No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

After months of planning, in the late evening of October 16, 1859, radical abolitionist John Brown and his followers attacked the federal armory, arsenal, and rifle factory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. From there, they had planned to arm and lead the local slaves in rebellion, but for a number of reasons, were unable to spread the alarm. Instead, the insurrectionists swiftly found themselves blockaded within the armory under attack from local and federal forces. Fighting continued intermittently for the next few days with casualties on both sides. Finally, on October 18, Brown and the remaining members of his band were overwhelmed and arrested.

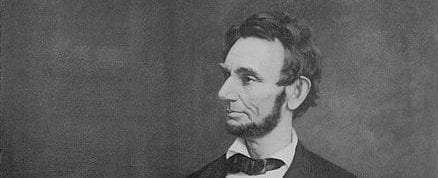

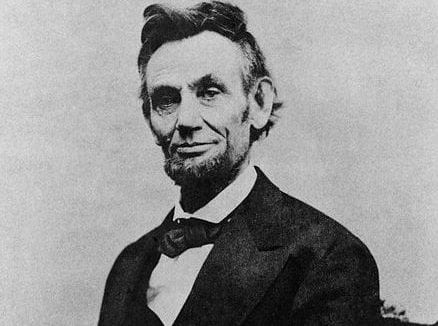

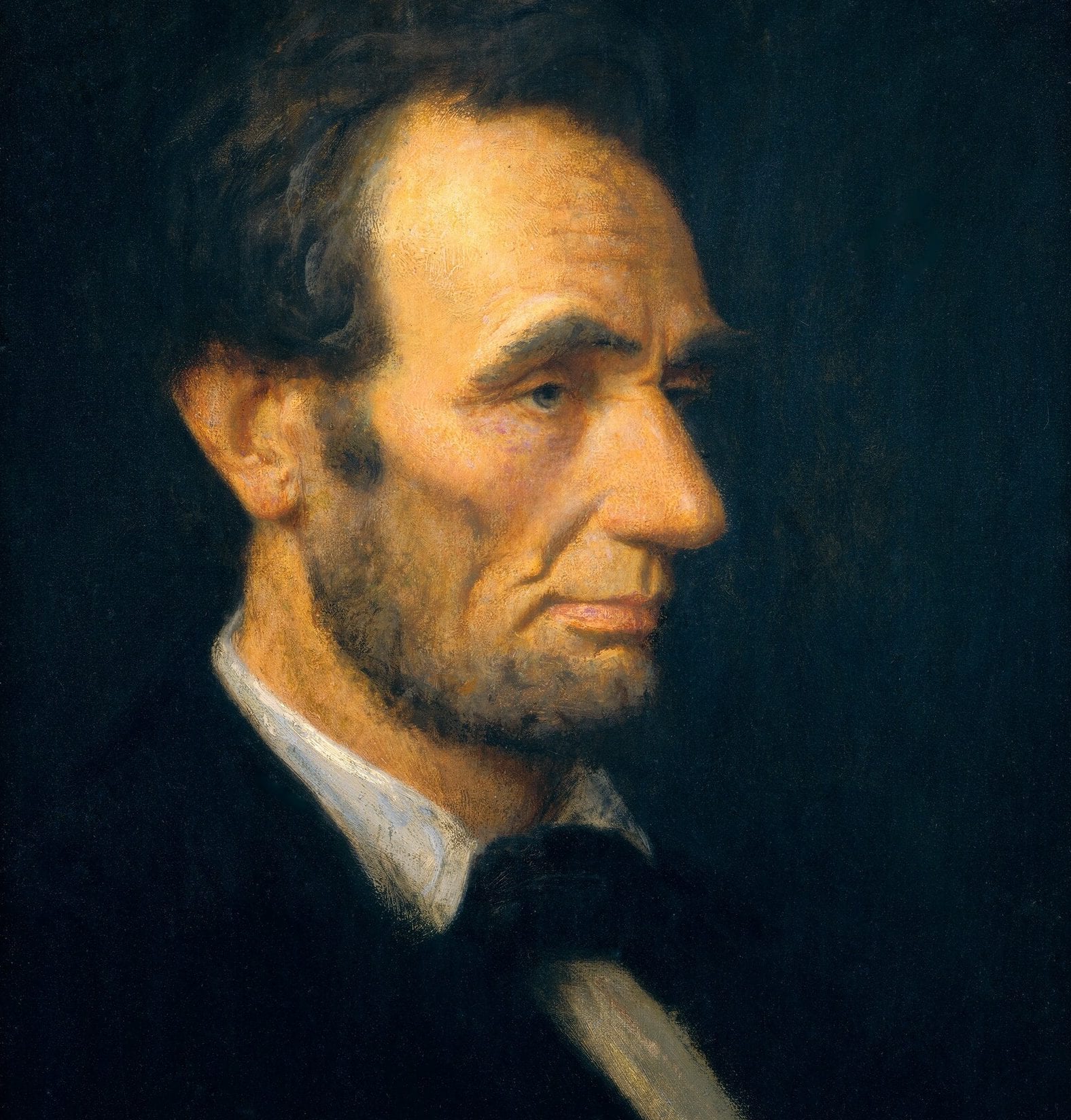

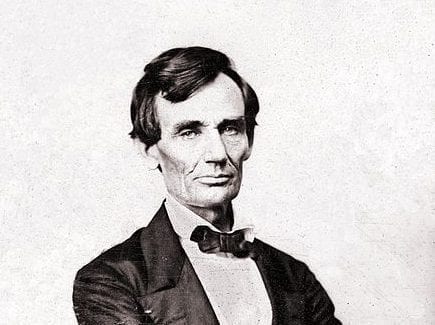

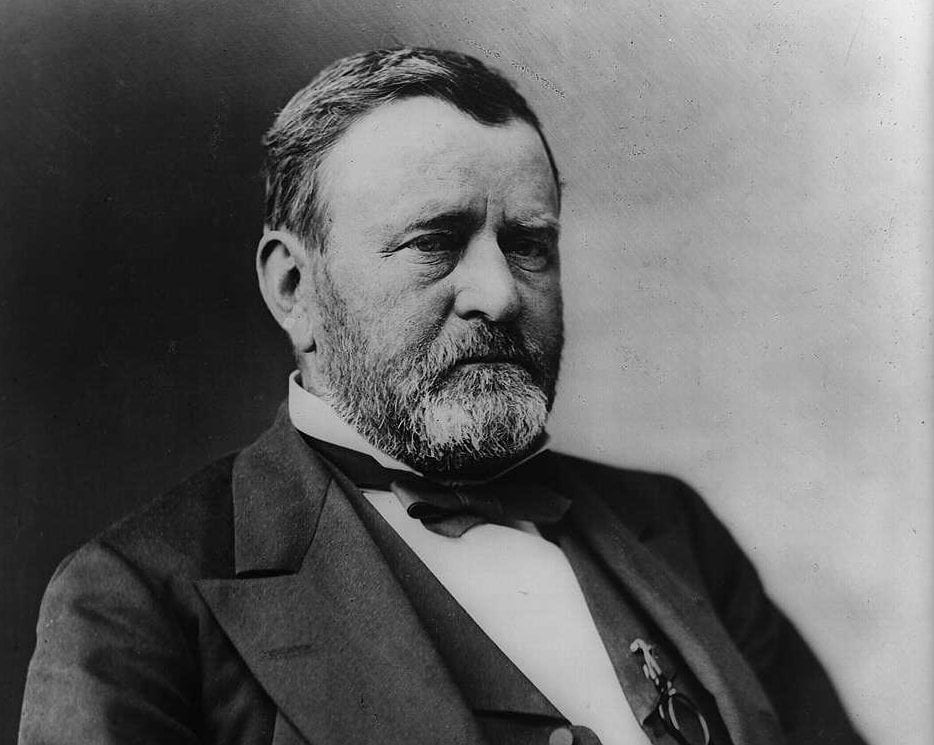

Reports of the incident immediately aroused a heated public discourse. Even many Northerners sympathetic to Brown’s abolitionist tendencies found his methods deplorable and labeled him a madman; although others insisted on not only the sanity but righteousness of his actions (Documents A, C, D). Southerners like Governor Henry Wise insisted that Brown be treated as a cold-blooded murderer (Document A) and observers on both sides made much of the fact that no actual slaves joined in the insurrection (Documents B and E). Brown’s eventual execution did not end the furor, as the Southern leaders insisted that the policies advocated by the new Republican Party would inevitably result in more such violence (Document E; see also Chapter 15). Despite the efforts of Abraham Lincoln and others to downplay the significance of the event, Brown’s name and story became a rallying cry for the anti-slavery cause and eventually, for the Union troops in the Civil War (Document F).

