No related resources

Introduction

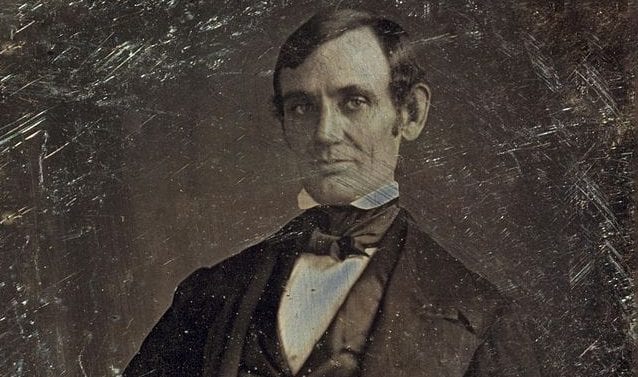

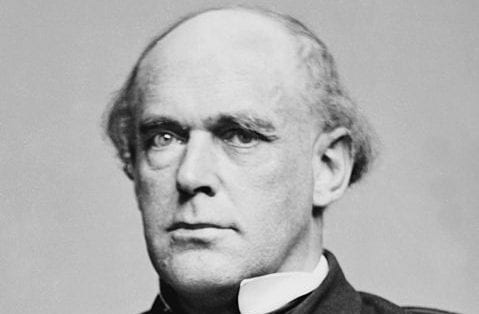

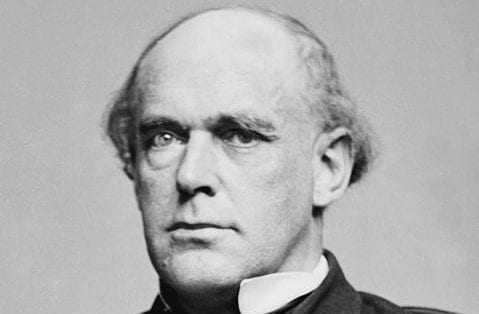

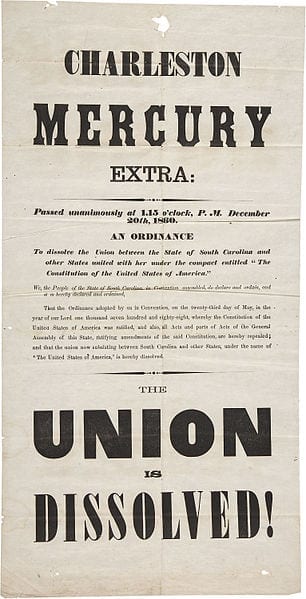

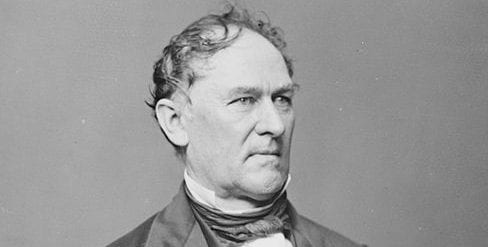

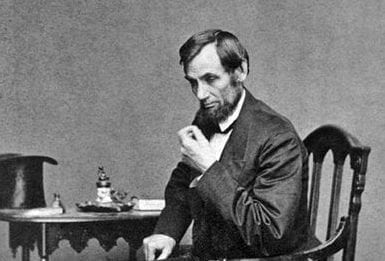

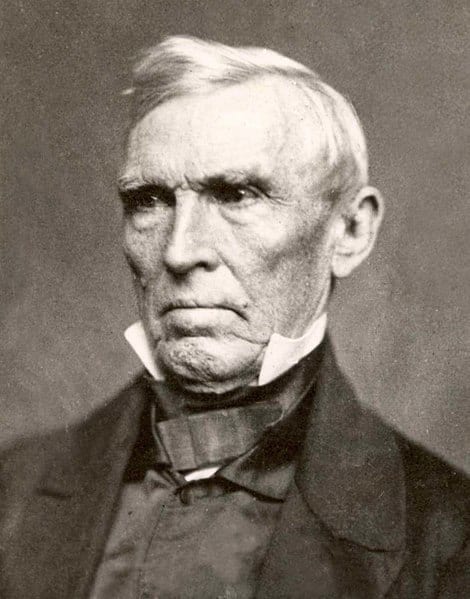

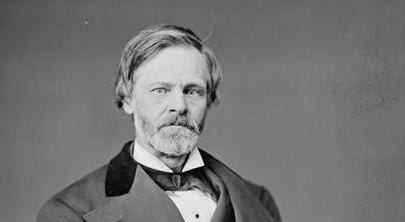

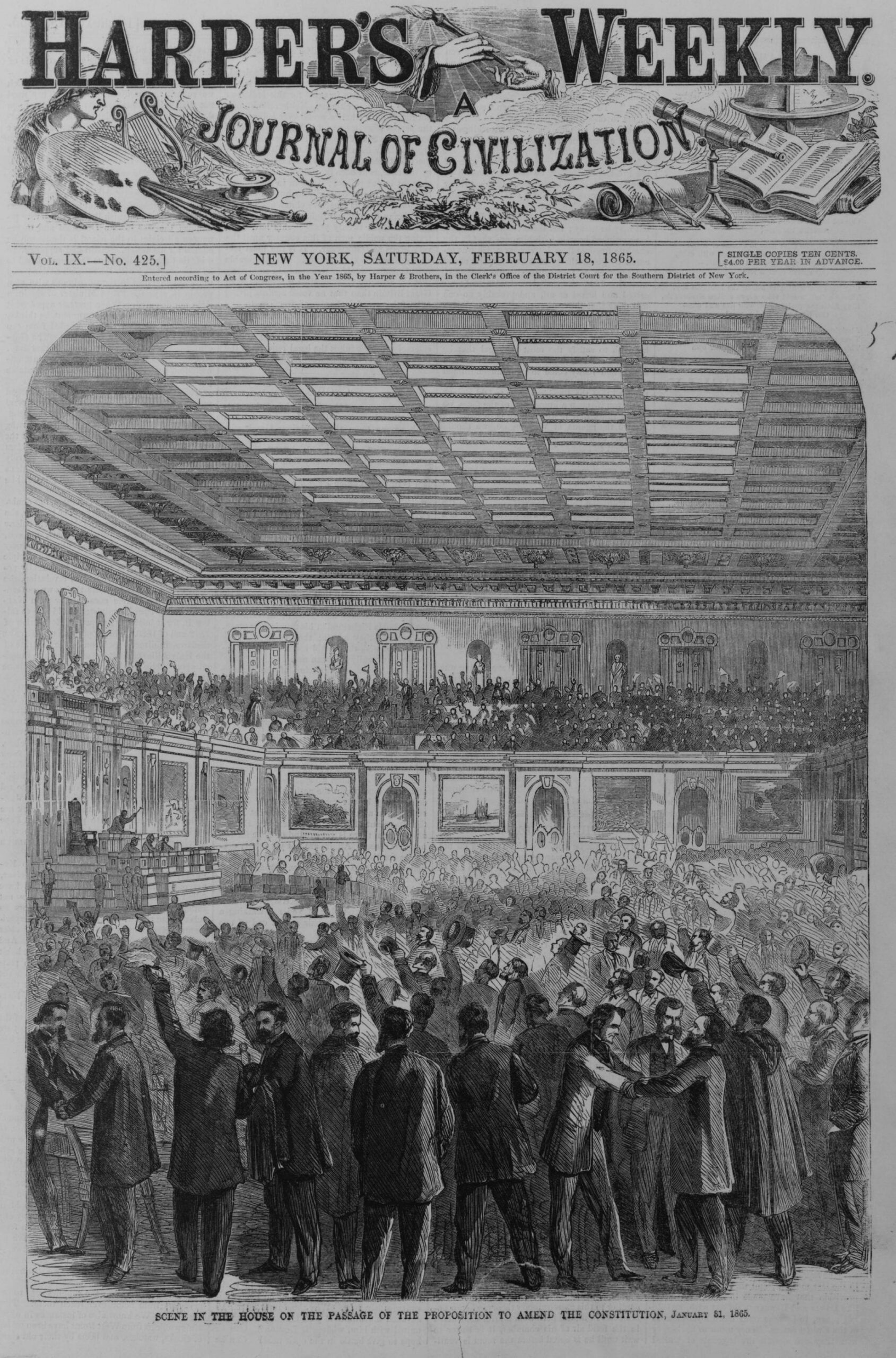

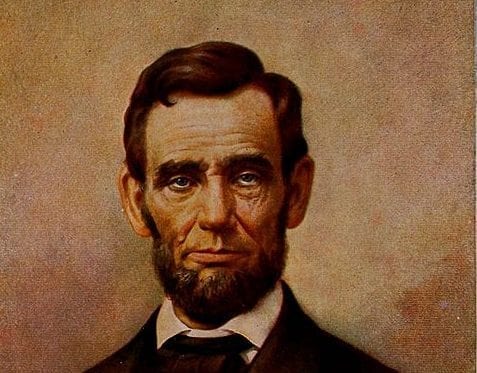

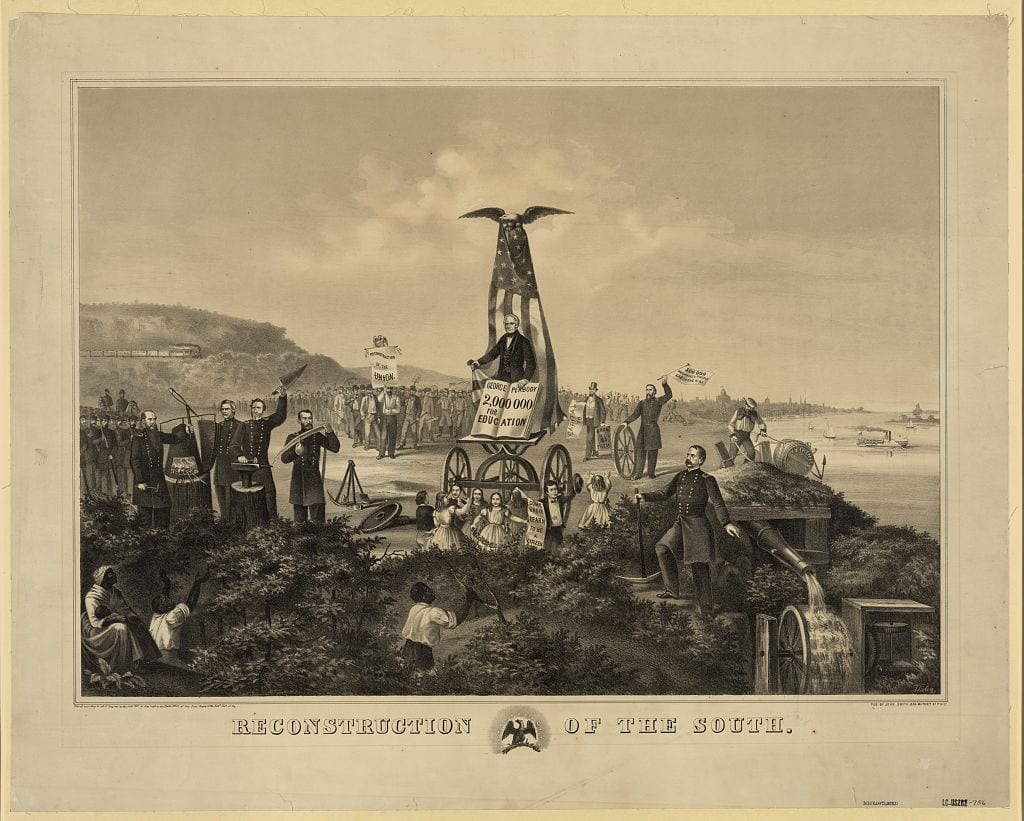

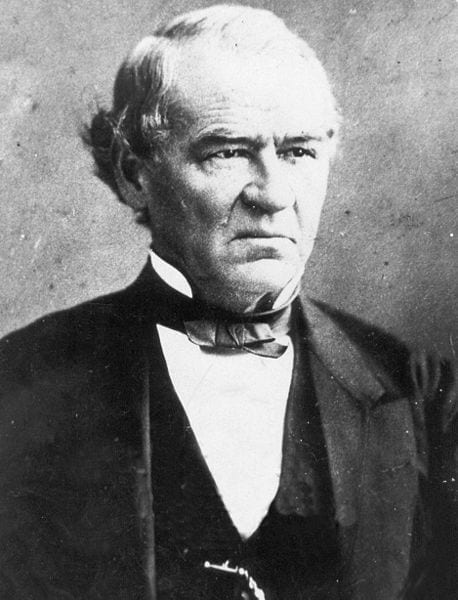

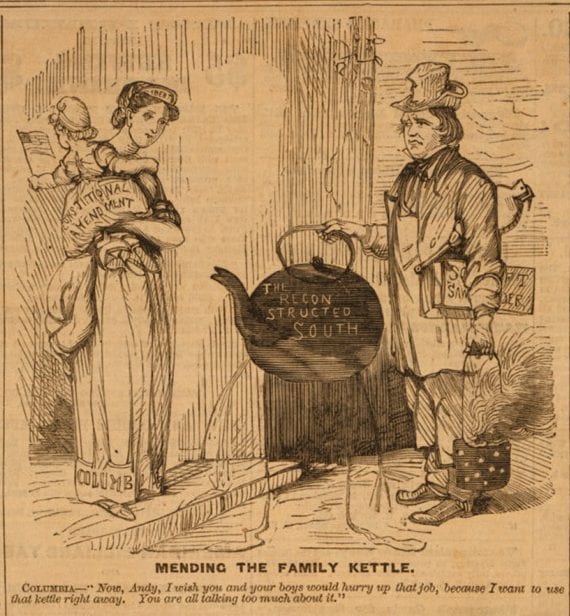

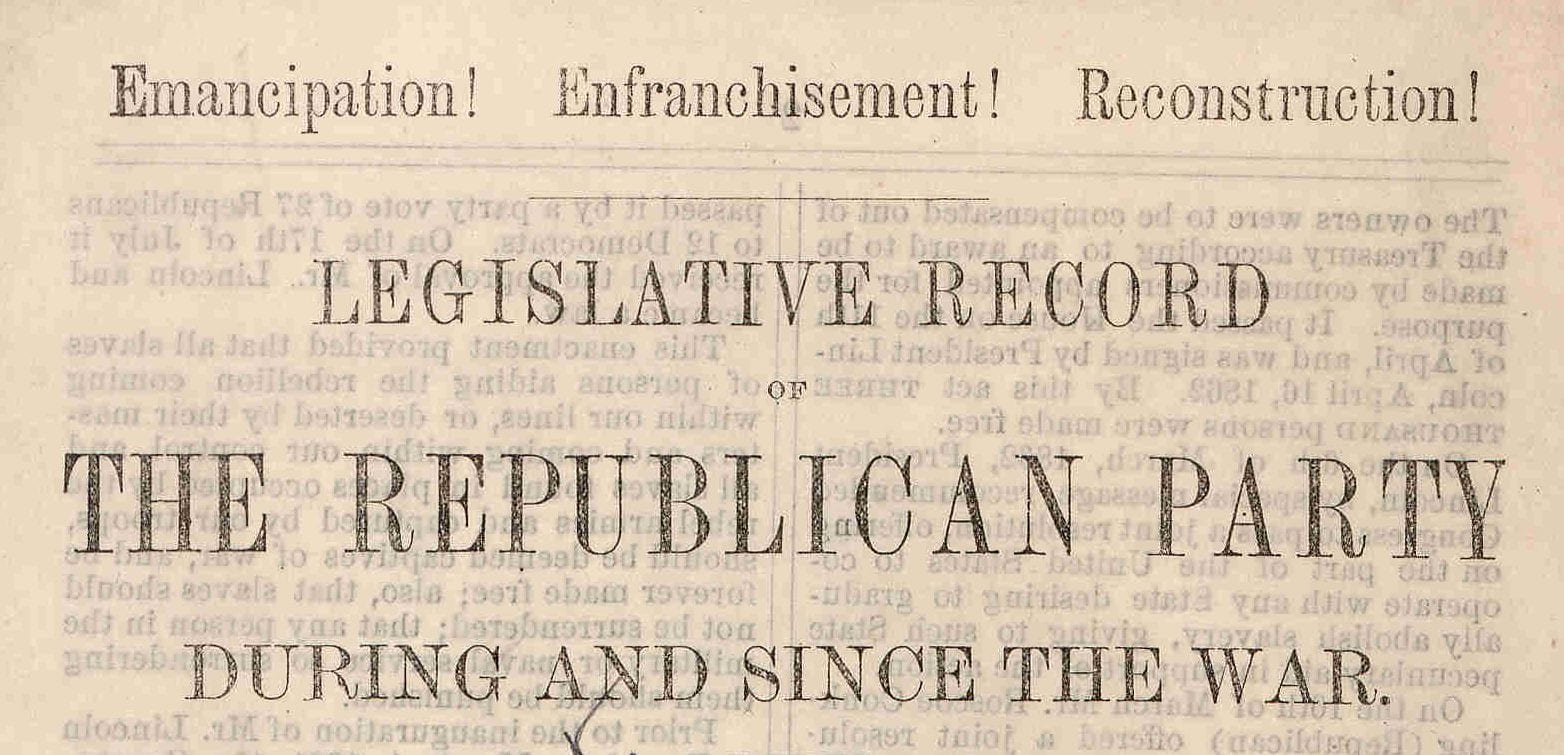

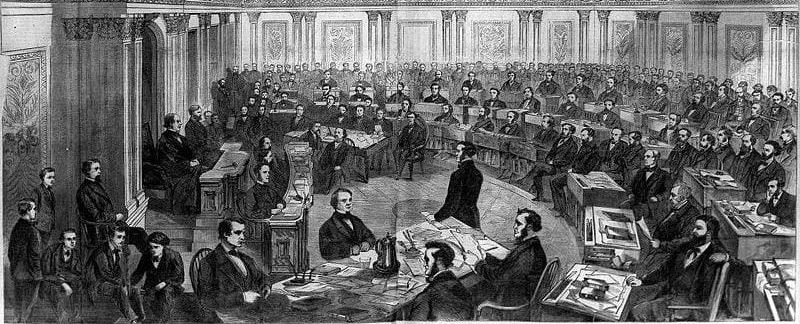

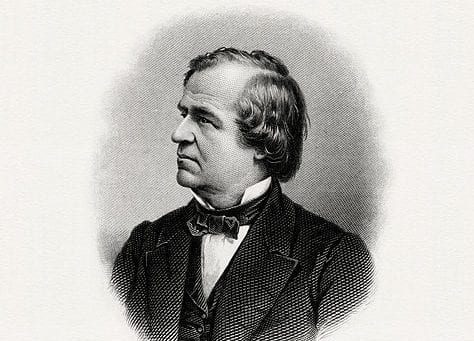

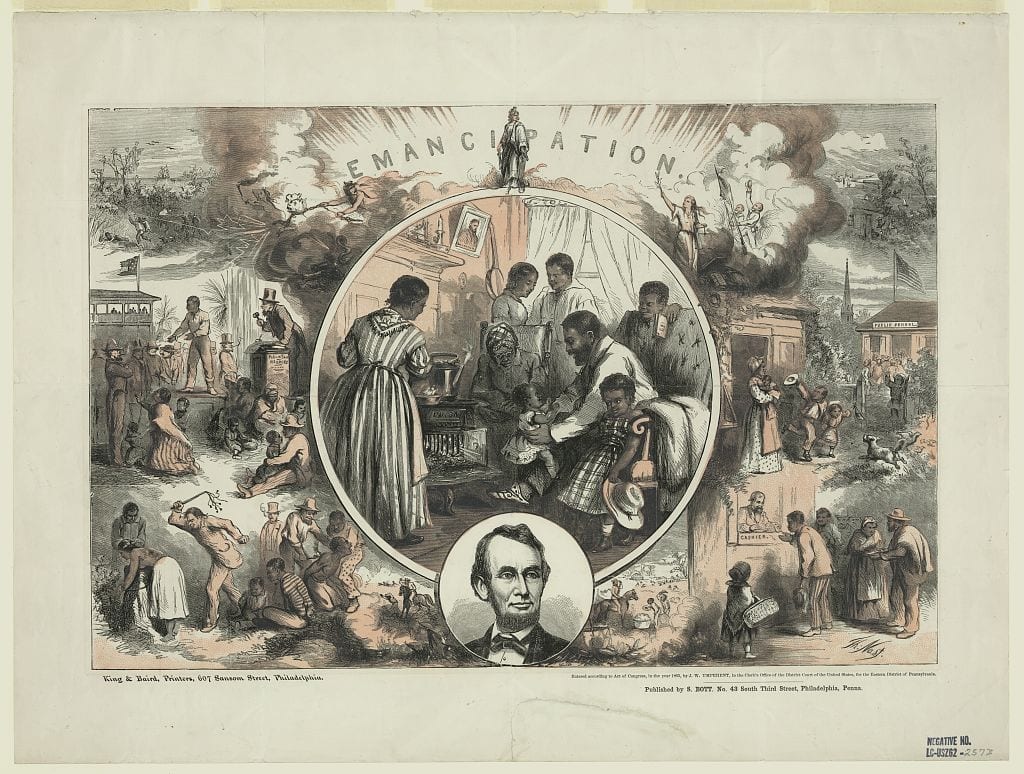

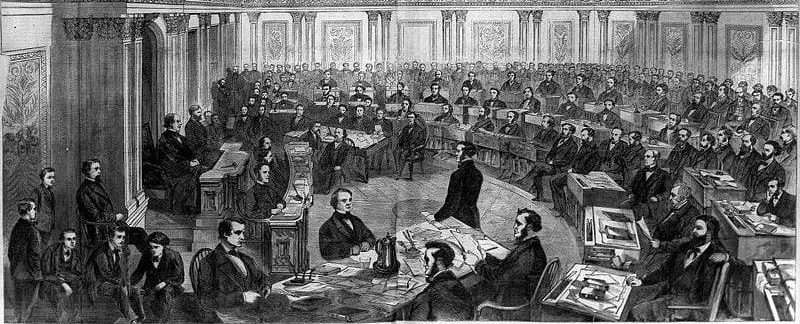

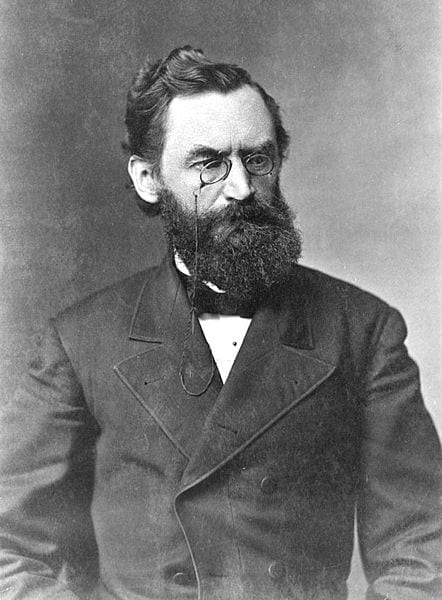

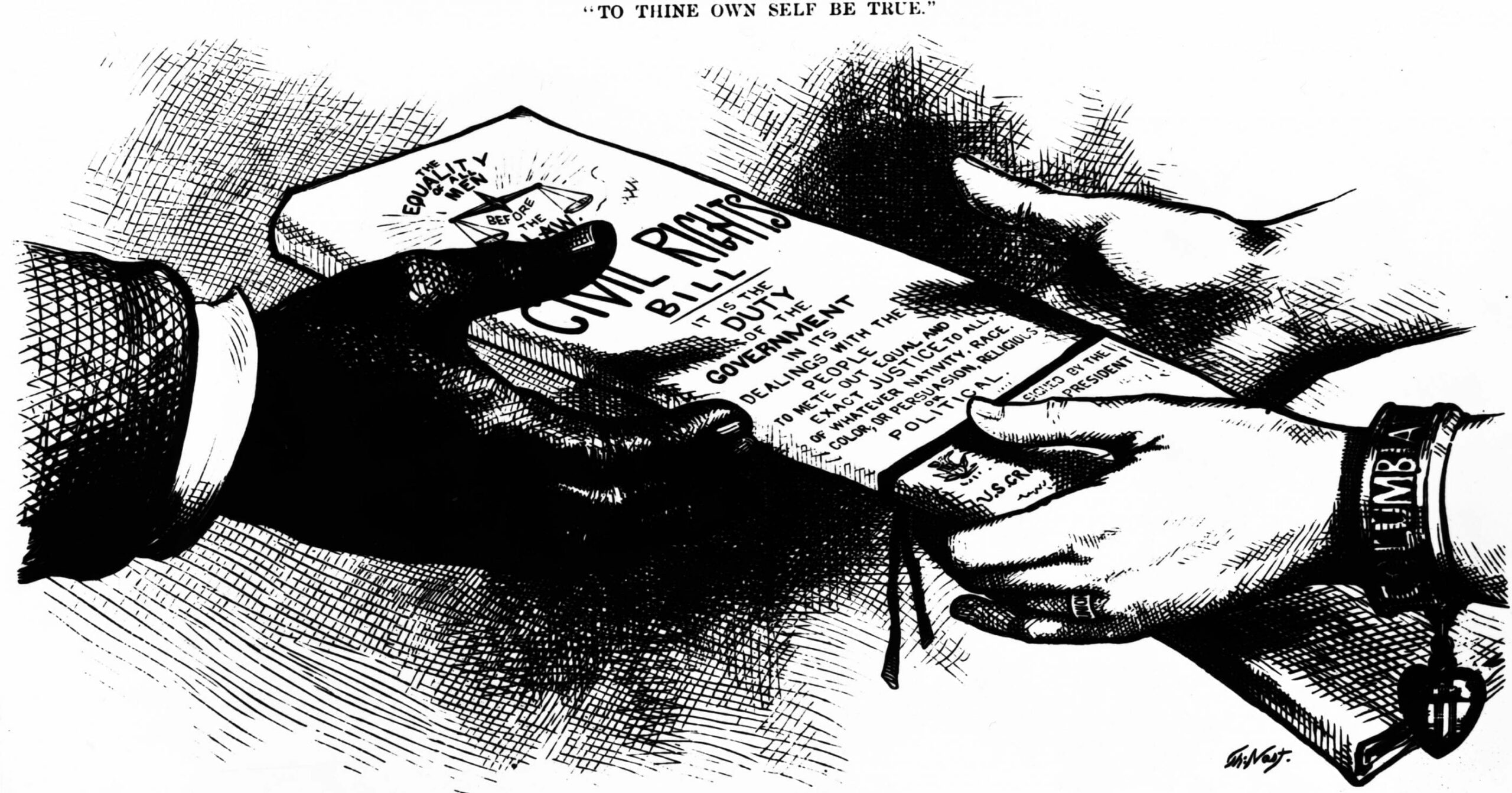

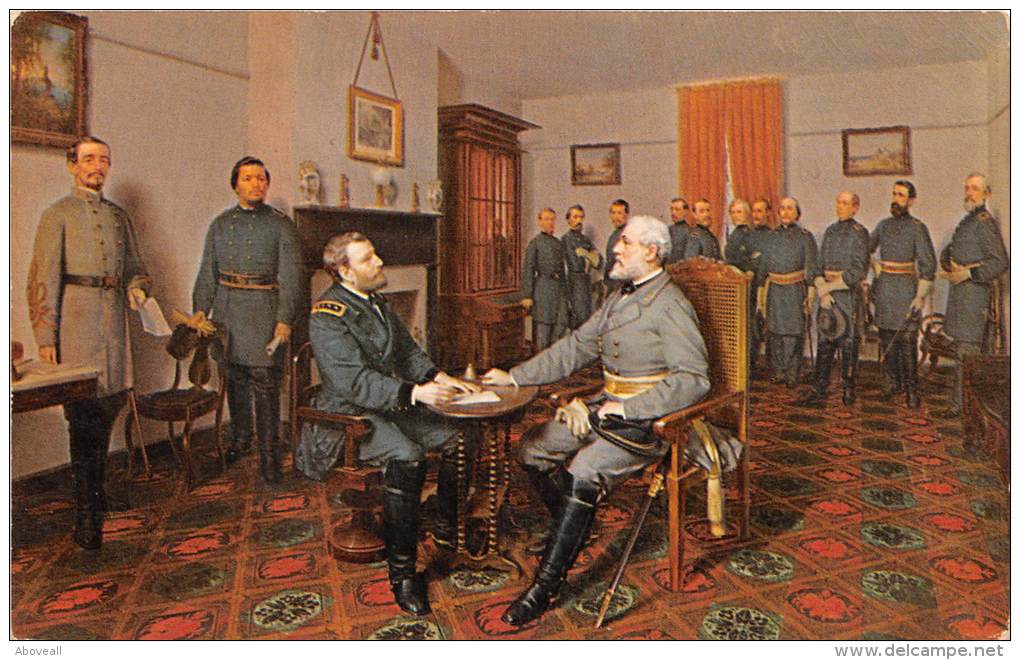

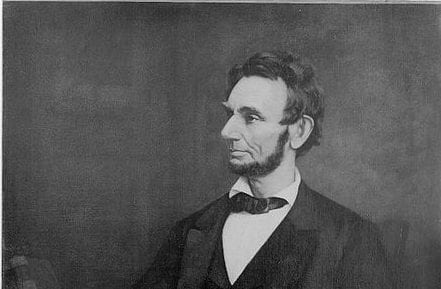

