Introduction

Elizabeth Packard was married to a Presbyterian minister with whom she had six children. At some point in early 1860, Packard was invited by her Sunday school teacher to share her views on some elements of the denomination’s theology with which she disagreed. While her participation in the class seems to have been popular with the rest of the congregation, her divergence from the church’s official doctrines was not well-taken by the church officials. Under Illinois law at the time, it was possible for a husband to commit his wife to an institution for the mentally insane with nothing more than the opinion of a single medical professional as evidence.

Packard was held in the Jacksonville Insane Asylum for three years before she finally cajoled her way into a meeting with the asylum’s Board of Trustees and convinced them of her sanity. Packard then published an account of her institutionalization that was so compelling that the board ordered her husband to remove Packard from their institution. He did so, but then imprisoned her in their home while arranging for her permanent incarceration at an asylum out of state. Once again, Packard’s quick thinking proved her salvation: she was able to get word to a friend, who convinced a local judge to issue a writ of habeas corpus, forcing her husband to present himself with her in the court. There, the judge ordered Packard’s husband to “prove” her insanity during a jury trial, which he was unable to do.

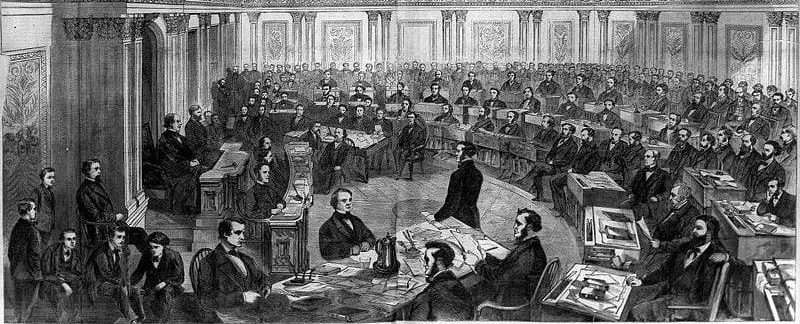

Following her harrowing experiences, Packard became an advocate for legal reforms that would make it impossible for married women to be institutionalized without a jury trial. In 1867, the Illinois legislature passed an “Act for the Protection of Personal Liberty,” which made institutionalization for insanity dependent upon the outcome of a jury trial and a judge’s order, and provided retroactively for the provision of such trials for all persons already institutionalized for insanity. We include a section from Packard’s address to the legislature in support of the bill, following an excerpt from her memoir.

Source: Elizabeth Packard, Marital Power Exemplified in Mrs. Packard’s Trial . . . (Chicago: Clarke & Co., 1870), available at https://archive.org/details/maritalpowerexem00pack/page/n5/mode/2up.

. . . It was in a Bible-class in Manteno, Kankakee County, Illinois, that I defended some religious opinions which conflicted with the Creed of the Presbyterian Church in that place, which brought upon me the charge of insanity. It was at the invitation of Deacon Dole, the teacher of that Bible-class, that I consented to become his pupil, and it was at his special request that I brought forward my views to the consideration of the class. The class numbered six when I entered it, and forty-six when I left it. I was about four months a member of it; I had not the least suspicion of danger or harm arising in any way, either to myself or others, from thus complying with his wishes, and thus uttering some of my honestly cherished opinions. I regarded the principle of religious tolerance as the vital principle on which our government was based, and I in my ignorance supposed this right was protected to all American citizens, even to the wives of clergymen. But, alas! my own sad experience has taught me the danger of believing a lie on so vital a question. The result was, I was legally kidnapped and imprisoned three years simply for uttering these opinions under these circumstances.

I was kidnapped in the following manner. Early on the morning of the 18th of June, 1860, as I arose from my bed, preparing to take my morning bath, I saw my husband approaching my door with our two physicians, both members of his church and of our Bible-class, and a stranger gentleman, Sheriff Burgess. Fearing exposure, I hastily locked my door and proceeded with the greatest dispatch to dress myself. But before I had hardly commenced, my husband forced an entrance into my room through the window with an axe! And I, for shelter and protection against an exposure in a state of almost entire nudity, sprang into bed, just in time to receive my unexpected guests. The trio approached my bed, and each doctor felt my pulse, and without asking a single question both pronounced me insane. So it seems that in the estimation of these two M.D.s, Dr. Merrick and Dr. Newkirk, insanity is indicated by the action of the pulse instead of the mind! . . . This was the only medical examination I had. This was the only trial of any kind that I was allowed to have to prove the charge of insanity brought against me by my husband. I had no chance of self-defense whatever.

My husband then informed me that the “forms of law” were all complied with, and he therefore requested me to dress myself for a ride to Jacksonville, to enter the Insane Asylum as an inmate. I objected, and protested against being imprisoned without any trial. But to no purpose. My husband insisted upon it that I had no protection in the law but himself, and that he was doing by me just as the laws of the state allowed him to do. I could not then credit this statement, but now know it to be too sadly true; for the statute of Illinois expressly states that a man may put his wife into an insane asylum without evidence of insanity.[1] . . .

