No related resources

Introduction

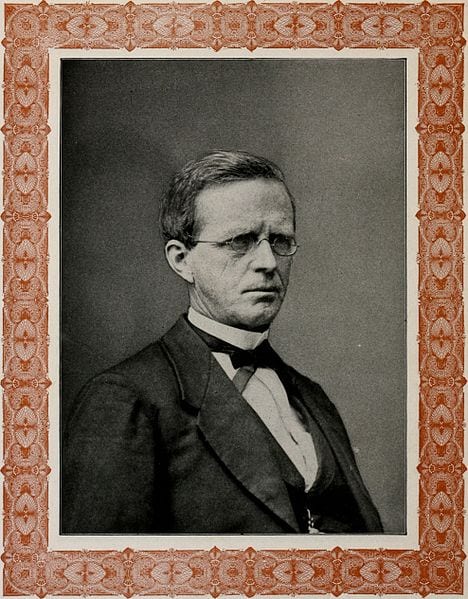

Presidents in the nineteenth century routinely vetoed bills on the grounds that they exceeded Congress’ enumerated powers. Many of the vetoes blocked internal improvement bills that funded construction or improvement of roads, canals, rivers, and harbors, but presidents also wielded the veto pen against other legislation they deemed to exercise powers not authorized by the Constitution. In 1859 President James Buchanan (1791–1868) vetoed a bill supporting land grant colleges. The bill, sponsored by Representative Justin Smith Morrill (R-VT; 1810–1898), would have donated public lands to states to support colleges offering instruction in the agricultural and mechanical arts. President Buchanan vetoed the bill on the grounds that it was inexpedient and unconstitutional. He argued that donating federal lands to states to support colleges would have harmful effects on relations between the federal and state governments. He also viewed the act as unconstitutional because he thought Congress did not have the power to expend money raised by taxing all the people “for the purpose of educating the people of the respective states.”

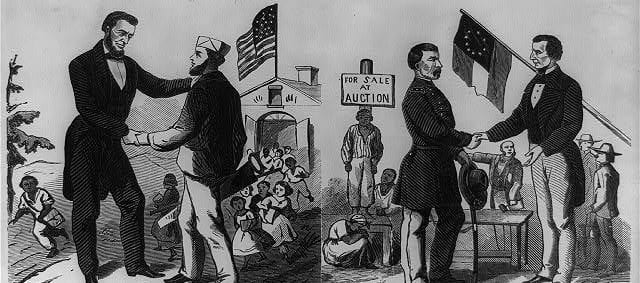

Several years later, during the Civil War, Congress reenacted a revised version of the act, once again sponsored by Representative Morrill and therefore referred to as the Morrill Act. President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law in 1862.

Source: James Buchanan, Veto Message, Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203065.

I return with my objections to the House of Representatives, in which it originated, the bill entitled “An act donating public lands to the several States and Territories which may provide colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the mechanic arts,” presented to me on the 18th instant.

This bill makes a donation to the several states of 20,000 acres of the public lands for each senator and representative in the present Congress, and also an additional donation of 20,000 acres for each additional representative to which any state may be entitled under the census of 1860.

According to a report from the Interior Department, based upon the present number of senators and representatives, the lands given to the states amount to 6,060,000 acres, and their value, at the minimum government price of $1.25 per acre, to $7,575,000.

The object of this gift, as stated by the bill, is “the endowment, support, and maintenance of at least one college (in each state) where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific or classical studies, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, as the legislatures of the states may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”...

I shall now proceed to state my objections to this bill. I deem it to be both inexpedient and unconstitutional.

1. This bill has been passed at a period when we can with great difficulty raise sufficient revenue to sustain the expenses of the government. Should it become a law the Treasury will be deprived of the whole, or nearly the whole, of our income from the sale of public lands, which for the next fiscal year has been estimated at $5,000,000....

