressure exerted by the state of Georgia against the Cherokee, explained why the federal government should protect the Cherokee from state action, and made an eloquent appeal for justice.

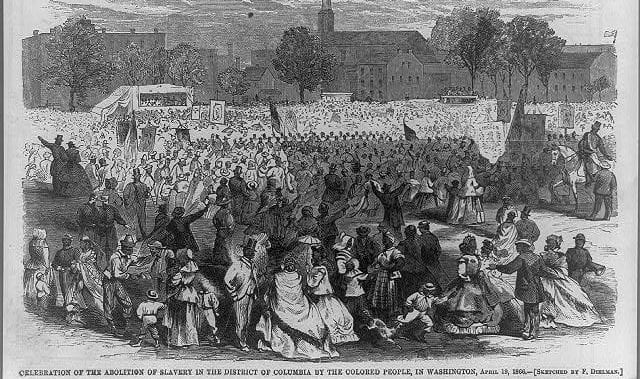

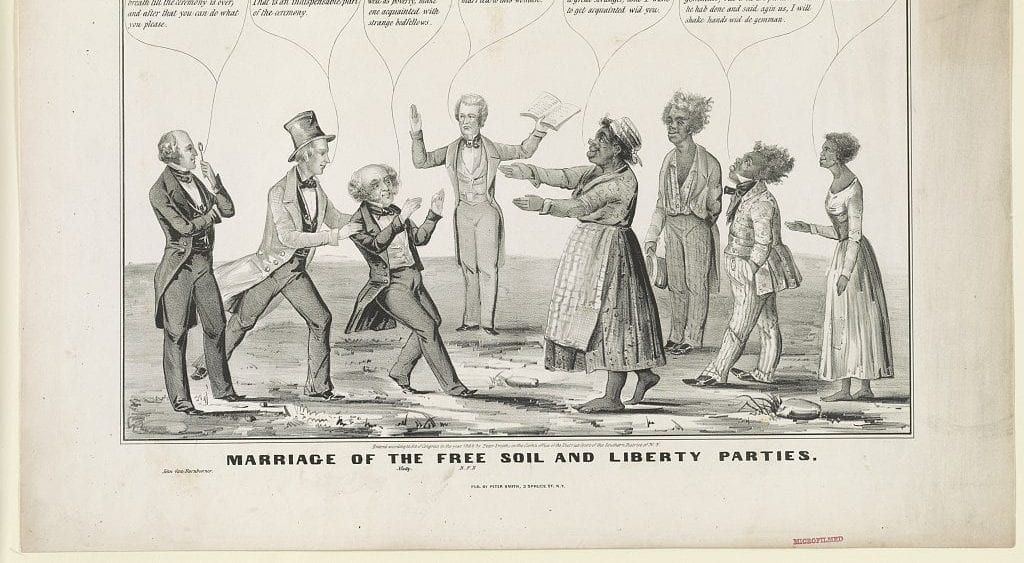

The appeal was unavailing. The Removal Act passed, despite the opposition of Christian missionaries to the Indians and their numerous supporters among what has been called the benevolent empire of reform-minded American Protestants (See The Nature, Importance, and Means of Eminent Holiness throughout the Church). Whig opponents of Jackson, including prominent politicians such as Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen (1787–1862) of New Jersey, also opposed the Removal Act. Ross and the majority of Cherokee continued to resist removal, despite the act and the Echota treaty. The hunger for Indian land was too great to resist, however, especially after the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in 1828. Pressure for land and disregard for the Indians led to forced removal and all the evils that Ross foretold in his address. An estimated two thousand to eight thousand Cherokee died on the “Trail of Tears” to the west. The Creeks and Chickasaw were dispossessed in Alabama and Mississippi in a process similar to what occurred in Georgia, and with an equal, if not greater, loss of life.

Source: E. C. Tracy, Memoir of the Life of Jeremiah Evarts, Late Corresponding Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1845), 442–448, available at https://books.google.com.