Documents in this chapter are available separately by following the hyperlinks below:

A. Lydia Maria Child, Governor Henry Wise of Virginia, and John Brown, Correspondence, October 1859

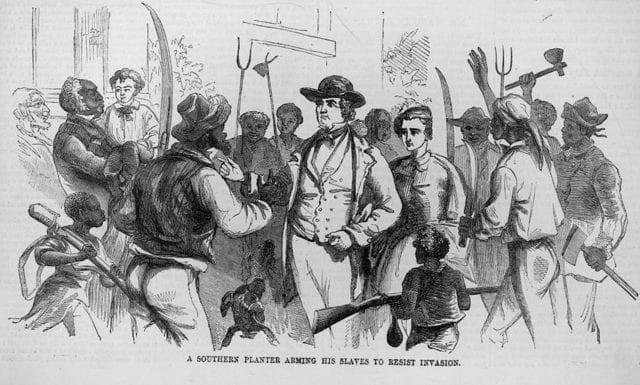

B. D. H. Strother, A Southern Planter Arming His Slaves to Resist Invasion, November 19, 1859

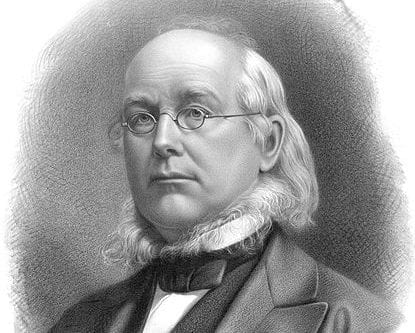

C. Horace Greeley, “The Whole Affair Seems the Work of a Madman,” October 19, 185

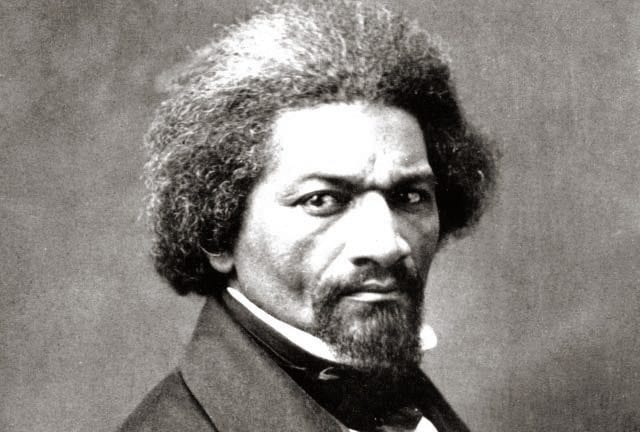

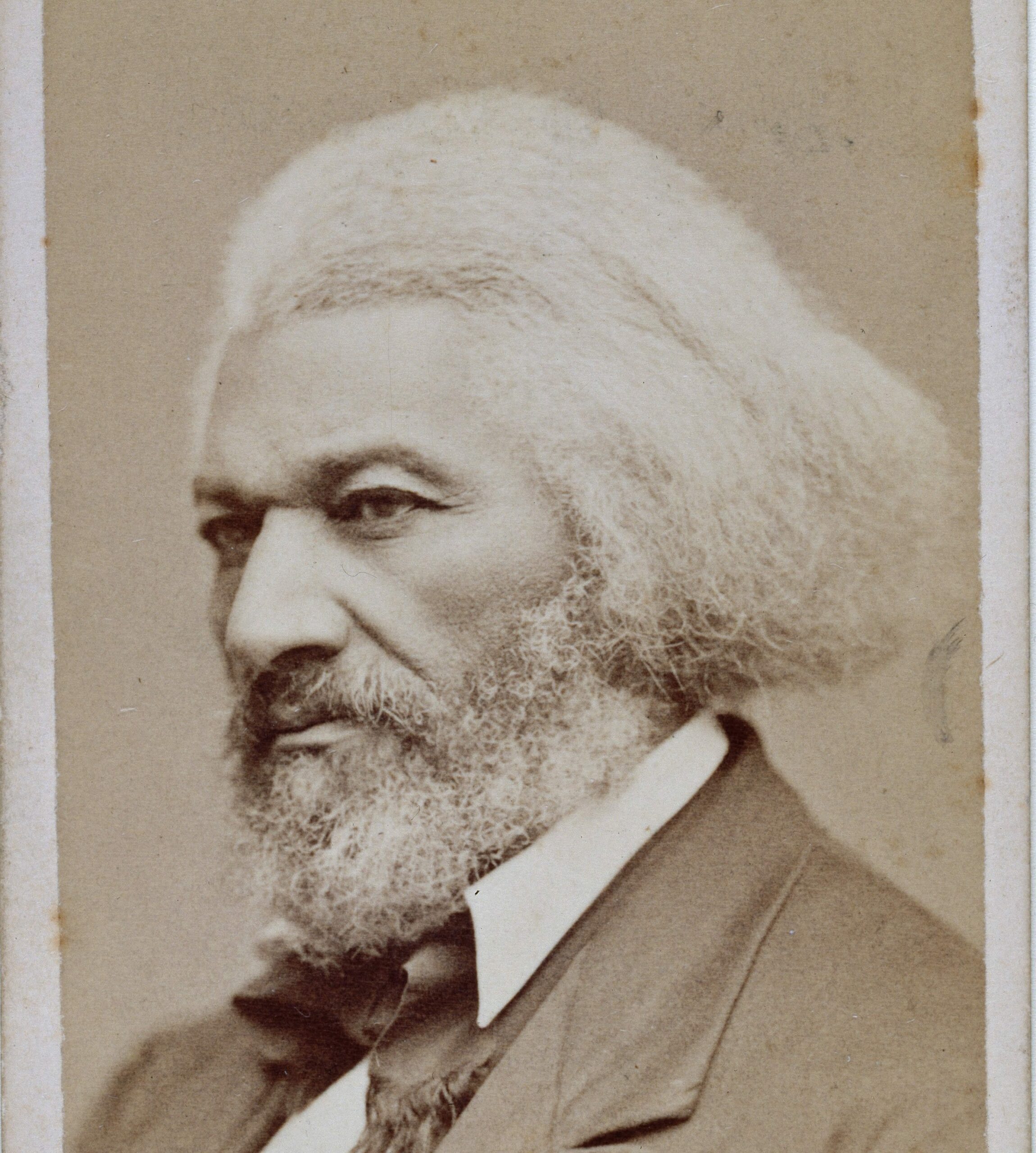

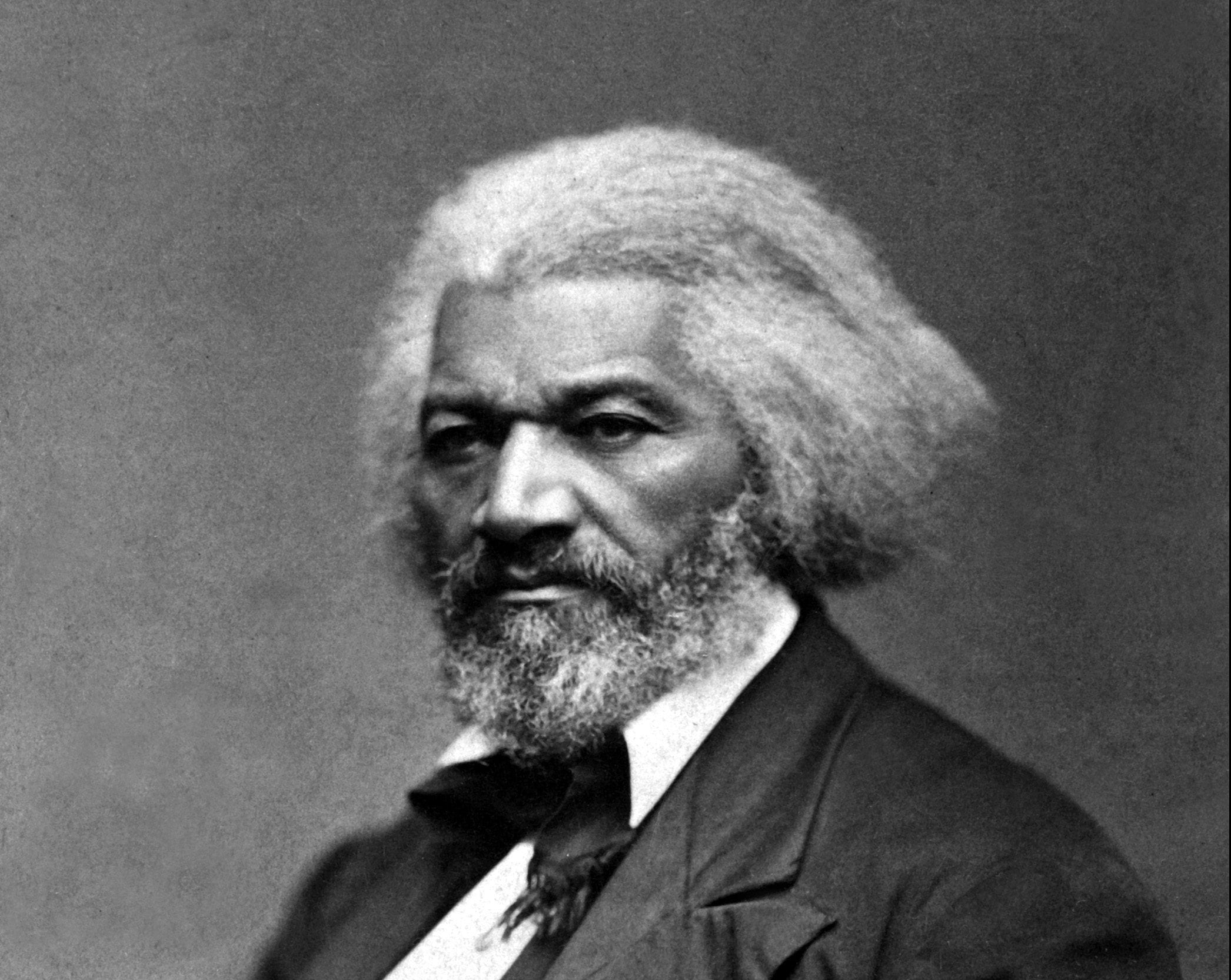

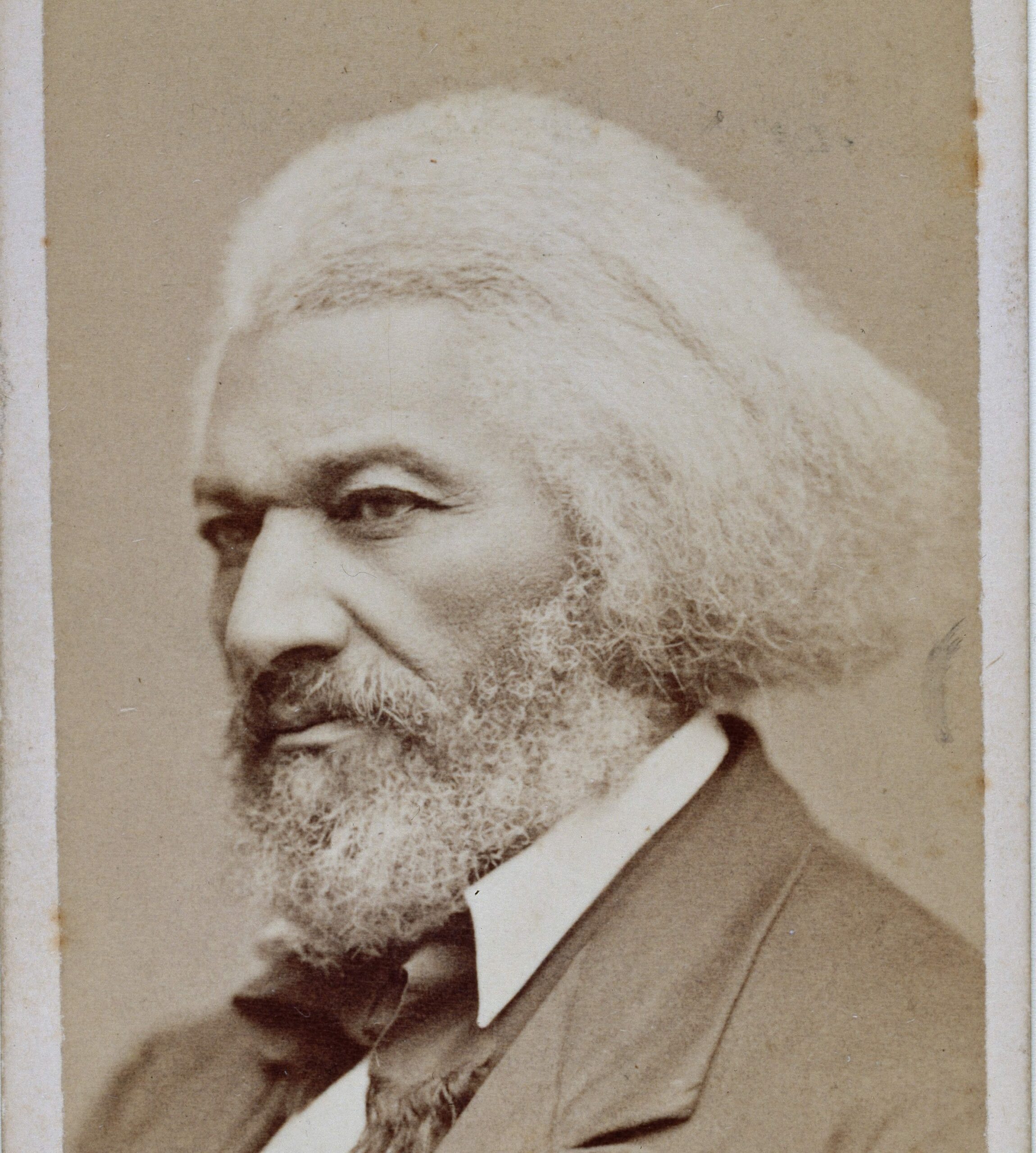

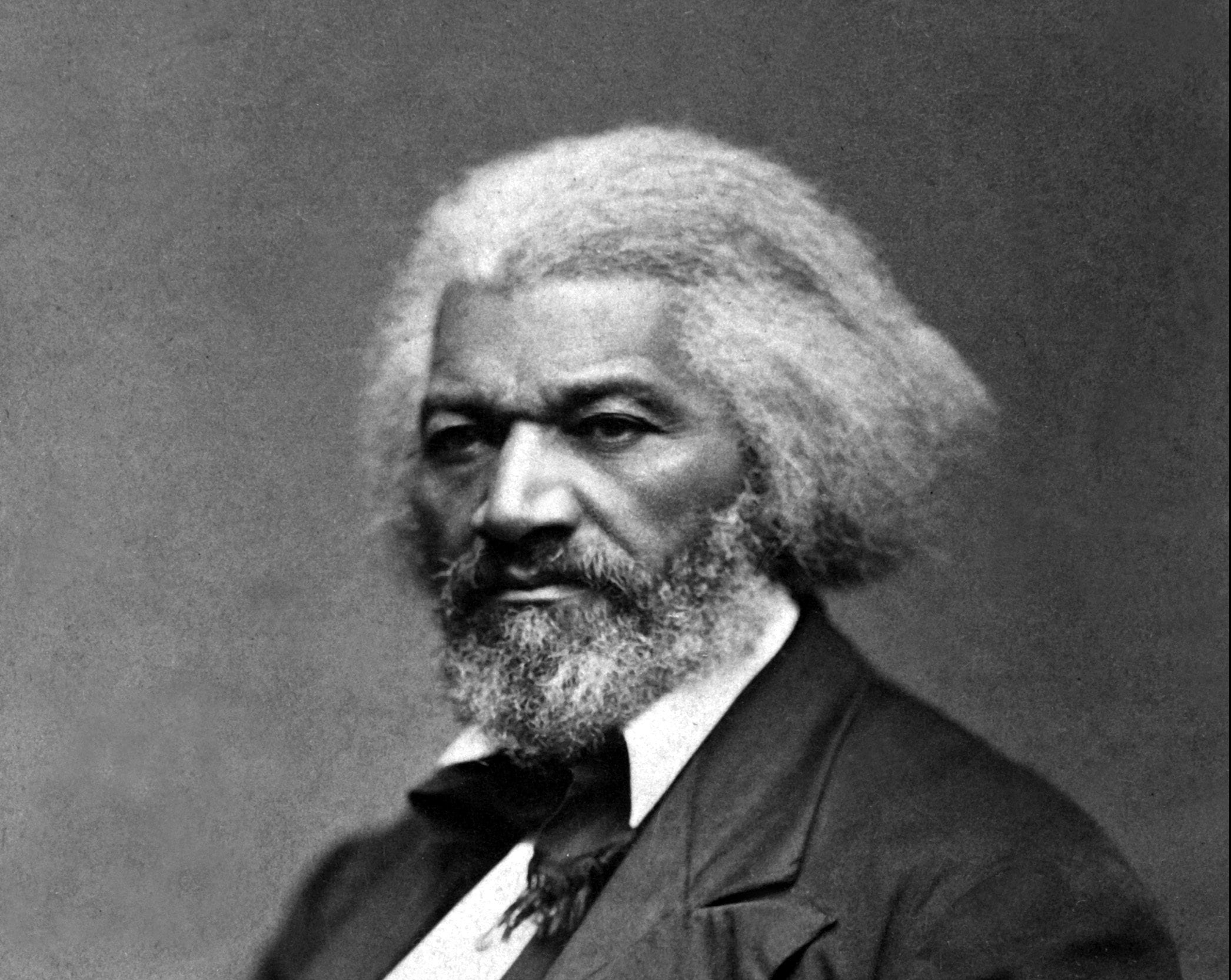

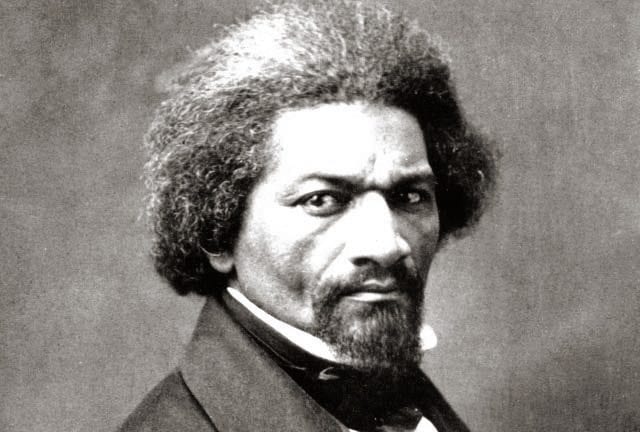

D. Frederick Douglass, “John Brown Not Insane,” November 1859

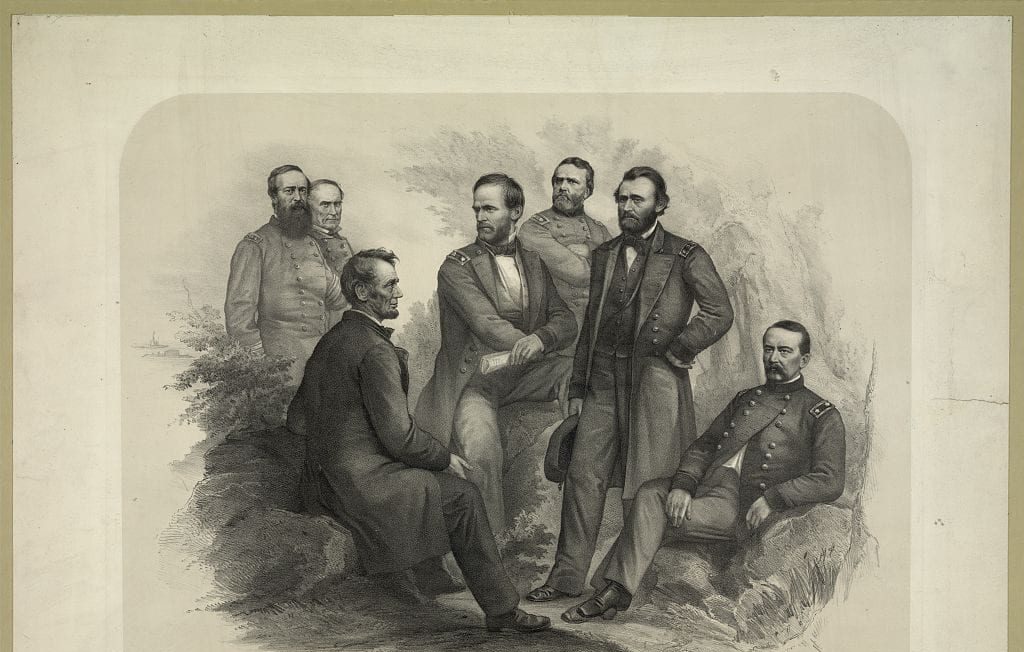

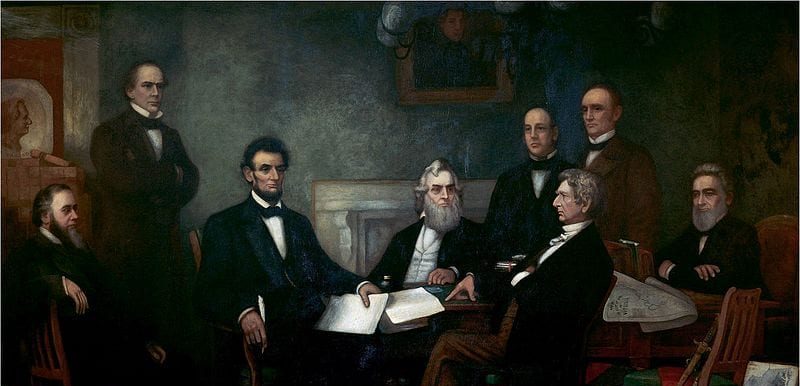

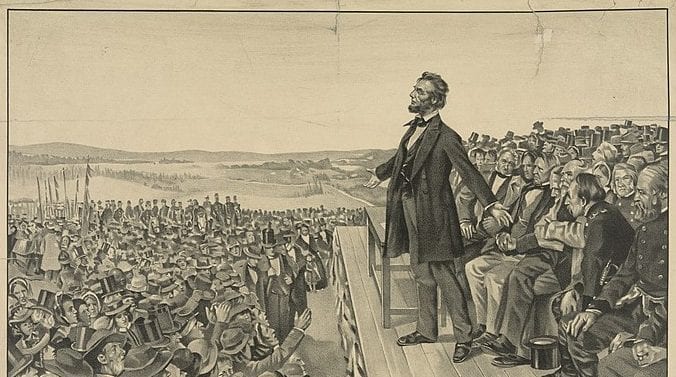

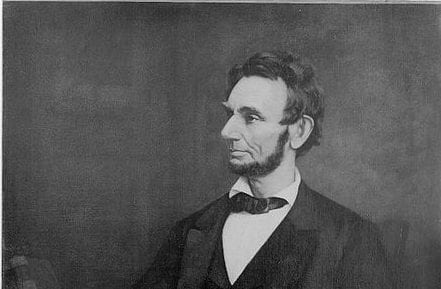

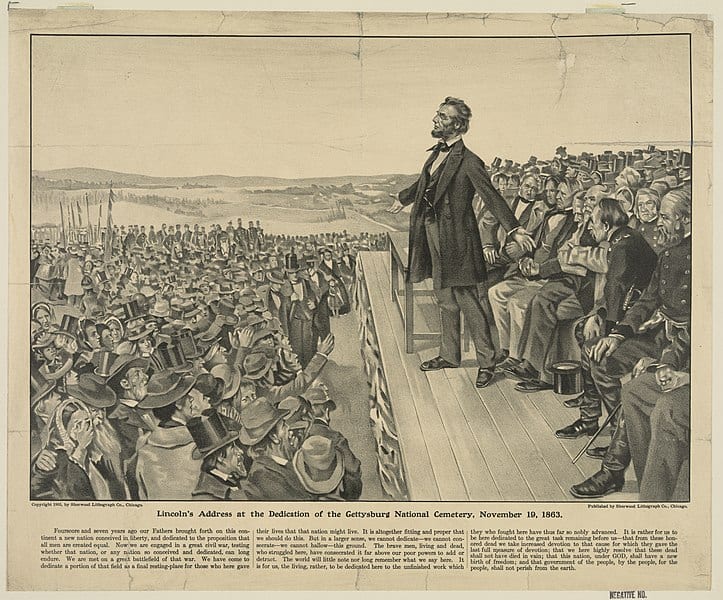

E. Abraham Lincoln, Cooper Union Address, February 27, 1860

F. William W. Patton, Lyrics to John Brown’s Body, December 16, 1861

Discussion Questions

A. Was Brown a martyr or a madman (or both?)? Was radical abolitionism (either rhetorically or in fact) either morally or constitutionally justifiable? When Lincoln suggests that John Brown’s raid was an aberration because the slaves did not lead it, what does he mean to suggest about the legitimacy (or illegitimacy) of such political activism?

B. As an example of politically motivated resistance, how might we compare Brown’s raid to the American Revolution or the Whiskey Rebellion? (Chapters 5 and 8)

C. How do you suppose Brown’s actions would have been evaluated in the atmosphere of heightened security-consciousness exemplified in Volume 2, Chapter 25?

A. Lydia Maria Child, Governor Henry Wise of Virginia, and John Brown, Correspondence, October 1859

Lydia Maria Child to Governor Henry A. Wise, October 26, 1859

Governor Wise,

I have heard that you were a man of chivalrous sentiments, and I know you were opposed to the iniquitous attempt to force upon Kansas a Constitution abhorrent to the moral sense of her people. Relying upon these indications of honor and justice in your character, I venture to ask a favor of you. Inclosed is a letter to Captain John Brown. Will you have the kindness, after reading it yourself, to transmit it to the prisoner?