I told my husband I should not go voluntarily into the asylum, and leave my six children and my precious babe of eighteen months, without some kind of trial. . . . I was soon in the hands of the sheriff, who forced me from my home by ordering two men to carry me to the wagon which took me to the depot. Esquire Labrie, our nearest neighbor, who witnessed this scene, said he was willing to testify before any court under oath that “Mrs. Packard was literally kidnapped.” I was carried to the cars from the depot in the arms of two strong men, whom my husband appointed for this purpose, amid the silent and almost speechless gaze of a large crowd of citizens who had collected for the purpose of rescuing me from the hands of my persecutors. But they were prevented from executing their purpose by the lie Deacon Dole was requested by my husband to tell the excited crowd, viz: that “The Sheriff has legal papers to defend this proceeding,” and they well knew that for them to resist the sheriff, the laws would expose themselves to imprisonment. . . .

When once in the asylum I was beyond the reach of all human aid, except what could come through my husband, since the law allows no one to take them out, except the one who put them in, or by his consent; and my husband determined never to take me out, until I recanted my new opinions, claiming that I was incurably insane so long as I could not return to my old standpoint of religious belief. Of course, I could not believe at my option, but only as light and evidence was presented to my own mind, and I was too conscientious to act the hypocrite, by professing to believe what I could not believe. I was therefore pronounced “hopelessly insane.”. . .

In this defenseless, deplorable condition I lay closely imprisoned three years. . . . At the expiration of three years, my oldest son, Theophilus, became of age, when he immediately availed himself of his manhood, by a legal compromise with his father and the Trustees, wherein he volunteered to hold himself wholly responsible for my support for life, if his father would only consent to take me out of my prison. This proposition was accepted by Mr. Packard, with this proviso: that if ever I returned to my own home and children he should put me in again for life. The Trustees had previously notified Mr. Packard that I must be removed, as they should keep me no longer. Had not this been the case, my son’s proposition would doubtless have been rejected by him.

The reasons why the Trustees took this position was, because they became satisfied that I was not a fit subject for that institution, in the following manner: On one of their official visits to the institution, I coaxed Dr. McFarland, superintendent of the asylum, to let me go before them and ”fire a few guns at Calvinism,”[2] as I expressed myself, that they might know and judge for themselves whether I deserved a life-long imprisonment for indulging such opinions. Dr. McFarland replied to my request, that the Trustees were Calvinists, and the chairman a member of the Presbyterian Synod of the United States.[3]

“Never mind,” said I, “I don’t care if they are, I am not afraid to defend my opinions even before the Synod itself. I don’t want to be locked up here all my lifetime without doing something. But if they are Calvinists,” I added,” you may be sure they will call me insane, and then you will have them to back you up in your opinion and position respecting me.”

This argument secured his consent to let me go before them. He also let me have two sheets of paper to write my opinions upon. With my document prepared, or “gun loaded,” as I called it, and examined by the Doctor to see that all was right, that is, that it contained no exposures of himself, I entered the Trustees’ room. . . . After being politely and formally introduced to the Trustees, individually, I was seated by the chairman, to receive his permission to speak, in the following words: “Mrs. Packard, we have heard Mr. Packard’s statement, and the Doctor said you would like to speak for yourself. We will allow you ten minutes for that purpose.”

I then . . . commenced reading my document in a quiet, calm, clear, tone of voice. It commenced with these words: “Gentlemen, I am accused of teaching my children doctrines ruinous in their tendency, and such as alienate them from their father. I reply, that my teachings and practice both, are ruinous to Satan’s cause, and do alienate my children from Satanic influences. I teach Christianity, my husband teaches Calvinism. They are antagonistic systems and uphold antagonistic authorities. Christianity upholds God’s authority; Calvinism the devil’s authority,” etc., etc.

Thus I went on, most dauntlessly and fearlessly contrasting the two systems, as I viewed them, until my entire document was read, without being interrupted, although my time had more than expired. Confident I had secured their interest as well as attention, I ventured to ask if I might be allowed to read another document I held in my hand, which the Doctor had not seen. The request was voted upon and met not only with an unanimous response in the affirmative, but several cried out: “Let her go on! Let us hear the whole!” This document bore heavily upon Mr. Packard and the Doctor both. Still I was tolerated. The room was so still I could have heard a clock tick. When I had finished, instead of then dismissing me, they commenced questioning me, and I only rejoiced to answer their questions, being careful however not to let slip any chance I found to expose the darkest parts of this foul conspiracy, wherein Mr. Packard and their Superintendent were the chief actors. Packard and McFarland both sat silent and speechless, while I fearlessly exposed their wicked plot against my personal liberty and my rights. They did not deny or contradict one statement I made, although so very hard upon them both.