Some months ago a delegation was appointed by the constituted authorities of the Cherokee Nation, to repair to the city of Washington, and, in behalf of this Nation to lay before the government of the United States such representations as should seem most likely to secure to us as a people that protection, aid, and good neighborhood which had been so often promised to us, and of which we stand in great need. Soon after their arrival in the city they presented to Congress a petition from our National [General] Council, asking for the interposition of that body in our behalf, especially with reference to the laws of Georgia, which were suspended in a most terrifying manner over a large part of our population, and protesting in the most decided terms against the operation of these laws. In the course of the winter they presented petitions to Congress. . . pleading with the assembled representatives of the American people, that the solemn engagements between their fathers and our fathers may be preserved, as they have been till recently in full force and continued operation. . . .

More than a year ago we were officially given to understand by the secretary of war that the president could not protect us against the laws of Georgia.1 This information was entirely unexpected; as it went upon the principle that treaties made between the United States and the Cherokee Nation have no power to withstand the legislation of separate states; and of course that they have no efficacy whatever, but leave our people to the mercy of the neighboring whites, whose supposed interests would be promoted by our expulsion or extermination. It would be impossible to describe the sorrow which affected our minds on learning that the chief magistrate of the United States2 had come to this conclusion, that all his illustrious predecessors had held intercourse with us on principles which could not be sustained; that they had made promises of vital importance to us, which could not be fulfilled—promises made hundreds of times, in almost every conceivable manner—often in the form of solemn treaties. . . .

Soon after the War of the Revolution, as we have learned from our fathers, the Cherokees looked upon the promises of the whites with great distrust and suspicion; but the frank and magnanimous conduct of General Washington did much to allay these feelings. The perseverance of successive presidents, and especially of Mr. Jefferson in the same course of policy, and in the constant assurance that our country should remain inviolate, except so far as we voluntarily ceded it, nearly perished anxiety in regard to encroachments from the whites. To this result the aid which we received from the United States in the attempts of our people to become civilized, and the kind efforts of benevolent societies have greatly contributed.3 Of late years, however, much solicitude was occasioned among our people by the claims of Georgia. This solicitude arose from an apprehension that by extreme importunity, threats, and other undue influence, a treaty would be made, which should cede the territory and thus compel the inhabitants to remove.4 But it never occurred to us for a moment that without any new treaty, without any assent of our rulers and people, without even a pretended compact, and against our vehement and unanimous protestations, we should be delivered over to the discretion of those who had declared by a legislative act that they wanted the Cherokee lands and would have them.5

Finding that relief could not be obtained from the chief magistrate, and not doubting that our claim to protection was just, we made our application to Congress. During four long months our delegation waited at the doors of the national legislature of the United States, and the people at home, in the most painful suspense, to learn in what manner our application would be answered; and now that Congress has adjourned, on the very day before the date fixed by Georgia for the extension of her oppressive laws over the greater part of our country, the distressing intelligence has been received that we have received no answer at all; and no department of the government has assured us that we are to receive the desired protection. But just at the close of the session, an act was passed by which half a million of dollars was appropriated toward effecting a removal of Indians;6 and we have great reason to fear that the influence of this act will be brought to bear most injuriously upon us. The passage of this act is certainly understood by the representatives of Georgia as abandoning us to the oppressive and cruel measures of the state, and is sustaining the opinion that treaties with Indians do not restrain state legislation. . . .To our countrymen, this has been melancholy intelligence, and with the most bitter disappointment has it been received.

But in the midst of our sorrows, we do not forget our obligations to our friends and benefactors. It was with sensations of inexpressionable joy that we have learned that the voice of thousands in many parts of the United States has been raised in our behalf, and the numerous memorials offered in our favor, in both houses of Congress. . . .Our special thanks are due however, to those honorable men, who so ably and eloquently asserted our rights, in both branches of the national legislature. . . .

Before we close this address, permit us to state what we conceive to be our relations with the United States. After the peace of 1785,7 the Cherokees were an independent people; absolutely so, so much as any people on earth. They had been allies to Great Britain, and as a faithful ally, took a part in the colonial war on her side.8. . . She [Great Britain] acknowledged the independence of the United States and made peace. The Cherokees therefore stood alone; and in these circumstances continued the war. They were then under no obligations to the United States any more than to Great Britain, France, or Spain. The United States never subjugated the Cherokees; on the contrary, our fathers remained in possession of their country, and with arms in their hands.

