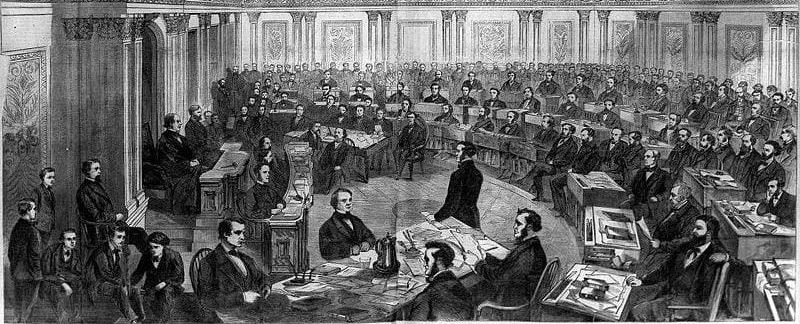

Introduction

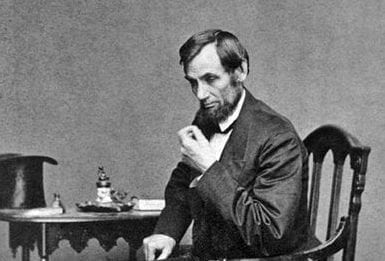

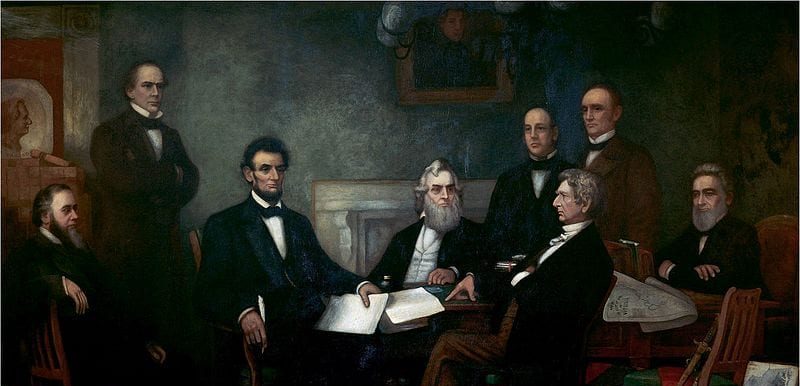

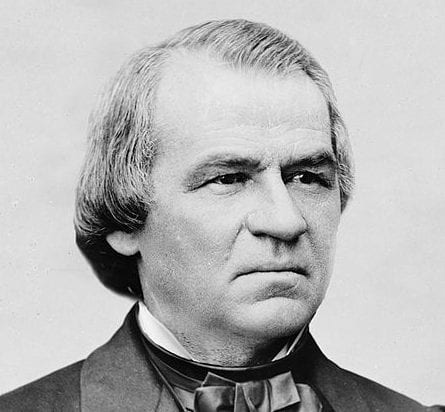

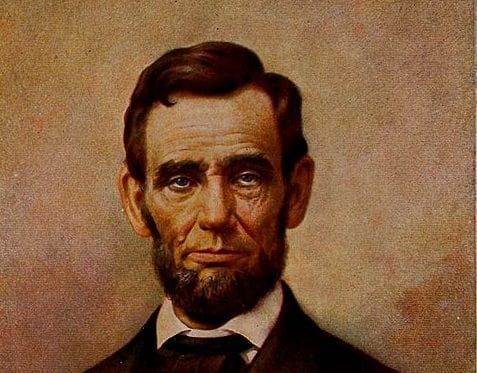

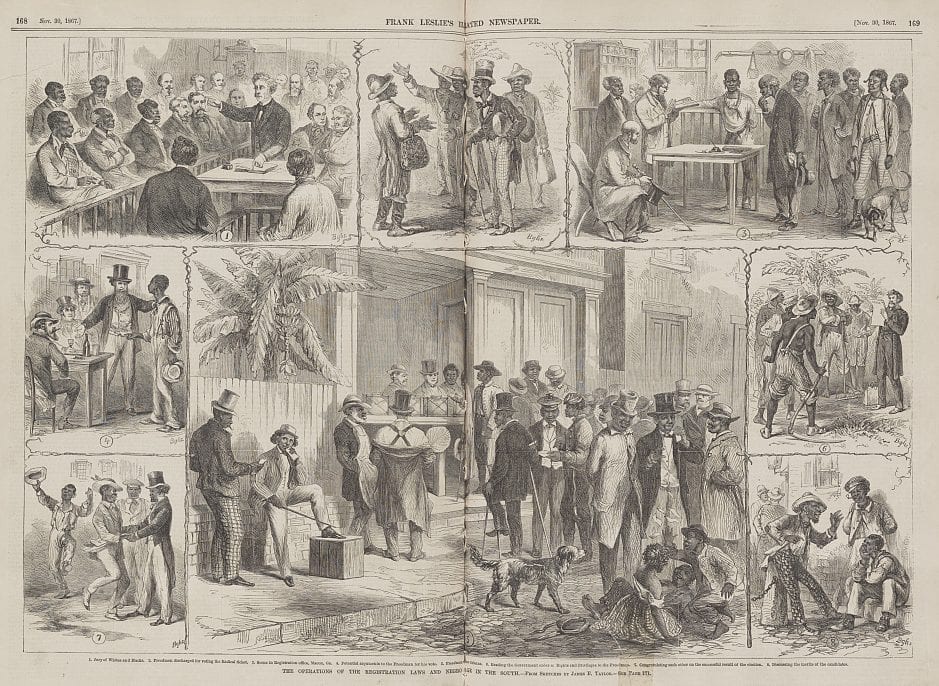

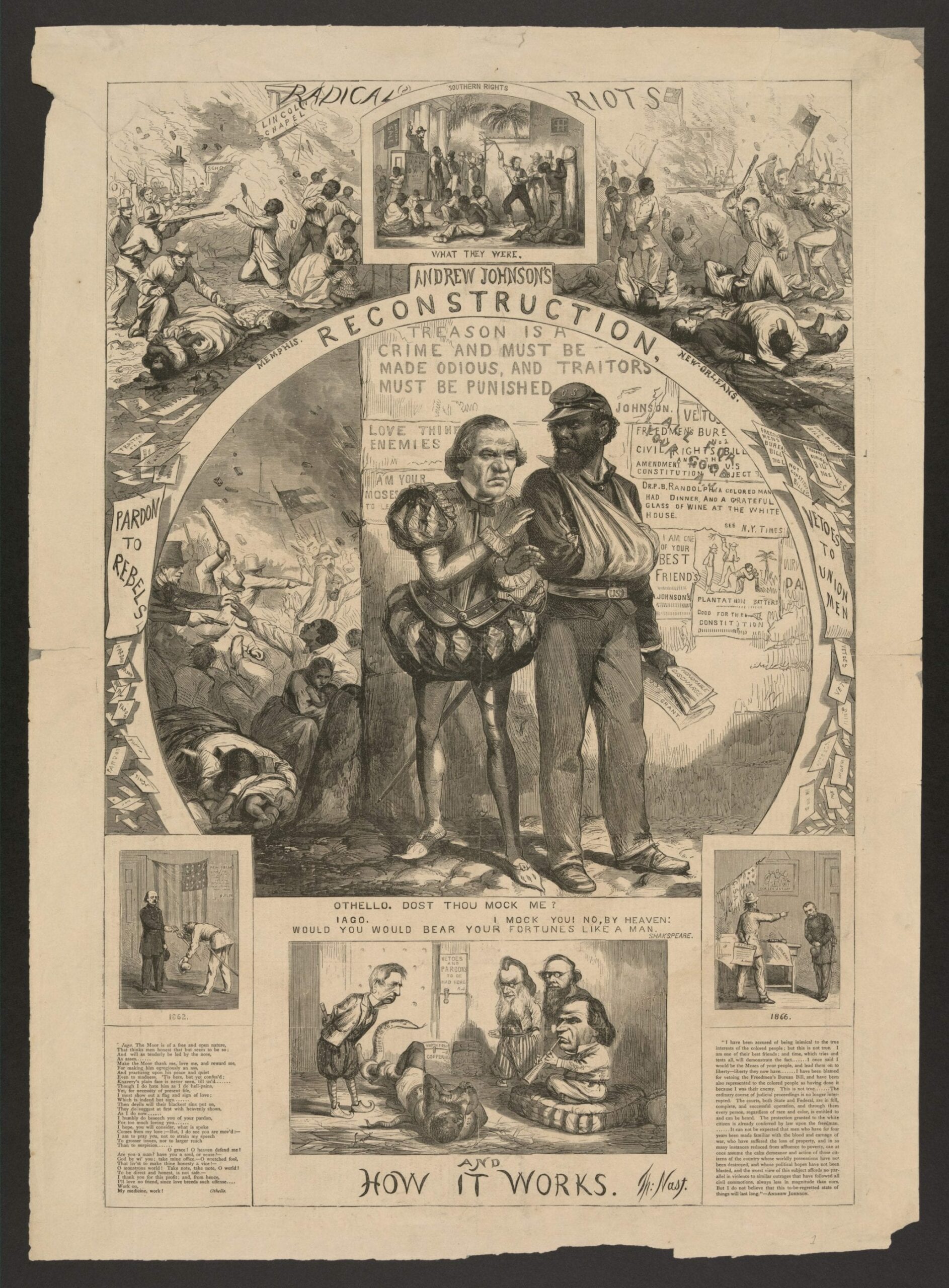

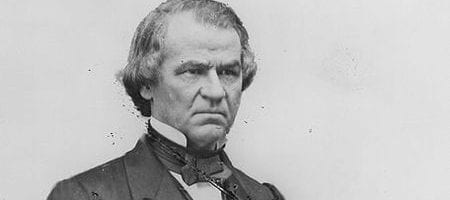

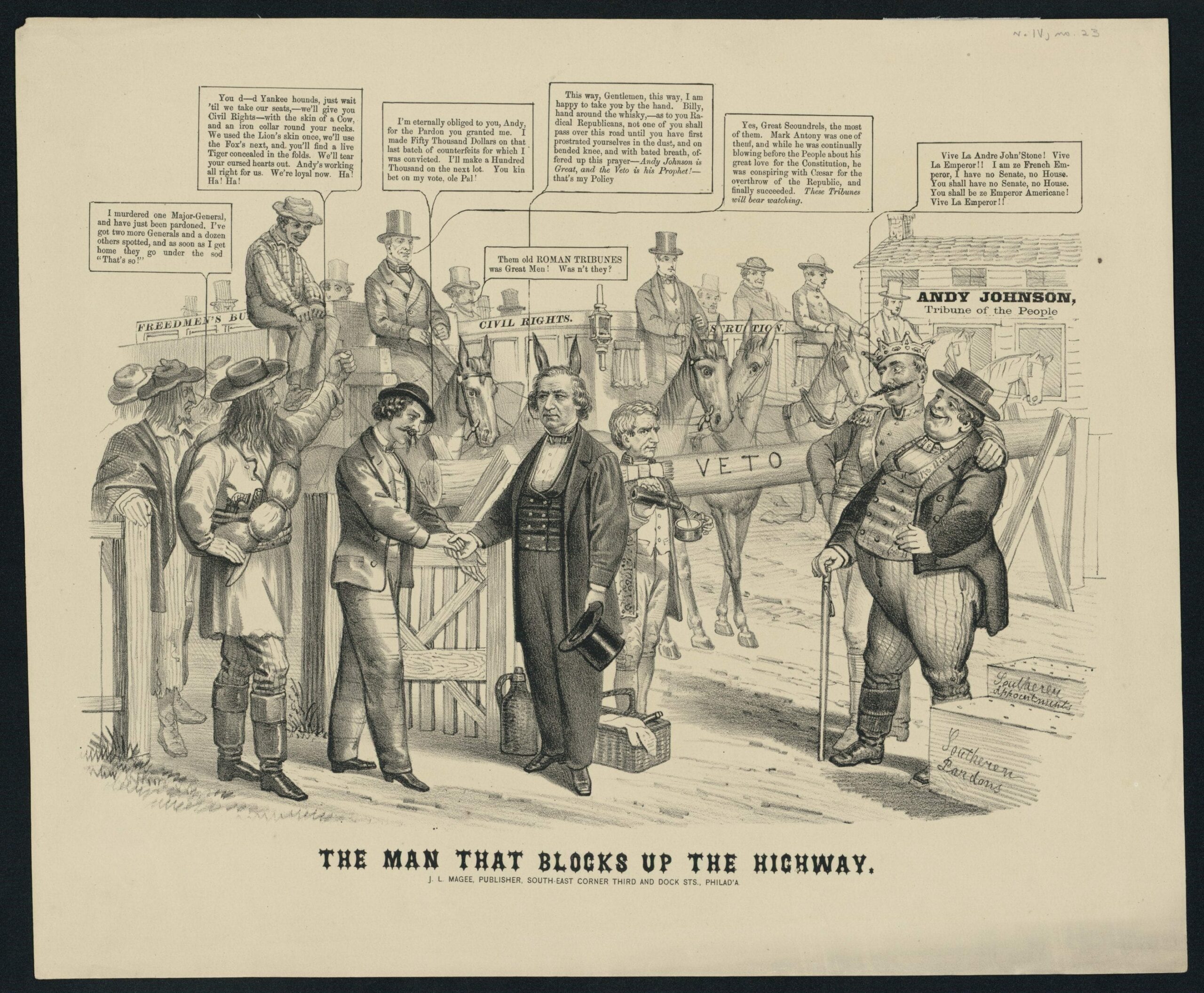

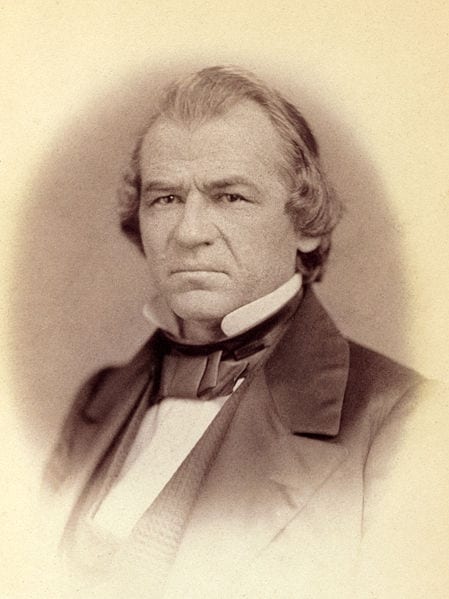

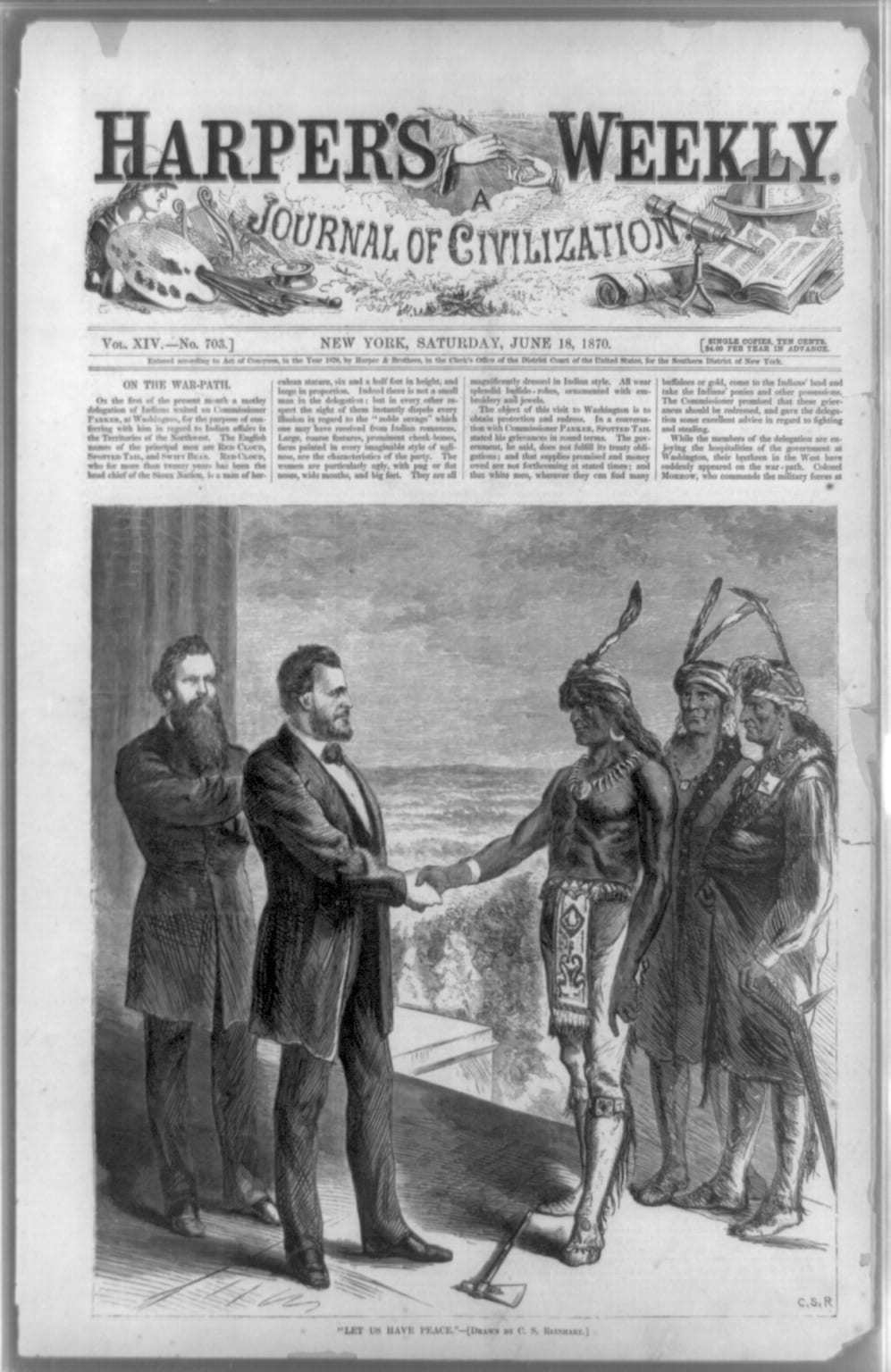

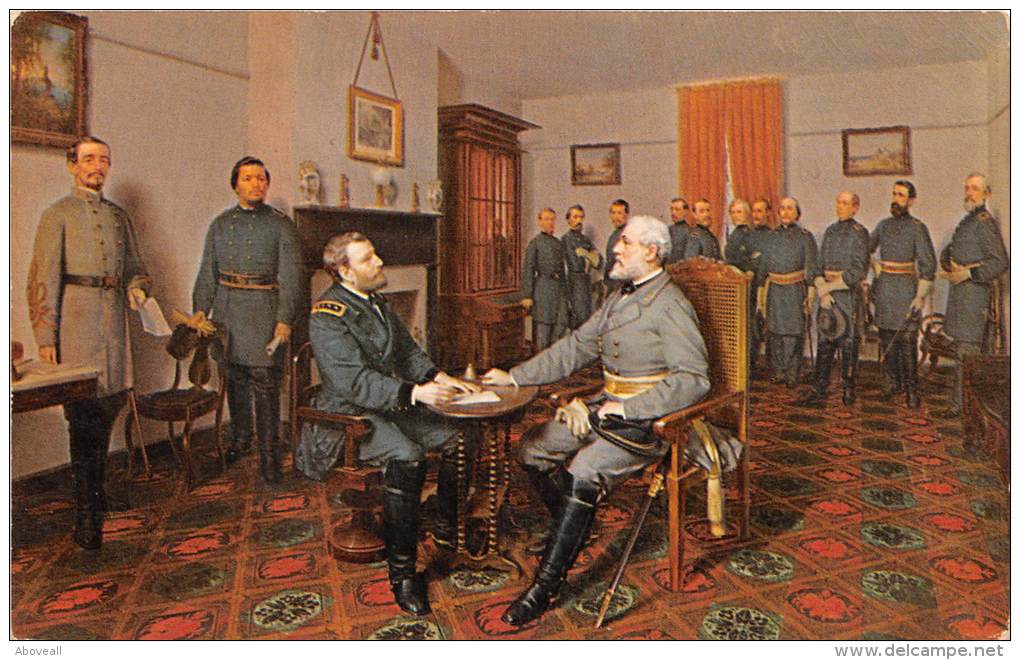

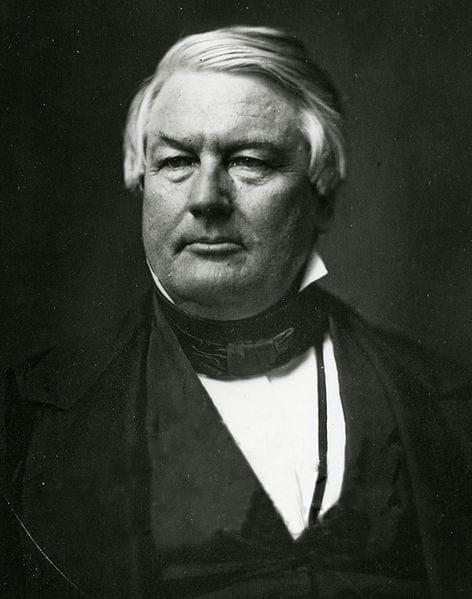

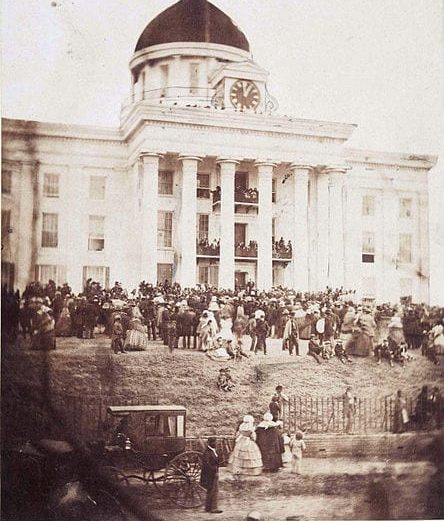

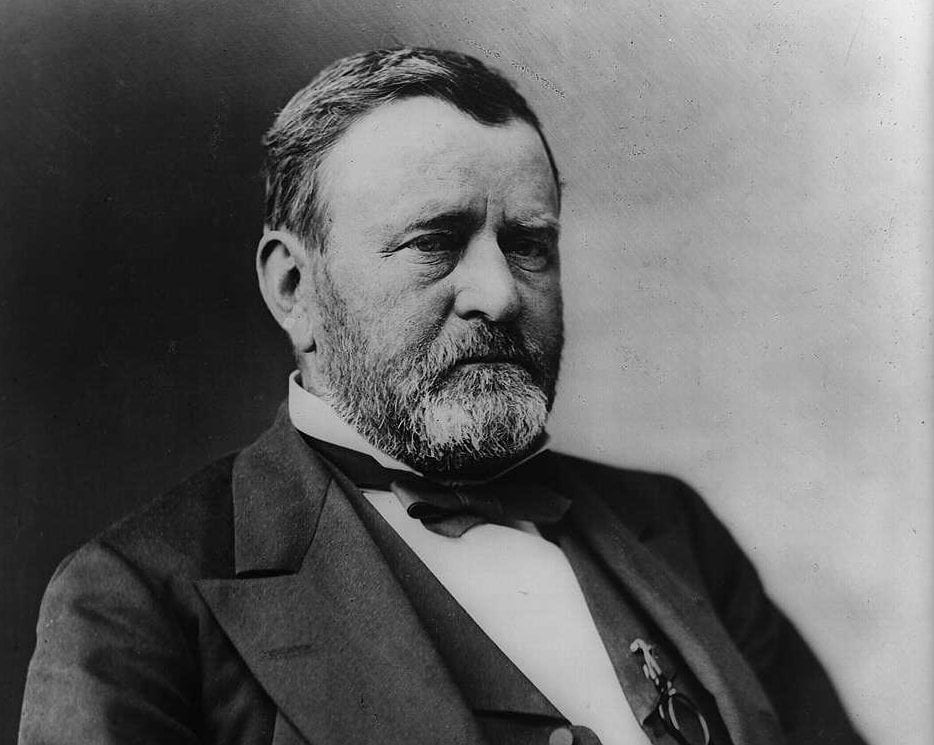

In his First Annual Address, President Andrew Johnson seemed to think that restoration of Southern states was by and large completed. Constitutional conventions had been held. Elections were conducted. New governments met. All, according to Johnson, seemed to be going about as well as could be hoped. No less an authority than General Ulysses S. Grant, the Union’s victorious general, concluded that “the mass of thinking men in the South accept the present situation of affairs in good faith.” Yet doubts about Johnson’s understanding of the state of things lingered: there was genuine disagreement about what the Southerners were thinking and doing and about what could be realistically hoped for. Northern Republicans saw Black Codes passed, rebels elected to offices high and low, and Union men attacked in the South and worried that the situation was still a low-level rebellion. An adequate evaluation of Johnson’s policy of quick restoration depended on accurate knowledge of what was going on in the South.