After the Civil War, Congress created a Joint Committee on Reconstruction charged with making recommendations regarding the treatment of southern states that had been members of the Confederate States of America. Pursuant to this charge, and in part with the intent of providing constitutional authority and protection for the recently enacted Civil Rights Act of 1866, the committee drafted the Fourteenth Amendment. Senator Jacob M. Howard (R-MI, 1805–1871) introduced the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment on behalf of the committee in a speech on the Senate floor on May 23, 1866.

Senator Howard discussed at length the first clause of the first provision of the amendment—“No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States”—which he regarded “as very important.” He took note of a similar provision in Article IV of the U.S. Constitution, which declares: “The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.” The U.S. Supreme Court had not defined “privileges and immunities,” but Howard quoted from the opinion of Justice Bushrod Washington in Corfield v. Coryell (1823), a case Washington decided while sitting as a circuit court judge, as offering insight. Justice Washington concluded that this clause protects rights that are “fundamental, which belong of right to the citizens of all free governments, and which have at all times been enjoyed by the citizens of the several states which compose this Union from the time of their becoming free, independent, and sovereign.” After listing a number of rights, Justice Washington concluded: “These, and many others which might be mentioned, are, strictly speaking, privileges and immunities.”

Senator Howard made clear that the purpose of the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, and the “privileges or immunities” clause in the amendment’s first section, was to require state governments to protect these rights and to authorize Congress to guarantee their protection. Currently, he argued, this “mass of privileges, immunities, and rights,” was not enforceable against state governments. The purpose of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment was to compel the states “at all times to respect these great fundamental guarantees.”

