Introduction

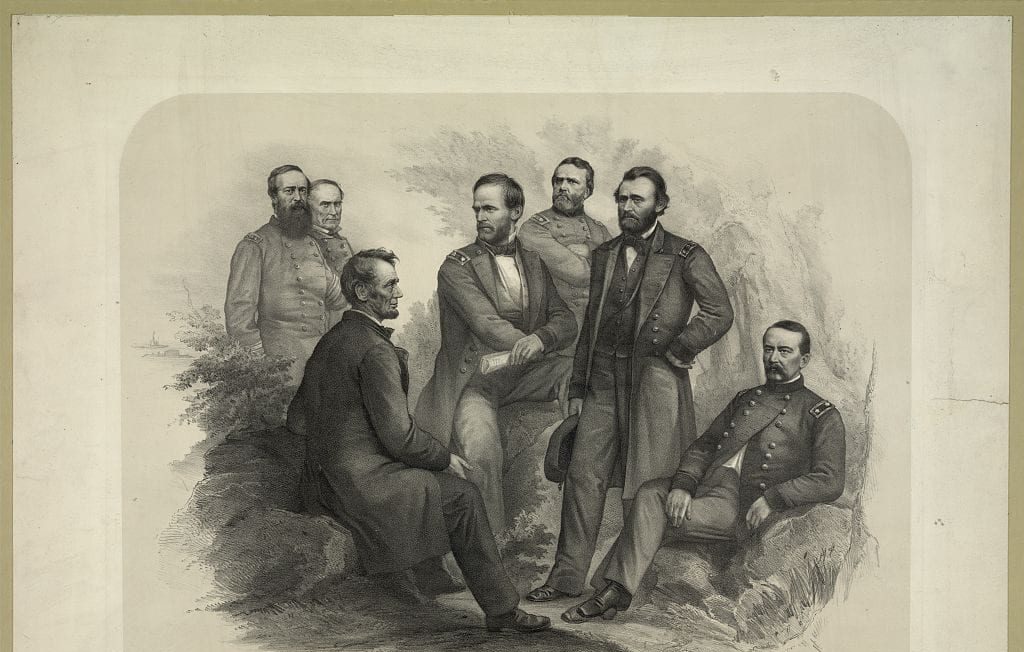

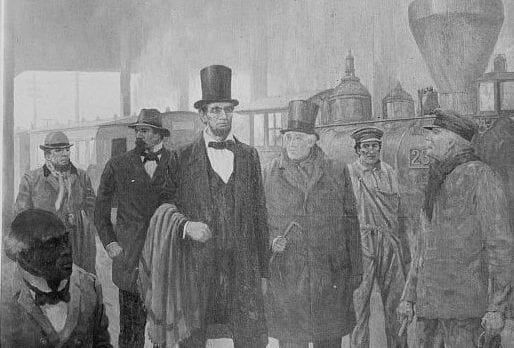

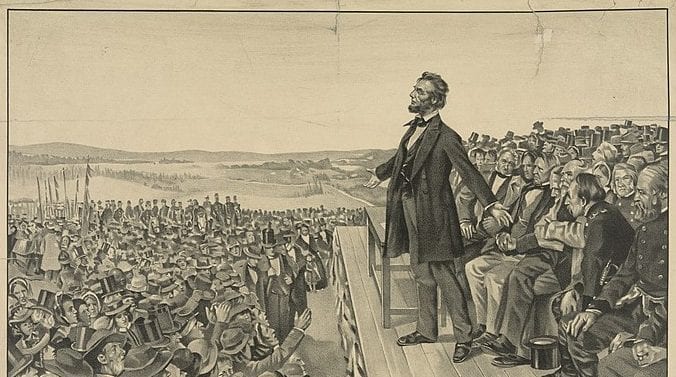

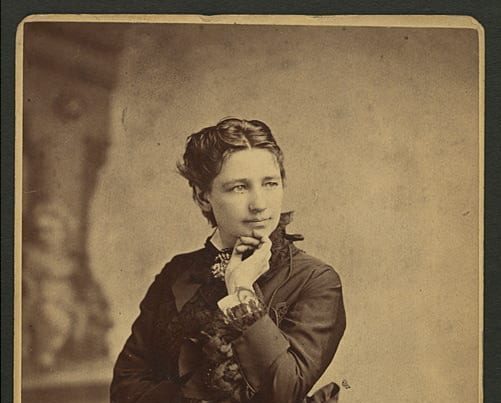

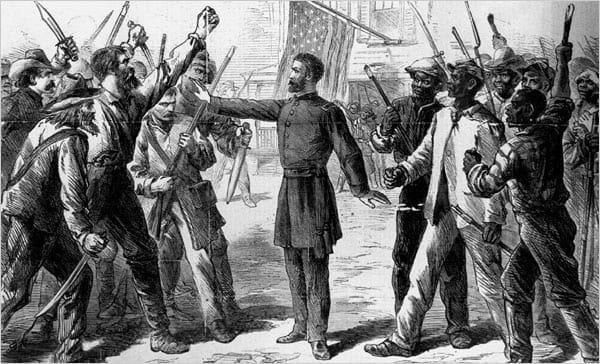

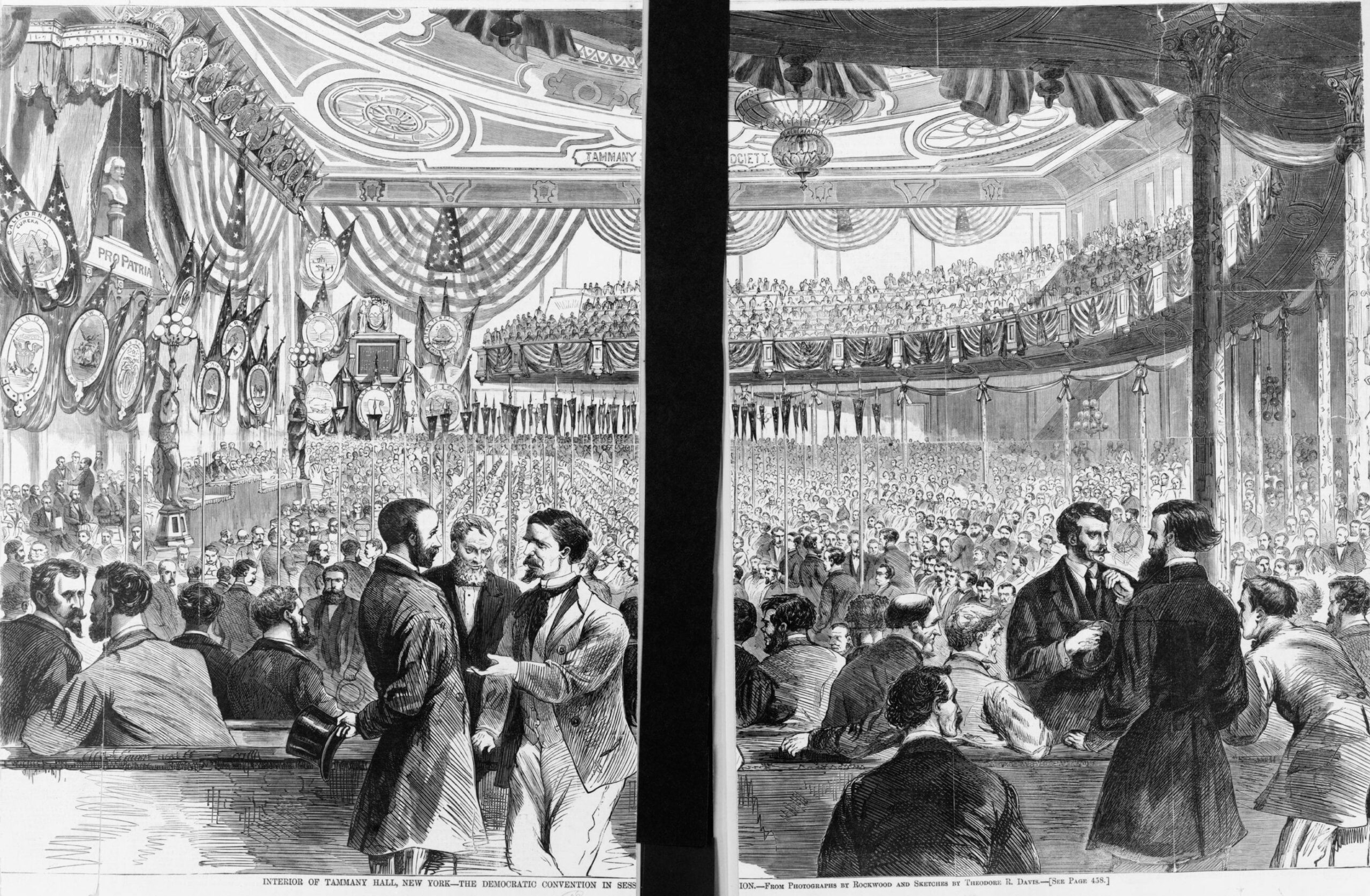

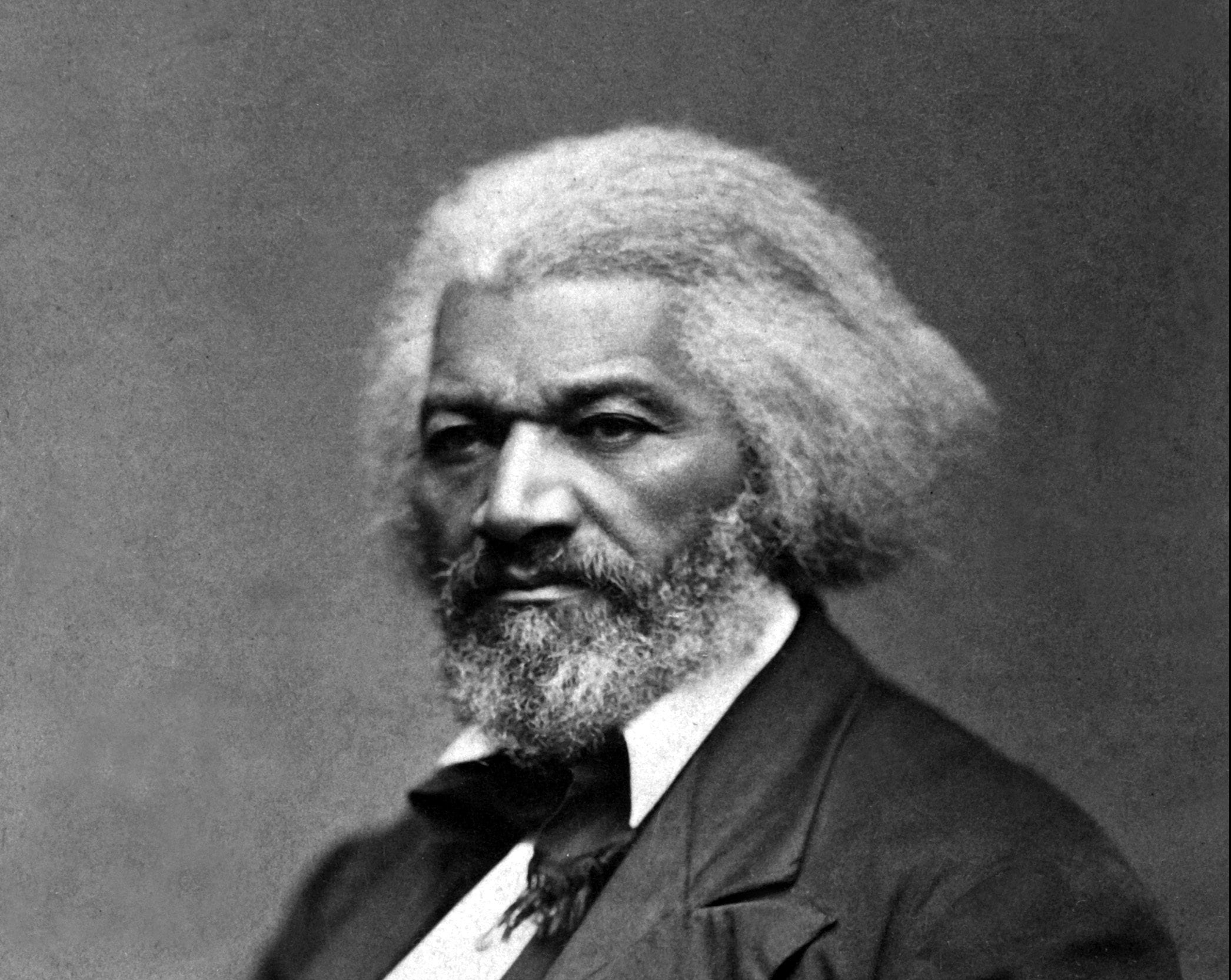

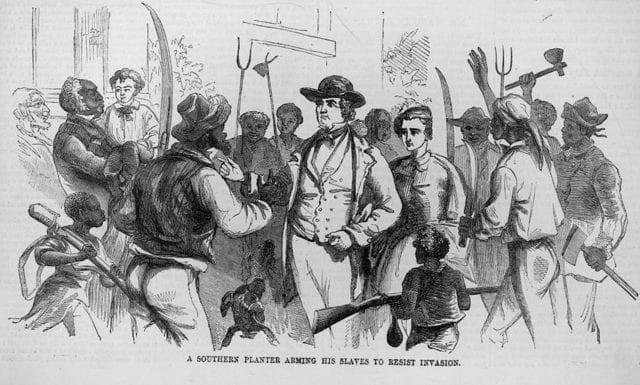

During Reconstruction (1865–1877) former Confederates sought to restore “home rule,” which meant returning to rule by the old slave owners and rebels. To achieve this end, they used small-scale political violence to intimidate and silence opponents, while counting on Northern exhaustion to eventually quell objections to civil rights violations. The Ku Klux Klan was a major force behind much of the violence. Federal efforts to stop Klan violence were not entirely successful given the unwillingness of southerners to take action against the Klan. Where federal arms were present, Republicans and freedmen could achieve political power and live in some security (see image A). Where these arms were not effective, both were endangered. Despite these unpromising circumstances, historian Eric Foner has concluded that federal efforts, especially in South Carolina, had by 1872 broken “the Klan’s back and produced a dramatic reduction in violence throughout the South.”