I and all my large circle of abolition acquaintances were taken by surprise when news came of Captain Brown’s recent attempt; nor do I know of a single person who would have approved of it, had they been apprised of his intention. But I and thousands of others feel a natural impulse of sympathy for the brave and suffering man. Perhaps God, who sees the inmost of our souls, perceives some such sentiment in your heart also. He needs a mother or sister to dress his wounds, and speak soothingly to him. Will you allow me to perform that mission of humanity? If you will, may God bless you for the generous deed!

I have been for years an uncompromising abolitionist, and I should scorn to deny it or apologize for it as much as John Brown himself would do. Believing in peace principles, I deeply regret the step that the old veteran has taken, while I honor his humanity towards those who became his prisoners. But because it is my habit to be as open as the daylight, I will also say, that if I believed our religion justified men in fighting for freedom, I should consider the enslaved everywhere as best entitled to that right. Such an avowal is a simple, frank expression of my sense of natural justice.

But I should despise myself utterly if any circumstances could tempt me to seek to advance these opinions in any way, directly or indirectly, after your permission to visit Virginia has been obtained on the plea of sisterly sympathy with a brave and suffering man. I give you my word of honor, which was never broken, that I would use such permission solely and singly for the purpose of nursing your prisoner, and for no other purpose whatsoever.

Yours respectfully, L. Maria Child.

Governor Wise to L. Maria Child, October 29, 1859

Madam,

Yours of the 26th was received by me yesterday, and at my earliest leisure I respectfully reply to it, that I will forward the letter for John Brown, a prisoner under our laws, arraigned at the Circuit Court for the county of Jefferson, at Charlestown, Va., for the crimes of murder, robbery, and treason, which you ask me to transmit to him. I will comply with your request in the only way which seems to me proper, by inclosing it to the Commonwealth’s attorney, with the request that he will ask the permission of the court to hand it to the prisoner. Brown, the prisoner, is now in the hands of the judiciary, not of the executive, of this Commonwealth.