The Supreme Court has had many opportunities to interpret and apply the Fourteenth Amendment. In the years immediately following the amendment’s passage, the Court interpreted its guarantees narrowly (Justice Samuel F. Miller, Slaughter-House Cases, April 14, 1873 and Justice Joseph Bradley, Civil Rights Cases, October 15, 1883) and in a way that limited the Court’s reliance on the “privileges or immunities” clause to overturn state legislation. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, the Court has relied heavily on the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses to invalidate state laws and practices (Justice John Marshall Harlan II, Introduction to an Essay on Robert H. Jackson’s Influence on Federal-State Relationships).

Source: Senator Jacob Howard, Speech introducing the 14th Amendment, May 23, 1866, Congressional Globe, Senate, 39th Congress, 1st Session, 2764–2766, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llcg&fileName=072/llcg072.db&recNum=845.

... The section of the amendment they have submitted for the consideration of the two houses relates to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the several states, and to the rights and privileges of all persons, whether citizens or others, under the laws of the United States. It declares that—

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

It will be observed that this is a general prohibition upon all the states, as such, from abridging the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the United States. That is its first clause, and I regard it as very important. It also prohibits each one of the states from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying to any person within the jurisdiction of the state the equal protection of its laws.

The first clause of this section relates to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States as such, and as distinguished from all other persons not citizens of the United States. It is not, perhaps, very easy to define with accuracy what is meant by the expression, “citizen of the United States,” although that expression occurs twice in the Constitution, once in reference to the president of the United States, in which instance it is declared that none but a citizen of the United States shall be president, and again in reference to senators, who are likewise to be citizens of the United States. Undoubtedly the expression is used in both instances in the same sense in which it is employed in the amendment now before us. A citizen of the United States is held by the courts to be a person who was born within the limits of the United States and subject to their laws. Before the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, the citizens of each state were, in a qualified sense at least, aliens to one another, for the reason that the several states before that event were regarded by each other as independent governments, each one possessing a sufficiency of sovereign power to enable it to claim the right of naturalization; and, undoubtedly, each one of them possessed for itself the right of naturalizing foreigners, and each one, also, if it had seen fit to exercise its sovereign power, might have declared the citizens of every other state to be aliens in reference to itself. With a view to prevent such confusion and disorder, and to put the citizens of the several states on an equality with each other as to all fundamental rights, a clause was introduced in the Constitution declaring that “the citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.”

The effect of this clause was to constitute ipso facto1 the citizens of each one of the original states citizens of the United States. And how did they antecedently become citizens of the several states? By birth or by naturalization. They become such in virtue of national law, or rather the natural law which recognizes persons born within the jurisdiction of every country as being subjects or citizens of that country. Such persons were, therefore, citizens of the United States as were born in the country or were made such by naturalization; and the Constitution declares that they are entitled, as citizens, to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states. They are, by constitutional right, entitled to these privileges and immunities, and may assert this right and these privileges and immunities, and ask for their enforcement whenever they go within the limits of the several states of the Union.

It would be a curious question to solve what are the privileges and immunities of citizens of each of the states in the several states. I do not propose to go at any length into that question at this time. It would be a somewhat barren discussion. But it is certain the clause was inserted in the Constitution for some good purpose. It has in view some results beneficial to the citizens of the several states, or it would not be found there; yet I am not aware that the Supreme Court have ever undertaken to define either the nature or extent of the privileges and immunities thus guaranteed. Indeed, if my recollection serves me, that court, on a certain occasion not many years since, when this question seemed to present itself to them, very modestly declined to go into a definition of them, leaving questions arising under the clause to be discussed and adjudicated when they should happen practically to arise. But we may gather some intimation of what probably will be the opinion of the judiciary by referring to a case adjudged many years ago in one of the circuit courts of the United States by Judge Washington; and I will trouble the Senate but for a moment by reading what that very learned and excellent judge says about these privileges and immunities of the citizens of each state in the several states. It is the case of Corfield vs. Coryell ... Judge Washington says:

The next question is whether this act infringes that section of the Constitution which declares that “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States?”

The inquiry is, what are the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states? We feel no hesitation in confining these expressions to those privileges and immunities which are in their nature fundamental, which belong of right to the citizens of all free governments, and which have at all times been enjoyed by the citizens of the several states which compose this Union from the time of their becoming free, independent, and sovereign. What these fundamental principles are it would, perhaps, be more tedious than difficult to enumerate. They may, however, be all comprehended under the following heads: protection by the government, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety, subject nevertheless to such restraints as the government may justly prescribe for the general good of the whole. The right of a citizen of one state to pass through or to reside in any other state, for purposes of trade, agriculture, professional pursuits, or otherwise; to claim the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus; to institute and maintain actions of any kind in the courts of the state; to take, hold, and dispose of property, either real or personal, and an exemption from higher taxes or impositions than are paid by the other citizens of the state, may be mentioned as some of the particular privileges and immunities of citizens which are clearly embraced by the general description of privileges deemed to be fundamental, to which may be added the elective franchise, as regulated and established by the laws or constitution of the state in which it is to be exercised. These, and many others which might be mentioned, are, strictly speaking, privileges and immunities, and the enjoyment of them by the citizens of each state in every other state was manifestly calculated (to use the expressions of the preamble of the corresponding provision in the old Articles of Confederation) “the better to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different states of the Union.”

Such is the character of the privileges and immunities spoken of in the second section of the fourth article of the Constitution. To these privileges and immunities, whatever they may be—for they are not and cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature—to these should be added the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution; such as the freedom of speech and of the press; the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for a redress of grievances, a right appertaining to each and all the people; the right to keep and to bear arms; the right to be exempted from the quartering of soldiers in a house without the consent of the owner; the right to be exempt from unreasonable searches and seizures, and from any search or seizure except by virtue of a warrant issued upon a formal oath or affidavit; the right of an accused person to be informed of the nature of the accusation against him, and his right to be tried by an impartial jury of the vicinage; and also the right to be secure against excessive bail and against cruel and unusual punishments.

Now, sir, here is a mass of privileges, immunities, and rights, some of them secured by the second section of the fourth article of the Constitution, which I have recited, some by the first eight amendments of the Constitution; and it is a fact well worthy of attention that the course of decision of our courts and the present settled doctrine is that all these immunities, privileges, rights, thus guaranteed by the Constitution or recognized by it, are secured to the citizen solely as a citizen of the United States and as a party in their courts. They do not operate in the slightest degree as a restraint or prohibition upon state legislation. States are not affected by them, and it has been repeatedly held that the restriction contained in the Constitution against the taking of private property for public use without just compensation is not a restriction upon state legislation, but applies only to the legislation of Congress.

Now, sir, there is no power given in the Constitution to enforce and to carry out any of these guarantees. They are not powers granted by the Constitution to Congress, and of course do not come within the sweeping clause of the Constitution authorizing Congress to pass all laws necessary and proper for carrying out the foregoing or granted powers,2 but they stand simply as a bill of rights in the Constitution, without power on the part of Congress to give them full effect; while at the same time the states are not restrained from violating the principles embraced in them except by their own local constitutions, which may be altered from year to year. The great object of the first section of this amendment is, therefore, to restrain the power of the states and compel them at all times to respect these great fundamental guarantees. How will it be done under the present amendment? As I have remarked, they are not powers granted to Congress, and therefore it is necessary, if they are to be effectuated and enforced, as they assuredly ought to be, that additional power should be given to Congress to that end. This is done by the fifth section of this amendment, which declares that “the Congress shall have power to enforce by appropriate legislation the provisions of this article.” Here is a direct affirmative delegation of power to Congress to carry out all the principles of these guarantees, a power not found in the Constitution.