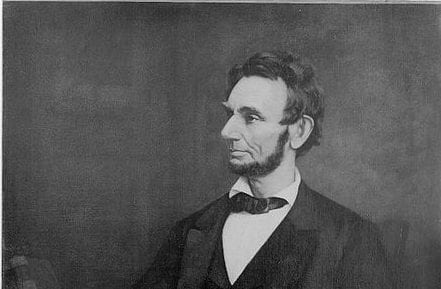

Nevertheless, a violent episode following Louisiana’s 1872 gubernatorial election demonstrates the nature of the political violence freedmen and Republicans faced in the South, and the difficulty constitutional government faced in taming it. The election had pitted a Republican, William Pitt Kellogg (1830-1912), against John McEnery (1833-1921), the candidate of a “Fusion” party (an alliance between Liberal Republicans in favor of home rule and Democrats willing to make limited reforms). Both sides claimed victory. Two slates of officials were appointed for such executive offices as sheriff. The conflict over the sheriff’s office and control of a courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana led to the Colfax Massacre, in which a force of white Democrats overpowered black Republicans and black State militia, murdering approximately 150, most after they surrendered. It was hardly the first such bloody massacre in Louisiana, but it was the largest.

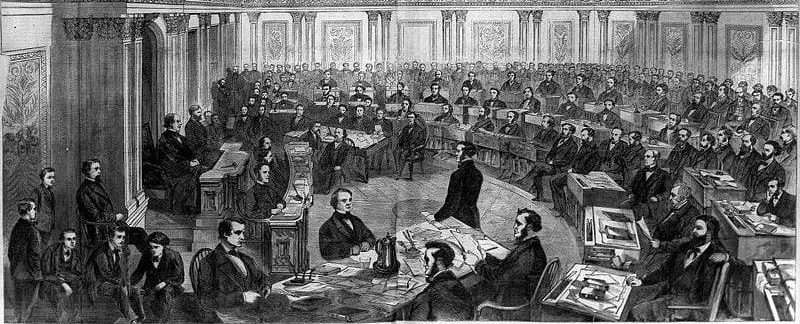

Below are two documents, one from the U.S. House of Representatives report on political violence in Louisiana generally and at Colfax specifically, the other from a New Orleans based Committee of 70, which wrote a report about the massacre from the perspective of the white desire for home rule. The Committee of 70 Report illustrates the nature of southern justice under home rule. In the case that grew out of the Colfax Massacre, United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the Supreme Court limited federal efforts to protect freedmen and Republicans in the South. This ruling was part of the impetus for the federal military withdrawal from the South.

Source: “Condition of the South,” Report Number 261, in Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-Third Congress (Washington D.C.: U.S. Printing Office, 1875), pp. 11–14, https://goo.gl/fsC5mu; Committee of 70, “History of The Riot at Colfax, Grant Parish, Louisiana, April 13th, 1873: With a Brief Sketch of the Trial of The Grant Parish Prisoners In The Circuit Court Of The United States” (New Orleans: Clark & Hofeline, 1874), 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10–11, 12, 13.

U.S. House of Representatives | Report on the Condition of the South

In the year 1868, the year of the presidential election, occurred six bloody and terrible massacres . . . .

The testimony shows that over two thousand persons were killed, wounded, and otherwise injured in that state within a few weeks prior to the presidential election; that half the State was overrun by violence; midnight raids, secret murders, and open riot kept the people in constant terror until the Republicans surrendered all claims, and then the election was carried by the democracy.[1] The parish of Orleans contained 29,910 voters, 15,020 black. In the spring of 1868 that parish gave 13,973 Republican votes; in the fall of 1869, it gave Grant 1,178, a falling off of 12,795 votes. Riots prevailed for weeks, sweeping the city of New Orleans, and filling it with scenes of blood, and Ku-Klux notices were scattered through the city, warning the colored men not to vote. In Caddo, there were 2,987 Republicans. In the spring of 1868 [Republicans] carried the parish. In the fall, they gave Grant one vote. Here also were bloody riots. But the most remarkable case is that of Saint Landry, a planting parish on the River Teche. Here the Republicans had a registered majority of 1,071 votes. In the spring of 1868 they carried the parish by 678. In the fall they gave Grant no vote – not one, while the Democrats cast 4,787, the full vote of the parish, for Seymour and Blair.[2]

Here occurred one of the bloodiest riots on record, in which the Ku-Klux killed and wounded over two hundred Republicans, hunting and chasing them for two days and nights, through fields and swamps. Thirteen captives were taken from the jail and shot. A pile of twenty-five dead bodies were found half buried in the woods. Having conquered the Republicans, killed and driven off the white leaders, the Ku-Klux captured the masses, marked them with badges of red flannel, enrolled them in clubs, led them to the polls, made them vote the Democratic ticket, and then gave them certificates of that fact.