You ask me, further, to allow you to perform the mission “of mother or sister, to dress his wounds, and speak soothingly to him.” By this, of course, you mean to be allowed to visit him in his cell, and to minister to him in the offices of humanity. Why should you not be so allowed, Madam? Virginia and Massachusetts are involved in no civil war, and the Constitution which unites them in one confederacy guaranties to you the privileges and immunities of a citizen of the United States in the State of Virginia. That Constitution I am sworn to support, and am, therefore, bound to protect your privileges and immunities as a citizen of Massachusetts coming into Virginia for any lawful and peaceful purpose.

Coming, as you propose, to minister to the captive in prison, you will be met, doubtless, by all our people, not only in a chivalrous, but in a Christian spirit. You have the right to visit Charlestown, Va., Madam; and your mission, being merciful and humane, will not only be allowed, but respected, if not welcomed. A few unenlightened and inconsiderate persons, fanatical in their modes of thought and action to maintain justice and right, might molest you, or be disposed to do so; and this might suggest the imprudence of risking any experiment upon the peace of a society very much excited by the crimes with whose chief author you seem to sympathize so much. But still, I repeat, your motives and avowed purpose are lawful and peaceful, and I will, as far as I am concerned, do my duty in protecting your rights in our limits. Virginia and her authorities would be weak indeed—weak in point of folly, and weak in point of power—if her State faith and constitutional obligations cannot be redeemed in her own limits to the letter of morality as well as of law; and if her chivalry cannot courteously receive a lady’s visit to a prisoner, every arm which guards Brown from rescue on the one hand, and from lynch law on the other, will be ready to guard your person in Virginia.