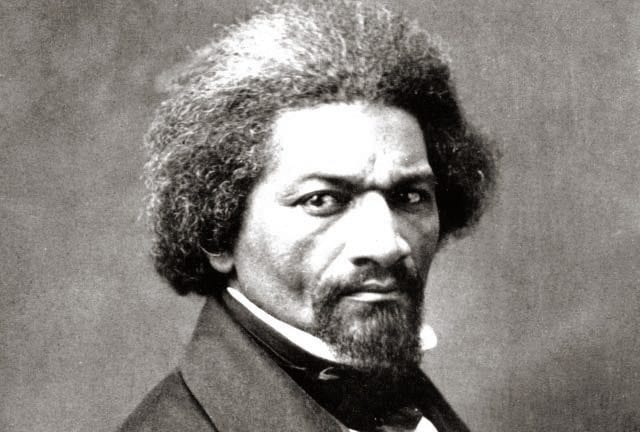

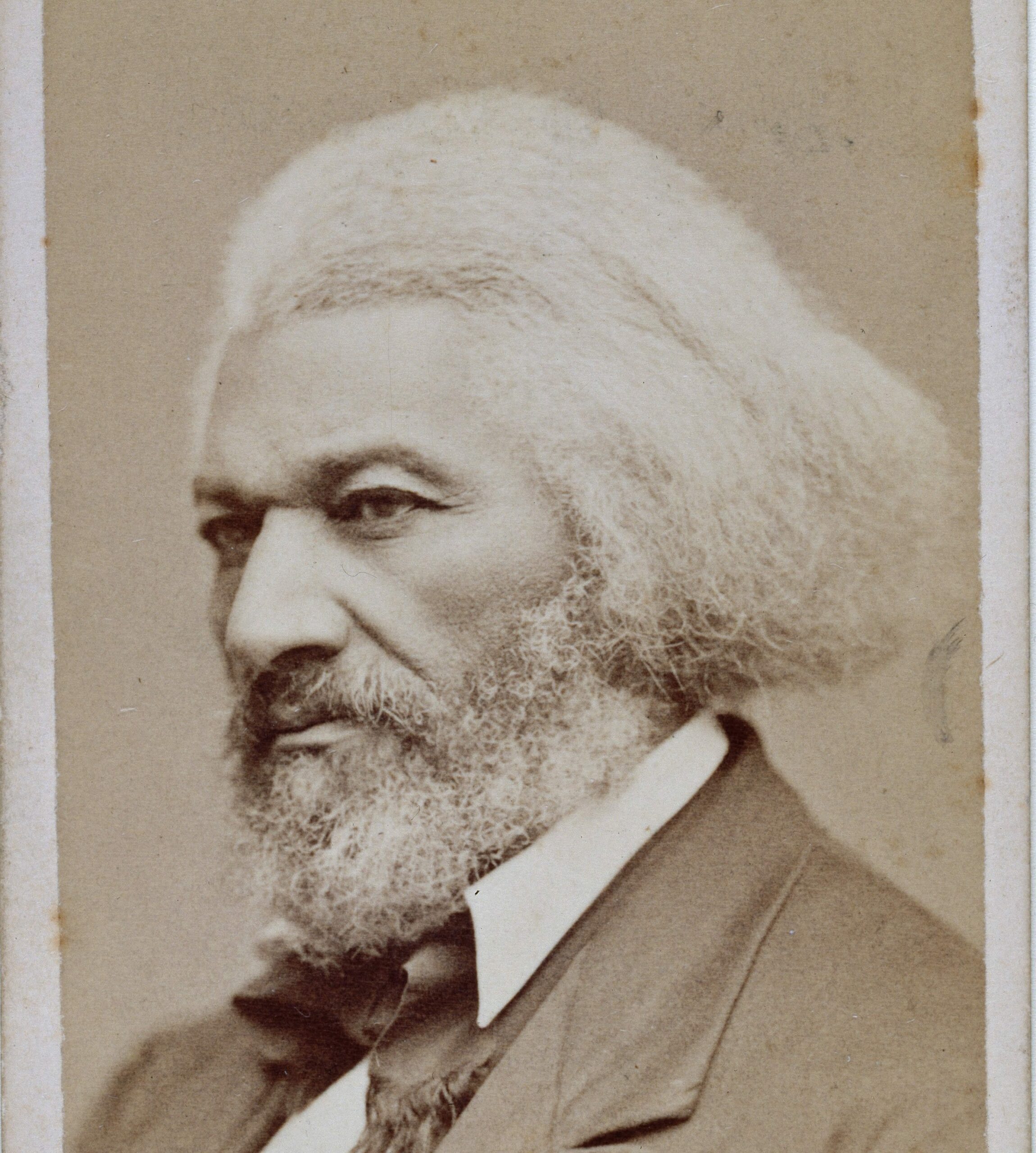

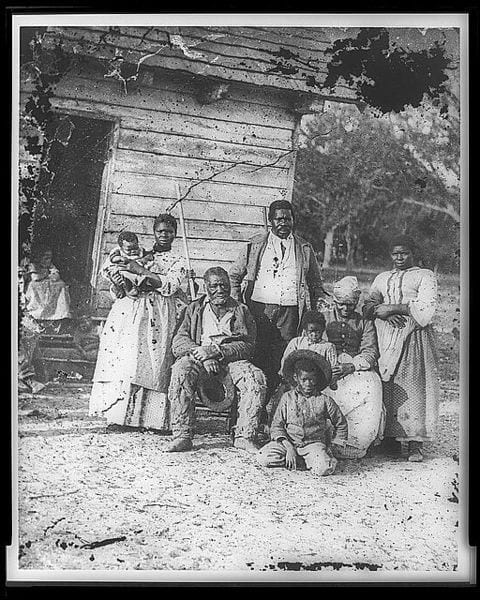

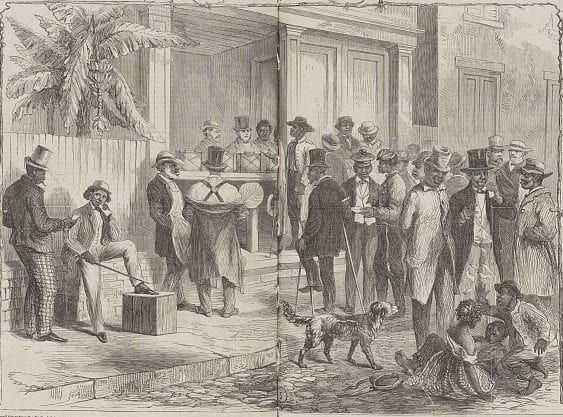

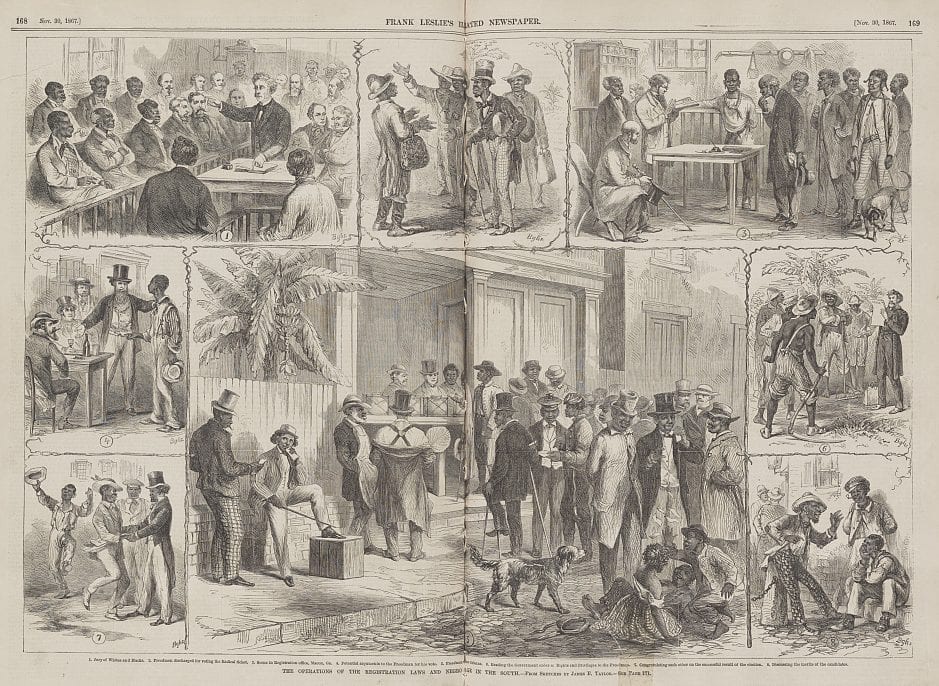

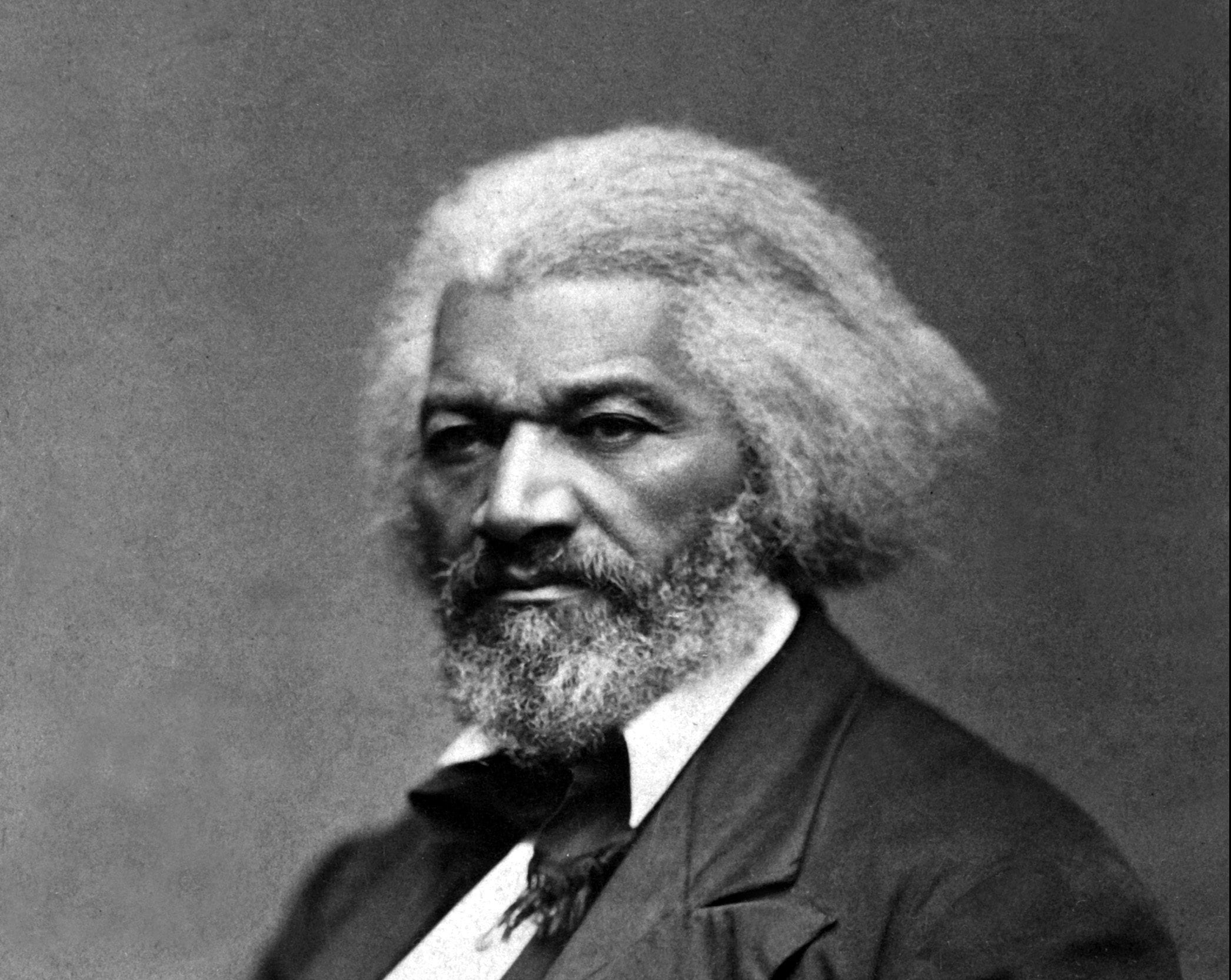

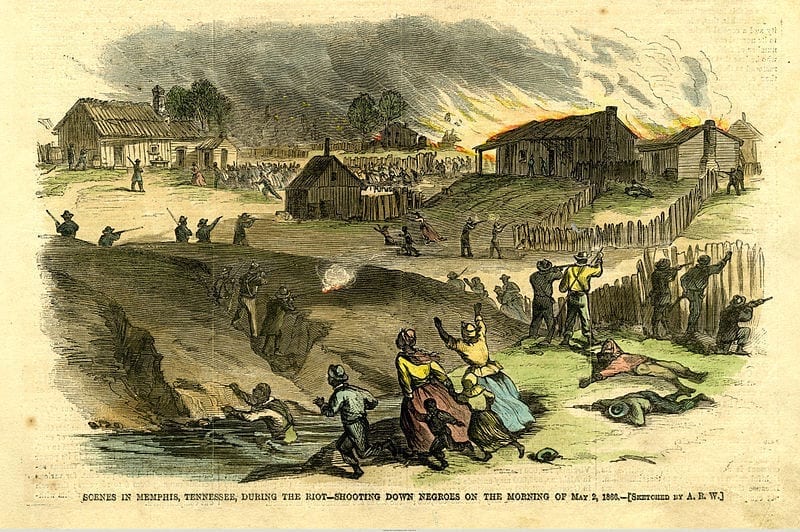

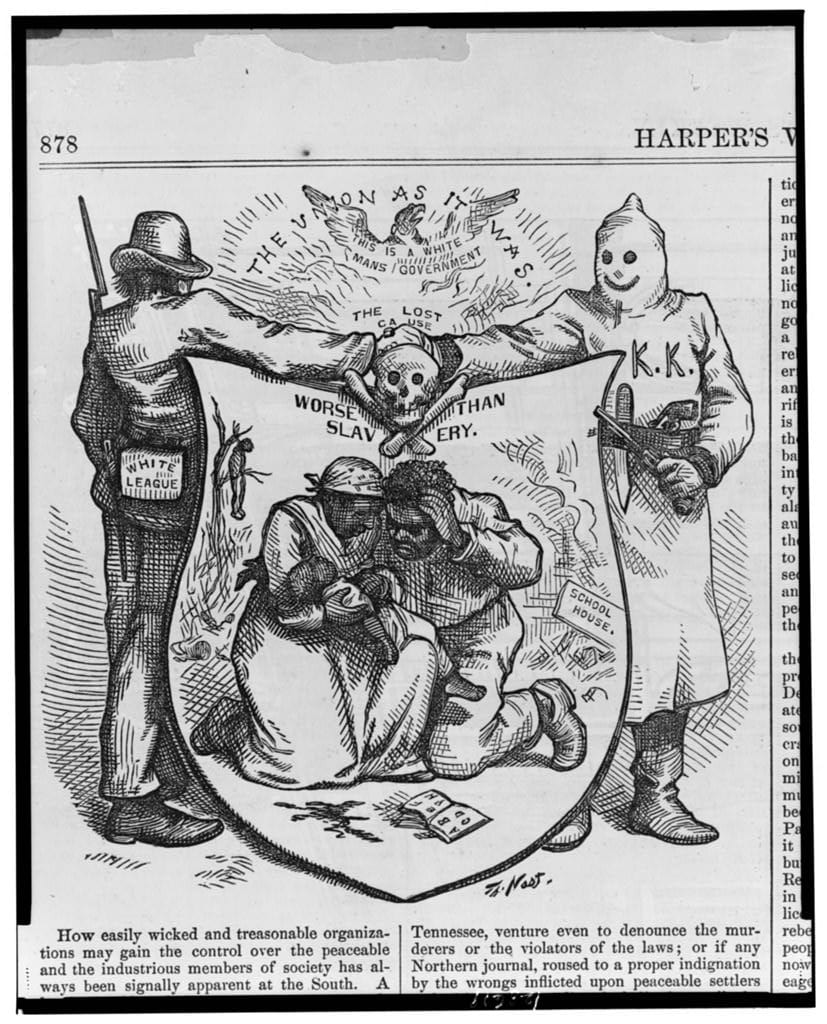

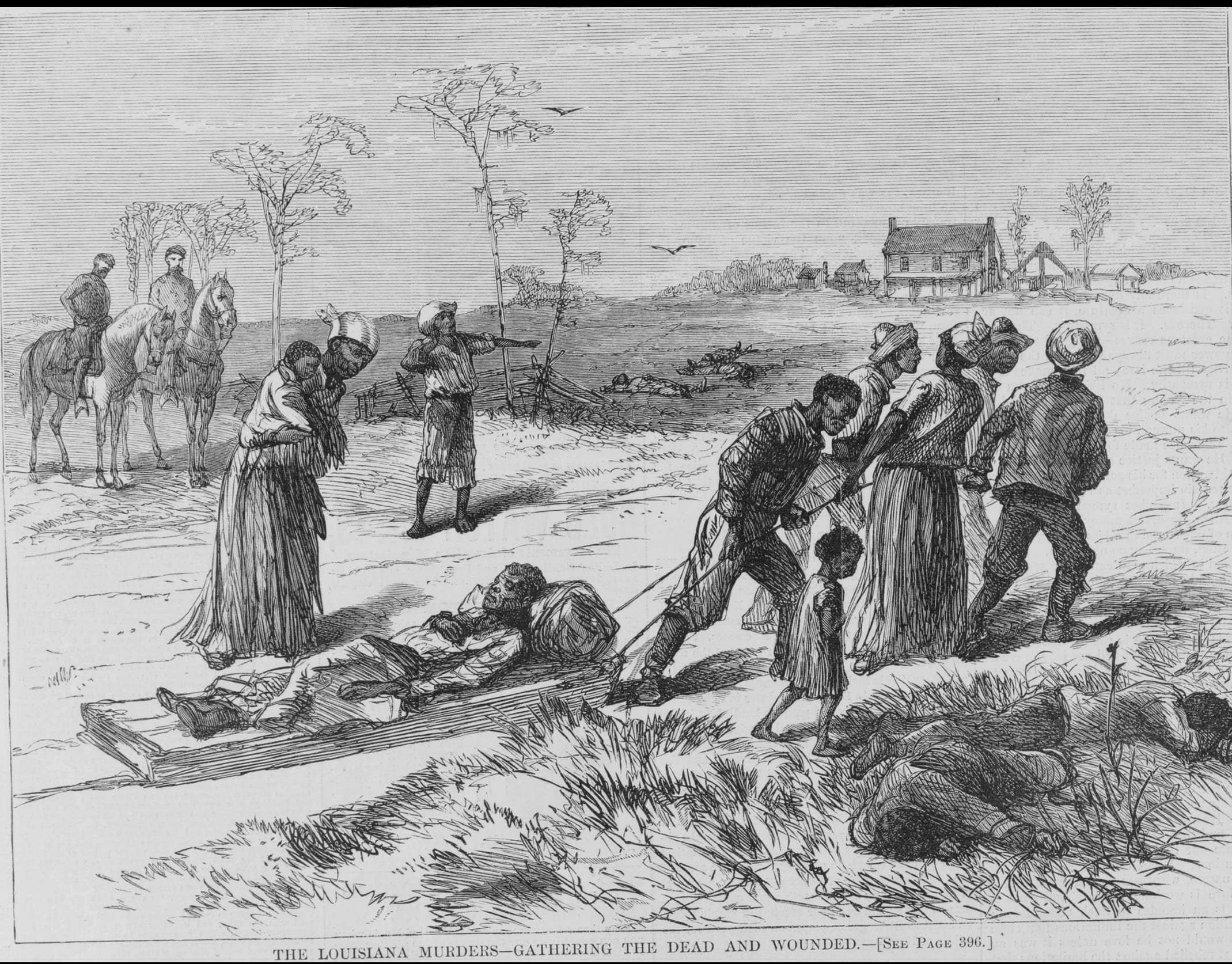

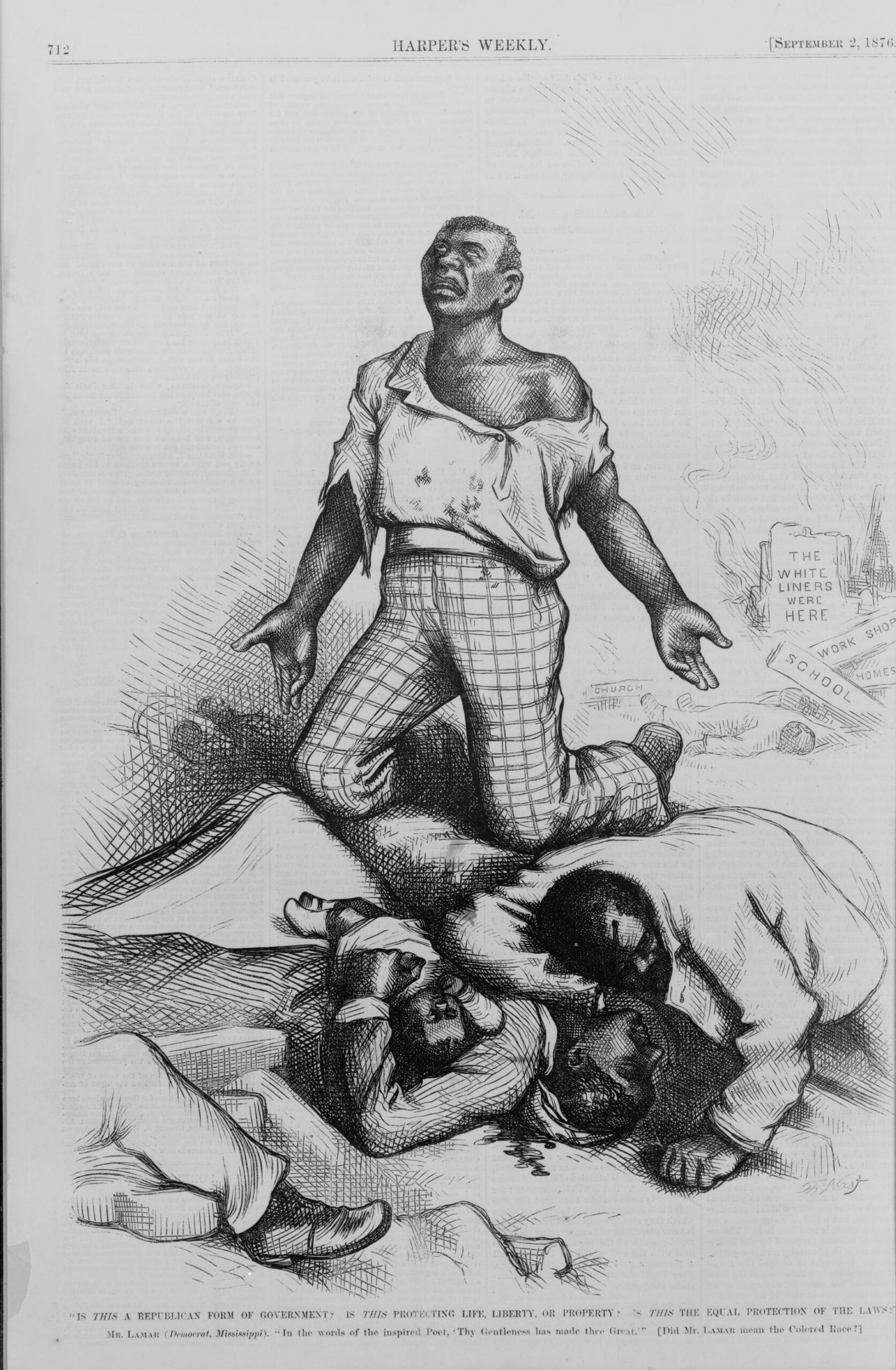

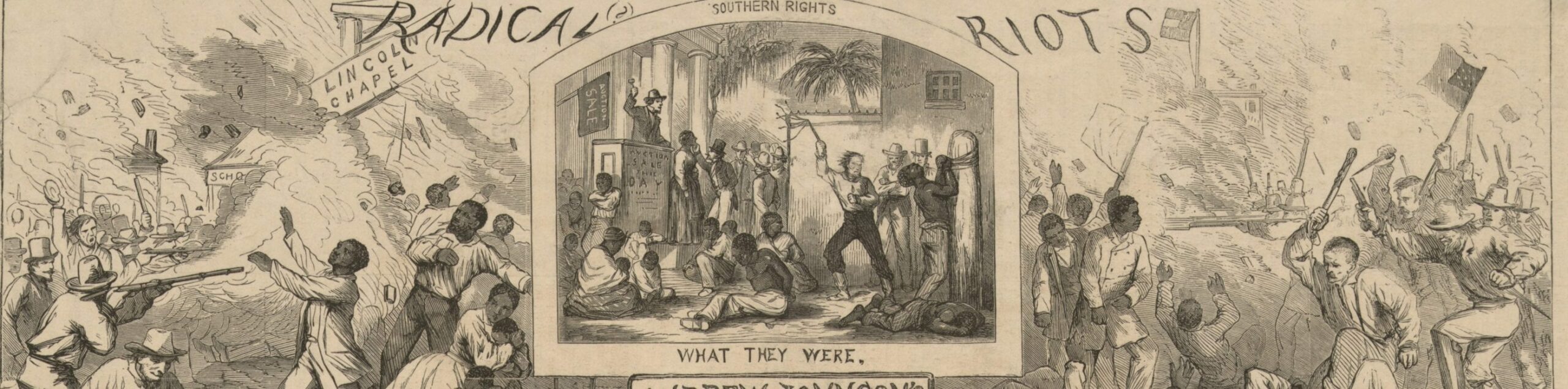

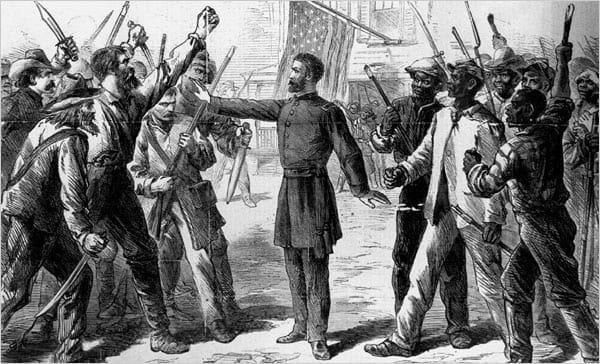

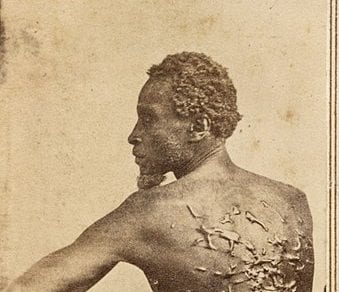

The last two clauses of the first section of the amendment disable a state from depriving not merely a citizen of the United States, but any person, whoever he may be, of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or from denying to him the equal protection of the laws of the state. This abolishes all class legislation in the states and does away with the injustice of subjecting one caste of persons to a code not applicable to another. It prohibits the hanging of a black man for a crime for which the white man is not to be hanged. It protects the black man in his fundamental rights as a citizen with the same