Thus nearly one hour was passed. . . .These intelligent men at once endorsed my statement, and became my friends. They offered me my liberty at once, and said that anything I wanted they stood ready to do for me. Mr. Brown, the Chairman, said he saw it was of no use for me to go to my husband; but said they would send me to my children if I wished to go, or to my father in Massachusetts, or they would board me up[4] in Jacksonville. I thanked them for their kind and generous offers. “But,” said I, “it is of no use for me to accept of any one of them, for I am still Mr. Packard’s wife, and there is no law in America to protect a wife from her husband. I am not safe from him outside these walls, on this continent, unless I flee to Canada.”. . .

These manly gentlemen apprehended my sad condition and expressed their real sympathy for me, but did not know what to advise me to do. Therefore, they left it to me and the Doctor to do as we might think best. I suggested to the Doctor that I write a book, and in this manner lay my case before the People—the government of the United States and ask for the protection of the laws. . . . This occupied me nine months, which completed my three years of prison life.

The Trustees now ordered Mr. Packard to take me away, as no one else could legally remove me. I protested against being put into his hands without some protection . . . but . . . as I entered the asylum against my will, and in spite of my protest, so I was put out of it into the absolute power of my persecutor again, against my will, and in spite of my protest to the contrary. . . .

I returned to my husband and little ones, only to be again treated as a lunatic. He cut me off from communication with this community, and my other friends, by intercepting my mail; made me a close prisoner in my own house; refused me interviews with friends who called to see me, so that he might meet with no interference in carrying out the plan he had devised to get me incarcerated again for life. . . .

. . . I determined upon the following expedient as my last and only resort, as a self-defensive act.

There was a stranger man who passed my window daily to get water from our pump. One day as he passed I beckoned to him to take a note which I had pushed down through where the windows come together (my windows were firmly nailed down and screwed together, so that I could not open them) directed to Mrs. A. C. Haslett, the most efficient friend I knew of in Manteno, wherein I informed her of my imminent danger, and begged of her if it was possible in any way to rescue me to do so, forthwith. . . . Mrs. Haslett sympathized with me; . . . therefore she sought council of Judge Starr of Kankakee City, to know if any law could reach my case so as to give me the justice of a trial of any kind, before another incarceration. The Judge told her that if I was a prisoner in my own house, and any were willing to take oath upon it, a writ of habeas corpus might reach my case and thus secure me a trial. Witnesses were easily found who could take oath to this fact, as many had called at our house to see that my windows were screwed together on the outside, and our front outside door firmly fastened on the outside, and our back outside door most vigilantly guarded by day and locked by night.

In a few days this writ was accordingly executed by the sheriff of the county, and just two days before Mr. Packard was intending to start with me for Massachusetts to imprison me for life in Northampton Lunatic Asylum he was required by this writ to bring me before the court and give his reasons to the court why he kept his wife a prisoner. The reason he gave for so doing was that I was insane. The Judge replied, “Prove it!” The Judge then empanelled a jury of twelve men, and the following trial ensued as the result. This trial continued five days. Thus my being made a prisoner at my own home was the only hinge on which my personal liberty for life hung, independent of mob law, as there is no law in the state that will allow a married woman the right of a trial against the charge of insanity brought against her by her husband; and God only knows how many innocent wives and mothers my case represents, who have thus lost their liberty for life by this arbitrary power, unchecked as it is by no law on the statute book of Illinois.

Mrs. Packard’s Address to the Illinois Legislature (1867)

. . . Gentlemen, we married women need emancipation; and will you not be the pioneer state in our Union, in woman’s emancipation? and thus use my martyrdom for the identity of a married woman, to herald this most glorious of all reforms—married woman’s legal emancipation, from that of a slave in law, to that of a partner and companion of her husband, in law, as she now is in society?

And, lest there be a misunderstanding on this subject, permit me here to explain what kind of slavery I refer to. This slavish position which the principles of common law assigns the married woman, is a relic of barbarism, which the progress of civilization will, doubtless, ere long, annihilate. In the dark ages, married woman was a slave to her husband, both socially and legally, but, as civilization has progressed, she has outgrown her social position—that of a slave—and is now regarded in society as the companion and partner of her husband. But the law has not progressed with civilization, so that married woman is still a slave, legally, while she is his companion, socially.

Man, we know, is woman’s natural protector, and, in most instances, is all the protection a married woman needs. Still, as the laws are made for the exceptional cases, where man is not a law unto himself, what can be the harm in emancipating woman from this slavish position, so that she can receive governmental protection of her right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” as well as the marital protection? So, in case where the marital fails, she can have legal protection, while married as well as when single. Then when your darling daughter is called to exchange the paternal protection for the marital, she will not be obliged to alienate her right to governmental protection by this exchange of her natural protectors, but she, the tenderest and the best, can then claim of her government, while a married woman, the same protection of her rights as a woman, which your sons now claim as men.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.