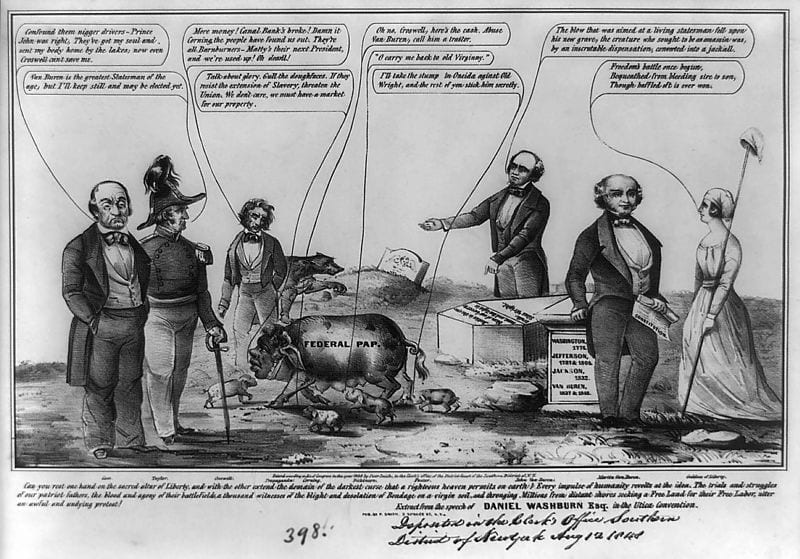

2. Waiving for the present the question of constitutional power, what effect will this bill have on the relations established between the federal and state governments? The Constitution is a grant to Congress of a few enumerated but most important powers, relating chiefly to war, peace, foreign and domestic commerce, negotiation, and other subjects which can be best or alone exercised beneficially by the common government. All other powers are reserved to the states and to the people. For the efficient and harmonious working of both, it is necessary that their several spheres of action should be kept distinct from each other. This alone can prevent conflict and mutual injury. Should the time ever arrive when the state governments shall look to the federal Treasury for the means of supporting themselves and maintaining their systems of education and internal policy, the character of both governments will be greatly deteriorated. The representatives of the states and of the people, feeling a more immediate interest in obtaining money to lighten the burdens of their constituents than for the promotion of the more distant objects entrusted to the federal government, will naturally incline to obtain means from the federal government for state purposes. If a question shall arise between an appropriation of land or money to carry into effect the objects of the federal government and those of the states, their feelings will be enlisted in favor of the latter. This is human nature; and hence the necessity of keeping the two governments entirely distinct....

6. But does Congress possess the power under the Constitution to make a donation of public lands to the different states of the Union to provide colleges for the purpose of educating their own people?

I presume the general proposition is undeniable that Congress does not possess the power to appropriate money in the Treasury, raised by taxes on the people of the United States, for the purpose of educating the people of the respective states. It will not be pretended that any such power is to be found among the specific powers granted to Congress nor that “it is necessary and proper for carrying into execution”1 any one of these powers. Should Congress exercise such a power, this would be to break down the barriers which have been so carefully constructed in the Constitution to separate federal from state authority. We should then not only “lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises”2 for federal purposes, but for every state purpose which Congress might deem expedient or useful. This would be an actual consolidation of the federal and state governments so far as the great taxing and money power is concerned, and constitute a sort of partnership between the two in the Treasury of the United States, equally ruinous to both.

But it is contended that the public lands are placed upon a different footing from money raised by taxation and that the proceeds arising from their sale are not subject to the limitations of the Constitution, but may be appropriated or given away by Congress, at its own discretion, to states, corporations, or individuals for any purpose they may deem expedient.

The advocates of this bill attempt to sustain their position upon the language of the second clause of the third section of the fourth article of the Constitution, which declares that “the Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States.” They contend that by a fair interpretation of the words “dispose of” in this clause Congress possesses the power to make this gift of public lands to the states for purposes of education.

It would require clear and strong evidence to induce the belief that the framers of the Constitution, after having limited the powers of Congress to certain precise and specific objects, intended by employing the words “dispose of” to give that body unlimited power over the vast public domain. It would be a strange anomaly, indeed, to have created two funds—the one by taxation, confined to the execution of the enumerated powers delegated to Congress, and the other from the public lands, applicable to all subjects, foreign and domestic, which Congress might designate; that this fund should be “disposed of,” not to pay the debts of the United States, nor “to raise and support armies,” nor “to provide and maintain a navy,” nor to accomplish any one of the other great objects enumerated in the Constitution, but be diverted from them to pay the debts of the states, to educate their people, and to carry into effect any other measure of their domestic policy. This would be to confer upon Congress a vast and irresponsible authority, utterly at war with the well-known jealousy of federal power which prevailed at the formation of the Constitution. The natural intendment would be that as the Constitution confined Congress to well-defined specific powers, the funds placed at their command, whether in land or money, should be appropriated to the performance of the duties corresponding with these powers. If not, a government has been created with all its other powers carefully limited, but without any limitation in respect to the public lands....

It has been asserted truly that Congress in numerous instances have granted lands for the purposes of education. These grants have been chiefly, if not exclusively, made to the new states as they successively entered the Union, and consisted at the first of one section and afterward of two sections of the public land in each township for the use of schools, as well as of additional sections for a state university. Such grants are not, in my opinion, a violation of the Constitution. The United States is a great landed proprietor, and from the very nature of this relation it is both the right and the duty of Congress as their trustee to manage these lands as any other prudent proprietor would manage them for his own best advantage. Now no consideration could be presented of a stronger character to induce the American people to brave the difficulties and hardships of frontier life and to settle upon these lands and to purchase them at a fair price than to give to them and to their children an assurance of the means of education. If any prudent individual had held these lands, he could not have adopted a wiser course to bring them into market and enhance their value than to give a portion of them for purposes of education. As a mere speculation he would pursue this course. No person will contend that donations of land to all the states of the Union for the erection of colleges within the limits of each can be embraced by this principle. It cannot be pretended that an agricultural college in New York or Virginia would aid the settlement or facilitate the sale of public lands in Minnesota or California. This cannot possibly be embraced within the authority which a prudent proprietor of land would exercise over his own possessions. I purposely avoid any attempt to define what portions of land may be granted, and for what purposes, to improve the value and promote the settlement and sale of the remainder without violating the Constitution. In this case I adopt the rule that “sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.”3

African Civilization Society

February, 1859

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.