shield which it throws over the white man. Is it not time, Mr. President, that we extend to the black man, I had almost called it the poor privilege of the equal protection of the law? Ought not the time to be now passed when one measure of justice is to be meted out to a member of one caste while another and different measure is meted out to the member of another caste, both castes being alike citizens of the United States, both bound to obey the same laws, to sustain the same burdens of the same government, and both equally responsible to justice and to God for the deeds done in the body?

But, sir, the first section of the proposed amendment does not give to either of these classes the right of voting. The right of suffrage is not, in law, one of the privileges or immunities thus secured by the Constitution. It is merely the creature of law. It has always been regarded in this country as the result of positive local law, not regarded as one of those fundamental rights lying at the basis of all society and without which a people cannot exist except as slaves, subject to a despotism.

As I have already remarked, section one is a restriction upon the states, and does not, of itself, confer any power upon Congress. The power which Congress has, under this amendment, is derived, not from that section, but from the fifth section, which gives it authority to pass laws which are appropriate to the attainment of the great object of the amendment. I look upon the first section, taken in connection with the fifth, as very important. It will, if adopted by the states, forever disable every one of them from passing laws trenching upon those fundamental rights and privileges which pertain to citizens of the United States, and to all persons who may happen to be within their jurisdiction. It establishes equality before the law, and it gives to the humblest, the poorest, the most despised of the race the same rights and the same protection before the law as it gives to the most powerful, the most wealthy, or the most haughty. That sir is republican government, as I understand it, and the only one which can claim the praise of a just government. Without this principle of equal justice to all men and equal protection under the shield of the law, there is no republican government and none that is really worth maintaining....