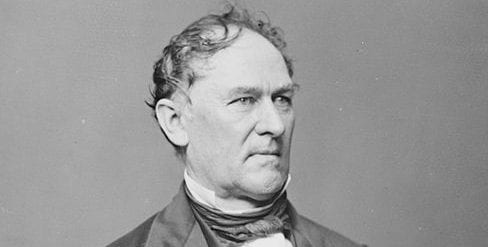

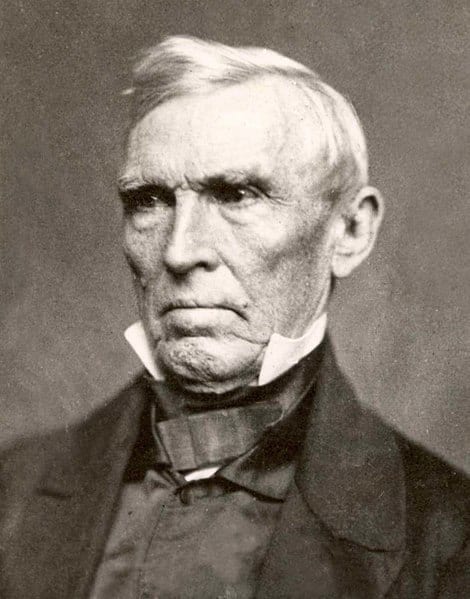

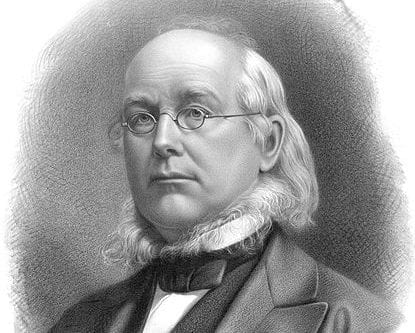

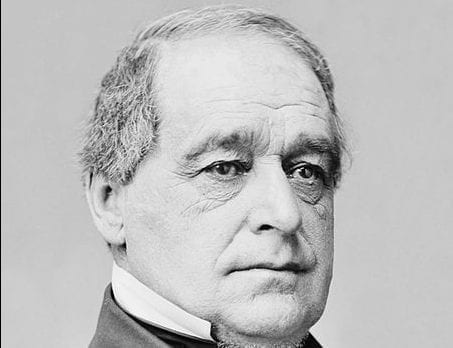

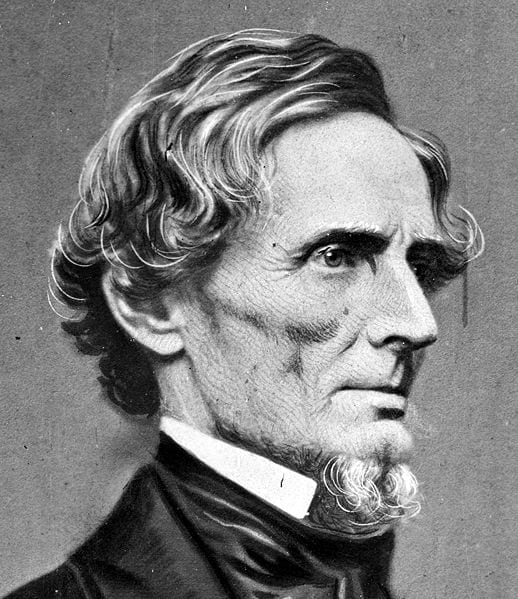

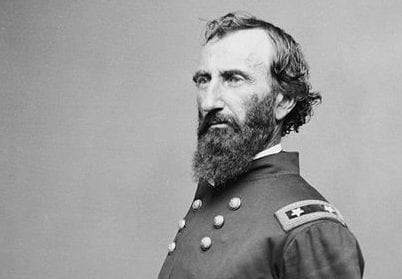

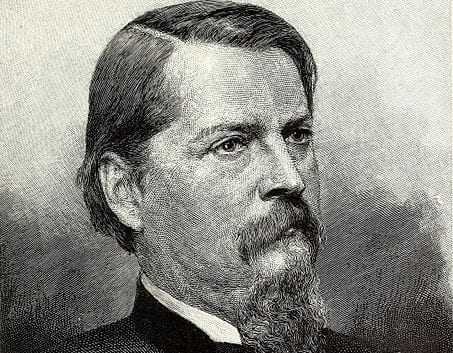

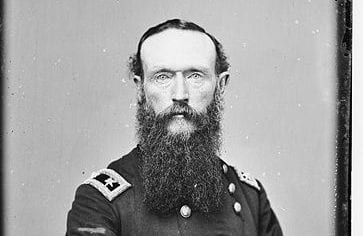

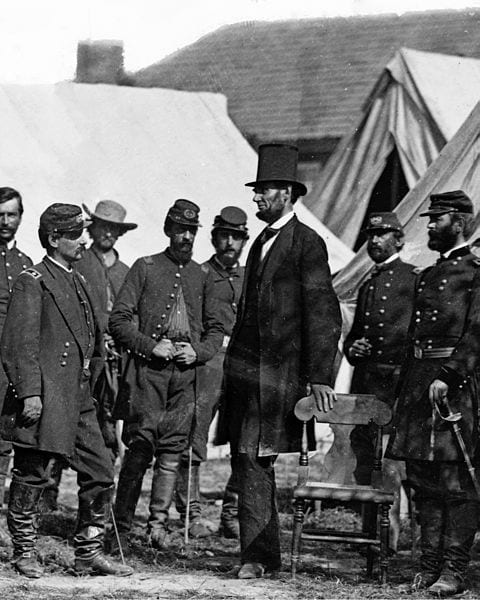

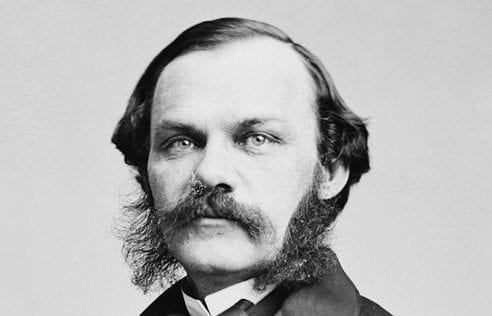

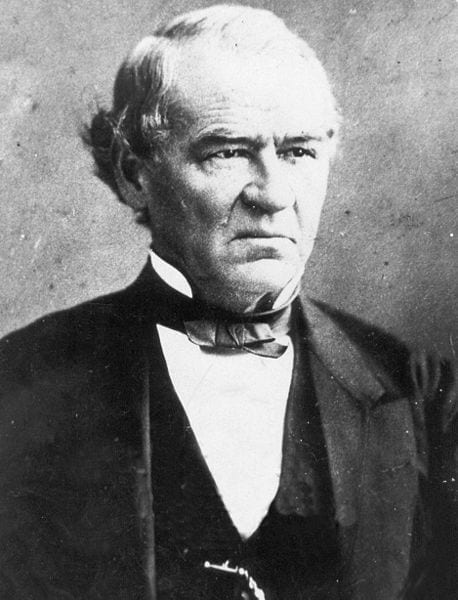

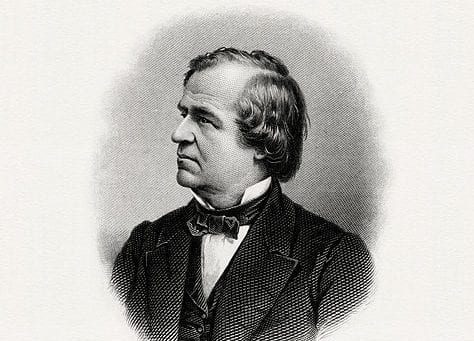

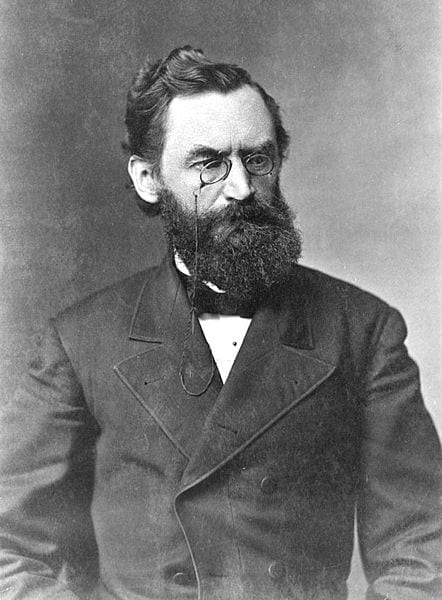

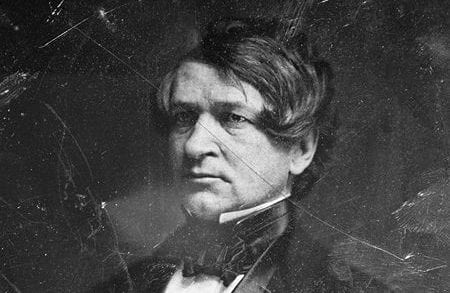

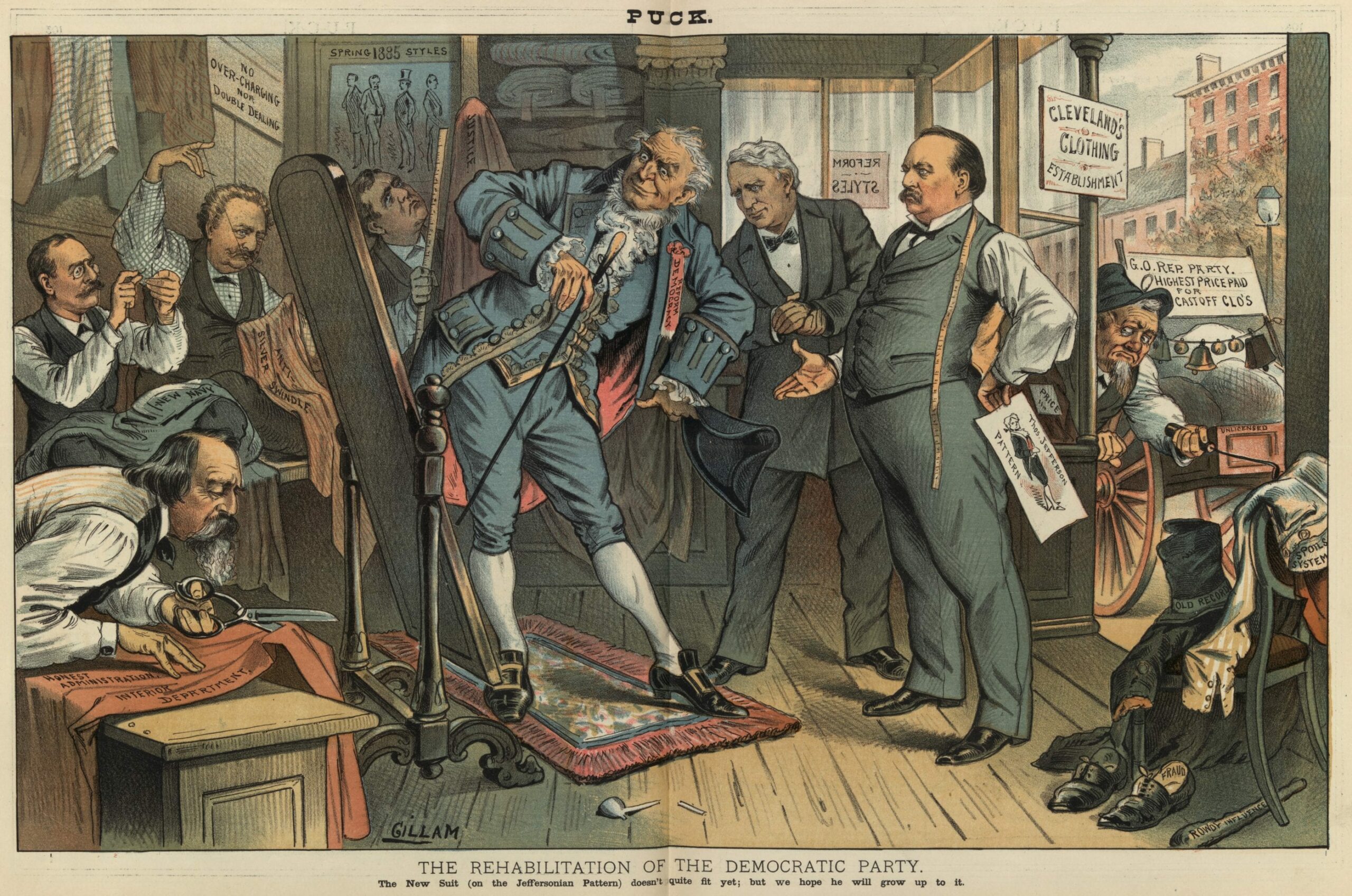

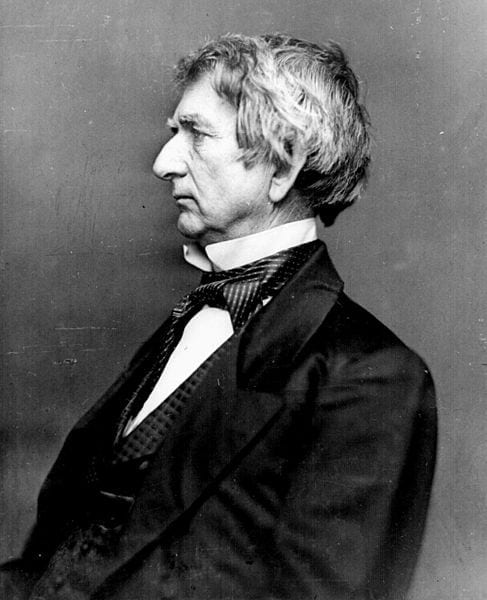

Enter Carl Schurz (1829-1908), a German immigrant and Union general from Missouri, who would later be elected senator. Johnson sent Schurz on a fact-finding mission to the South during the summer of 1865. Schurz fell out with Johnson along the way, as Johnson adopted a policy of relatively easy restoration for Southern states and allowed several states to organize their own militias. Schurz opposed these policies openly. Schurz delivered his report to the U.S. Senate, setting the stage for the criticisms of Johnson’s plans and for the rise of an alternative mode of reconstruction that tried to hold states to a much higher standard.

Source: Carl Schurz, “Report on the Condition of the South,” in Speeches, Correspondences, and Political Papers of Carl Schurz, Edited by Frederic Bancroft (New York: G. T. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), Volume I, 279, 281–82, 283–86, 289–90, 292–93, 302–04, 306, 309, 311, 327–28, 329, 331, 332–33, 343–44, 346–47, 354, 356–358, 359.

. . . You did me the honor of selecting me for a mission to the States lately in rebellion, for the purpose of inquiring into the existing condition of things, of laying before you whatever information of importance I might gather, and of suggesting to you such measures as my observations would lead me to believe advisable. . . .1

Condition of Things Immediately After the Close of the War

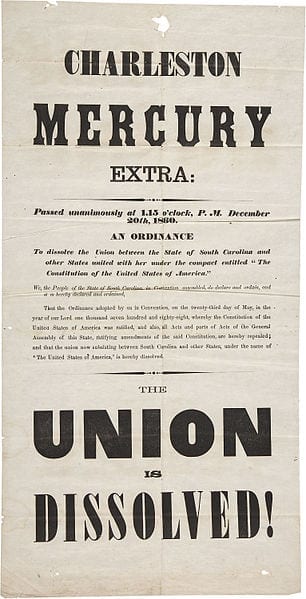

In the development of the popular spirit in the South since the close of the war two well-marked periods can be distinguished. The first commences with the sudden collapse of the confederacy and the dispersion of its armies, and the second with the first proclamation indicating the “reconstruction policy” of the Government. Of the first period I can state the characteristic features only from the accounts I received partly from Unionists who were then living in the South, partly from persons that had participated in the rebellion. When the news of Lee’s and Johnston’s surrenders burst upon the southern country the general consternation was extreme. People held their breath, indulging in the wildest apprehensions as to what was now to come. Men who had occupied positions under the Confederate Government, or were otherwise compromised in the rebellion, ran before the Federal columns as they advanced and spread out to occupy the country, from village to village, from plantation to plantation hardly knowing whether they wanted to escape or not. Others remained at their homes, yielding themselves up to their fate. . . .

Such was, according to the accounts I received, the character of that first period. The worst apprehensions were gradually relieved as day after day went by without bringing the disasters and inflictions which had been vaguely anticipated, until at last the appearance of the North Carolina proclamation2 substituted new hopes for them. The development of this second period I was called upon to observe on the spot, and it forms the main subject of this report.

Returning Loyalty

. . . The white people at large being, under certain conditions, charged with taking the preliminaries of “reconstruction” into their hands, the success of the experiment depends upon the spirit and attitude of those who either attached themselves to the secession cause from the beginning, or, entertaining originally the opposite views, at least followed its fortunes from the time that their States had declared their separation from the Union.

The first Southern men of this class with whom I came into contact immediately after my arrival in South Carolina expressed their sentiments almost literally in the following language: “We acknowledge ourselves beaten, and we are ready to submit to the results of the war. The war has practically decided that no State shall secede and that the slaves are emancipated. We cannot be expected at once to give up our principles and convictions of right, but we accept facts as they are, and desire to be reinstated as soon as possible in the enjoyment and exercise of our political rights.” This declaration was repeated to me hundreds of times in every State I visited, with some variations of language, according to the different ways of thinking or the frankness or reserve of the different speakers. . . .

Upon the ground of these declarations, and other evidence gathered in the course of my observations, I may group the Southern people into four classes, each of which exercises an influence upon the development of things in that section:

- Those who, although having yielded submission to the National Government only when obliged to do so, have a clear perception of the irreversible changes produced by the war, and honestly endeavor to accommodate themselves to the new order of things. Many of them are not free from traditional prejudices but open to conviction, and may be expected to act in good faith whatever they do. This class is composed, in its majority, of persons of mature age – planters, merchants, and professional men; some of them are active in the reconstruction movement, but boldness and energy are, with a few individual exceptions, not among their distinguishing qualities.

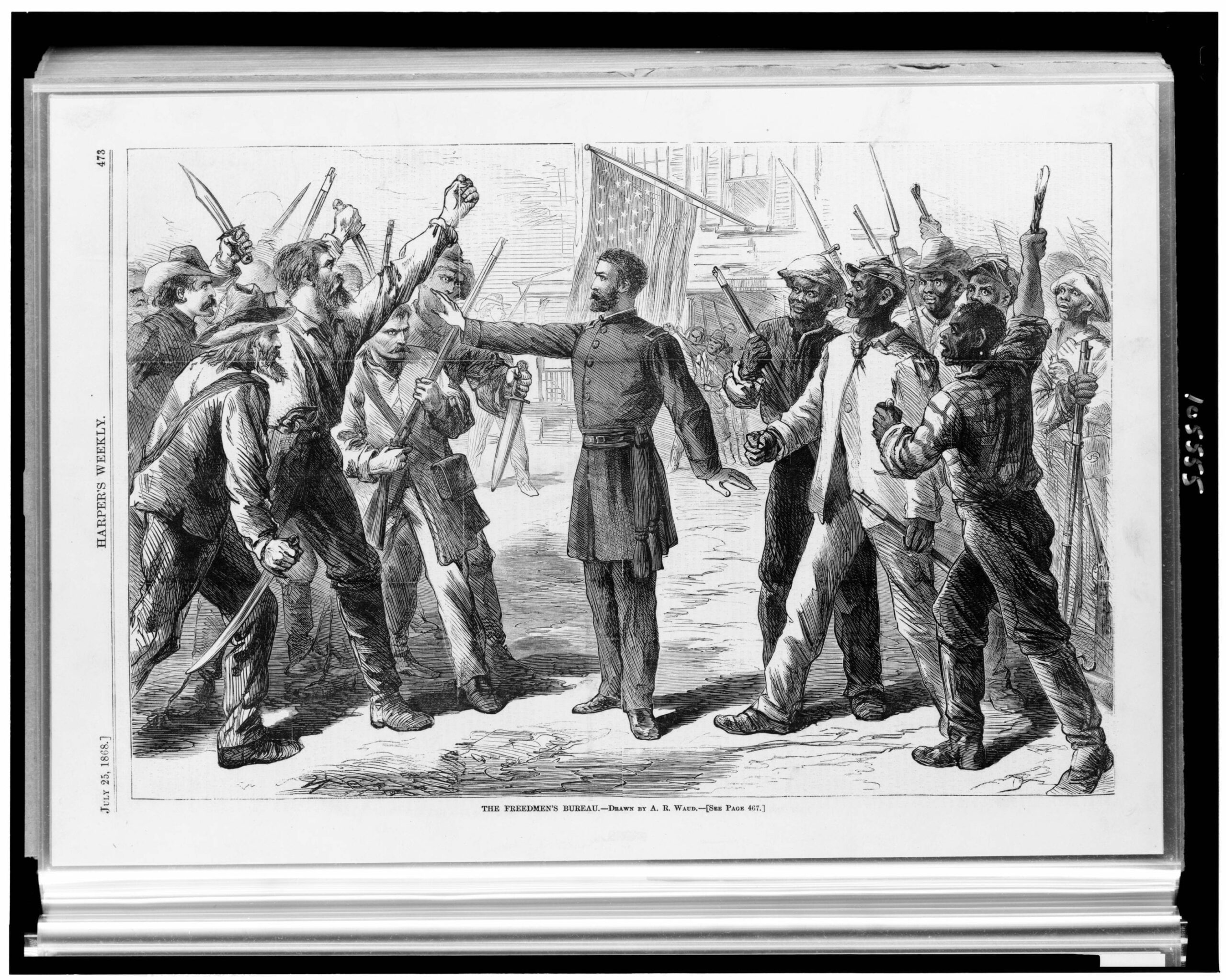

- Those whose principal object is to have the States without delay restored to their position and influence in the Union and the people of the States to the absolute control of their home concerns. They are ready, in order to attain that object, to make any ostensible concession that will not prevent them from arranging things to suit their taste as soon as that object is attained. This class comprises a considerable number, probably a large majority, of the professional politicians who are extremely active in the reconstruction movement. They are loud in their praise of the President’s reconstruction policy, and clamorous for the withdrawal of the Federal troops and the abolition of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

- The incorrigibles, who still indulge in the swagger which was so customary before and during the war, and still hope for a time when the Southern Confederacy will achieve its independence. This class consists mostly of young men, and comprises the loiterers of the towns and idlers of the country. They persecute Union men and Negroes whenever they can do so with impunity, insist clamorously upon their “rights,” and are extremely impatient of the presence of the Federal soldiers. A good many of them have taken the oaths of allegiance and amnesty, and associated themselves with the second class in their political operations. This element is by no means unimportant; it is strong in numbers, deals in brave talk, addresses itself directly and incessantly to the passions and prejudices of the masses, and commands the admiration of the women.

