No related resources

Introduction

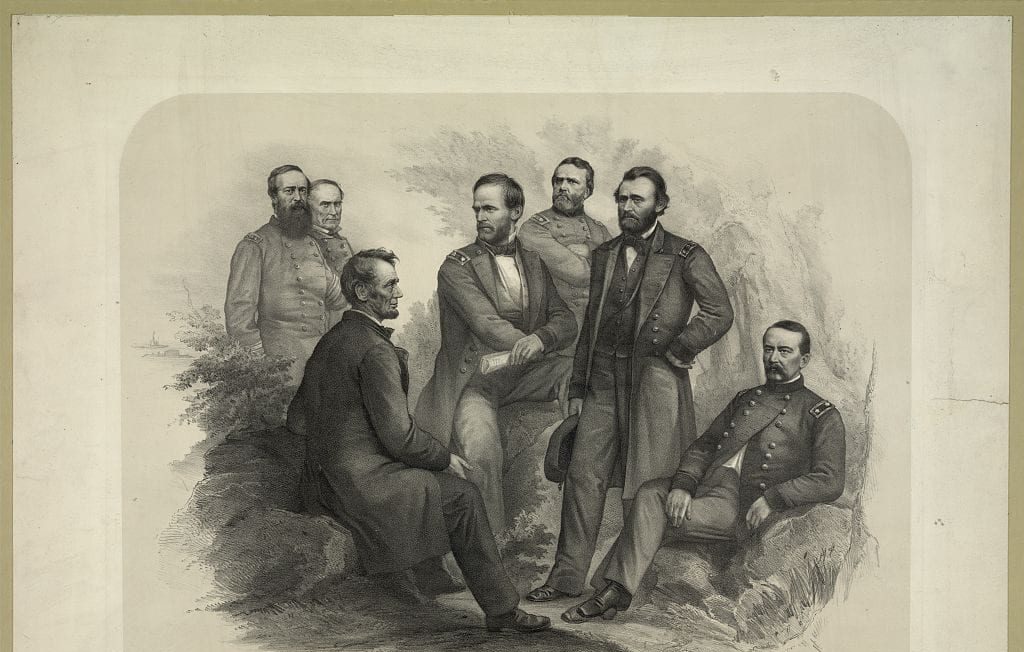

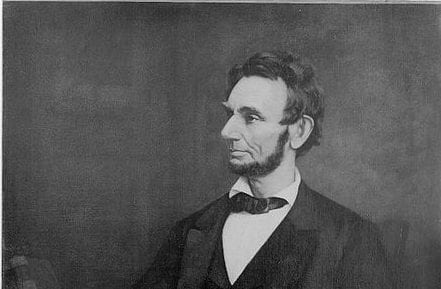

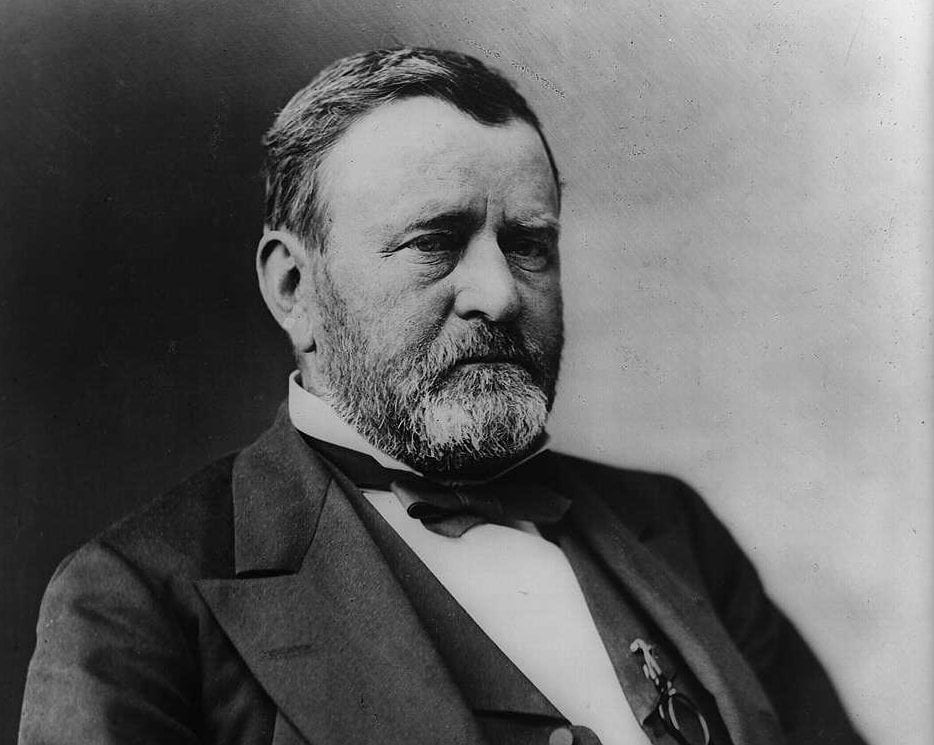

Since the 1840s the United States had flirted with the idea of developing a relationship with the strategically located nation of Santo Domingo (today known as the Dominican Republic) hoping to acquire a usable naval base for its growing fleet. Under President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of State William Seward (1801–1872) attempted to negotiate a treaty permitting the United States to use a portion of the island for such a base. That effort failed. When Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) was elected president in 1868, however, another attempt was made to gain access to the island, preferably by acquiring it outright. Grant selected Orville Babcock (1835–1884), one of his personal secretaries and a former Civil War staff officer, to travel to Santo Domingo in 1869. Babcock was verbally instructed by the president to go beyond his written State Department instructions and, as Grant later recalled, “ascertain so far as he could the wishes of the Dominican people and government with respect to annexation.”

Babcock found the Dominican government open to negotiating for annexation. After a series of secret meetings, the two nations agreed to proceed with annexation. President Grant was delighted with the news, observing that the island was strategically vital, “the gate to the Caribbean . . . in case of a maritime war it would give us a foothold in the West Indies of inestimable value.” Grant also raised an argument that would be used by many proponents of American expansion: if the United States did not control the island, European powers surely would. Santo Domingo was “weak and must go somewhere for protection.” Was “the United States willing that she should seek protection from a foreign power? Such a confession would be to abandon the Monroe Doctrine.”

