No related resources

Introduction

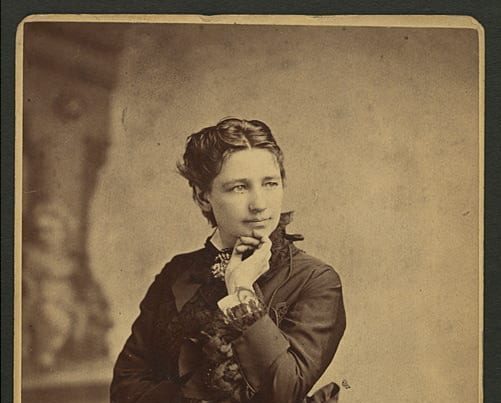

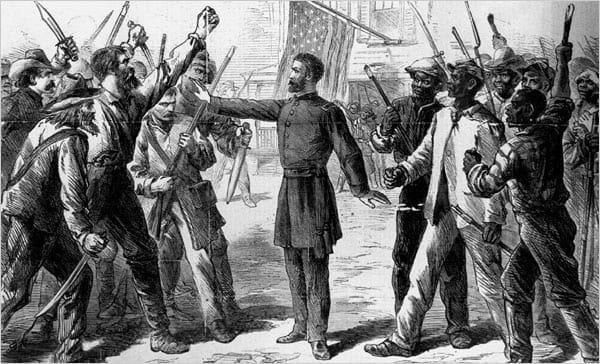

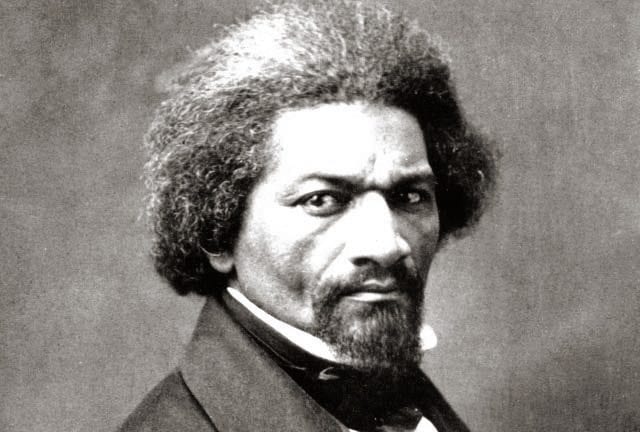

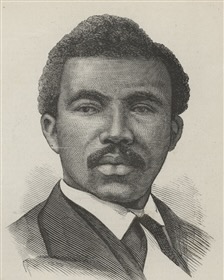

Robert Brown Elliott (1842–1884) was born in Liverpool, England, and educated at Eton College, a prestigious boarding school, graduating in 1859. He studied law, served in the British Royal Navy, and then immigrated to America, settling in South Carolina in 1867. He resumed his law studies and began to practice law in Columbia in 1868. That same year he served as delegate to the state constitutional convention and thus commenced a short but distinguished career in public office. A determined adversary of the Ku Klux Klan, he was elected to the state legislature and later appointed commanding general of the South Carolina National Guard, the first African American to serve in that position. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1870 and remained there until 1874, when he resigned to seek office again at the state level. In 1875 he was elected Speaker of the South Carolina General Assembly, and the following year was elected state attorney general. In 1879 he accepted appointment as a customs inspector for the U.S. Treasury Department, which relocated him to New Orleans. He died there of malaria in 1884.

In the decade following the end of the Civil War, commonly known as the Reconstruction era, Congress and the states enacted the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, and Congress enacted a series of statutory laws designed to abolish slavery and to secure the civil and political rights of the country’s newly emancipated citizens. In this selection and the two that follow it, Representative Elliott and then the U.S. Supreme Court present early interpretations of the Fourteenth Amendment, the central and most complex of the three Reconstruction amendments. Of primary importance is section 1 of that amendment, which provides: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” (see appendix B).

