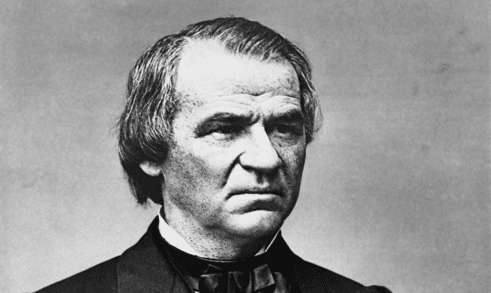

States determine who can vote, for the most part, under the original Constitution of the United States. According to Article 1, Section 2, whoever can vote for the “most numerous branch of state legislatures” could vote for members of the House of Representatives. States decide who is eligible for those most numerous branches. States could, if they chose, impose voting restrictions based on property, race, sex, age and other characteristics. Soon after the Civil War, it became a question whether or not states and especially Southern states would continue to have the freedom to restrict the vote. President Abraham Lincoln seemed to imply that he favored granting of the vote to blacks in his Last Public Address, but he stopped short of requiring such a provision in state constitutions. President Andrew Johnson opposed requiring that restored Southern governments give the vote to blacks.

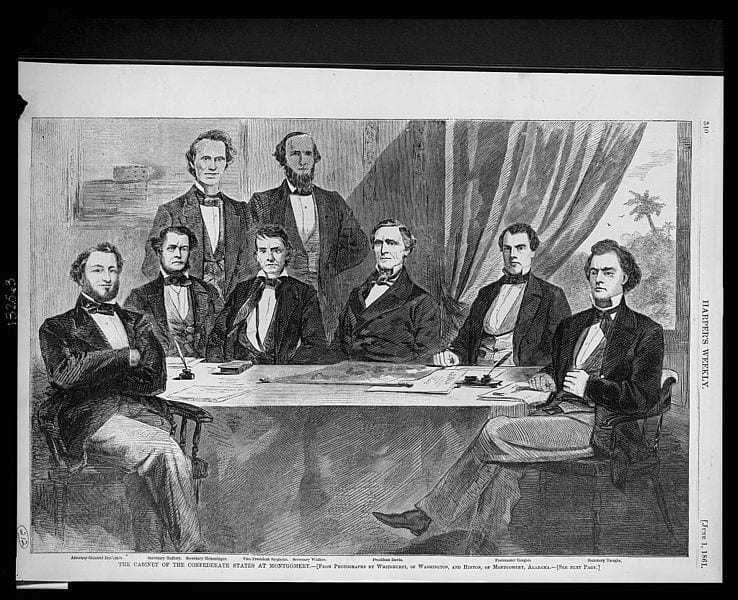

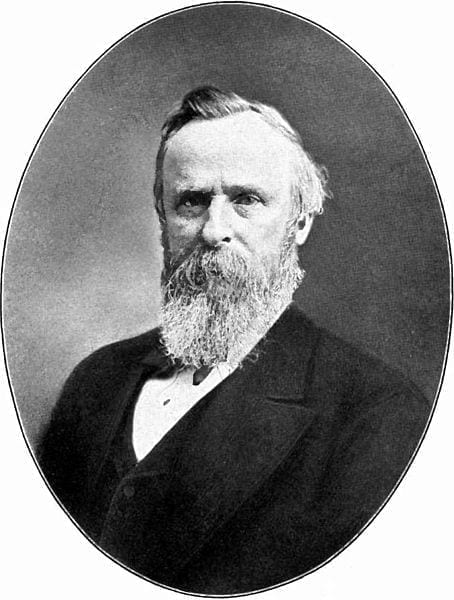

The Republican sweep of the 1866 election gave momentum to the idea of extending the vote. From early 1867, Representative Thaddeus Stevens (R-PA) favored extending the franchise to blacks and disenfranchising former rebels. Senator Charles Sumner favored much the same scheme. The invigorated Republican Congress took action where it could under the Constitution – in the nation’s capital and in the territories. In January 1867, a bill enfranchising blacks in the District of Columbia passed over Johnson’s veto. In short order, Congress extended the vote to all men in the territories. Military rule under the Reconstruction Acts was coming to an end in the South as President Grant took office in 1869. No longer would the military direct the politics of the South, and no longer would it provide protection for blacks. Republicans therefore approved the 15th amendment in February 1869, partly as a means to empower blacks to protect themselves with the vote.