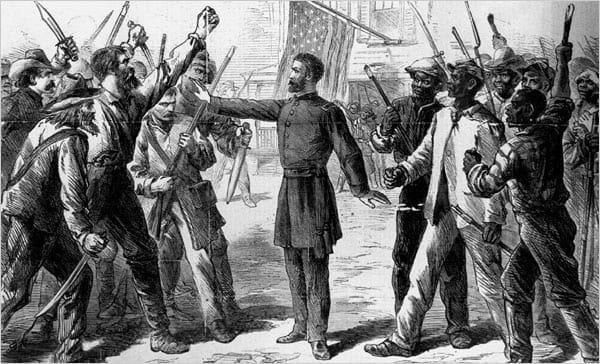

In an interesting twist to the conventional case for expansion, Grant added that by acquiring Santo Domingo the United States would advance the cause of abolishing slavery in the Western Hemisphere. The United States imported tobacco, chocolate, and fruit from Cuba and Brazil, both slave nations, and by acquiring Santo Domingo would undermine those slave-based regimes by using the island as an alternative source for these commodities. Grant noted, “Santo Domingo in the hands of the United States would make slave labor unprofitable and would soon extinguish that hated system of enforced labor.”

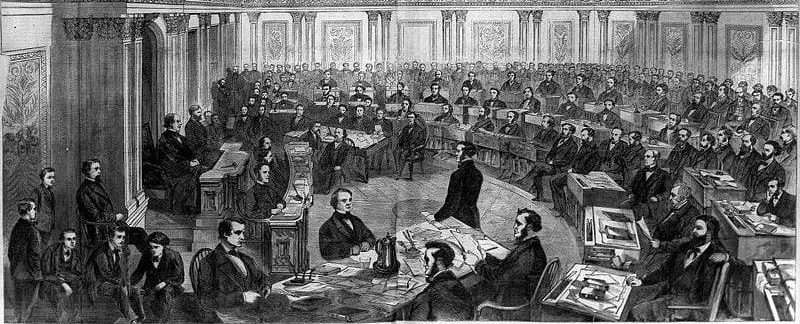

Grant’s vision did not come to pass. A month after receiving Grant’s message, the U.S. Senate split twenty-eight to twenty-eight on the treaty, well short of the necessary two-thirds vote needed to ratify. Opponents offered an array of arguments against annexation: some objected on the grounds of race, others over annexing a predominantly Catholic nation; others were concerned about empire building and enriching American capitalists who would exploit the island. The contentious debate over the annexation of Santo Domingo presaged the battles that would occur into the early twentieth century about the costs, literally and figuratively, of American imperialism.

Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate, vol. 19, 41st Congress, 2nd session, Library of Congress, 460–62, http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/ampagecollId=llej&fileName=019/llej019.db&recNum=459&itemLink=D?hlaw:9:./temp/~ammem_rkzb::%230190461&linkText=1.