I could not permit an insult even to woman in her walk of charity among us, though it be to one who whetted knives of butchery for our mothers, sisters, daughters, and babes. We have no sympathy with your sentiments of sympathy with Brown, and are surprised that you were “taken by surprise when news came of Captain Brown’s recent attempt.” His attempt was a natural consequence of your sympathy, and the errors of that sympathy ought to make you doubt its virtue from the effect on his conduct. But it is not of this I should speak. When you arrive at Charlestown, if you go there, it will be for the court and its officers, the Commonwealth’s attorney, sheriff and jailer, to say whether you may see and wait on the prisoner. But, whether you are thus permitted or not (and you will be, if my advice can prevail), you may rest assured that he will be humanely, lawfully, and mercifully dealt by in prison and on trial.

Respectfully, Henry A. Wise.

- Marie Child to Governor Wise, n.d.

In your civil but very diplomatic reply to my letter, you inform me that I have a constitutional right to visit Virginia, for peaceful purposes, in common with every citizen of the United States. I was perfectly well aware that such was the theory of constitutional obligation in the slave States; but I was also aware of what you omit to mention, viz.: that the Constitution has, in reality, been completely and systematically nullified, whenever it suited the convenience or the policy of the slave power. Your constitutional obligation, for which you profess so much respect, has never proved any protection to citizens of the free States who happened to have a black, brown, or yellow complexion; nor to any white citizen whom you even suspected of entertaining opinions opposite to your own, on a question of vast importance to the temporal welfare and moral example of our common country. This total disregard of constitutional obligation has been manifested not Merely by the lynch law of mobs in the slave States, but by the deliberate action of magistrates and legislators. . . . Slavery is, in fact, an infringement of all law, and adheres to no law, save for its own purposes of oppression.