The people of the United States sought a peace; and, in 1785, the Treaty of Hopewell was formed, by which the Cherokees came under the protection of the United States and submitted to such limitation of sovereignty as are mentioned in that instrument. None of these limitations however, effected in the slightest degree their rights of self-government and inviolate territory.

. . . When the federal Constitution was adopted the Treaty of Hopewell was contained, with all other treaties, as the supreme law of the land. In 1791, the Treaty of Holston was made, by which the sovereignty of the Cherokees was qualified as follows: The Cherokees acknowledged themselves to be under the protection of the United States, and of no other sovereign. They engaged that they would not hold any treaty with a foreign power, with any separate state of the Union, or with individuals. They agreed that the United States should have the exclusive right of regulating their trade; that the citizens of the United States have a right of way in one direction through the Cherokee country; and that if an Indian should do injury to a citizen of the United States, he should be delivered up to be tried and punished. A cession of lands was also made to the United States. On the other hand, the United States paid a sum of money; offered protection; engaged to punish citizens of the United States who should do any injury to the Cherokees; abandoned white settlers on Cherokee lands to the discretion of the Cherokees, stipulated that white men should not hunt on these lands, nor even enter the country without a passport; and gave a solemn guaranty of all Cherokees lands not ceded. This treaty is the basis of all subsequent compacts; and in none of them are the relations of the parties at all changed.

The Cherokees have always fulfilled their engagements. . . .

The people of the United States will have the fairness to reflect that all the treaties between them and the Cherokees were made at the sole invitation and for the benefit of the whites; that valuable considerations were given for every stipulation, on the part of the United States; that it is impossible to reinstate the parties in their former situation; that there are now hundreds of thousands of citizens of the United States residing upon lands ceded by the Cherokees in these very treaties, and that our people have trusted their country to the guaranty of the United States. If this guaranty fails them, in what can they trust, and where can they look for protection?

We are aware that some persons suppose it will be for our advantage to remove beyond the Mississippi. We think otherwise. Our people universally think otherwise. Thinking that it would be fatal to their interests, they have almost to a man sent their memorial to Congress, deprecating the necessity of a removal. . . .It is incredible that Georgia should ever have enacted the oppressive laws, to which reference is here made, unless she had supposed that something extremely terrific in its character was necessary in order to make the Cherokees willing to remove. We are not willing to remove; and if we could be brought to this extremity, it would be not by argument, not because our judgment was satisfied, not because our condition will be improved; but only because we cannot endure to be deprived of our national and individual rights and subjected to a process of intolerable oppression.

We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to claim without interruption or molestation. The treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursuance of treaties, guaranty our residence, and our privileges and secure us against intruders. Our only request is that these treaties may be fulfilled, and these laws executed.

But if we are compelled to leave our country, we see nothing but ruin before us. The country west of the Arkansas territory9 is unknown to us. From what we can learn of it, we have no prepossessions in its favor. All the inviting parts of it, as we believe, are preoccupied by various Indian nations, to which it has become assigned. They would regard us as intruders and look upon us with an evil eye. The far greater part of that region is, beyond all controversy, badly supplied with wood and water; and no Indian tribe can live as agriculturists without these articles. All our neighbors in case of our removal, though crowded into our near vicinity, would speak a language totally different from ours and practice different customs. The original possessors of that region are now wandering savages, lurking for prey in the neighborhood. They have always been at war, and would be easily tempted to turn their arms against peaceful emigrants. Were the country to which we are urged much better than it is represented to be, and were it free from objections which we have made to it, still it is not the land of our birth, nor of our affections. It contains neither the scenes of our childhood, nor the graves of our fathers. . . .

It is under a sense of the most pungent feelings that we make this, perhaps our last appeal to the good people of the United States. . . . Shall we be compelled by a civilized and Christian people, with whom we have lived in perfect peace for the last forty years, and for whom we have willingly bled in war,10 to bid a final adieu to our homes, our farms, our streams, and our beautiful forests? No. We are still firm. We intend still to cling with our wonted affection to the land which gave us birth and which every day of our lives brings to us new and stronger ties of attachment. . . . On the soil which contains the ashes of our beloved men we wish to live—on this soil we wish to die.