In the year 1873 occurred the transaction known as the Colfax massacre, to which the committee directed special attention. . . . It seems to us there is no doubt as to the truth of the following narrative:

In March, 1873, Nash and Cagaburt claimed to be judge and sheriff of Grant Parish under commissions from Governor Warmouth.[3] After Governor Kellogg[4] succeeded Warmouth, their friends applied to him to renew their commissions. He refused, and commissioned Shaw as sheriff, and Register as judge. They went to the courthouse, which they found locked, and Shaw and the other parish officers entered it through the window. Six days after, hearing rumors of an armed invasion of the town to retake the courthouse, Shaw deputized, in his writing, from fifteen to eighteen men, mostly Negroes, to assist as his posse in holding the courthouse and keeping the peace. The next day, April 1st, a company of from 9 to 15 mounted men, headed by one Hudnot,[5] came into Colfax, some of them armed with guns; and on the same day one or two other small armed squads also came into town. This day no collision occurred.

April 2, a small body of armed white men rode into the town, and were met by a body of armed men, mostly colored, and exchanged shots, but no one was hurt.

These proceedings alarmed the colored people, and many of them, with their women and children, came to Colfax for refuge, perhaps a majority of the men being armed.

April 5, a band of armed whites went to the house of Jesse M. Kinney, a colored man, three miles from Colfax, and found him quietly engaged in making a fence. They shot him through the head and killed him. This seems to have been an unprovoked, wanton, and deliberate murder. This aroused the terror of the colored people. Rumors were also spread of threats made by them against the whites. April 7 the court was opened and adjourned. The alarm somewhat subsided and many colored people returned to their homes, the others maintaining an armed organization outside the town. April 12 the colored men threw up a small earthwork near the courthouse. Easter Sunday, April 13, a large body of whites rode into the town, and demanded of the colored men that they should give up their arms and yield possession of the courthouse. This demand not being yielded to, thirty minutes were given them to remove their women and children. The Negroes took refuge behind their earthwork, from which they were driven by an enfilading[6] fire from a cannon which the whites had. Part of them fled for refuge to the courthouse, which was a one-story brick building, which had formerly been a stable. The rest, leaving their arms, fled down the river to a strip of woods, where they were pursued, and many of them were overtaken and shot to death.

About sixty or seventy got into the courthouse. After some ineffectual firing on each side, the roof of the building was set fire to. When the roof was burning over their heads the Negroes held out the sleeve of a shirt and the leaf of a book as flags of truce. They were ordered to drop their arms. A number of them rushed unarmed from the blazing building, but were all captured. The number taken prisoners was about thirty-seven. They were kept till dark, when they were led out two by two, each two with a rank of mounted whites behind them, being told that they were to be taken a short distance and set at liberty. When all the ranks had been formed the word was given, and the Negroes were all shot. A few who were wounded, but not mortally, escaped by feigning death.

The bodies remained unburied till the next Tuesday, when they were buried by a deputy marshal from New Orleans. Fifty-nine dead bodies were found. They showed pistol-shot wounds, the great majority of them in the head, and most of them in the back of the head.

Two white men only were killed in the whole transaction, Hudnot the leader, and one Harris. . . .

[T]his deed [the Colfax Massacre] was without palliation or justification; it was deliberate, barbarous, cold-blooded murder. It must stand, like the massacre of Glencoe or St. Bartholomew,[7] a foul blot on the page of history.

Spread over all these years are a large number of murders and other acts of violence done for political ends. In reply to an inquiry of the committee, General Sheridan,[8] who is gathering careful statistics of the number of persons killed and wounded in Louisiana up to February 8, 1875, since 1866, on account of their political opinions, reports the number so far ascertained to be as follows:

Killed 2,141

Wounded 2,115

. . . .

Committee of 70 Report

Grant Parish lies on the North Bank of Red River, some three hundred and fifty miles from New Orleans. It was created by the legislature of 1869; . . . its population is about 5,000; the races are almost equal in numbers; the swamp land, which is a belt of low land that skirts the north bank of the river the entire length of the parish . . . is . . . divided into large plantations. To the north of this belt of low land, the character of the country changes, the land becomes rolling and is covered with pine forests, while the farms are smaller, and not near so productive. The large majority of the Negroes occupy and live in the low lands, upon the great plantation, while in the uplands the white race very largely preponderates.

Colfax – the parish seat – is a small village containing four or five dwelling houses, two or three stores, and perhaps a resident population of 75 or 100 persons. . . .