I transmit to the Senate, for consideration with a view to its ratification, an additional article to the treaty of the 29th of November last,1 for the annexation of the Dominican Republic to the United States, stipulating for an extension of the time for exchanging the ratifications thereof, signed in this city on the 14th instant,2 by the plenipotentiaries of the parties.

It was my intention to have also negotiated with the plenipotentiary of San Domingo amendments to the treaty of annexation to obviate objections which may be urged against the treaty as it is now worded; but on reflection I deem it better to submit to the Senate the propriety of their amending the treaty as follows: First, to specify that the obligations of this government shall not exceed the $1,500,000 stipulated in the treaty; secondly, to determine the manner of appointing the agents to receive and disburse the same; thirdly, to determine the class of creditors who shall take precedence in the settlement of their claims; and, finally, to insert such amendments as may suggest themselves to the minds of senators to carry out in good faith the conditions of the treaty submitted to the Senate of the United States in January last, according to the spirit and intent of that treaty. From the most reliable information I can obtain, the sum specified in the treaty will pay every just claim against the Republic of San Domingo and leave a balance sufficient to carry on a territorial government until such time as new laws for providing a territorial revenue can be enacted and put in force.

I feel an unusual anxiety for the ratification of this treaty, because I believe it will redound greatly to the glory of the two countries interested, to civilization, and to the extirpation of the institution of slavery.

The doctrine promulgated by President Monroe3 has been adhered to by all political parties, and I now deem it proper to assert the equally important principle that hereafter no territory on this continent shall be regarded as subject of transfer to a European power. The government of San Domingo has voluntarily sought this annexation. It is a weak power, numbering probably less than 120,000 souls, and yet possessing one of the richest territories under the sun, capable of supporting a population of 10,000,000 people in luxury. The people of San Domingo are not capable of maintaining themselves in their present condition, and must look for outside support. They yearn for the protection of our free institutions and laws, our progress and civilization. Shall we refuse them?

I have information which I believe reliable that a European power stands ready now to offer $2,000,000 for the possession of Samana Bay4 alone. If refused by us, with what grace can we prevent a foreign power from attempting to secure the prize?

The acquisition of San Domingo is desirable because of its geographical position. It commands the entrance to the Caribbean Sea and the Isthmus transit of commerce. It possesses the richest soil, best and most capacious harbors, most salubrious climate, and the most valuable products of the forests, mine, and soil of any of the West India Islands. Its possession by us will in a few years build up a coastwise commerce of immense magnitude, which will go far toward restoring to us our lost merchant marine. It will give to us those articles which we consume so largely and do not produce, thus equalizing our exports and imports. In case of foreign war it will give us command of all the islands referred to, and thus prevent an enemy from ever again possessing himself of rendezvous upon our very coast.

At present our coast trade between the states bordering on the Atlantic and those bordering on the Gulf of Mexico is cut into by the Bahamas and the Antilles. Twice we must, as it were, pass through foreign countries to get by sea from Georgia to the west coast of Florida.

San Domingo, with a stable government, under which her immense resources can be developed, will give remunerative wages to tens of thousands of laborers not now on the island.

This labor will take advantage of every available means of transportation to abandon the adjacent islands and seek the blessings of freedom and its sequence—each inhabitant receiving the reward of his own labor. Puerto Rico and Cuba will have to abolish slavery, as a measure of self-preservation to retain their laborers.

San Domingo will become a large consumer of the products of northern farms and manufactories. The cheap rate at which her citizens can be furnished with food, tools, and machinery will make it necessary that the contiguous islands should have the same advantages in order to compete in the production of sugar, coffee, tobacco, tropical fruits, etc. This will open to us a still wider market for our products.

The production of our own supply of these articles will cut off more than one hundred millions of our annual imports, besides largely increasing our exports. With such a picture it is easy to see how our large debt abroad is ultimately to be extinguished. With a balance of trade against us (including interest on bonds held by foreigners and money spent by our citizens traveling in foreign lands) equal to the entire yield of the precious metals in this country, it is not so easy to see how this result is to be otherwise accomplished.

The acquisition of San Domingo is an adherence to the “Monroe doctrine”; it is a measure of national protection; it is asserting our just claim to a controlling influence over the great commercial traffic soon to flow from east to west by the way of the Isthmus of Darien;5 it is to build up our merchant marine; it is to furnish new markets for the products of our farms, shops, and manufactories; it is to make slavery insupportable in Cuba and Porto Rico at once and ultimately so in Brazil; it is to settle the unhappy condition of Cuba, and end an exterminating conflict;6 it is to provide honest means of paying our honest debts without overtaxing the people; it is to furnish our citizens with the necessaries of everyday life at cheaper rates than ever before; and it is, in fine, a rapid stride toward that greatness which the intelligence, industry, and enterprise of the citizens of the United States entitle this country to assume among nations.