We entreat those to whom the preceding paragraphs are addressed to remember the great law of love, “Do to others as ye would that others should do to you.”11 Let them remember that of all nations on the earth, they are under the greatest obligations to obey this law. We pray them to remember that, for the sake of principle, their forefathers were compelled to leave, therefore driven from the old world, and that the winds of persecution wafted them over the great waters and landed them on the shores of the new world, when the Indian was the sole lord and proprietor of these extensive domains. Let them remember in what way they were received by the savage of America, when power was in his hand, and his ferocity could not be restrained by any human arm. We urge them to bear in mind that those who would now ask of them a cup of cold water, and a spot of earth, a portion of their own patrimonial possessions on which to live and die in peace, are the descendants of those, whose origin as inhabitants of North America history and tradition are alike insufficient to reveal. Let them bring to remembrance all these facts, and they cannot, and we are sure they will not, fail to remember and sympathize with us in these our trials and sufferings.

- 1. The state of Georgia passed a law extending its jurisdiction over Native Americans to take effect July 1, 1830.

- 2. The president of the United States, in this case Andrew Jackson.

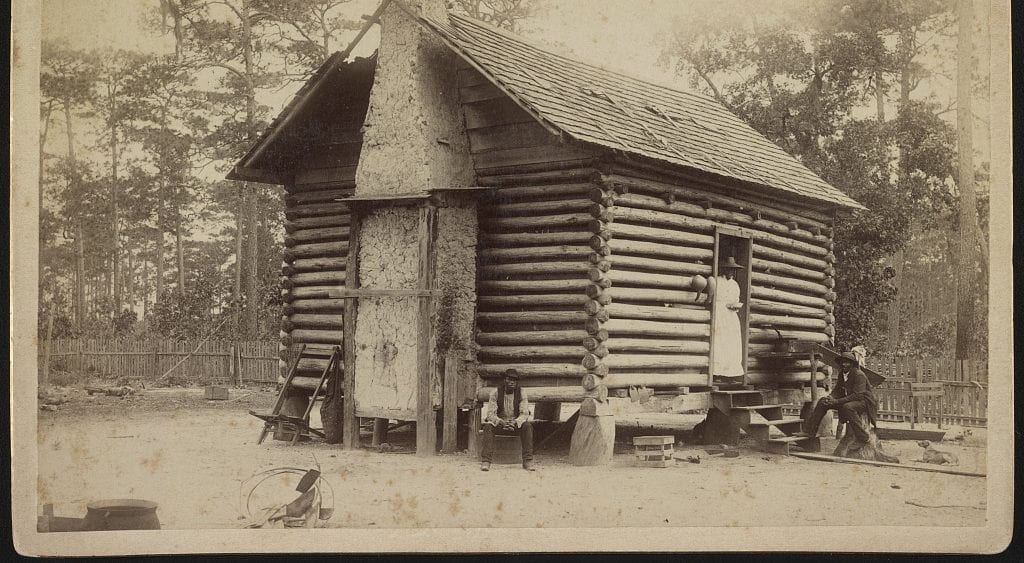

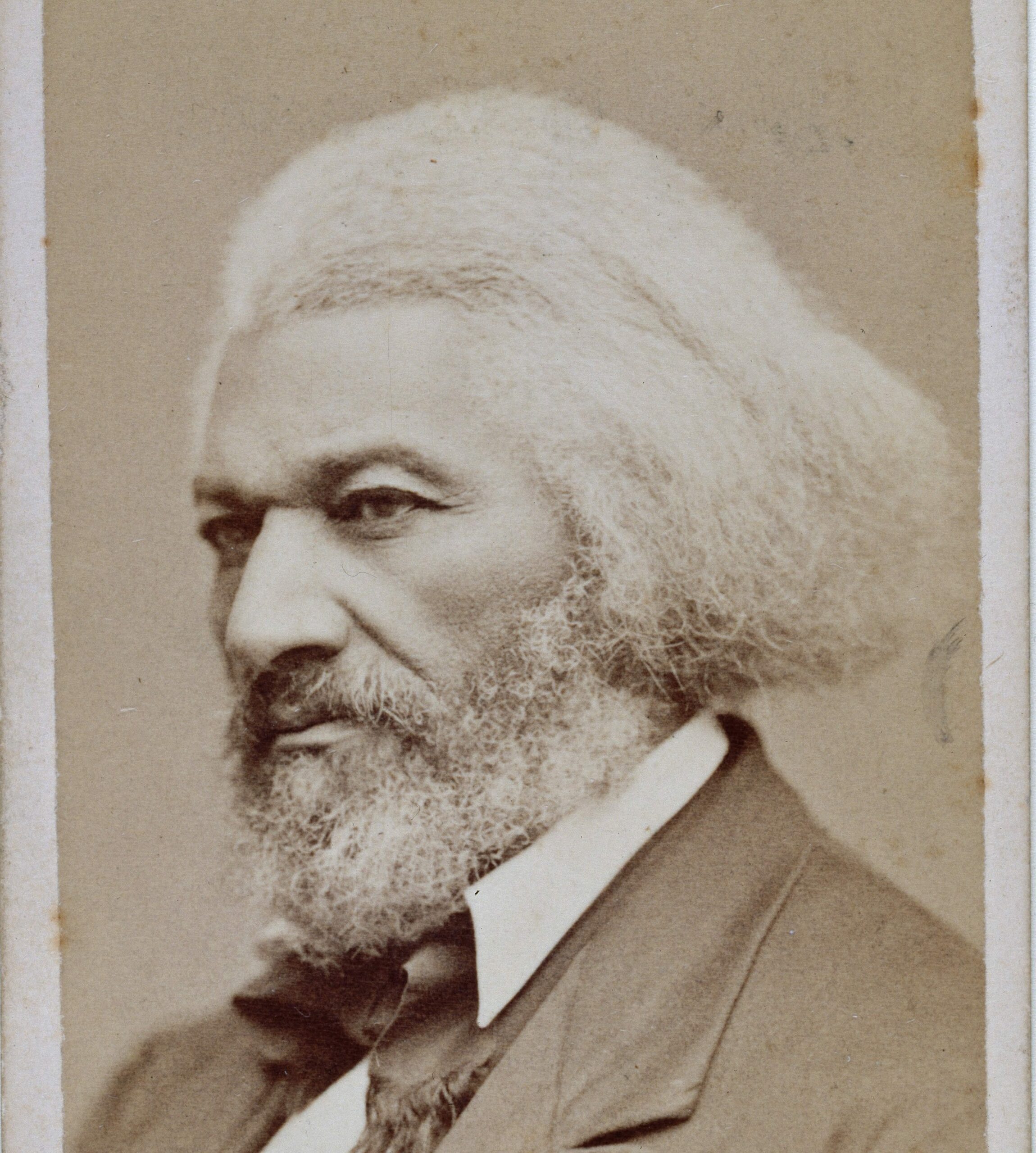

- 3. The Cherokee, Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles were referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes. They were agricultural, had centralized government, owned land as individuals, engaged in commerce, and intermarried with other Americans. Many were Christians. Like other southerners, some ran plantations and owned African Americans as slaves. Many became Christian through the missionary activity of American Protestants, whose benevolent or aid societies retained an interest in the tribes and tried to help them in their political struggles with the states and the federal government. See Document 15.

- 4. Ross foretold what came to pass in the Treaty of Echota.

- 5. Ross referred to the state of Georgia.

- 6. The Indian Removal Act of 1830.

- 7. The Treaty of Hopewell, mentioned below in Ross’ text.

- 8. The American Revolution.

- 9. What is today the state of Oklahoma.

- 10. The Cherokee had fought on behalf of the United States, including under Jackson’s command during his campaigns against other Indians.

- 11. Matthew 7:12; Luke 6:31.

Letter from James Madison to Edward Everett

August 28, 1830

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.