You accuse Captain John Brown of “whetting knives of butchery for the mothers, sisters, daughters, and babes” of Virginia; and you inform me of the well-known fact, that he is “arraigned for the crimes of murder, robbery, and treason.” I will not here stop to explain why I believe that old hero to be no criminal, but a martyr to righteous principles which he sought to advance by methods sanctioned by his own religious views, though not by mine. Allowing that Captain Brown did attempt a scheme in which murder, robbery, and treason were, to his own consciousness, involved, I do not see how Governor Wise can consistently arraign him for crimes he has himself commended. You have threatened to trample on the Constitution, and break the Union, if a majority of the legal voters in these confederated States dared to elect a President unfavorable to the extension of slavery. Is not such a declaration proof of premeditated treason? In the spring of 1842 you made a speech in Congress, from which I copy the following:

Once set before the people of the great valley the conquest of the rich Mexican provinces, and you might as well attempt to stop the wind. This government might send its troops, but they would run over them like a herd of buffalo. Let the work once begin, and I do not know that this House would hold me very long. Give me five millions of dollars, and I would undertake to do it myself. Although I do not know how to set a single squadron in the field, I could find men to do it. Slavery should pour itself abroad, without restraint, and find no limit but the southern ocean. . . .

When you thus boasted that you and your “booted loafers” would overrun the troops of the United States “like a herd of buffalo,” if the government sent them to arrest your invasion of a neighboring nation, at peace with the United States, did you not pledge yourself to commit treason? Was it not by robbery, even of churches, that you proposed to load the mules of Mexico with gold for the United States? Was it not by the murder of unoffending Mexicans that you expected to advance those schemes of avarice and ambition? What humanity had you for Mexican “mothers and babes,” whom you proposed to make childless and fatherless? And for what purpose was this wholesale massacre to take place? Not to right the wrongs of any oppressed class; not to sustain any great principles of justice, or of freedom; but merely to enable “slavery to pour itself forth without restraint.”

. . . If Captain Brown intended, as you say, to commit treason, robbery, and murder, I think I have shown that he could find ample authority for such proceedings in the public declarations of Governor Wise. And if, as he himself declares, he merely intended to free the oppressed, where could he read a more forcible lesson than is furnished by the state seal of Virginia? I looked at it thoughtfully before I opened your letter; and though it had always appeared to me very suggestive, it never seemed to me so much so as it now did in connection with Captain John Brown. A liberty-loving hero stands with his foot upon a prostrate despot; under his strong arm, manacles and chains lie broken; and the motto is, “Sic Semper Tyrannis;” “Thus be it ever done to tyrants.” And this is the blazon of a State whose most profitable business is the internal slave-trade!—in whose highways coffles of human chattels, chained and manacled, are frequently seen! And the seal and the coffles are both looked upon by other chattels, constantly exposed to the same fate! What if some Vezey, or Nat Turner, should be growing up among those apparently quiet spectators? It is in no spirit of taunt or of exultation that I ask this question. I never think of it but with anxiety, sadness, and sympathy. I know that a slave-holding community necessarily lives in the midst of gunpowder; and, in this age, sparks of free thought are flying in every direction. You cannot quench the fires of free thought and human sympathy by any process of cunning or force; but there is a method by which you can effectually wet the gunpowder. England has already tried it, with safety and success. Would that you could be persuaded to set aside the prejudices of education, and candidly examine the actual working of that experiment! Virginia is so richly endowed by nature that free institutions alone are wanting to render her the most prosperous and powerful of the States.

In your letter you suggest that such a scheme as Captain Brown’s is the natural result of the opinions with which I sympathize. Even if I thought this to be a correct statement, though I should deeply regret it, I could not draw the conclusion that humanity ought to be stifled, and truth struck dumb, for fear that long-successful despotism might be endangered by their utterance. But the fact is, you mistake the source of that strange outbreak. No abolition arguments or denunciations, however earnestly, loudly, or harshly proclaimed, would have produced that result. It was the legitimate consequence of the continual and constantly-increasing aggressions of the slave power. The slave States, in their desperate efforts to sustain a bad and dangerous institution, have encroached more and more upon the liberties of the free States. Our inherent love of law and order, and our superstitious attachment to the Union, you have mistaken for cowardice; and rarely have you let slip any opportunity to add insult to aggression.

The manifested opposition to slavery began with the lectures and pamphlets of a few disinterested men and women, who based their movements upon purely moral and religious grounds; but their expostulations were met with a storm of rage, with tar and feathers, brickbats, demolished houses, and other applications of lynch law. When the dust of the conflict began to subside a little, their numbers were found to be greatly increased by the efforts to exterminate them. They had become an influence in the State too important to be overlooked by shrewd calculators. Political economists began to look at the subject from a lower point of view. They used their abilities to demonstrate that slavery was a wasteful system, and that the free States were taxed to an enormous extent to sustain an institution which, at heart, two thirds of them abhorred. The forty millions, or more, of dollars expended in hunting fugitive slaves in Florida, under the name of the Seminole War, were adduced, as one item of proof, to which many more were added. At last politicians were compelled to take some action on the subject. It soon became known to all the people that the slave States had always managed to hold in their hands the political power of the Union. . . .

Through these and other instrumentalities, the sentiments of the original Garrisonian abolitionists became very widely extended, in forms more or less diluted. But by far the most efficient co-laborers we have ever had have been the slave States themselves. By denying us the sacred right of petition, they roused the free spirit of the North as it never could have been roused by the loud trumpet of Garrison or the soul-animating bugle of Phillips. They bought the great slave, Daniel, and, according to their established usage, paid him no wages for his labor. By his cooperation they forced the Fugitive Slave Law upon us in violation of all our humane instincts and all our principles of justice. And what did they procure for the abolitionists by that despotic process? A deeper and wider detestation of slavery throughout the free States, and the publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” an eloquent outburst of moral indignation, whose echoes wakened the world to look upon their shame.

By filibustering and fraud they dismembered Mexico, and, having thus obtained the soil of Texas, they tried to introduce it as a slave State into the Union. Failing to effect their purpose by constitutional means, they accomplished it by a most open and palpable violation of the Constitution, and by obtaining the votes of senators on false pretenses.

Soon afterward a Southern slave administration ceded to the powerful monarchy of Great Britain several hundreds thousands of square miles that must have been made into free States, to which that same administration had declared that the United States had “an unquestionable right” and then they turned upon the weak republic of Mexico, and, in order to make more slave States, wrested from her twice as many hundred thousands of square miles, to which we had not a shadow of right.

Notwithstanding all these extra efforts, they saw symptoms that the political power so long held with a firm grasp was in danger of slipping from their hands, by reason of the extension of abolition sentiments, and the greater prosperity of free States. Emboldened by continual success in aggression, they made use of the pretense of “squatter sovereignty” to break the league into which they had formerly cajoled the servile representatives of our blinded people, by which all the territory of the United States south of 36° 300 was guaranteed to slavery, and all north of it to freedom. Thus Kansas became the battle-ground of the antagonistic elements in our government. Ruffians hired by the slave power were sent thither temporarily to do the voting and drive from the polls the legal voters, who were often murdered in the process. Names copied from the directories of cities in other States were returned by thousands as legal voters in Kansas, in order to establish a Constitution abhorred by the people. This was their exemplification of squatter sovereignty. A Massachusetts senator, distinguished for candor, courtesy, and stainless integrity, was half murdered by slave-holders merely for having the manliness to state these facts to the assembled Congress of the nation. Peaceful emigrants from the North, who went to Kansas for no other purpose than to till the soil, erect mills, and establish manufactories, schools, and churches, were robbed, outraged, and murdered. For many months a war more ferocious than the warfare of wild Indians was carried on against a people almost unresisting, because they relied upon the central government for aid. And all this while the power of the United States, wielded by the slave oligarchy, was on the side of the aggressors. This was the state of things when the hero of Ossawatomie and his brave sons went to the rescue. It was he who first turned the tide of border-ruffian triumph, by showing them that blows were to be taken as well as given.