- 1. Orville Babcock signed the treaty for the annexation of Santo Domingo on November 29, 1869.

- 2. Of this month.

- 3. he Monroe Doctrine.

- 4. Samana Bay is in the eastern portion of the Dominican Republic. From Franklin Pierce’s presidency through that of Ulysses S. Grant, the government expressed an interest in acquiring this bay to serve as a base for the U.S. Navy.

- 5. Also known as the Isthmus of Panama; presently the nation of Panama.

- 6. A rebellion against Spanish rule had begun on Cuba in 1868.

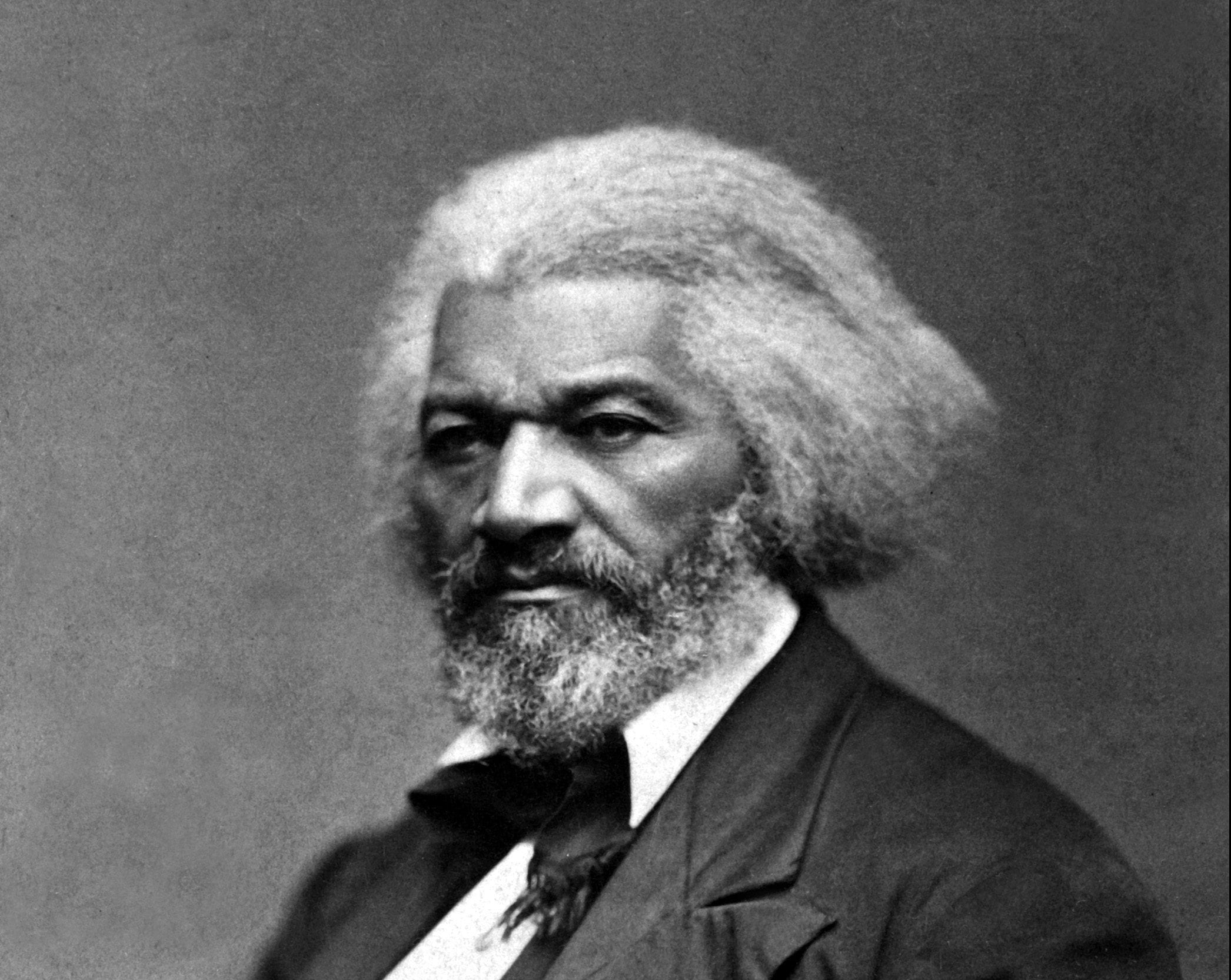

Address at Cooper Union

June 16, 1870

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.