- The multitude of people who have no definite ideas about the circumstances under which they live and about the course they have to follow; whose intellects are weak, but whose prejudices and impulses are strong, and who are apt to be carried along by those who know how to appeal to the latter.

Much depends upon the relative strength and influence of these classes. In the course of this report you will find statements of facts which may furnish a basis for an estimate. But whatever their differences may be, on one point they are agreed: further resistance to the power of the National Government is useless, and submission to its authority a matter of necessity. . . .

. . . .

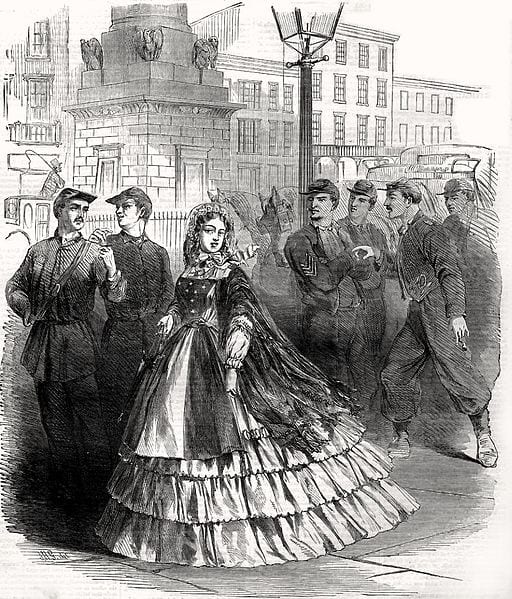

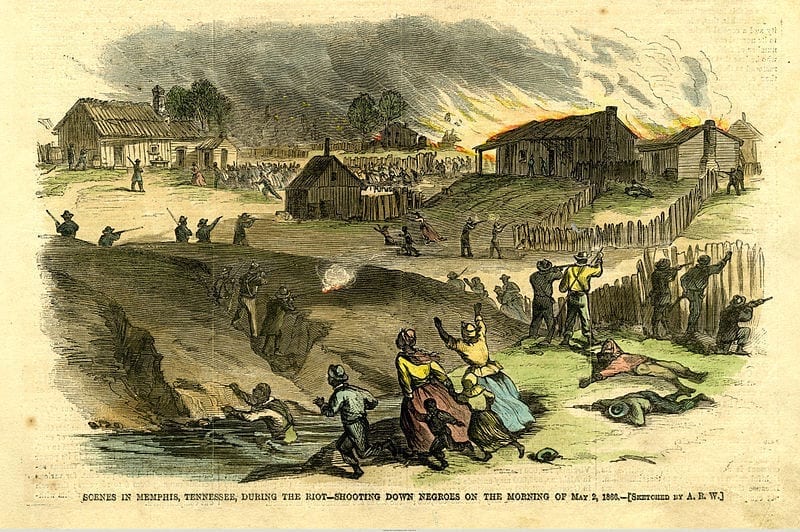

Feeling Toward the Soldiers and the People of the North

. . . [E]vidence of “returning loyalty” would be a favorable change of feeling with regard to the government’s friends and agents, and the people of the loyal States generally. I mentioned above that all organized attacks upon our military forces stationed in the South have ceased; but there are still localities where it is unsafe for a man wearing the federal uniform or known as an officer of the Government to be abroad outside of the immediate reach of our garrisons. The shooting of single soldiers and Government couriers was not unfrequently reported while I was in the South . . . .

. . . [N]o instance has come to my notice in which the people of a city or a rural district cordially fraternized with the army. . . . Upon the whole, the soldier of the Union is still looked upon as a stranger, an intruder – as the “Yankee,” “the enemy.” It would be superfluous to enumerate instances of insult offered to our soldiers, and even to officers high in command . . . .

Situation of Unionists

. . . It struck me soon after my arrival in the South that the known Unionists – I mean those who during the war had been to a certain extent identified with the National cause – were not in communion with the leading social and political circles; and the further my observation extended the clearer it became to me that their existence in the South was of a rather precarious nature. . . .

Even Governor Sharkey [of Mississippi], in the course of a conversation I had with him . . . admitted that, if our troops were then withdrawn, the lives of Northern men in Mississippi would not be safe. . . .

. . . .

What Has Been Accomplished

While the generosity and toleration shown by the government to the people lately in rebellion have not met with a corresponding generosity shown by those people to the Government’s friends, it has brought forth some results which, if properly developed, will become of value. It has facilitated the re-establishment of the forms of civil government, and led many of those who had been active in the rebellion to take part in the act of bringing back the states to their constitutional relations . . . .

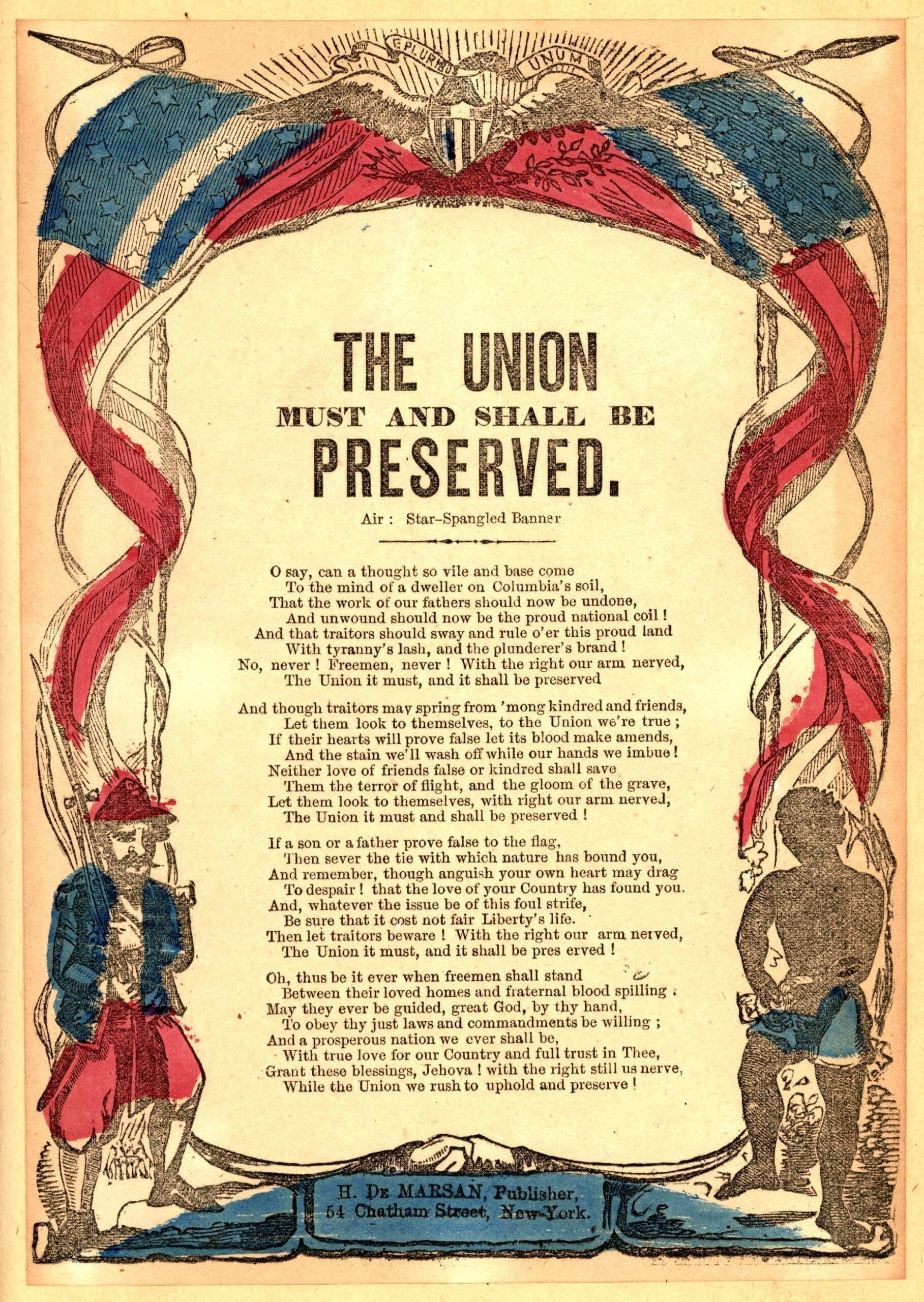

But as to the moral value of these results, we must not indulge in any delusions. There are two principal points to which I beg to call your attention. In the first place, the rapid return to power and influence of so many of those who but recently were engaged in a bitter war against the Union, has had one effect which was certainly not originally contemplated by the Government. Treason does, under existing circumstances, not appear odious in the South. The people are not impressed with any sense of its criminality. And, secondly, there is, as yet among the Southern people an utter absence of national feeling. I made it a business, while in the South, to watch the symptoms of “returning loyalty” as they appeared not only in private conversation, but in the public press and in the speeches delivered and the resolutions passed at Union meetings. Hardly ever was there an expression of hearty attachment to the great republic, or an appeal to the impulses of patriotism; but whenever submission to the National authority was declared and advocated, it was almost uniformly placed upon two principal grounds: That, under present circumstances, the Southern people could “do no better”; and then that submission was the only means by which they could rid themselves of the Federal soldiers and obtain once more control of their own affairs. . . .

The re-organization of civil government is relieving the military, to a great extent, of its police duties and judicial functions; but at the time I left the South it was still very far from showing a satisfactory efficiency in the maintenance of order and security. In many districts robbing and plundering were going on with perfect impunity; the roads were infested by bands of highwaymen; numerous assaults occurred and several stage lines were considered unsafe. . . .

