No related resources

Introduction

As the United States celebrated the centennial of its independence, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that had serious implications for continued presidential control over clandestine operations. Most Americans were unaware of the extent to which their presidents had used secret operations as a tool of American foreign policy in both peacetime and wartime. This decision, for better or worse, upheld that tradition.

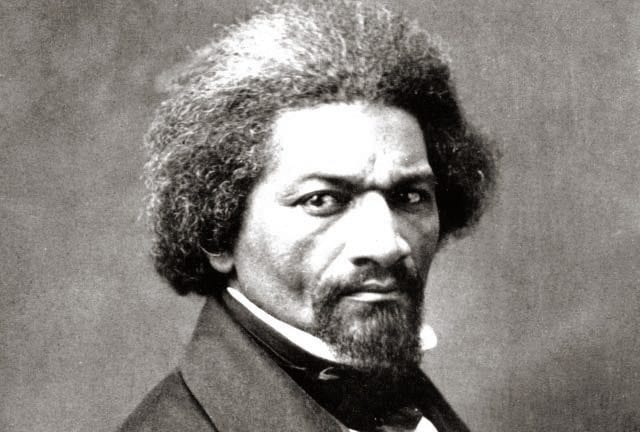

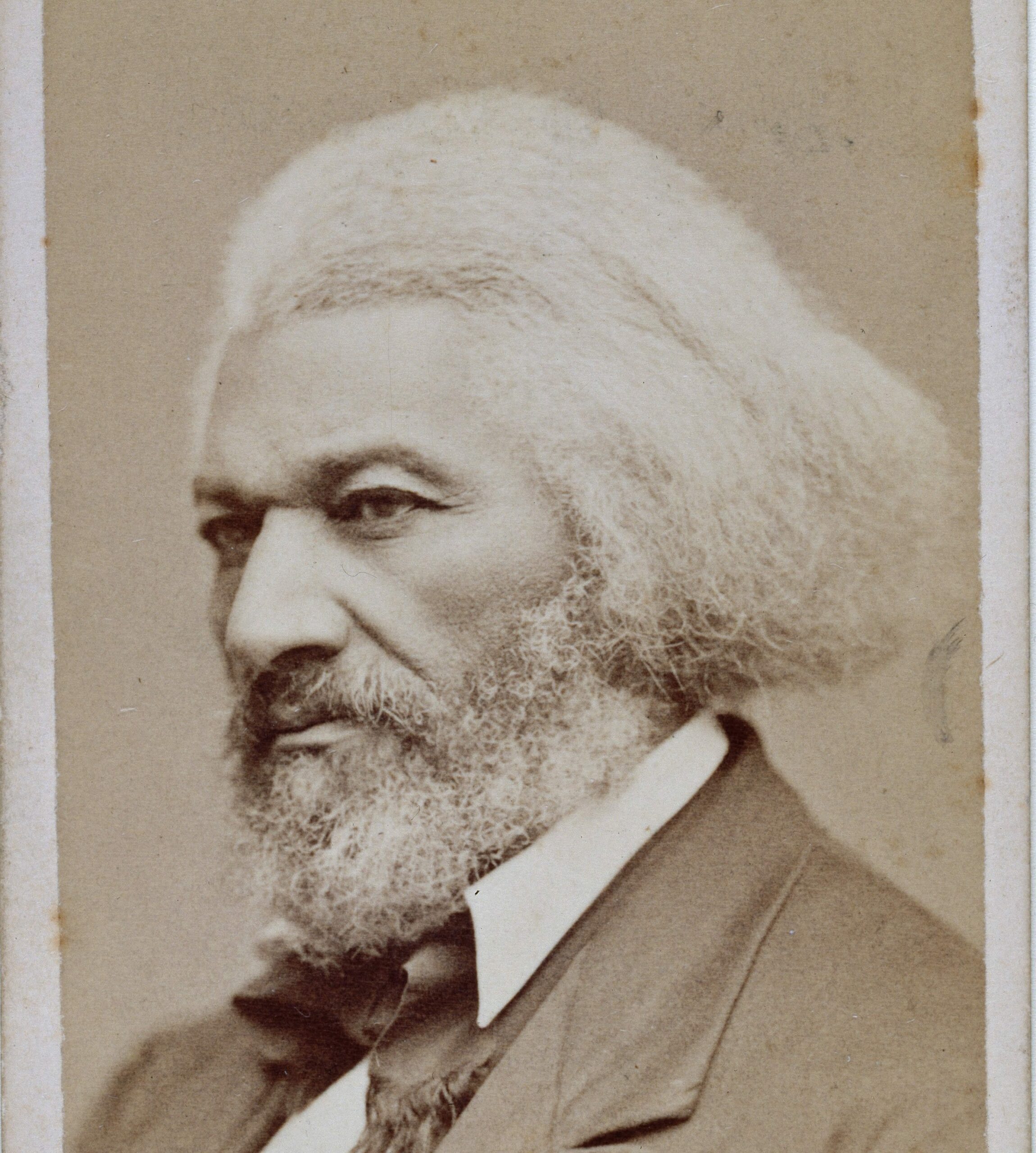

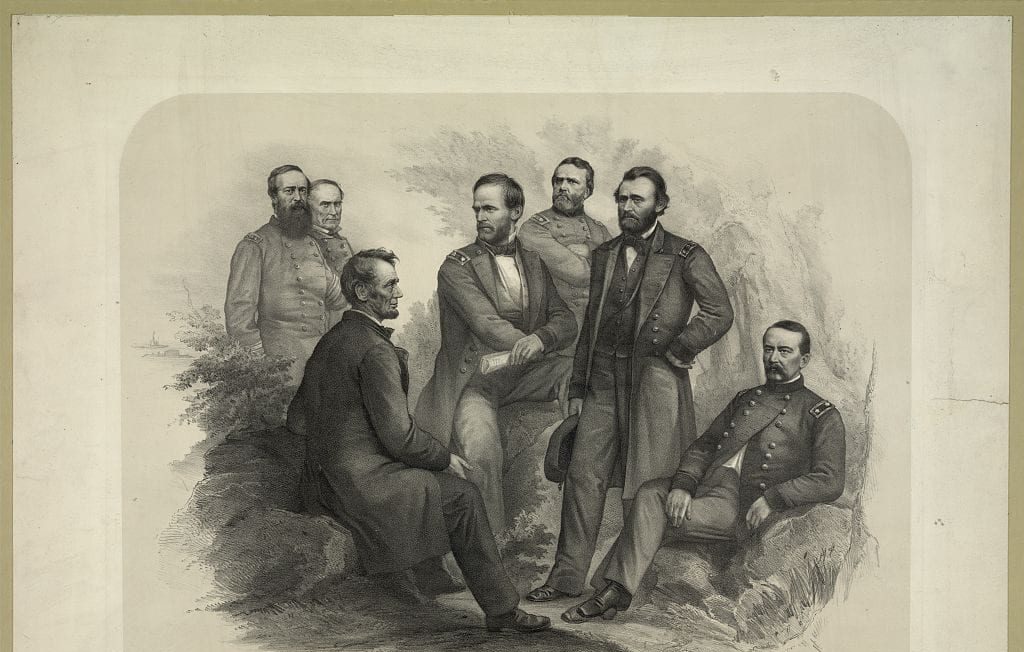

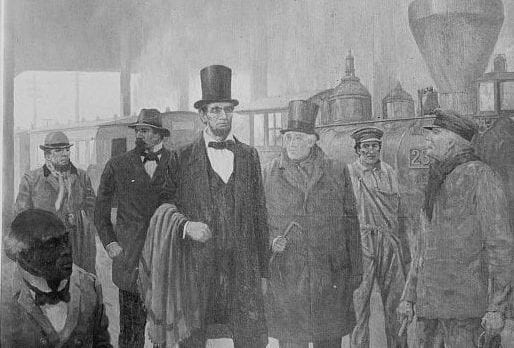

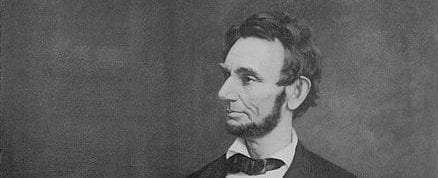

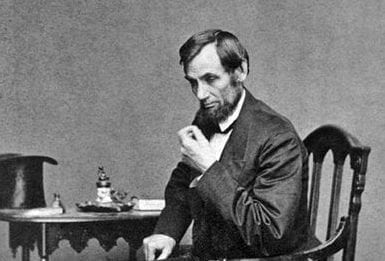

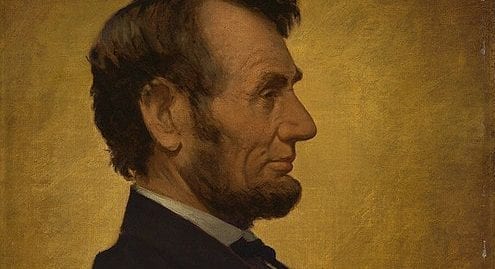

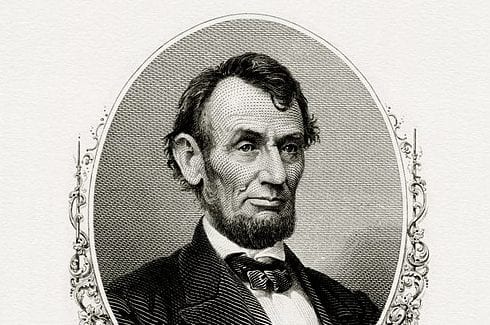

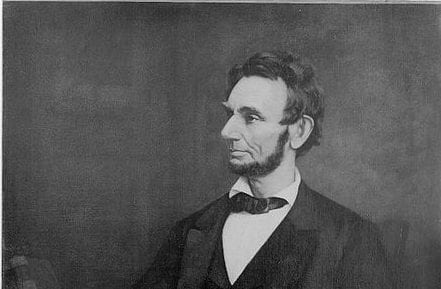