Controversies immediately arose over how to interpret this language. Here is the fundamental question: Is the Fourteenth Amendment a mandate to secure specific sets of rights to all citizens or persons, or is it only an equal rights/nondiscrimination mandate? In other words, does this amendment, by its “privileges or immunities” and “due process” clauses, impose on the states duties to secure to all citizens or persons within their jurisdictions newly expanded, federally defined sets of rights? Or does it leave intact states’ traditional authority to define civil rights as they see fit, requiring only that, however they define them, states secure those rights equally to all citizens or persons irrespective of race or color?

In 1873, ruling on a combined set of cases known as the Slaughterhouse Cases (83 U.S. 36), the U.S. Supreme Court provided its early answer to this question. The Court upheld Louisiana’s grant of monopoly privileges to a New Orleans slaughterhouse, thus rejecting a claim by a group of butchers that the Fourteenth Amendment created a federally mandated right to pursue a lawful occupation. According to the Court majority, under the Fourteenth Amendment the states retain their traditional authority to define the civil rights of persons and citizens within their jurisdictions. Explaining its ruling, the Court added that the amendment is properly understood as an equal rights or antidiscrimination law—in particular, as a protection, for those lately emancipated, against antiblack discrimination. This meant that the justices regarded the equal protection clause, rather than the privileges or immunities clause or the due process clause, as the Fourteenth Amendment’s primary provision for achieving its overall objective. Writing for the Court, Justice Samuel Miller (1816–1890) opined that “the one pervading purpose” of the Reconstruction-era amendments is “the freedom of the slave race, the security and firm establishment of that freedom, and the protection of the newly made freeman and citizen from the oppressions of those who had formerly exercised unlimited dominion over him.”

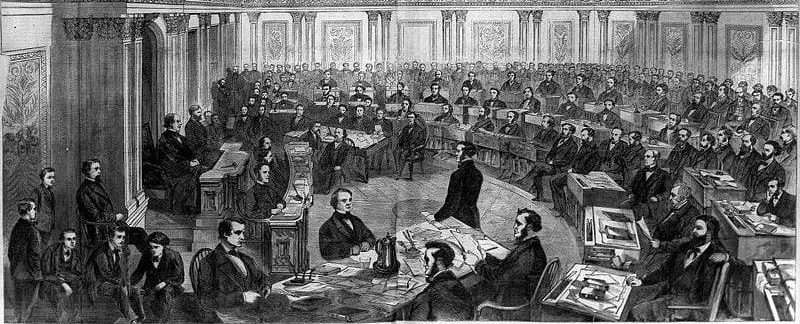

In the speech excerpted here, Representative Elliott urges the adoption, against southern legislators’ objections, of what would prove to be the final civil rights measure enacted by the U.S. government in the Reconstruction era. The bill became the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Arguing for the bill’s passage, Elliott engages the pertinent constitutional issues, maintaining that the proposed law is authorized by the Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted in the Slaughterhouse Cases. Less than a decade later, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the law unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases.

Source: Congressional Record, House of Representatives, 43rd Congress, 1st session, vol. 2, 407–11; available at A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875, http://www.memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage. The annotations of applause in brackets are in the original document.

While I am sincerely grateful for this high mark of courtesy that has been accorded to me by this House, it is a matter of regret to me that it is necessary at this day that I should rise in the presence of an American Congress to advocate a bill which simply asserts equal rights and equal public privileges for all classes of American citizens. I regret, sir, that the dark hue of my skin may lend a color to the imputation that I am controlled by motives personal to myself in my advocacy of this great measure of national justice. Sir, the motive that impels me is restricted by no such narrow boundary but is as broad as your Constitution. I advocate it, sir, because it is right. . . .

But, sir, we are told by the distinguished gentleman from Georgia1 that Congress has no power under the Constitution to pass such a law, and that the passage of such an act is in direct contravention of the rights of the states. I cannot assent to any such proposition. The constitution of a free government ought always to be construed in favor of human rights. Indeed, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, in positive words, invest Congress with the power to protect the citizen in his civil and political rights. Now, sir, what are civil rights: rights natural, modified by civil society. . . .