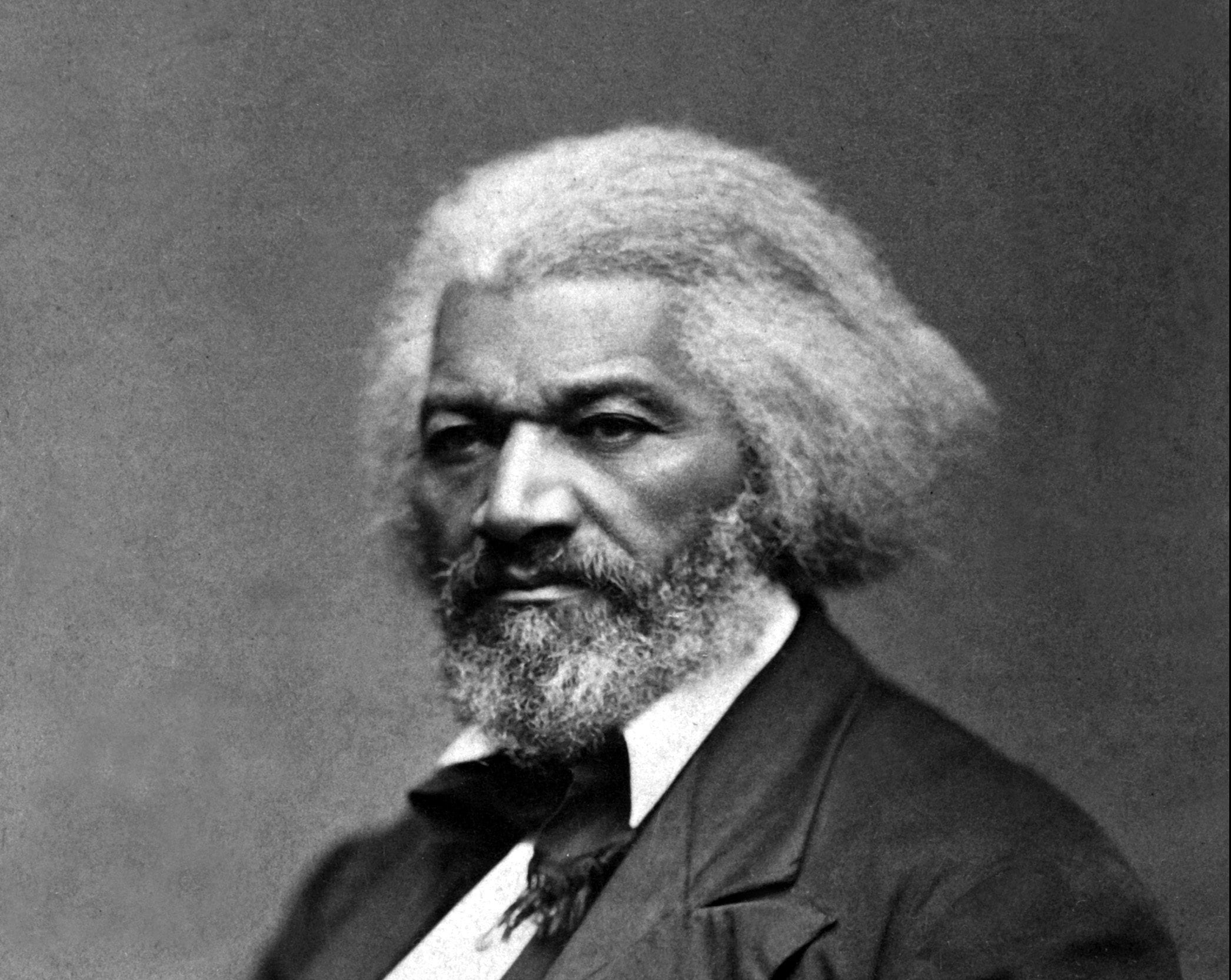

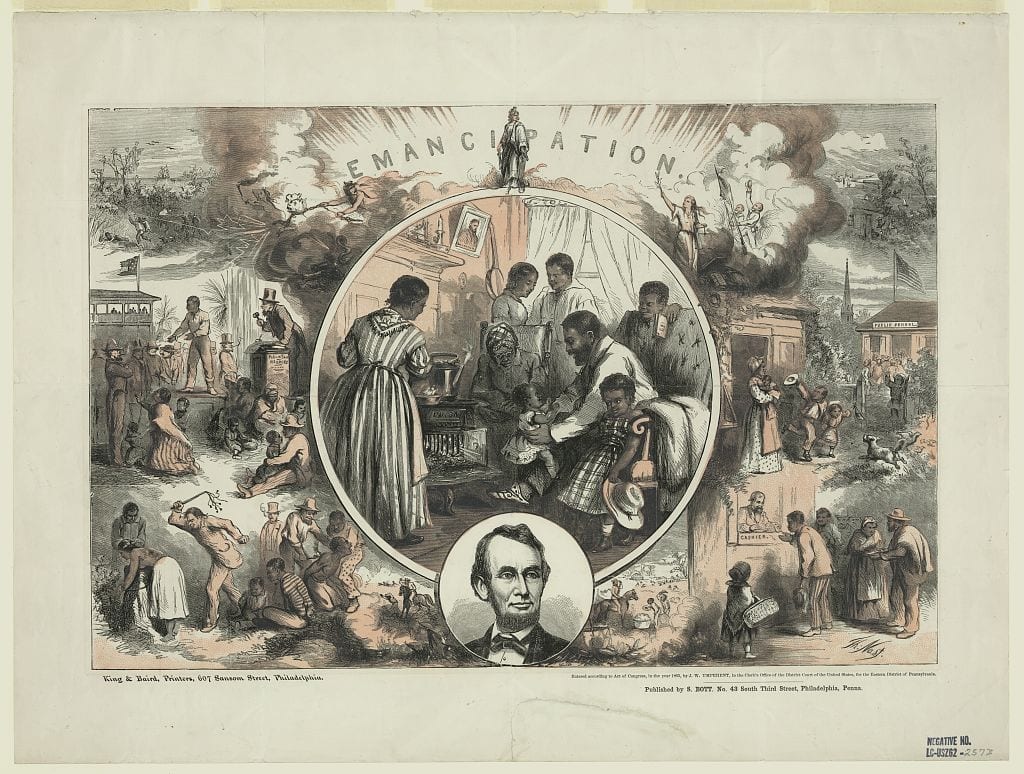

The Negro Question – First Aspects

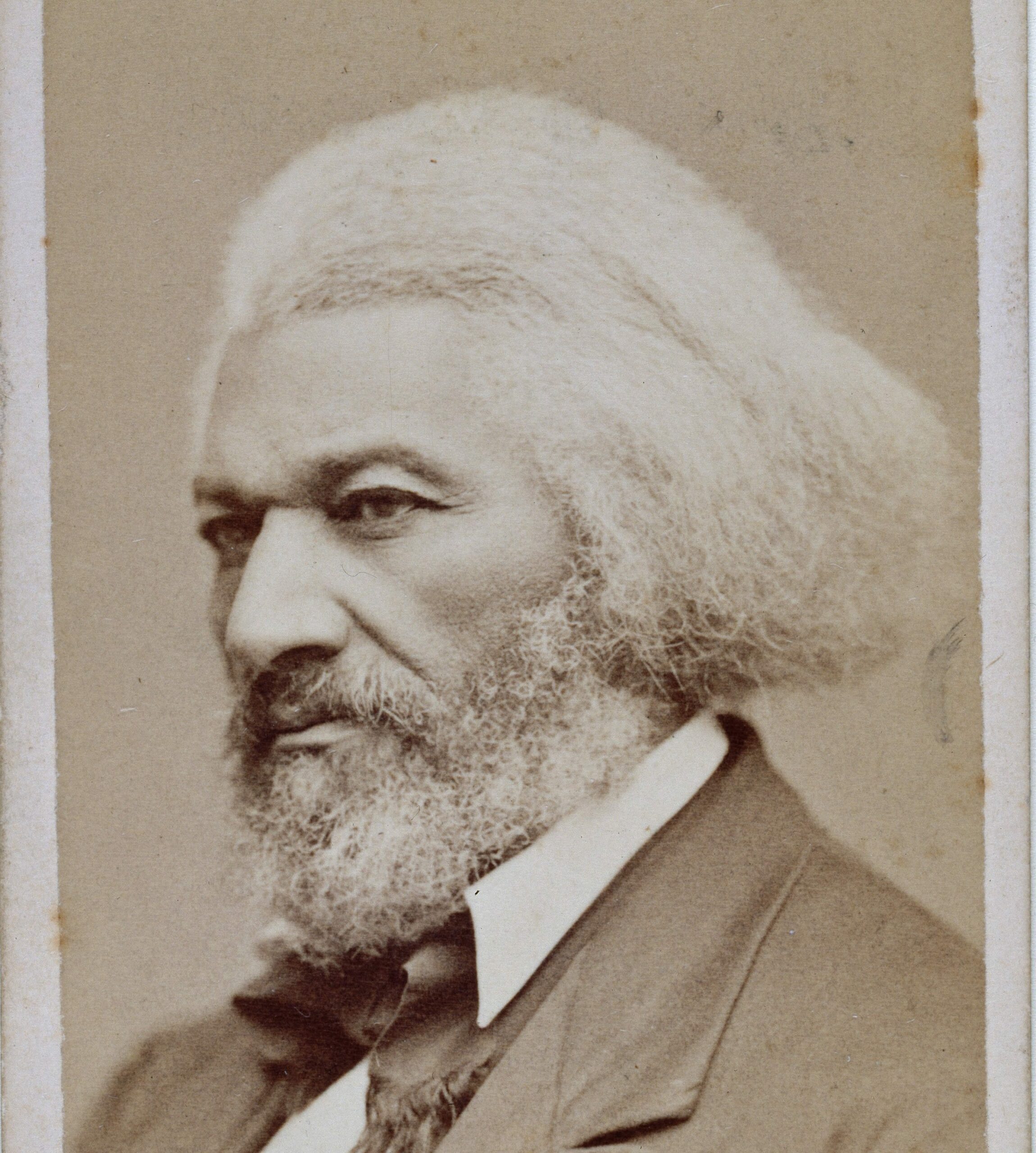

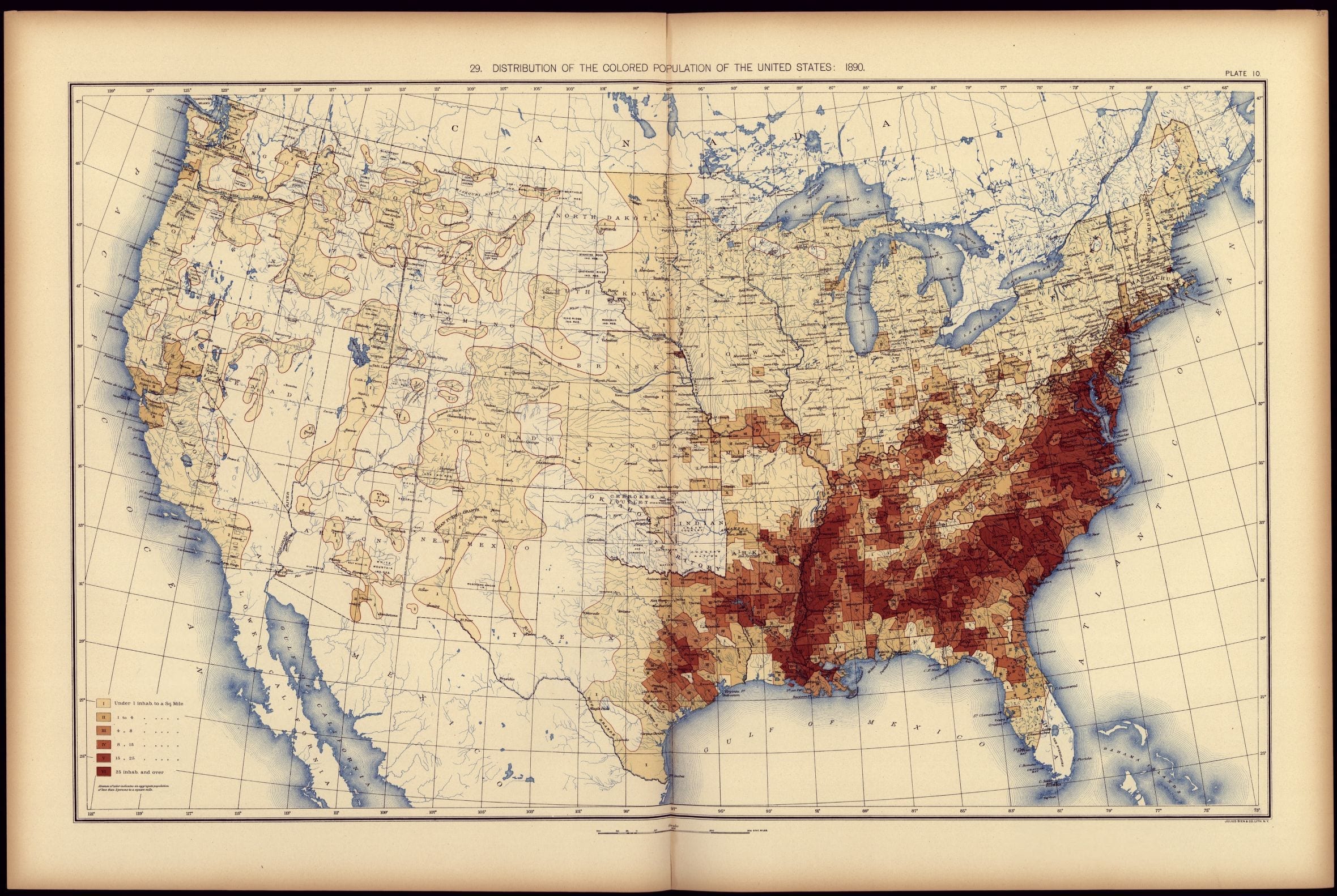

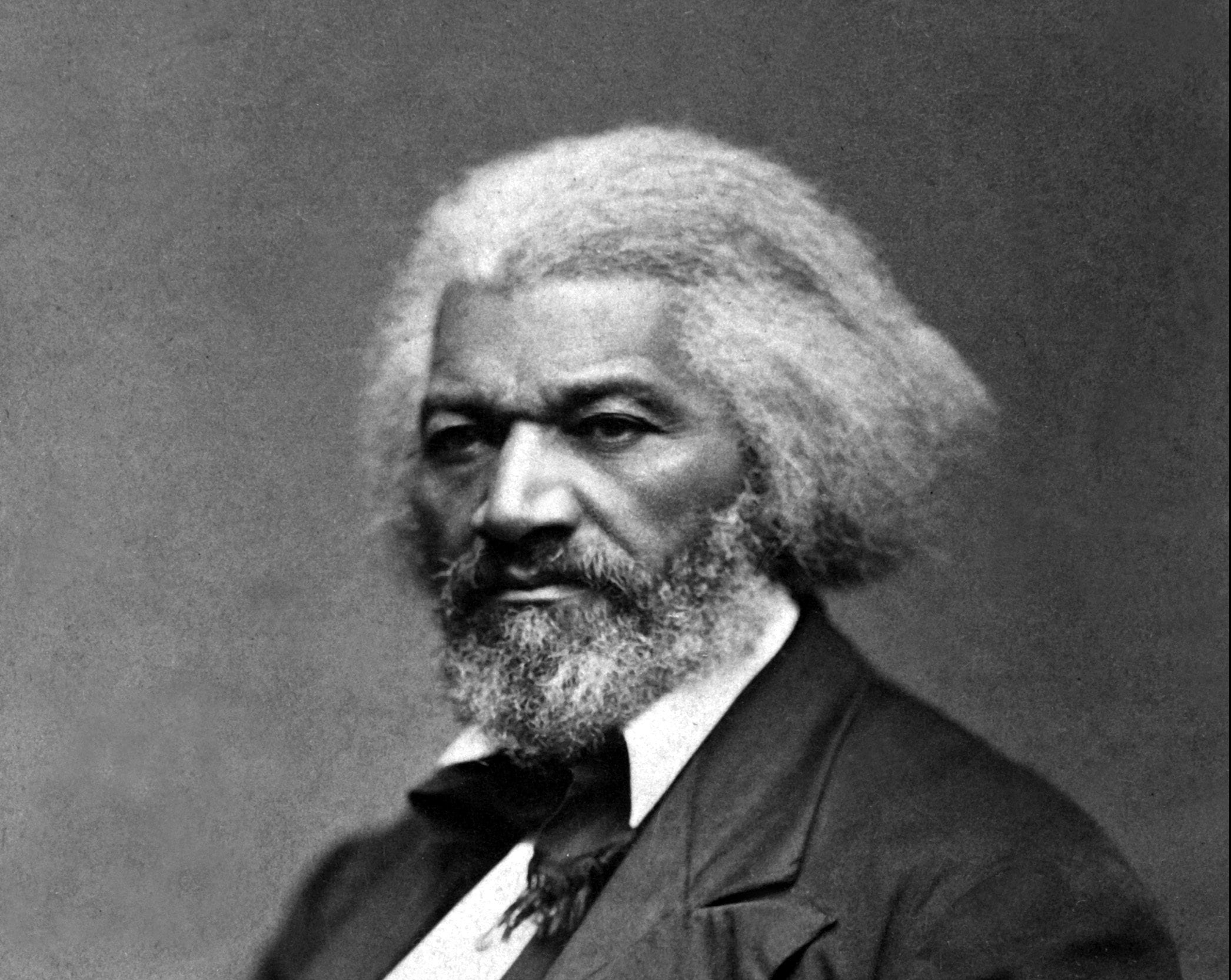

The principal cause of that want of national spirit which has existed in the South so long and at last gave birth to the rebellion, was, that the Southern people cherished, cultivated, idolized their peculiar interests and institutions in preference to those which they had in common with the rest of the American people. Hence the importance of the Negro question as an integral part of the question of union in general, and the question of reconstruction in particular.

. . .

Opinions of the Whites

. . . [A] large majority of the Southern men with whom I came into contact announced their opinions with so positive an assurance as to produce the impression that their minds where fully made up. In at least nineteen cases of twenty the reply I received to my inquiry about their views on the new system was uniformly this: “You cannot make the Negro work without physical compulsion.” I heard this hundreds of times, heard it wherever I went, heard it in nearly the same words from so many different persons, that at last I came to the conclusion that this is the prevailing sentiment among the Southern people. . . .