. . . In November, 1872, a general election was held in the State of Louisiana. The Republican party ran its straight ticket, headed by Wm. Pitt Kellogg. The other party, ran a ticket, at the head of which was John McEnery, and upon which were Democrats, Liberal Republicans and Reformers, and which was known as the “Fusion ticket.”[9]

After a spirited contest, remarkable for its peaceful character, the legal returns of the only legal officers of the election showed the triumph of the Fusion ticket by majorities ranging from 9,000 to 16,000 votes.

The order of Judge Durell,[10] the seizure of the State House by Federal soldiers, the assemblage by violence of a legislature at whose doors were armed Federal soldiers . . . and the inauguration of Wm. Pitt Kellogg, under the shadow of Federal bayonets soon followed.[11] Meanwhile John McEnery had been inaugurated Governor, and the oath of office administered to him in Lafayette Square, in the presence of 30,000 people, and amidst the greatest demonstrations of popular joy. The Fusion legislature was meeting . . . in regular and constitutional session. The officers elected to fill the various offices in the Districts and Parishes throughout the State had been commissioned by Governor Warmoth [the former Governor], on the 4th day of December 1872. Gov. McEnery also, believing himself the rightful Governor of the State, made such appointments throughout the State as were required by existing laws. . . .

Thus it will be seen that there were two Governors, two Legislatures, and two sets of officers throughout the entire State. . . .

Thus it will be seen, that throughout the length and breadth of the State anarchy, confusion and disorder reigned, and the utmost bitterness of feeling between the partisans of the rival governments prevailed.

This state of feeling and disorder had extended also to Grant Parish. At the November election, Alphonse Cazabat and Columbus C. Nash had been the Fusion candidates for the offices of Parish Judge and Sheriff. The election resulted in their success by majorities averaging from two hundred and fifty to three hundred votes, out of a full vote of near one thousand. They were commissioned by Gov. Warmouth on the 4th day of December, 1872, and toward the latter part of that month entered upon their official duties, and discharged them up to the 25th of March, 1873. Upon the same ticket with them, James W. Hadnot had been elected to represent Grant Parish in the Legislature, and had been meeting with the McEnery body . . .

. . . But Mr. Kellogg had learned that bayonets were stronger than popular will; had learned to look with contempt upon the idea of local self-government, and . . . [he] commissioned in absolute defiance of popular will, R. C. Register, Parish Judge, and Daniel Shaw as Sheriff. About the 23d of March, Register, [and Kellogg’s other appointees] . . . arrived at Colfax.

It will be borne in mind that Judge Cazabat and Sheriff Nash, up to that time, had been in full and complete possession of their offices, and were still exercising their functions. On that day, however, Register and Shaw took forcible and violent possession of the court-house. . . . There was no one to resist them. That same night, for reasons best known to themselves, they began to summon armed Negroes into Colfax. At first Shaw, acting under the order of Register, pretended to summon these Negroes as a sheriff’s posse. But within five or six days Shaw’s authority was set at naught and no longer regarded, and he himself detained in Colfax, watched and guarded, virtually a prisoner; and when he attempted to escape, was pursued and brought back under guard. . . .

Thereafter the assemblage increased in Colfax, and from the 24th of March to April 13th the crowd of Negroes in Colfax was variously estimated at from 150 to 400 men. After the deposition of Sheriff Shaw’s authority, the assemblage assumed a semi-military character. Three Captains were elected, and lieutenants, sergeants and corporals were appointed; men were regularly enrolled. . . . The Negroes were armed with shot-guns and Enfield rifles, and seizing upon an old steam pipe they cut it up, and by plugging one end of each piece and drilling vents, they improvised and mounted three cannon. They constructed a line of earth-works, some 300 yards in length and from 2 ½ to 4 feet high. Drilling was regularly kept up by Ward, Flowers and Levi Allen, all of whom had been soldiers of the United States Army. Guards were mounted and pickets posted, while mounted squads scouted the neighboring country. No white citizens were permitted to pass into Colfax.

In the meantime the white citizens of the Parish were filled with apprehension and alarm. A mass meeting was called for April 1st. It was proposed by Hadnot . . . and others that a meeting be held at Colfax; that the colored people be invited, and an attempt made to compromise the existing difficulties. . . .

In the meanwhile, affairs grew more alarming – Rapine, riot and outrage held high sway in Colfax. . . .

Judge Rutland and family had left the town early in the beginning of the troubles, having been obliged to leave his house and effects unguarded.

On the night of the 4th of April, Flowers, a little sleek, black Negro – a school master – at the head of a band of Negroes, broke open the house, plundered it, broke open and threw on the gallery of the house the coffin, containing the body of Judge Rutlaud’s child, rifled trunks, armoirs and bureaus, carried away all articles of value, and then . . . spent the night in riot and debauch. . . .