You may believe it or not, Governor Wise, but it is certainly the truth that, because slave-holders so recklessly sowed the wind in Kansas, they reaped a whirlwind at Harpers Ferry.

The people of the North had a very strong attachment to the Union; but by your desperate measures you have weakened it beyond all power of restoration. They are not your enemies, as you suppose, but they cannot consent to be your tools for any ignoble task you may choose to propose. . . . A majority of them would rejoice to have the slave States fulfill their oft-repeated threat of withdrawal from the Union. It has ceased to be a bugbear, for we begin to despair of being able, by any other process, to give the world the example of a real republic. The moral sense of these States is outraged by being accomplices in sustaining an institution vicious in all its aspects; and it is now generally understood that we purchase our disgrace at great pecuniary expense. If you would only make the offer of a separation in serious earnest, you would hear the hearty response of millions,

Go, gentlemen, and Stand not upon the order of your going, But go at once!

Yours, with all due respect, L. Maria Child.

- Marie Child to John Brown, October 26, 1859

Dear Captain Brown: Though personally unknown to you, you will recognize in my name an earnest friend of Kansas, when circumstances made that Territory the battle-ground between the antagonistic principles of slavery and freedom, which politicians so vainly strive to reconcile in the government of the United States.

Believing in peace principles, I cannot sympathize with the method you chose to advance the cause of freedom. But I honor your generous intentions,—I admire your courage, moral and physical. I reverence you for the humanity which tempered your zeal. I sympathize with you in your cruel bereavement, your sufferings, and your wrongs. In brief, I love you and bless you.

Thousands of hearts are throbbing with sympathy as warm as mine. I think of you night and day, bleeding in prison, surrounded by hostile faces, sustained only by trust in God and your own strong heart. I long to nurse you—to speak to you sisterly words of sympathy and consolation. I have asked permission of Governor Wise to do so. If the request is not granted, I cherish the hope that these few words may at least reach your hands, and afford you some little solace. May you be strengthened by the conviction that no honest man ever sheds blood for freedom in vain, however much he may be mistaken in his efforts. May God sustain you, and carry you through whatsoever may be in store for you! Yours, with heartfelt respect, sympathy and affection,

- Maria Child.

Reply of John Brown

Mrs. L. Maria Child:

My dear friend,

Such you prove to be, though a stranger,—your most kind letter has reached me, with the kind offer to come here and take care of me. Allow me to express my gratitude for your great sympathy, and at the same time to propose to you a different course, together with my reasons for wishing it. I should certainly be greatly pleased to become personally acquainted with one so gifted and so kind, but I cannot avoid seeing some objections to it, under present circumstances. First, I am in charge of a most humane gentleman, who, with his family, has rendered me every possible attention I have desired, or that could be of the least advantage; and I am so recovered of my wounds as no longer to require nursing. Then, again, it would subject you to great personal inconvenience and heavy expense, without doing me any good. . . .

I am quite cheerful under all my afflicting circumstances and prospects; having, as I humbly trust, “the peace of God which passeth all understanding” to rule in my heart. You may make such use of this as you see fit. God Almighty bless and reward you a thousand fold

Yours in sincerity and truth, John Brown.

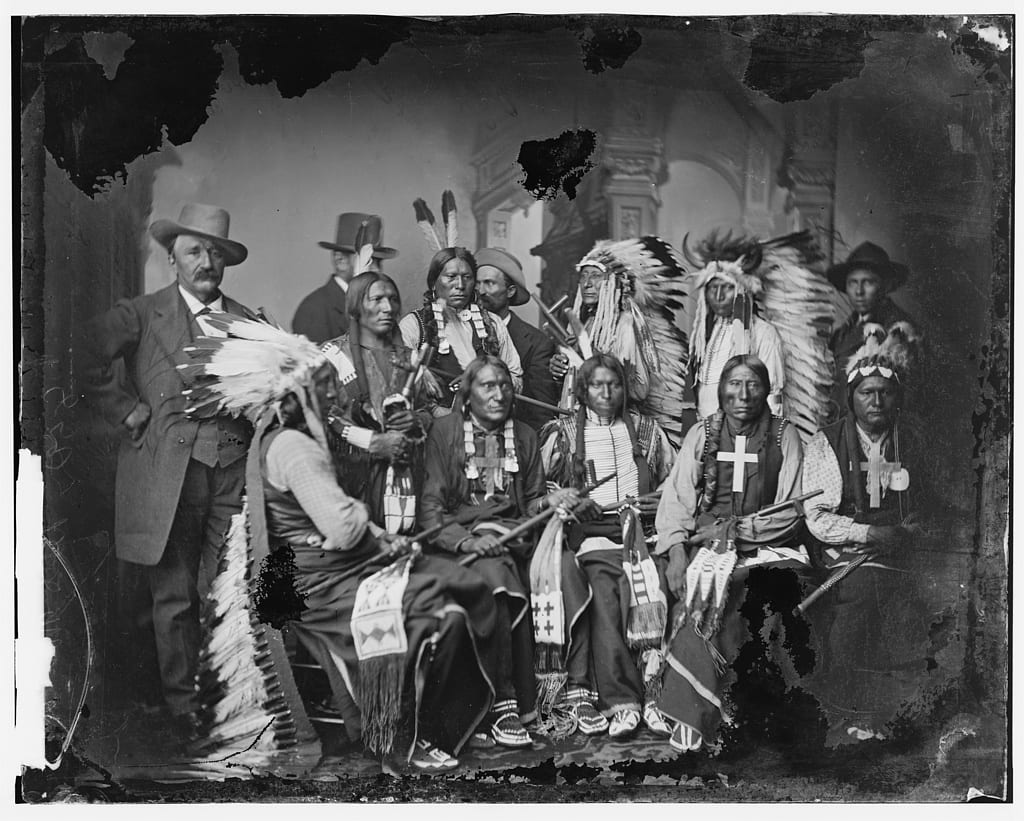

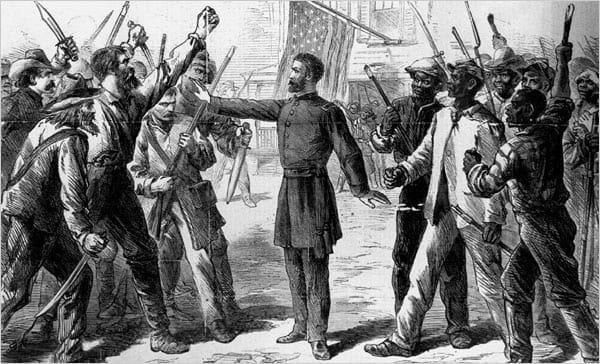

B. D. H. Strother, A Southern Planter Arming His Slaves to Resist Invasion, November 19, 1859

See illustration on page 142.

C. Horace Greeley, “The Whole Affair Seems the Work of a Madman,” October 19, 1859

The insurrection, so called, at Harpers Ferry, proves a verity. Old Brown of Osawatamie, who was last heard of on his way from Missouri to Canada with a band of runaway slaves, now turns up in Virginia, where he seems to have been for some months plotting and preparing for a general stampede of slaves. How he came to be in Harpers Ferry, and in possession of the U. S. Armory, is not yet clear; but he was probably betrayed or exposed, and seized the Armory as a place of security until he could safely get away. The whole affair seems the work of a madman; but John Brown has so often looked death serenely in the face that what seems madness to others doubtless wore a different aspect to him. He had twenty-one men with him, mostly white, who appear to have held the Armory from 9 P. M. of Sunday till 7 of Tuesday (yesterday) morning, when it was stormed by Col. Lee and a party of U. S. Marines, and its defenders nearly all killed or mortally wounded . . . . Of the original twenty-two, fifteen were killed, two mortally wounded, and two unhurt. The other three had pushed northward on Monday morning guiding a number of fugitive slaves through Maryland. These were of course sharply pursued and fired on, but had not been taken at our last advices. . . .