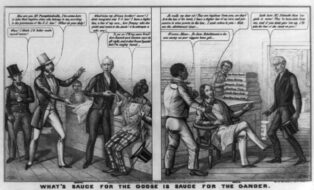

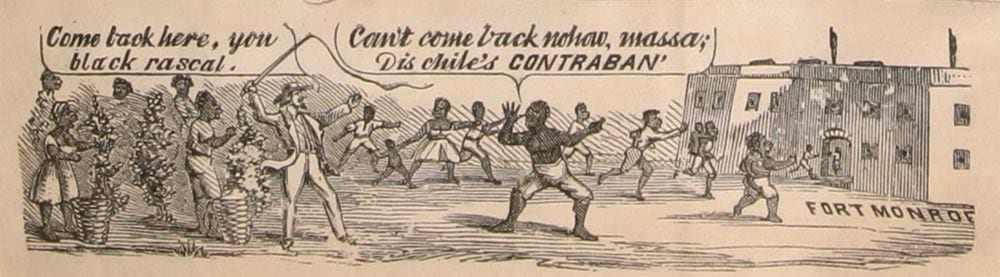

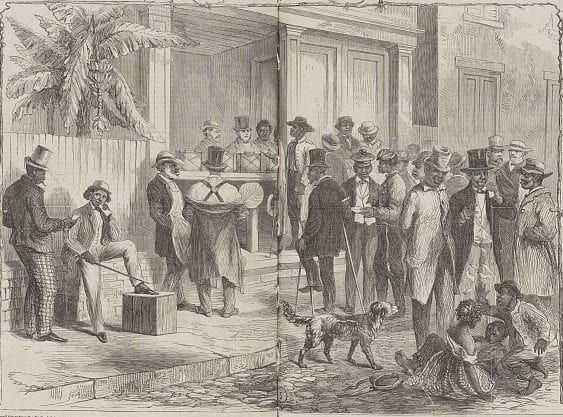

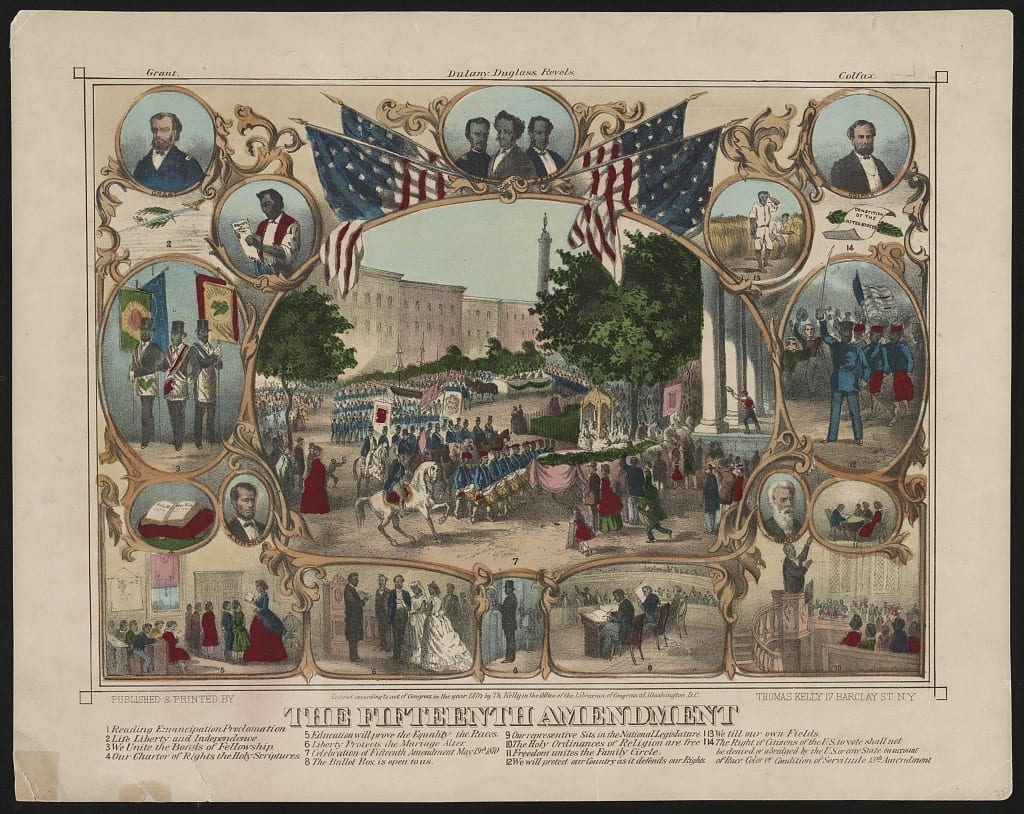

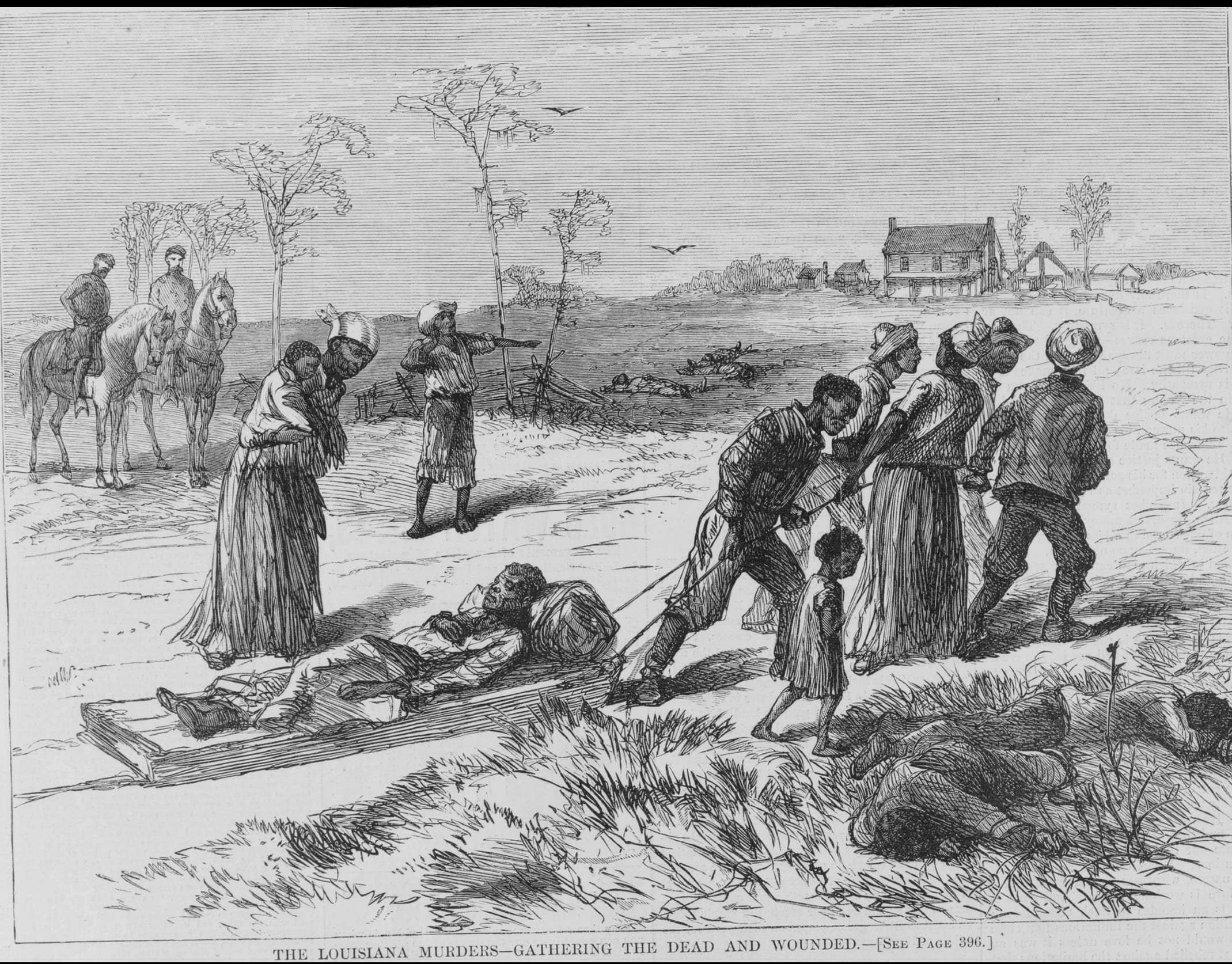

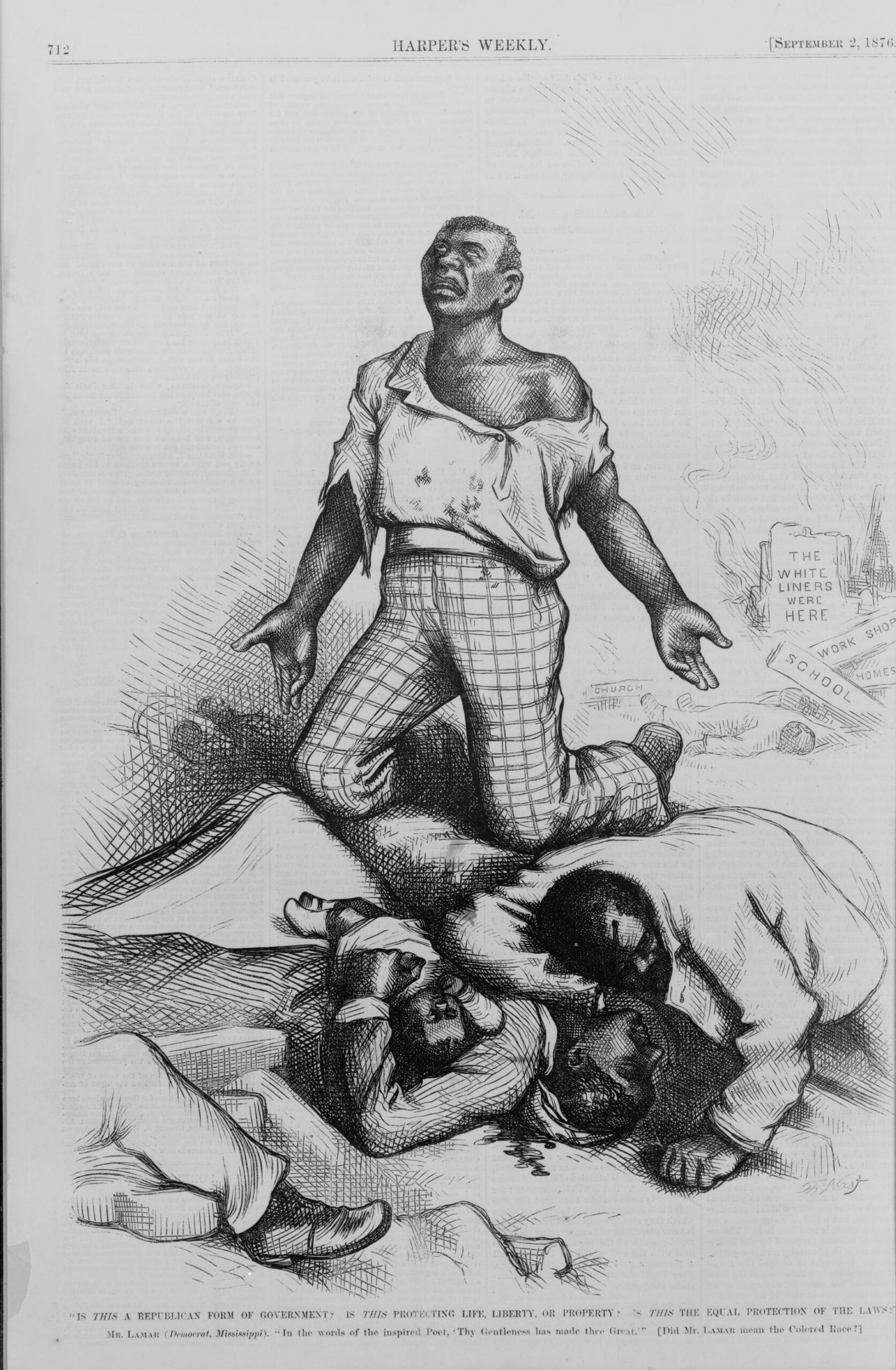

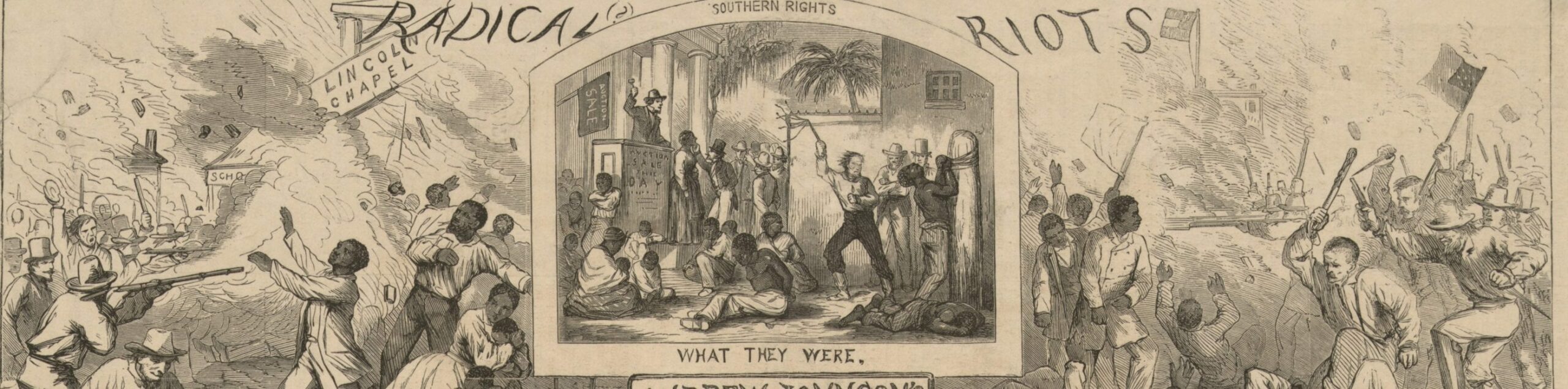

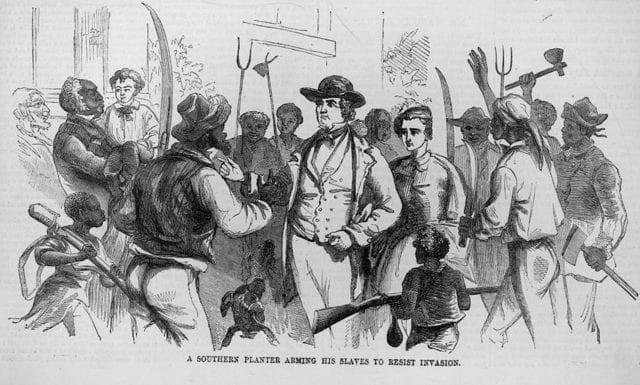

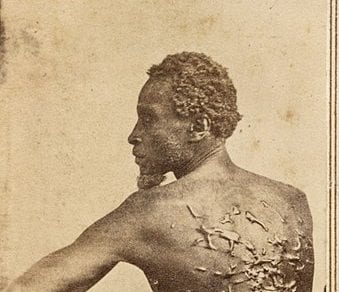

Effects of Such Opinions, and General Treatment of the Negro

A belief, conviction, or prejudice, or whatever you may call it, so widely spread and apparently so deeply rooted as this, that the Negro will not work without physical compulsion, is certainly calculated to have a very serious influence upon the conduct of the people entertaining it. It naturally produced a desire to preserve slavery in its original form as much and as long as possible – and you may, perhaps, remember the admission made by one of the provisional governors, over two months after the close of the war, that the people of his State still indulged in a lingering hope slavery might yet be preserved – or to introduce into the new system that element of physical compulsion which would make the Negro work. . . . In many instances Negroes who walked away from the plantations, or were found upon the roads, were shot or otherwise severely punished, which was calculated to produce the impression among those remaining with their masters that an attempt to escape from slavery would result in certain destruction. . . .

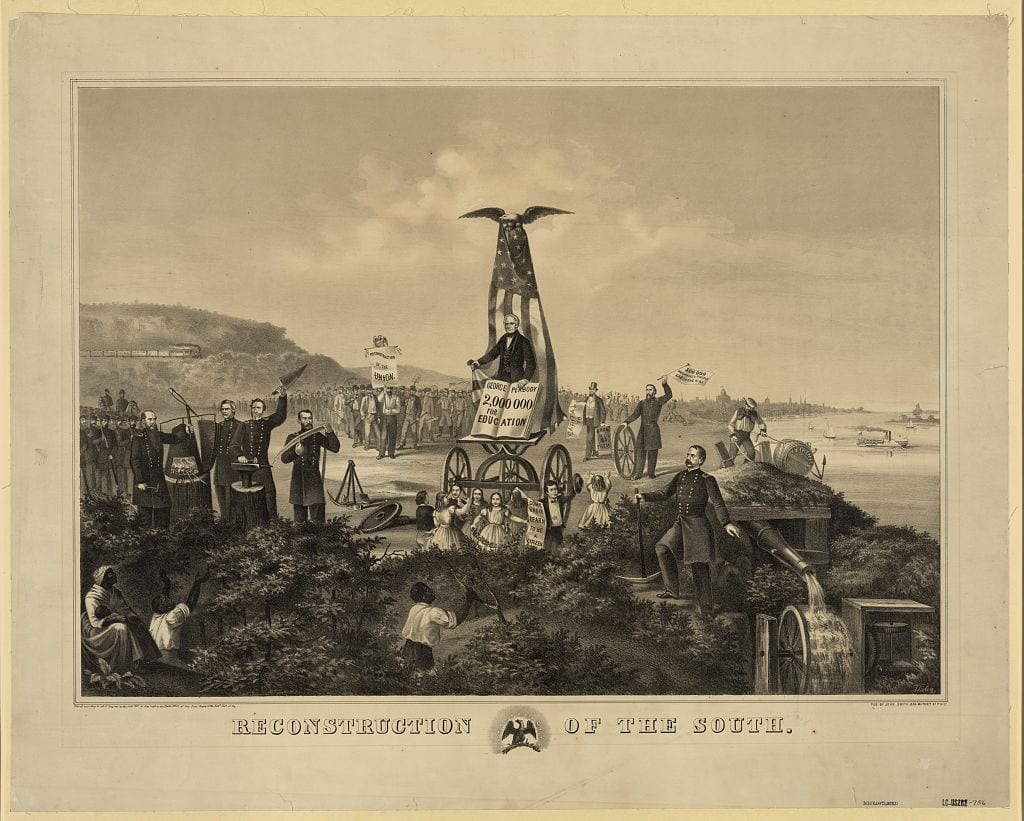

Education of the Freedmen

. . . As popular education is the true ground upon which the efficiency and the successes of free-labor society grow, no man who rejects the former can be accounted a consistent friend of the latter. It is also evident that the education of the Negro, to become general and effective after the full restoration of local government in the South, must be protected and promoted as an integral part of the educational systems of the States.