Over forty families of white people left their homes, and taking their household goods, fled twenty or thirty miles into the interior. It is worth note that of the nine men recently tried in the U. S. Circuit Court, four of them with their families were among these refugees, and the day of the fight were over twenty miles away from Colfax. This fact was shown by 12 or 14 witnesses, and yet the three embittered and prejudiced Negroes on the jury, persisted in declaring for their guilt. . . .

The most terrible and alarming threats of murder and rapine were made by the Negroes, and borne to the ears of the whites and terror, uncertainty and lawlessness prevailed from one end of the Parish to the other. . . .

During the week prior to April 13th, C. C. Nash, the duly elected, commissioned and acting sheriff of Grant parish was busy summoning a posse of men to retake the court-house and put down the lawlessness that had filled the parish with terror and alarm.

On Sunday, April 13th, he found himself at the head of about 150 armed men, four miles northwest of Colfax. . . . Besides his posse of mounted men, he had a small piece of artillery mounted on wagon wheels, and to fit which he had obtained some oblong slugs of iron. Halting his men, he advanced . . ., under a flag of truce, and asked a colored man – John Miles – whom he there met, who commanded in Colfax. He was told “Lev Allen is in command.” He then said, “Go and tell Lev to come here, that I want to see him.” Miles obeyed, and soon Lev Allen and a few other Negroes came out to where Nash was. From Miles’s testimony we learn that Allen acknowledged he was in command; that Nash told him he had come to retake the Court House; that he had force enough to accomplish it, and advised him that he had better disperse his men, and assured him that none of them would be molested. Allen peremptorily refused to disperse his men, and informed Nash that he and his men intended to fight to the last.

Nash then told him to remove all the women and children, and that half an hour would be granted for that purpose; and he and Allen separated, the former returning to his men, and the latter issuing orders for the women and children to leave the quarters and town of Colfax.

Up to this hour every effort at pacification had been made, and each time the advance had been made by the whites. . . .

About 12 o’clock, . . . the Negroes opened fire upon his force from the two pieces of improvised cannon which had been posted there. The whites returned the fire with small arms, and the Negroes retired to within their line of works near the Court House, and, lying down behind them, kept up a brisk fire with their shot-guns, rifles and pistols. The whites fired several shots from their cannon, which seemed to have done no harm whatever. Affairs continued thus for two hours, when about 2 P.M., the force under Nash, having secured a position for their cannon which commanded the inside of the line of works, opened fire upon the Negroes, who, finding their position untenable, retreated in all directions. Perhaps one hundred and fifty retreated into the woods and fields, and about one hundred took refuge in the Court House. Nash then opened fire upon that building, and one or two shots seemed to have struck its walls, without material damage. Up to this time no blood had been shed.

At this juncture the Court House was set on fire. It is doubtful as to how the fire originated. Some of the Negro witnesses testify that it was fired by combustible matter projected from the cannon, while others assert that it was fired by a Negro prisoner, sent on purpose by the whites. At all events, the building was in flames when two white flags were displayed from the windows.

Instantly, the firing ceased. Mr. James W. Hadnot and Mr. Harris – unarmed, and with hands raised to show that they were unarmed – approached the Court House, calling upon the Negroes to throw down their arms, and that they would not be troubled. Approaching to within ten or fifteen feet of the Court House, these gentlemen were met by a volley from the Negroes, who by this time were coming out of the burning building, and both fell, mortally wounded. The whites – exasperated beyond endurance at the cowardly and treacherous murder of their comrades, thus lured to their death by the false flag of truce held out by the Negroes – closed upon them and slaughtered a large majority of them. The Court House was entirely destroyed, together with its books and records. Sixty-four Negroes were killed and wounded, the loss of the whites being four wounded and three killed. . . .

That excesses were committed by the outraged and exasperated whites, there can be no doubt. But let it be remembered that they had appealed for aid, and none came; that they tried four times to avoid bloodshed, and without avail; that civil government in the State seemed wholly subverted; that their families were fleeing in terror from their homes; that rapine, and pillage and lawlessness held high revel, and made their lives, their property, and all they held dear, totally insecure. And finally, let it be remembered that, in the heat of the fight, they saw two prominent citizens, their comrades, go upon an errand of peace, summoned by flags of truce displayed by the Negroes, unarmed, and with words of peace upon their lips, shot down, killed by the very persons they wished to save, and by the very hands that held the white flags of peace! . . .

In October, 1873, E. J. Cruikshank, A. C. Lewis, W. D. Irwin, John P. Hadnot, Denis Lemoine, Prudhomme Lemoine, A. P. Gibbons and Clement Penn were arrested and brought to New Orleans, and lodged in the Parish prison. . . .

We deplore in common with all good citizens, the bloody affair at Colfax. We can view it in no other light than affording another evidence of the results of the misrule and oppression of the Southern States at the hands of the Federal power.

It has its lesson to the Negro and to the white.