There will be enough to heap execration on the memory of these mistaken men. We leave this work to the fit hands and tongues of those who regard the fundamental axioms of the Declaration of Independence as “glittering generalities.” Believing that the way to Universal Emancipation lies not through insurrection, civil war and bloodshed, but through discussion, and the quick diffusion of sentiments of humanity and justice, we deeply regret this outbreak; but remembering that, if their fault was grievous, grievously have they answered it, we will not, by one reproachful word, disturb the bloody shrouds wherein John Brown and his compatriots are sleeping. They dared and died for what they felt to be the right, though in a manner which seems to us fatally wrong. Let their epitaphs remain unwritten until the not distant day when no slave shall clank his chains in the shades of Monticello or by the graves of Mount Vernon.

D. Frederick Douglass, “John Brown Not Insane,” November 1859

One of the most painful incidents connected with the name of this old hero is the attempt to prove him insane. Many journals have contributed to this effort from a friendly desire to shield the prisoner from Virginia’s cowardly vengeance. This is a mistaken friendship, which seeks to rob him of his true character and dim the glory of his deeds, in order to save his life. Was there the faintest hope of securing his release by this means, we would choke down our indignation and be silent. But a Virginia court would hang a crazy man without a moment’s hesitation, if his insanity took the form of hatred of oppression; and this plea only blasts the reputation of this glorious martyr of liberty, without the faintest hope of improving his chance of escape.

It is an appalling fact in the history of the American people, that they have so far forgotten their own heroic age, as readily to accept the charge of insanity against a man who has imitated the heroes of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill.

It is an effeminate and cowardly age, which calls a man a lunatic because he rises to such self-forgetful heroism, as to count his own life worth nothing in comparison with the freedom of millions of his fellows. Such an age would have sent Gideon to a mad-house and put Leonidas in a strait-jacket. Such a people would have treated the defenders of Thermopylae as demented, and shut up Caius Marcus in bedlam. Such a marrowless population as ours has become under the debaucheries of Slavery, would have struck the patriot’s crown from the brow of Wallace, and recommended blisters and bleeding to the heroic Tell. Wallace was often and again as desperately forgetful of his own life in defense of Scotland’s freedom, as was Brown in striking for the American slave; and Tell’s defiance of the Austrian tyrant was as far above the appreciation of cowardly selfishness, as was Brown’s defiance of the Virginia pirates. . . . Posterity will owe everlasting thanks to John Brown for lifting up once more to the gaze of a nation grown fat and flabby on the garbage of lust and oppression, a true standard of heroic philanthropy, and each coming generation will pay its installment of the debt. No wonder that the aiders and abettors of the huge, overshadowing and many-armed tyranny, which he grappled with in its own infernal den, should call him a mad man; but for those who profess a regard for him, and for human freedom, to join in the cruel slander “is the unkindest cut of all.”

Nor is it necessary to attribute Brown’s deeds to the spirit of vengeance invoked by the murder of his brave boys. That the barbarous cruelty from which he has suffered had its effect in intensifying his hatred of slavery, is doubtless true. But his own statement, that he had been contemplating a bold strike for the freedom of the slaves for ten years, proves that he had resolved upon his present course long before he, or his sons, ever set foot in Kansas. His entire procedure in this matter disproves the charge that he was prompted by an impulse of mad revenge, and shows that he was moved by the highest principles of philanthropy. His carefulness of the lives of unarmed persons—his humane and courteous treatment of his prisoners—his cool self-possession all through his trial—and especially his calm, dignified speech on receiving his sentence, all conspire to show that he was neither insane or actuated by vengeful passion; and we hope that the country has heard the last of John Brown’s madness.

The explanation of his conduct is perfectly natural and simple on its face. He believes the Declaration of Independence to be true, and the Bible to be a guide to human conduct, and acting upon the doctrines of both, he threw himself against the serried ranks of American oppression, and translated into heroic deeds the love of liberty and hatred of tyrants, with which he was inspired from both these forces acting upon his philanthropic and heroic soul. This age is too gross and sensual to appreciate his deeds, and so calls him mad; but the future will write his epitaph upon the hearts of a people freed from slavery, because he struck the first effectual blow.

Not only is it true that Brown’s whole movement proves him perfectly sane and free from merely revengeful passion, but he has struck the bottom line of the philosophy which underlies the abolition movement. He has attacked slavery with the weapons precisely adapted to bring it to the death. Moral considerations have long since been exhausted upon slaveholders. It is in vain to reason with them. One might as well hunt bears with ethics and political economy for weapons as to seek to “pluck the spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor” by the mere force of moral law. Slavery is a system of brute force. It shields itself behind might, rather than right. It must be met with its own weapons. Capt. Brown has initiated a new mode of carrying on the crusade of freedom, and his blow has sent dread and terror throughout the entire ranks of the piratical army of slavery. His daring deeds may cost him his life, but priceless as is the value of that life, the blow he has struck will, in the end, prove to be worthy its mighty cost. Like Samson, he has laid his hands upon the pillars of this great national temple of cruelty and blood, and when he falls, that temple will speedily crumple to its final doom, burying its denizens in its ruins.

E. Abraham Lincoln, Cooper Union Address, February 27, 1860

. . . I would address a few words to the Southern people. . . .

You charge that we stir up insurrections among your slaves. We deny it; and what is your proof? Harpers Ferry! John Brown!! . . .

Some of you admit that no Republican designedly aided or encouraged the Harpers Ferry affair; but still insist that our doctrines and declarations necessarily lead to such results. We do not believe it. . . .

Slave insurrections are no more common now than they were before the Republican party was organized. What induced the Southampton insurrection, twenty-eight years ago, in which, at least, three times as many lives were lost as at Harpers Ferry? . . . In the present state of things in the United States, I do not think a general, or even a very extensive slave insurrection, is possible. The indispensable concert of action cannot be attained. The slaves have no means of rapid communication; nor can incendiary freemen, black or white, supply it. . . .

Much is said by Southern people about the affection of slaves for their masters and mistresses; and a part of it, at least, is true. A plot for an uprising could scarcely be devised and communicated to twenty individuals before some one of them, to save the life of a favorite master or mistress, would divulge it. . . . Occasional poisonings from the kitchen, and open or stealthy assassinations in the field, and local revolts extending to a score or so, will continue to occur as the natural results of slavery; but no general insurrection of slaves, as I think, can happen in this country for a long time. Whoever much fears, or much hopes for such an event, will be alike disappointed. . . .

John Brown’s effort was peculiar. It was not a slave insurrection. It was an attempt by white men to get up a revolt among slaves, in which the slaves refused to participate. In fact, it was so absurd that the slaves, with all their ignorance, saw plainly enough it could not succeed. That affair, in its philosophy, corresponds with the many attempts, related in history, at the assassination of kings and emperors. An enthusiast broods over the oppression of a people till he fancies himself commissioned by Heaven to liberate them. He ventures the attempt, which ends in little else than his own execution. . . . .

F. William W. Patton, Lyrics to John Brown’s Body, 1861

Old John Brown’s body lies moldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But tho he lost his life while struggling for the slave,

His soul is marching on.

John Brown was a hero, undaunted, true and brave,

And Kansas knows his valor when he fought her rights to save;

Now, tho the grass grows green above his grave,

His soul is marching on.

He captured Harpers Ferry, with his nineteen men so few,

And frightened “Old Virginny” till she trembled thru and thru;

They hung him for a traitor, themselves the traitor crew,

But his soul is marching on.

John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see,

Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be,

And soon thruout the Sunny South the slaves shall all be free,

For his soul is marching on.

The conflict that he heralded he looks from heaven to view,

On the army of the Union with its flag red, white and blue.

And heaven shall ring with anthems o’er the deed they mean to do,

For his soul is marching on.

Ye soldiers of Freedom, then strike, while strike ye may,

The death blow of oppression in a better time and way,

For the dawn of old John Brown has brightened into day,

And his soul is marching on.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.