. . . [T]he popular prejudice is almost as bitterly set against the Negro’s having the advantage of education as it was when the negro was a slave. There may be an improvement in that respect, but it would prove only how universal the prejudice was in former days. Hundreds of times I heard the old assertion repeated, that “learning will spoil the nigger for work,” and that “Negro education will be the ruin of the South.” Another most singular notion still holds a potent sway over the minds of the masses – it is, that the elevation of the blacks will be the degradation of the whites. . . .

The consequence of the prejudice prevailing in the Southern States is that colored schools can be established and carried on with safety only under the protection of our military forces, and that where the latter are withdrawn the former have to go with them. . . .

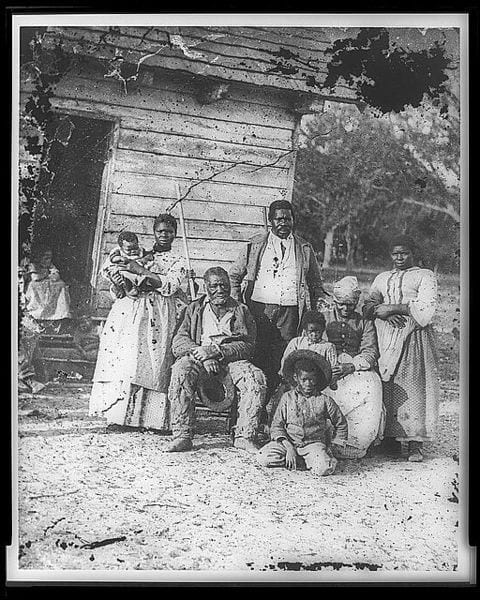

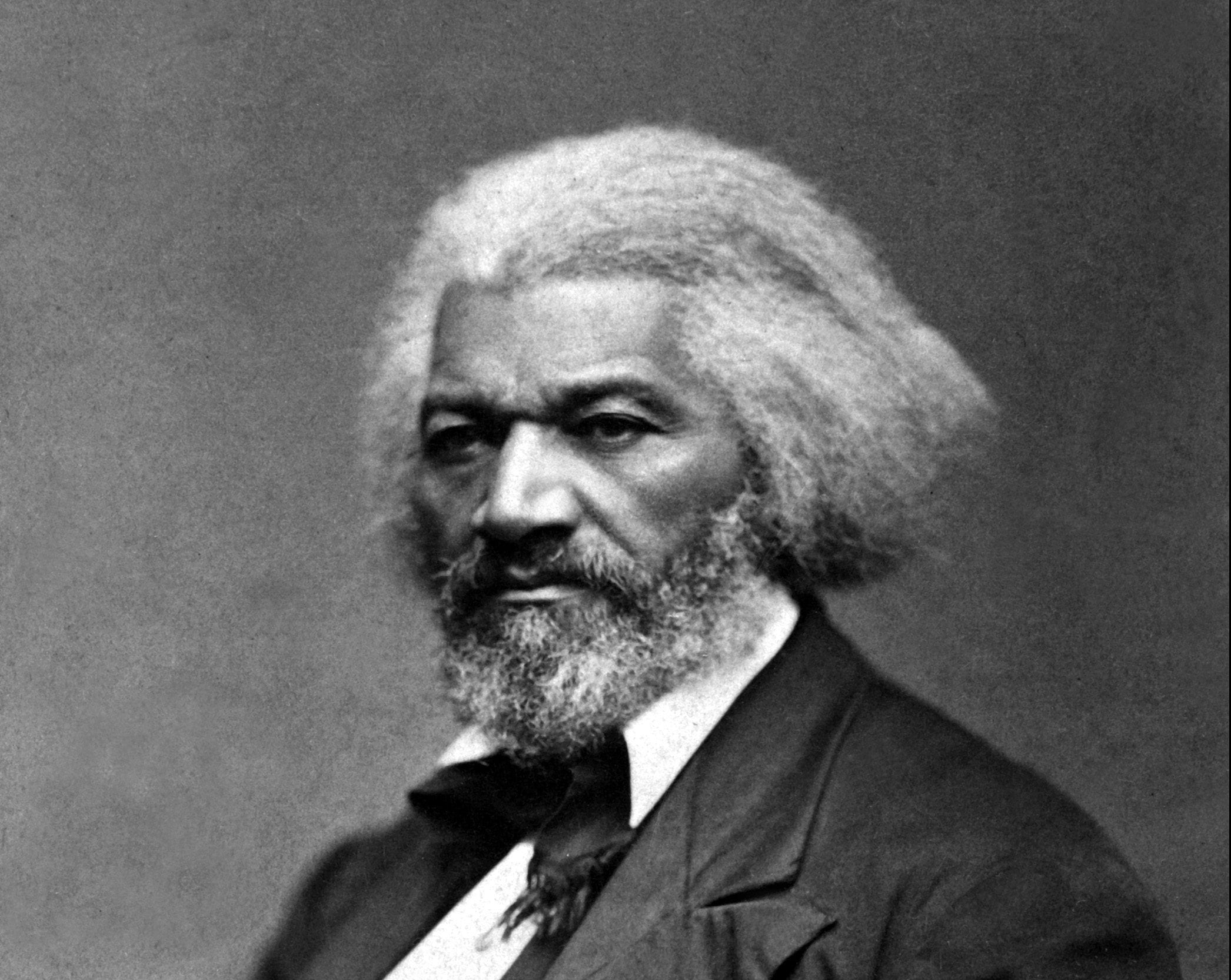

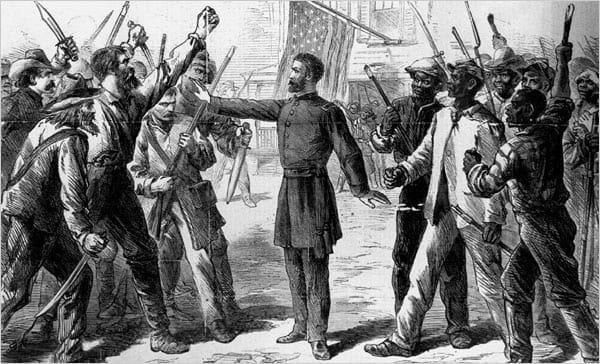

The Freedmen

The first Southern man with whom I came into contact after my arrival at Charleston designated the general conduct of the emancipated slaves as surprisingly good. Some went even so far as to call it admirable. . . . A great many colored people while in slavery had undoubtedly suffered much hardship and submitted to great wrongs, partly inseparably connected with the condition of servitude, and partly aggravated by the individual willfulness and cruelty of their masters and over seers. They were suddenly set free; and not only that: their masters, but a short time ago almost omnipotent on their domains, found themselves, after their defeat in the war, all at once face to face with their former, slaves as a conquered and powerless class. Never was the temptation to indulge in acts of vengeance for wrongs suffered more strongly presented than to the colored people of the South; but no instance of such individual revenge was then on record, nor have I since heard of any case of violence that could be traced to such motives. . . . This was the first impression I received after my arrival in the South, and I received it from the mouths of late slaveholders.

But at that point the unqualified praise stopped and the complaints began: the Negroes would not work; they left their plantations and went wandering from place to place, stealing by the way; they preferred a life of idleness and vagrancy to that of honest and industrious labor; they either did not show any willingness to enter into contracts, or, if they did, showed a stronger disposition to break them than to keep them; they were becoming insubordinate and insolent to their former owners; they indulged in extravagant ideas about their rights and relied upon the Government to support them without work; in one word, they had no conception of the rights freedom gave, and of the obligations freedom imposed upon them. . . .

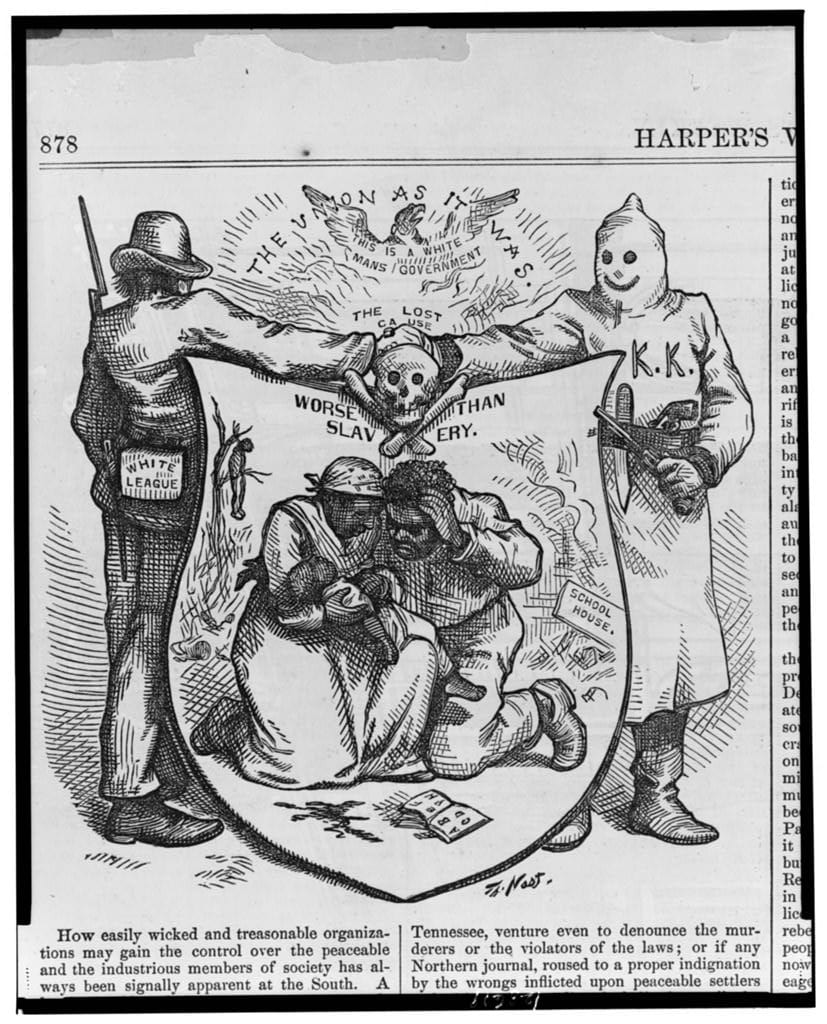

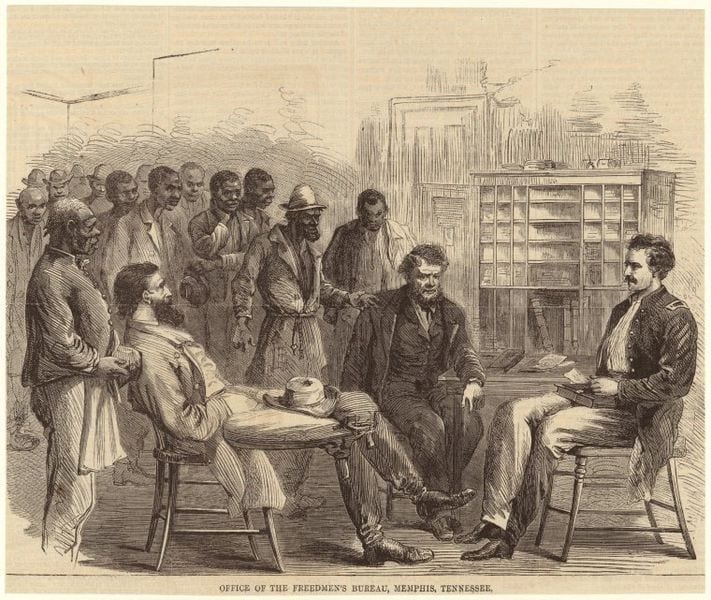

Prospective – the Reactionary Tendency

I stated above that, in my opinion, the solution of the social problem in the South did not depend upon the capacity and conduct of the Negro alone, but in the same measure upon the ideas and feelings entertained and acted upon by the whites. What their ideas and feelings were while under my observation, and how they affected the contact of the two races, I have already set forth. The question arises, what policy will be adopted by the “ruling class” when all restraint imposed upon them by the military power of the National Government is withdrawn, and they are left free to regulate matters according to their own tastes? It would be presumptuous to speak of the future with absolute certainty; but it may safely be assumed that the same causes will always tend to produce the same effect. As long as a majority of the Southern people believe that “the Negro will not work without physical compulsion,” and that “the blacks at large belong to the whites at large,” that belief will tend to produce a system of coercion, the enforcement of which will be aided by the hostile feeling against the Negro now prevailing among the whites, and by the general spirit of violence which in the South was fostered by the influence slavery exercised upon the popular character. It is, indeed, not probable that a general attempt will be made to restore slavery in its old form, on account of the barriers which such an attempt would find in its way; but there are systems intermediate between slavery as it formerly existed in the South, and free labor as it exists in the North, but more nearly related to the former than to the latter, the introduction of which will be attempted. I have already noticed some movements in that direction, which were made under the very eyes of our military authorities, and of which the Opelousas and St. Landry ordinances3 were the most significant. . . .