It teaches the former what he may expect, if in obedience to the devilish teachings of the Radical emissary,[12] he arrays himself in hostility to the whites of the South.

It teaches the latter that acts of violence, no matter what the provocation, are construed into hostility and hatred of the National Government, and retards [sic] the day of conservative triumph.

It should teach both that their interests, their homes and destiny being identical, they should cultivate assiduously amicable relations the one with the other, and be co-laborers in the noble work of regenerating and restoring our once happy State to its pristine position of power and prosperity.

- 1. The Democratic Party.

- 2. Horatio Seymour (1810-1886) and Francis Preston Blair (1791-1876) were the Democratic candidates for President and Vice-President in 1868.

- 3. Henry Clay Warmouth (1842–1931), a lawyer and Union officer in the Civil War, was born in Illinois but came to Louisiana when appointed judge of the Department of the Gulf Provost Court. A Republican, he was elected governor in 1868 and allied himself with the pro-conciliation, Liberal Republican branch of the party.

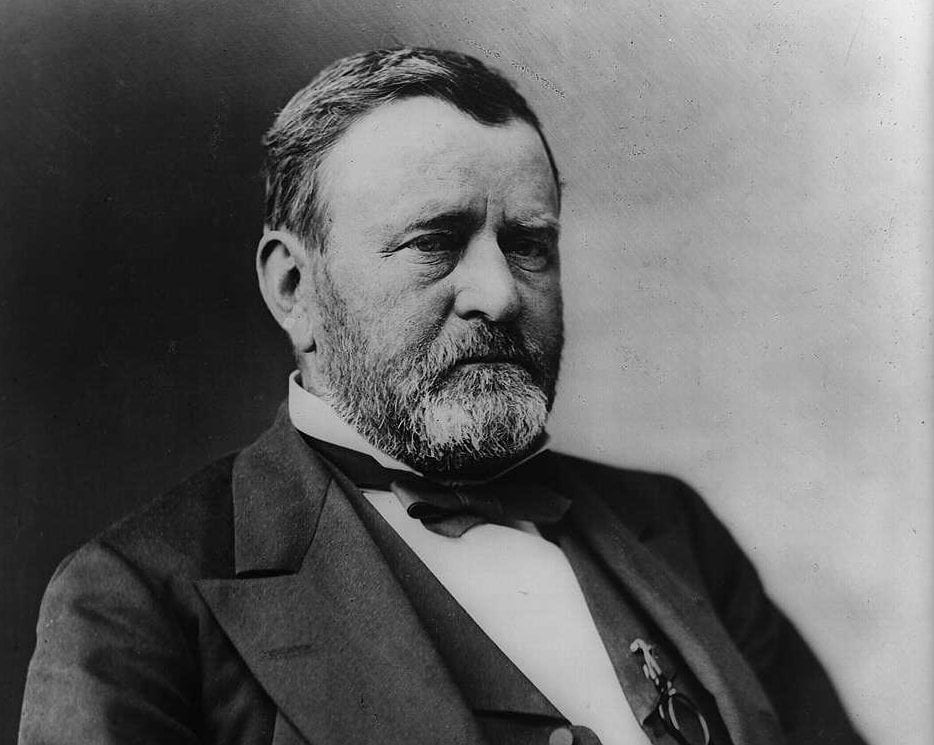

- 4. Kellogg – a native of Vermont, lawyer, judge, and Union officer – was collector of the Port of New Orleans from 1865 to 1868. A Radical Republican, he ran against Democrat John McEnery in the gubernatorial election of in 1872. The Warmouth-controlled State Returning Board declared McEnery the winner, while a federal board decided Kellogg had won. Kellogg was seated only after President Grant, in September 1873, issued an executive order declaring him the legal governor.

- 5. This was James W. Hadnot, according to a memorial erected by the white citizens of Colfax in 1921 that calls Hadnot and Sidney Harris (mentioned later in the excerpt) “Heroes” who fell in the “Colfax Riot.”

- 6. a sweeping volley

- 7. The Massacre of Glencoe was a massacre of Scottish highlanders by British forces in 1692. The Bartholomew Massacre was a massacre of French Huguenots (Protestants) by Catholics in 1572.

- 8. General Phillip Sheridan (1831-1888), Union cavalry general and loyal subordinate to General Grant during the Civil War.

- 9. A “Fusion” namely of Democrats and anti-Grant Liberal Republicans

- 10. Edward Henry Durell (1810 – 1887) was a New Orleans lawyer and Unionist who had opposed secession. He was appointed US District Judge for Louisiana in 1863.

- 11. Union law-enforcement and military forces judged the Fusion victory had been won more through corruption and intimidation than through legitimate means, so the legal and military authorities supported the Republican candidate as the winner.

- 12. Republicans from the North or carpetbaggers, as they came to be called.

Minor v. Happersett

March 29, 1875

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.