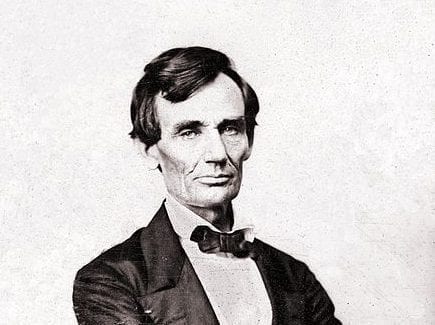

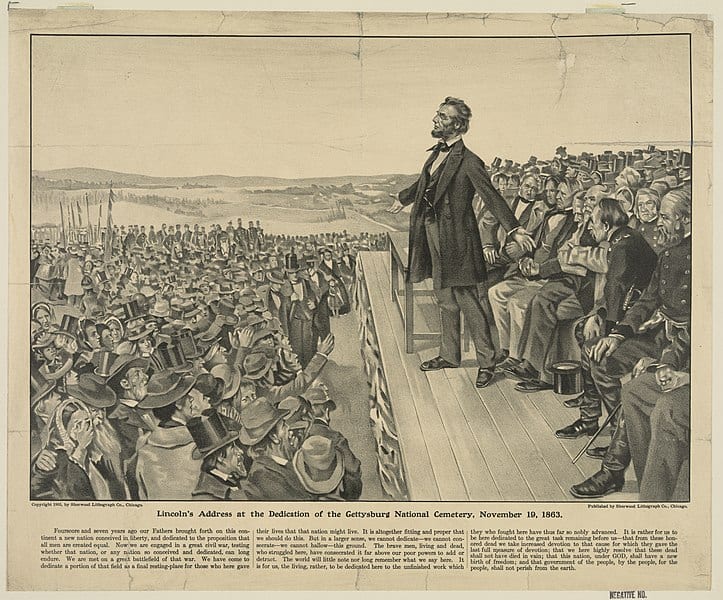

The case concerned a claim made by the family of William A. Lloyd, who allegedly was employed as a Union spy during the Civil War. Lloyd passed away after the war, and his estate, represented by Enoch Totten, sued the government for wages that had been promised to Lloyd by President Abraham Lincoln himself. The government had compensated Lloyd only for his expenses, not for the $200 a month that Lincoln had supposedly promised. Years later it was determined that the entire claim on behalf of the Lloyd family was fraudulent, but none of this was known at the time.

Justice Stephen Field delivered a short but decisive response to the Lloyd family’s request asking the Court to order the federal government to pay the back wages. Dismissing the authority of the courts to intervene in matters related to secret operations, Field argued that the control of such operations was entirely a matter for the executive branch, even in a case where an injustice may have occurred. The Court cited the importance of secrecy to protect the sources and methods used by the clandestine arms of the government, and endorsed the wide discretionary authority given to the president in this arena. These operations were, Justice Field wrote, “sometimes indispensable to the government.”

Thanks in part to rulings like Totten, which sanctioned these practices, covert operations in the service of American foreign policy became even more pronounced over the next one hundred years

92 U.S. 105, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/92/105.

MR. JUSTICE FIELD1 delivered the opinion of the Court.