Alexander Hamilton, the right-hand man of Washington in the perilous days of the then infant republic, the great interpreter and expounder of the Constitution, says:

Natural liberty is a gift of the beneficent Creator to the whole human race: civil liberty is founded on it: civil liberty is only natural liberty modified and secured by civil society.2

….These amendments,3 one and all, are thus declared4 to have as their all-pervading design and end the security to the recently enslaved race, not only their nominal freedom, but their complete protection from those who had formerly exercised unlimited dominion over them. It is in this broad light that all these amendments must be read, the purpose to secure the perfect equality before the law of all citizens of the United States. What you give to one class you must give to all; what you deny to one class you shall deny to all, unless in the exercise of the common and universal police power5 of the state you find it needful to confer exclusive privileges on certain citizens, to be held and exercised still for the common good of all. . . .

But each of these gentlemen quote at some length from the decision of the court to show that the court recognizes a difference between citizenship of the United States and citizenship of the states. That is true, and no man here who supports this bill questions or overlooks the difference. There are privileges and immunities which belong to me as a citizen of the United States, and there are privileges and immunities which belong to me as a citizen of my state. The former are under the protection of the Constitution and laws of the United States, and the latter are under the protection of the constitution and laws of my state. But what of that? Are the rights which I now claim—the right to enjoy the common public conveniences of travel on public highways, of rest and refreshment at public inns, of education in public schools, of burial in public cemeteries—rights which I hold as a citizen of the United States or of my state? Or, to state the question more exactly, is not the denial of such privileges to me a denial to me of the equal protection of the laws? For it is under this clause of the Fourteenth Amendment that we place the present bill, no state shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” No matter, therefore, whether his rights are held under the United States or under his particular state, he is equally protected by this amendment. He is always and everywhere entitled to the equal protection of the laws. All discrimination is forbidden; and while the rights of citizens of a state as such are not defined or conferred by the Constitution of the United States, yet all discrimination, all denial of equality before the law, all denial of the equal protection of the laws, whether state or national laws, is forbidden. . . .

. . .The Fourteenth Amendment does not forbid a state to deny to all its citizens any of those rights which the state itself has conferred, with certain exceptions, which are pointed out in the decision which we are examining. What it does forbid is inequality, is discrimination, or, to use the words of the amendment itself, is the denial “to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” If a state denies to me rights which are common to all her other citizens, she violates this amendment, unless she can show, as was shown in the Slaughter-House Cases, that she does it in the legitimate exercise of her police power. If she abridges the rights of all her citizens equally, unless those rights are specially guarded by the Constitution of the United States, she does not violate this amendment. This is not to put the rights which I hold by virtue of my citizenship of South Carolina under the protection of the national government; it is not to blot out or overlook in the slightest particular the distinction between rights held under the United States and rights held under the states; but it seeks to secure equality; to prevent discrimination, to confer as complete and ample protection on the humblest as on the highest. . . .

Now, sir, recurring to the venerable and distinguished gentleman from Georgia, who has added his remonstrance against the passage of this bill, permit me to say that I share in the feeling of high personal regard for that entleman which pervades this House. His years, his ability, and his long experience in public affairs entitle him to the measure of consideration which has been accorded to him on this floor. But in this discussion I cannot and I will not forget that the welfare and rights of my whole race in this country are involved. When, therefore, the honorable gentleman from Georgia lends his voice and influence to defeat this measure, I do not shrink from saying that it is not from him that the American House of Representatives should take lessons in matters touching human rights or the joint relations of the state and national governments. . . .[W]hen he comes again upon this national arena, and throws himself with all his power and influence across the path which leads to the full enfranchisement of my race, I meet him only as an adversary; nor shall age or any other consideration restrain me from saying that he now offers this government, which he has done his utmost to destroy, a very poor return for its magnanimous treatment, to come here and seek to continue, by the assertion of doctrines obnoxious to the true principles of our government, the burdens and oppressions which rest upon five millions of his countrymen who never failed to lift their earnest prayers for the success of this government when the gentleman was seeking to break up the union of these states and to blot the American republic from the galaxy of nations. [Loud applause.]