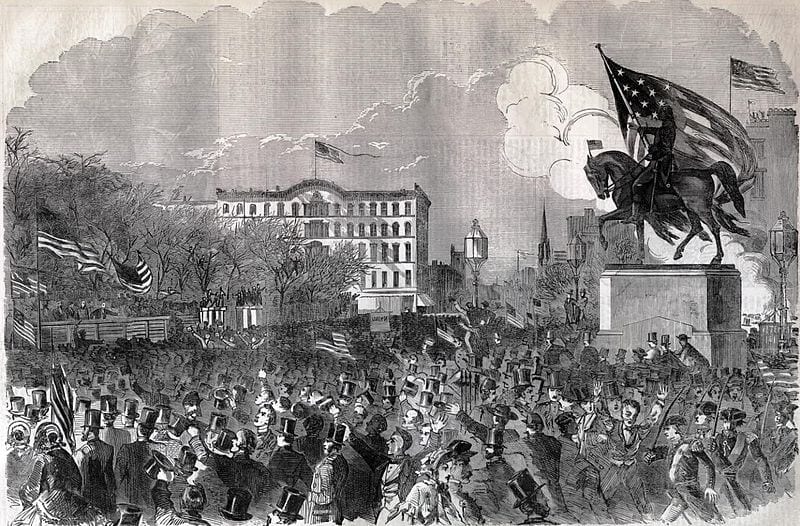

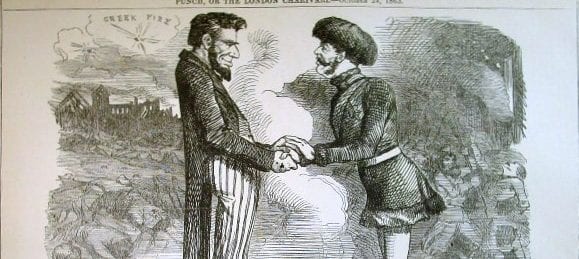

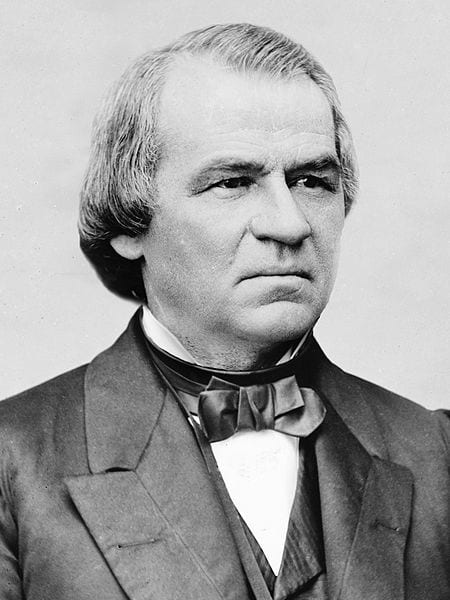

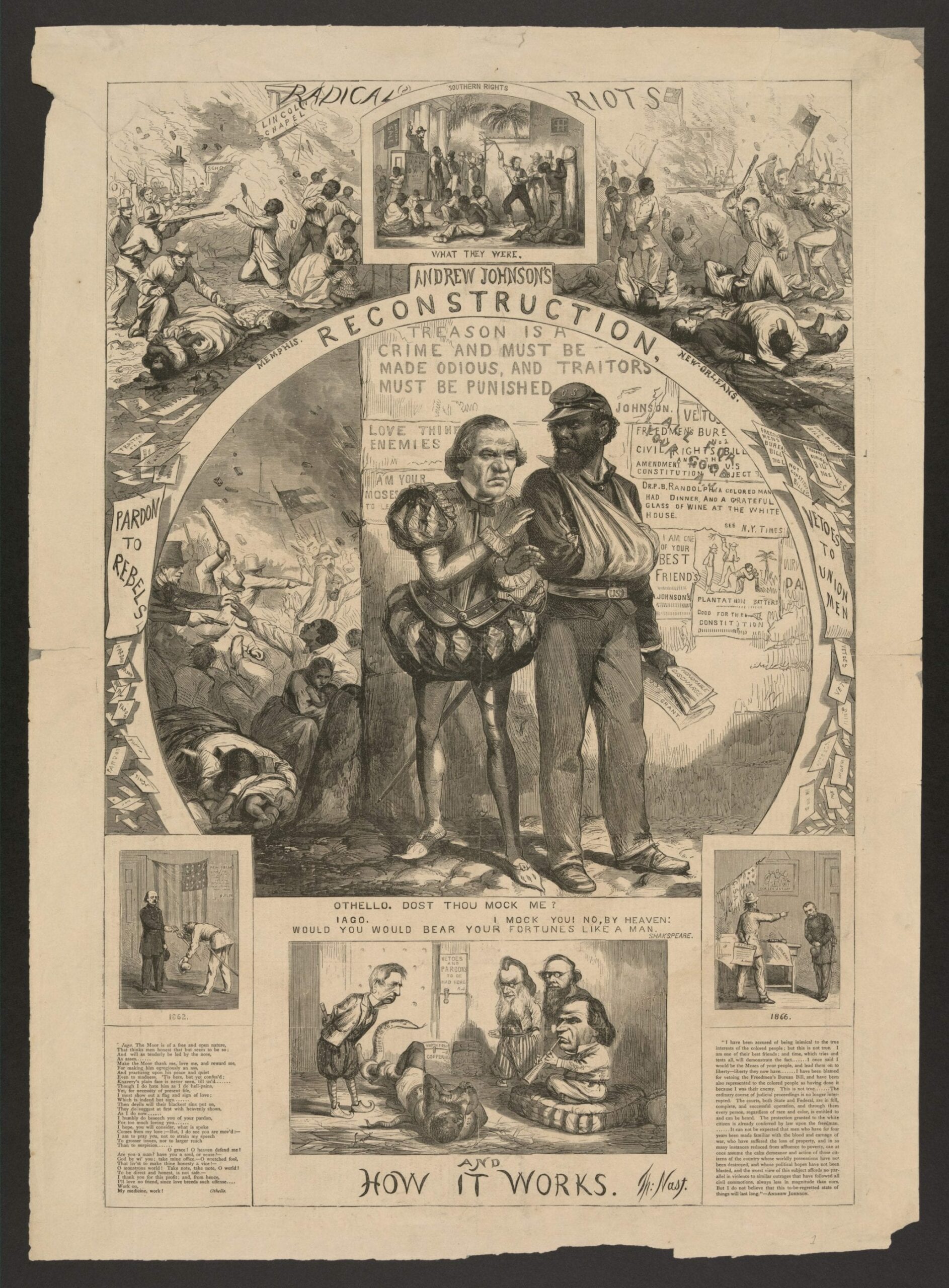

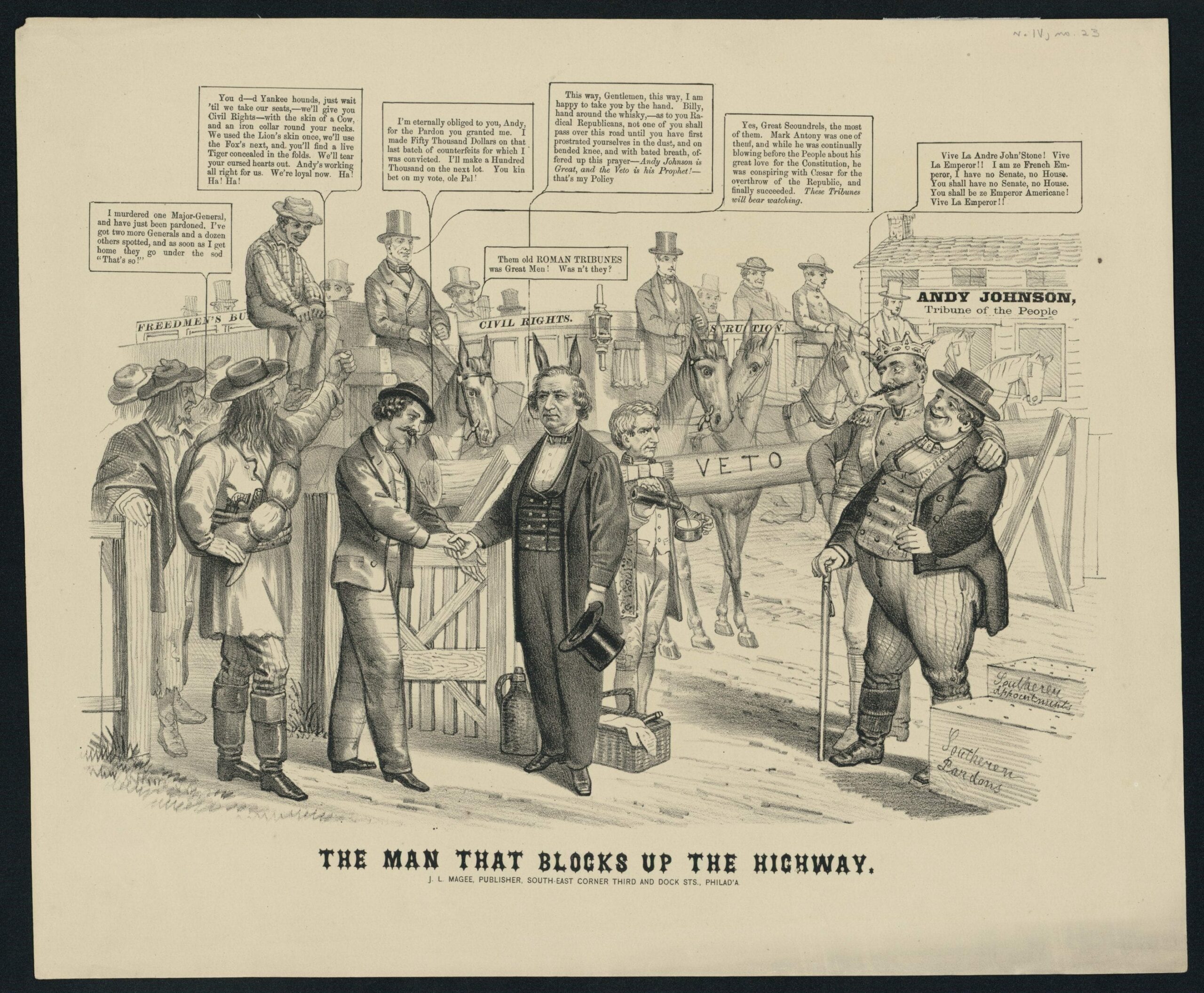

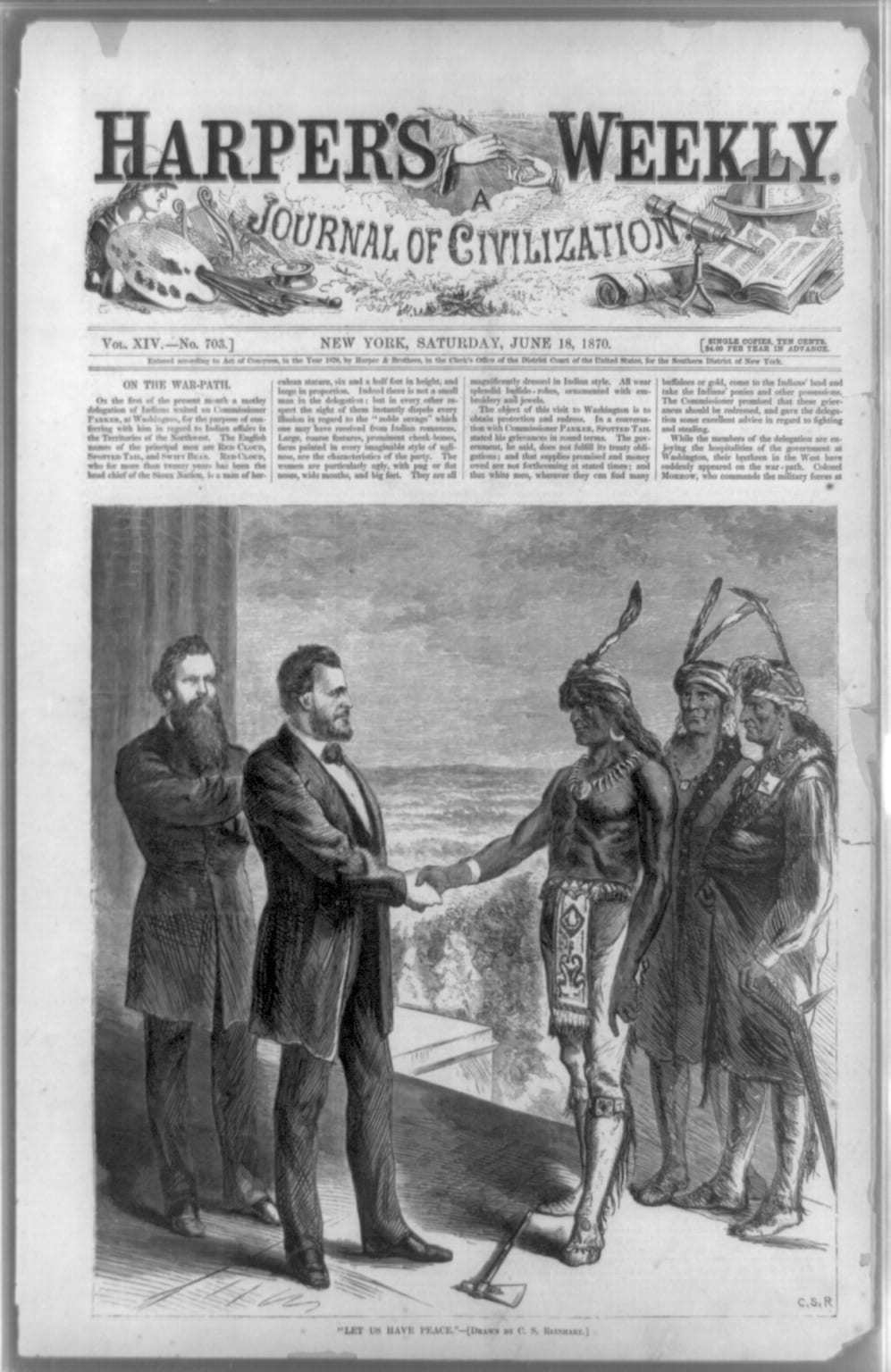

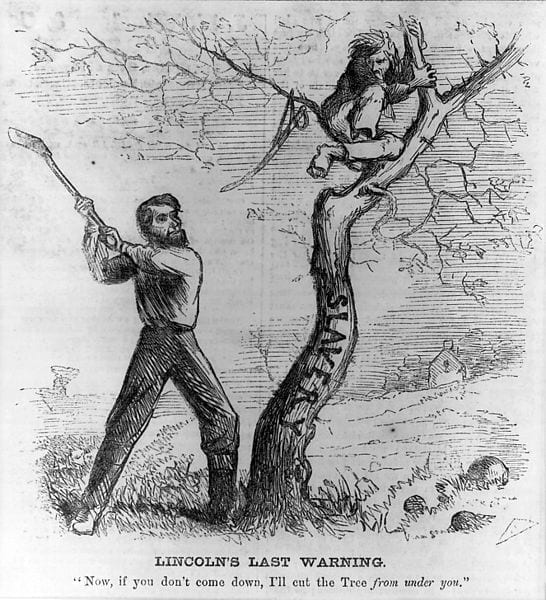

The One Man Power vs. Congress!

October 02, 1866

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.