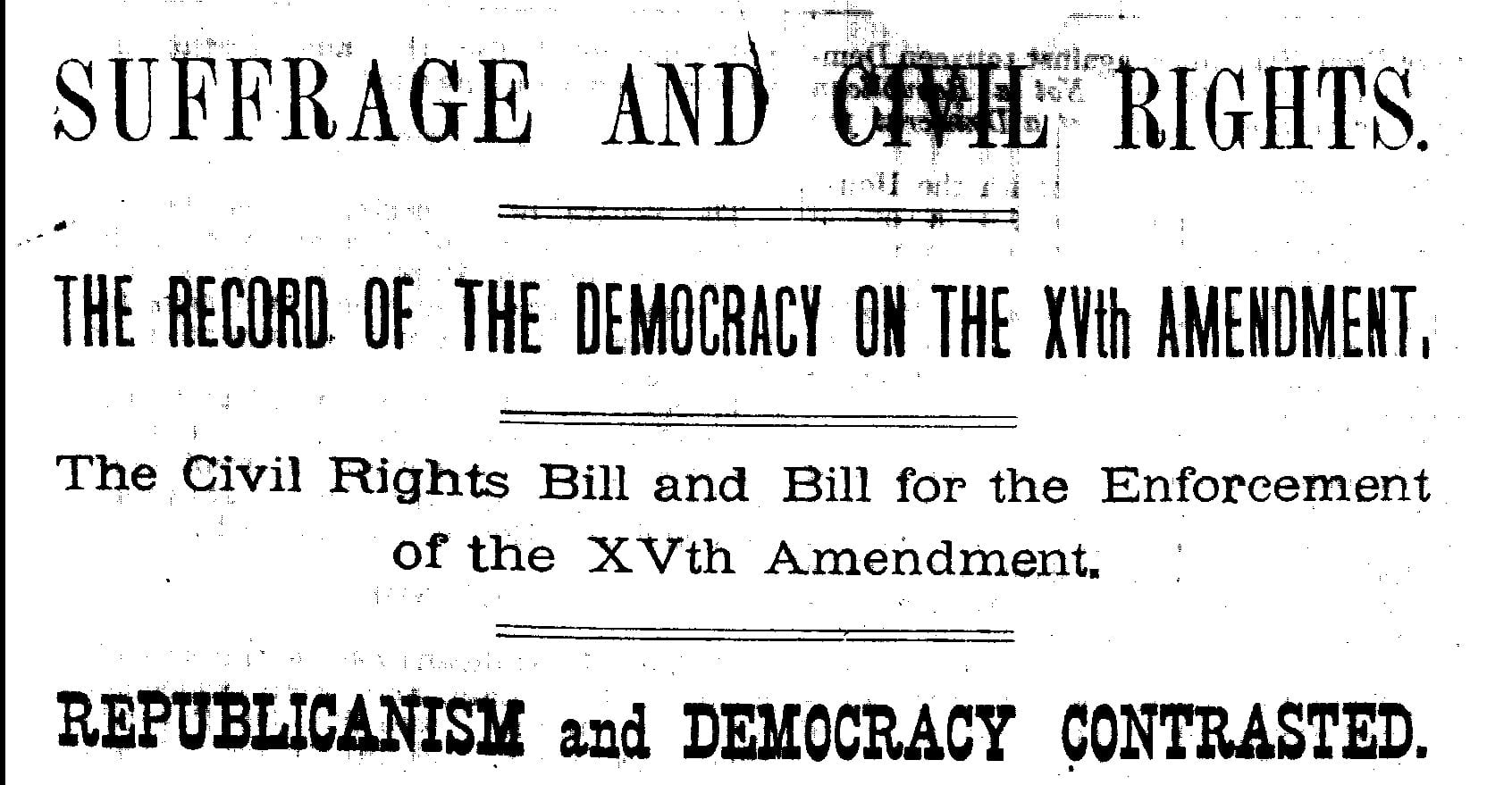

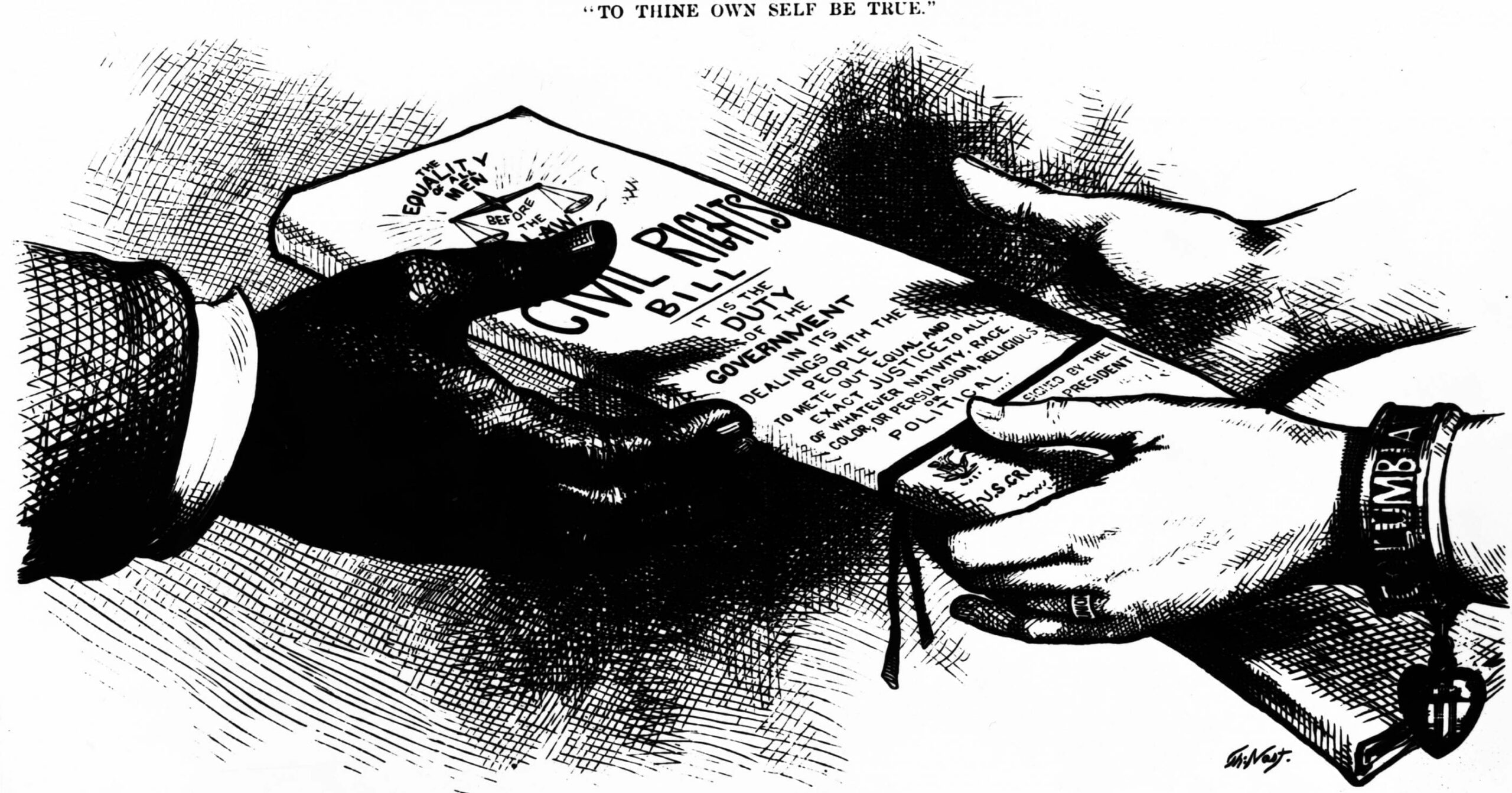

It is worthy of note that the convention of Mississippi – and the conventions of other States have followed its example – imposed upon subsequent legislatures the obligation not only to pass laws for the protection of the freedmen in person and property, but also to guard against the dangers arising from sudden emancipation. This language is not without significance; not the blessings of a full development of free labor, but only the dangers of emancipation are spoken of. It will be observed that this clause is so vaguely worded as to authorize the legislatures to place any restriction they may see fit upon the emancipated Negro, in perfect consistency with the amended State Constitutions; for it rests with them to define what the dangers of sudden emancipation consist in, and what measures may be required to guard against them. It is true, the clause does not authorize the legislatures to reestablish slavery in the old form; but they may pass whatever laws they see fit, stopping short only one step of what may strictly be defined as “slavery.” Peonage of the Mexican pattern, or serfdom of some European pattern, may under that clause be considered admissible; . . . it appears not only possible, but eminently probable, that the laws which will be passed to guard against the dangers arising from emancipation will be directed against the spirit of emancipation itself. . . .

. . .

The True Problem – Difficulties and Remedies

. . . [I]t is not only the Political machinery of the States and their constitutional relations to the General Government, but the whole organism of Southern society that must be reconstructed, or rather constructed anew, so as to bring it in harmony with the rest of American society. . . .

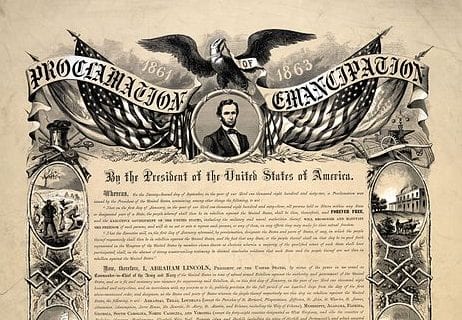

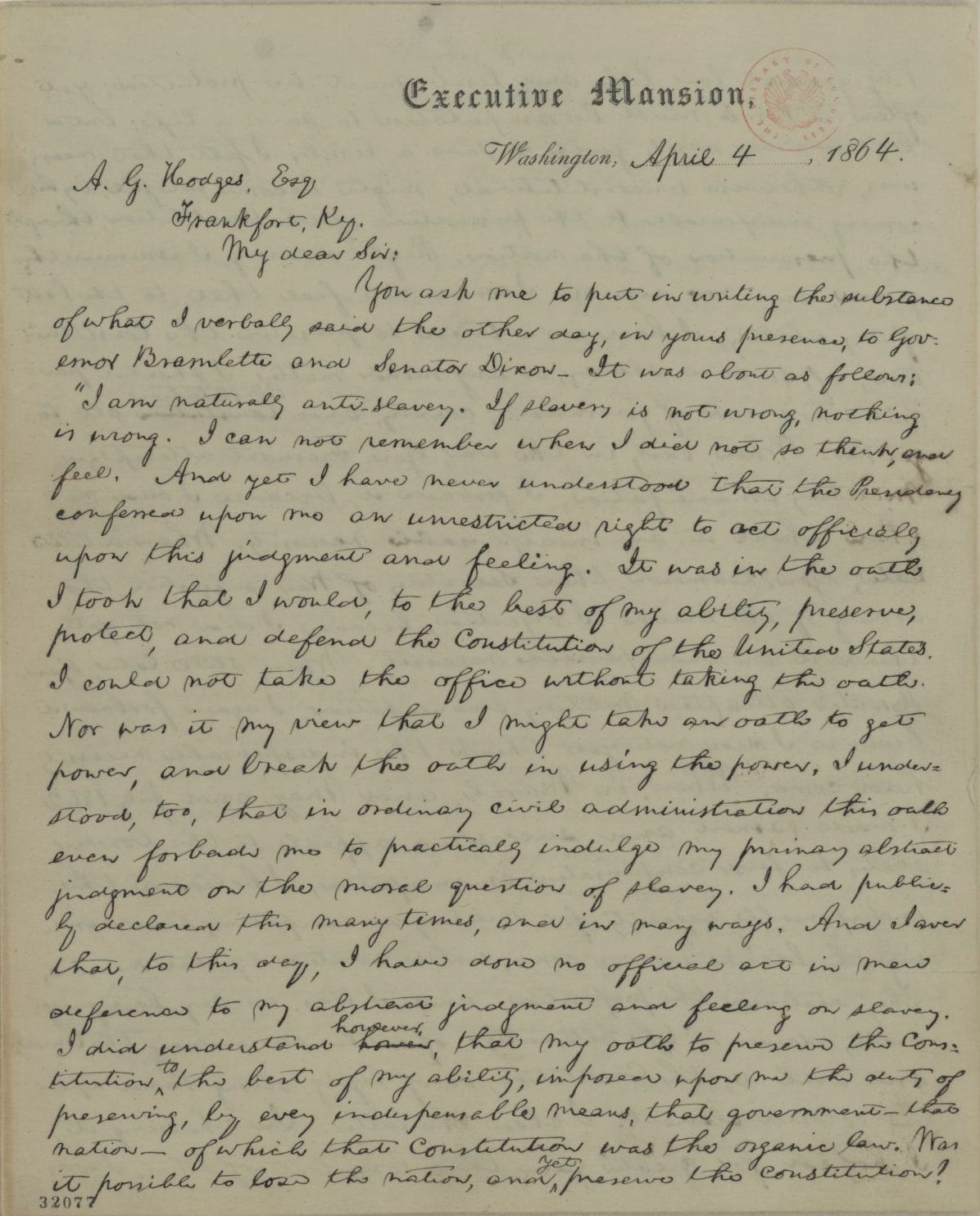

The true nature of the difficulties of the situation is this: The General Government of the republic has, by proclaiming the emancipation of the slaves, commenced a great social revolution in the South, but has, as yet, not completed it. . . .

. . . It is, indeed, difficult to imagine circumstances more unfavorable for the development of a calm and unprejudiced public opinion than those under which the Southern people are at present laboring. The war has not only defeated their political aspirations, but it has broken up their whole social organization. When the rebellion was put down, they found themselves not only conquered in a political and military sense, but economically ruined. . . . The planters . . . are partly laboring under the severest embarrassments, partly reduced to absolute poverty. Many who are stripped of all available means, and have nothing but their land, cross their arms in gloomy despondency . . . . Others, who still possess means, are at a loss how to use them, as their old way of doing things is, by the abolition of slavery, rendered impracticable, at least where the military arm of the government has enforced emancipation. . . . A large number of the plantations . . . [are] under heavy mortgages, and the owners know that, unless they retrieve their fortunes in a comparatively short space of time, their property will pass out of their hands. . . . Besides, the Southern soldiers, when returning from the war, did not, like the Northern soldiers, find a prosperous community which merely waited for their arrival to give them remunerative employment. [Many] found their homesteads destroyed, their farms devastated, their families in distress; and [others found] an impoverished and exhausted community which had but little to offer them. . . . [A] nervous anxiety to hastily repair broken fortunes, and to prevent still greater ruin and distress, embraces nearly all classes . . . .

. . . The practical question presents itself: Is the immediate restoration of the late rebel States to absolute self-control so necessary that it must be done even at the risk of endangering one of the great results of the war, and of bringing on in those States insurrection or anarchy, or would it not be better to postpone that restoration until such dangers are passed? If, as long as the change from slavery to free labor is known to the Southern people only by its destructive results, these people must be expected to throw obstacles in its way, would it not seem necessary that the movement of social “reconstruction” be kept in the right channel by the hand of the power which originated the change, until that change can have disclosed some of its beneficial effects? . . .

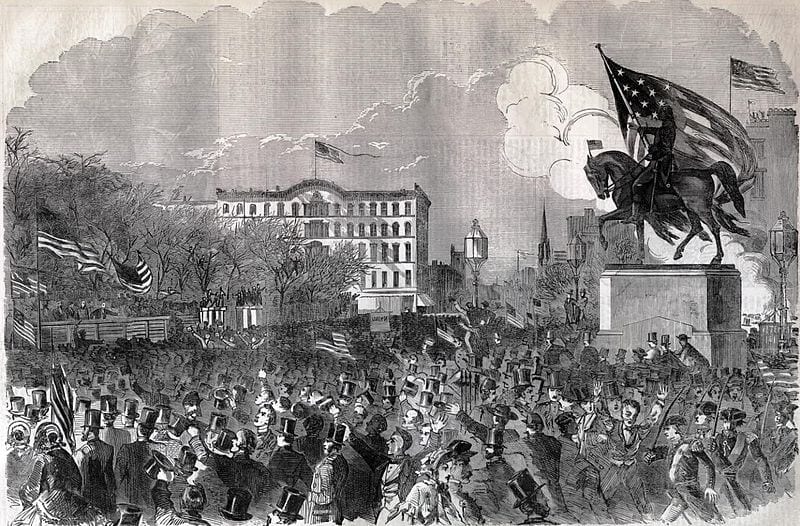

. . . One reason why the southern people are so slow in accommodating themselves to the new order of things is, that they confidently expect soon to be permitted to regulate matters according to their own notions. Every concession made to them by the government has been taken as an encouragement to preserve in this hope, and, unfortunately for them, this hope is nourished by influences from other parts of the country. Hence their anxiety to have their State governments restored at once, to have the troops withdrawn. . . .

- 1. Although Schurz, having broken with President Johnson’s policies before completing his report, would deliver it not to the president but to the Senate, he nevertheless wrote it as if it were addressed to the President.

- 2. See "Reorganizing Constitutional Government in Mississippi": The North Carolina Proclamation, President Johnson’s first on May 29, 1865, was structurally identical to the Mississippi Proclamation, which he submitted days later. For the North Carolina Proclamation, see https://goo.gl/gg1ugD.

- 3. Schurz is referring to the locales that passed black codes.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.