Sir, it is scarcely twelve years since that gentleman shocked the civilized world by announcing the birth of a government which rested on human slavery as its cornerstone.6 The progress of events has swept away that pseudo-government which rested on greed, pride, and tyranny; and the race whom he then ruthlessly spurned and trampled on are here to meet him in debate, and to demand that the rights which are enjoyed by their former oppressors—who vainly sought to overthrow a government which they could not prostitute to the base uses of slavery—shall be accorded to those who even in the darkness of slavery kept their allegiance true to freedom and the Union. Sir, the gentleman from Georgia has learned much since 1861; but he is still a laggard. Let him put away entirely the false and fatal theories which have so greatly marred an otherwise enviable record. Let him accept, in its fullness and beneficence, the great doctrine that American citizenship carries with it every civil and political right which manhood can confer. Let him lend his influence, with all his masterly ability, to complete the proud structure of legislation which makes his nation worthy of the great declaration which heralded its birth, and he will have done that which will most nearly redeem his reputation in the eyes of the world, and best vindicate the wisdom of that policy which has permitted him to regain his seat upon this floor. . . .

No language could convey a more complete assertion of the power of Congress over the subject embraced in the present bill than is here expressed. If the states do not conform to the requirements of this clause, if they continue to deny to any person within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, or as the Supreme Court had said, “deny equal justice in its courts,” then Congress is here said to have power to enforce the constitutional guarantee by appropriate legislation. That is the power which this bill now seeks to put in exercise. It proposes to enforce the constitutional guarantee against inequality and discrimination by appropriate legislation. It does not seek to confer new rights, nor to place rights conferred by state citizenship under the protection of the United States, but simply to prevent and forbid inequality and discrimination on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Never was there a bill more completely within the constitutional power of Congress. Never was there a bill which appealed for support more strongly to that sense of justice and fair play which has been said, and in the main with justice, to be a characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race. The Constitution warrants it; the Supreme Court sanctions it; justice demands it. . . .

The results of the war, as seen in Reconstruction, have settled forever the political status of my race. The passage of this bill will determine the civil status, not only of the Negro, but of any other class of citizens who may feel themselves discriminated against. It will form the capstone of that temple of liberty, begun on this continent under discouraging circumstances, carried on in spite of the sneers of monarchists and the cavils of pretended friends of freedom, until at last it stands in all its beautiful symmetry and proportions, a building the grandest which the world has ever seen, realizing the most sanguine expectations and the highest hopes of those who, in the name of equal, impartial, and universal liberty, laid the foundation stones.

The Holy Scriptures tell us of a humble handmaiden who long, faithfully, and patiently gleaned in the rich fields of her wealthy kinsman; and we are told further that at last, in spite of her humble antecedents, she found complete favor in his sight. For over two centuries our race had “reaped down your fields.” The cries and woes which we have uttered have “entered into the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth,”7 and we are at last politically free. The last vestiture only is needed—civil rights. Having gained this, we may, with hearts overflowing with gratitude, and thankful that our prayer has been granted, repeat the prayer of Ruth: “Entreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee; for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy god my God; where thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried; the Lord do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part thee and me.”8 [Great applause.]

- 1. Alexander Stephens (1812–1883) was the former vice president of the Confederate States of America and in 1874 was a U.S. representative from Georgia.

- 2. Alexander Hamilton, The Farmer Refuted, February 23, 1775. Elliott’s quotation is imprecise.

- 3. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

- 4. Elliott refers to the US Supreme Court’s ruling in the Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873).

- 5. “Police power” is a legal term referring to government’s power to make regulations to promote the public’s health, safety, welfare, or morals.

- 6. Elliott refers to Stephens’ “Cornerstone Speech” of March 21, 1861; available at https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/cornerstone-speech/.

- 7. James 5:4.

- 8. Ruth 1:16.

Annual Message to Congress (1874)

December 07, 1874

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.