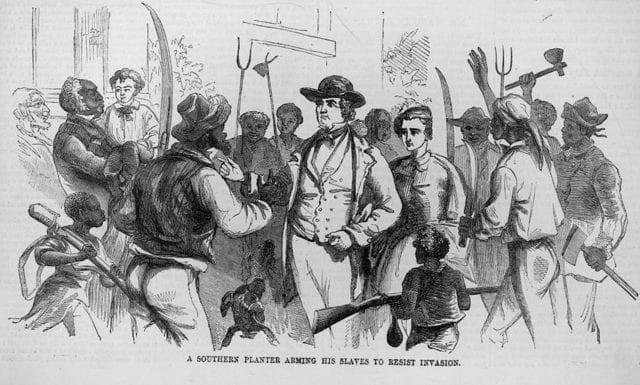

This case comes before us on appeal from the Court of Claims. The action was brought to recover compensation for services alleged to have been rendered by the claimant’s intestate,2 William A. Lloyd, under a contract with President Lincoln, made in July 1861, by which he was to proceed south and ascertain the number of troops stationed at different points in the insurrectionary states, procure plans of forts and fortifications, and gain such other information as might be beneficial to the government of the United States, and report the facts to the president; for which services he was to be paid $200 a month.

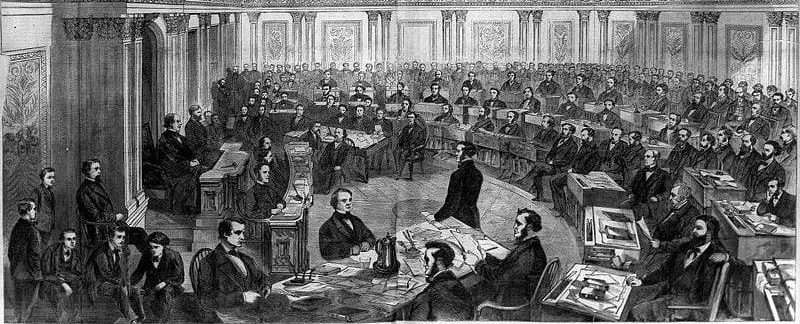

The Court of Claims3 finds that Lloyd proceeded under the contract within the rebel lines and remained there during the entire period of the war, collecting and from time to time transmitting information to the president, and that upon the close of the war he was only reimbursed his expenses. But the court, being equally divided in opinion as to the authority of the president to bind the United States by the contract in question, decided, for the purposes of an appeal, against the claim and dismissed the petition.

We have no difficulty at all to the authority of the president in the matter. He was undoubtedly authorized during the war, as commander-in-chief of the armies of the United States, to employ secret agents to enter the rebel lines and obtain information respecting the strength, resources, and movements of the enemy, and contracts to compensate such agents are so far binding upon the government as to render it lawful for the president to direct payment of the amount stipulated out of the contingent fund under his control. Our objection is not to the contract, but to the action upon it in the Court of Claims. The service stipulated by the contract was a secret service; the information sought was to be obtained clandestinely, and was to be communicated privately; the employment and the service were to be equally concealed. Both employer and agent must have understood that the lips of the other were to be forever sealed respecting the relation of either to the matter. This condition of the engagement was implied from the nature of the employment, and is implied in all secret employments of the government in time of war or upon matters affecting our foreign relations where a disclosure of the service might compromise or embarrass our government in its public duties or endanger the person or injure the character of the agent. If upon contracts of such a nature an action against the government could be maintained in the Court of Claims whenever an agent should deem himself entitled to greater or different compensation than that awarded to him, the whole service in any case, and the manner of its discharge, with the details of dealings with individuals and officers, might be exposed, to the serious detriment of the public. A secret service, with liability to publicity in this way, would be impossible, and, as such services are sometimes indispensable to the government, its agents in those services must look for their compensation to the contingent fund of the department employing them and to such allowance from it as those who dispense that fund may award. The secrecy which such contracts impose precludes any action for their enforcement. The publicity produced by an action would itself be a breach of a contract of that kind, and thus defeat a recovery.

It may be stated as a general principle that public policy forbids the maintenance of any suit in a court of justice the trial of which would inevitably lead to the disclosure of matters which the law itself regards as confidential and respecting which it will not allow the confidence to be violated. On this principle, suits cannot be maintained which would require a disclosure of the confidences of the confessional, or those between husband and wife, or of communications by a client to his counsel for professional advice, or of a patient to his physician for a similar purpose. Much greater reason exists for the application of the principle to cases of contract for secret services with the government, as the existence of a contract of that kind is itself a fact not to be disclosed.

Judgment affirmed.

- 1. Justice Stephen A. Field (1816–1899) was an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and former chief justice of the Supreme Court of California.

- 2. A person who dies without having made a will.

- 3. The Court of Claims, now the Court of Federal Claims, hears cases involving monetary claims against the federal government.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.