Introduction

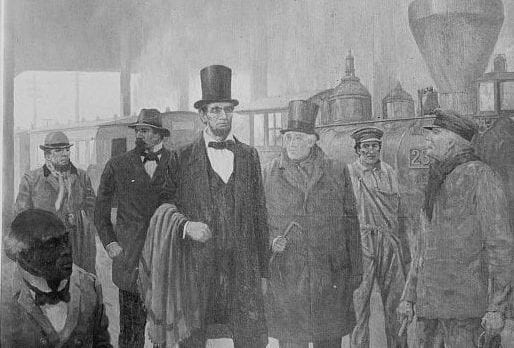

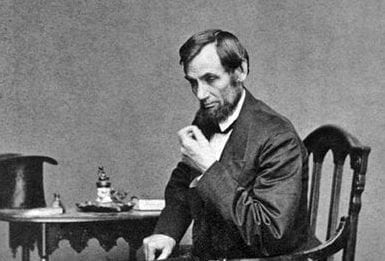

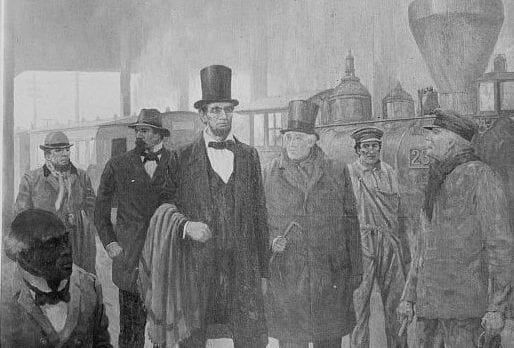

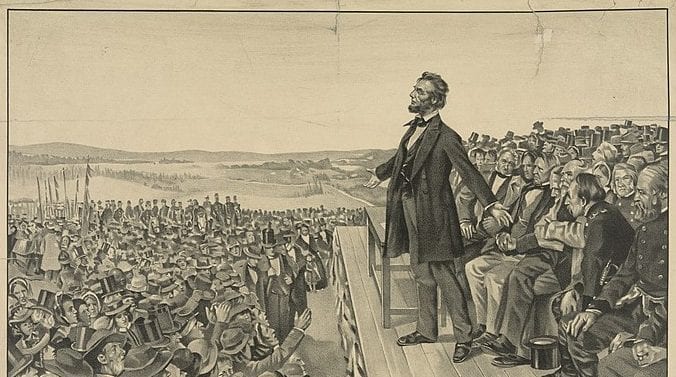

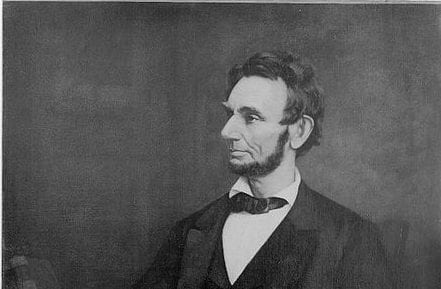

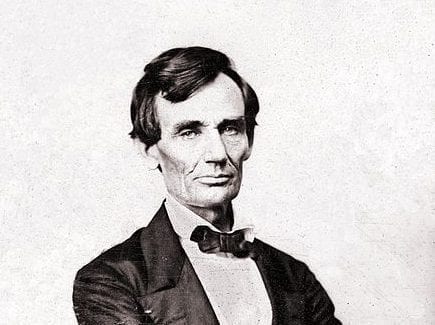

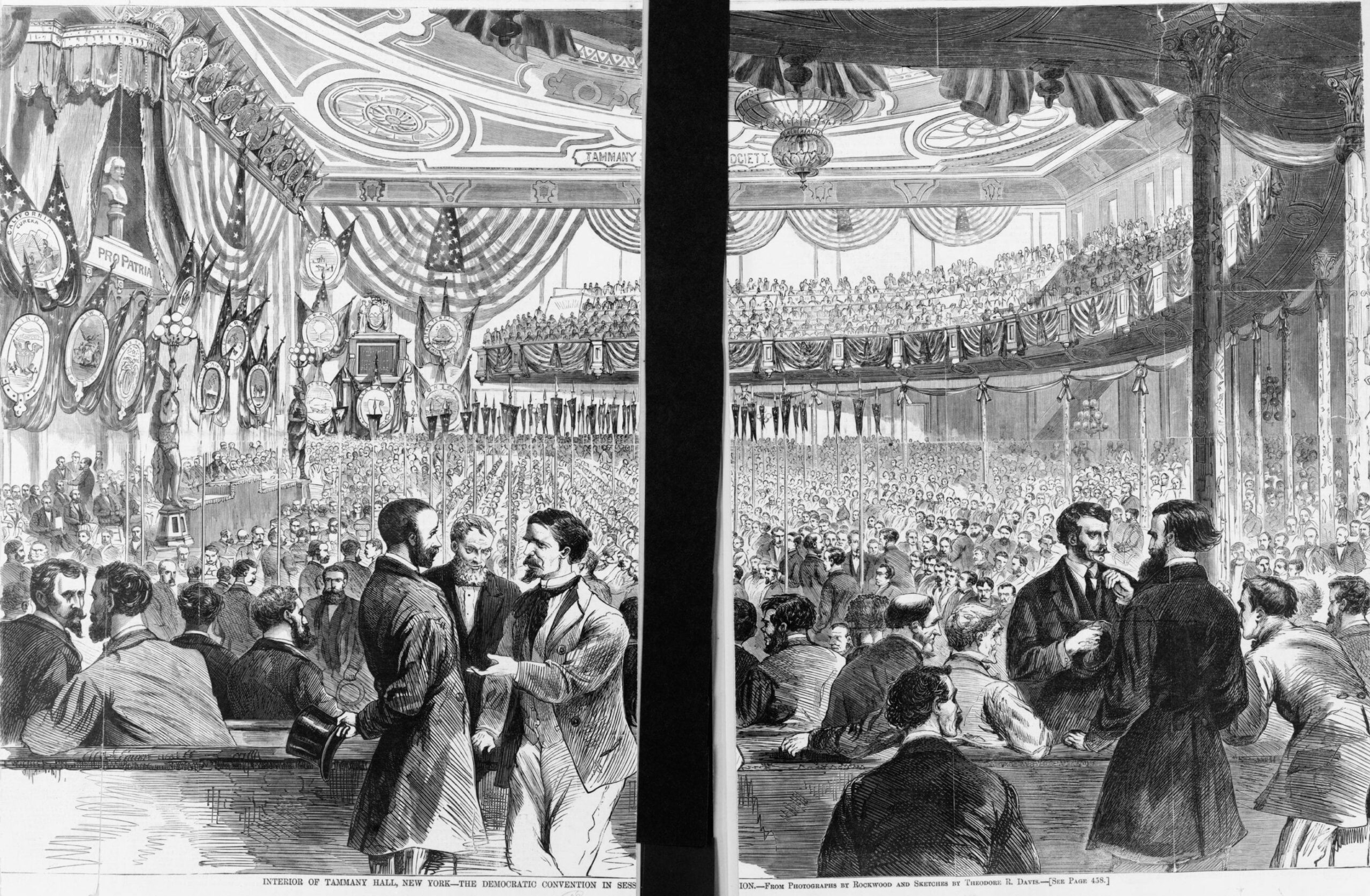

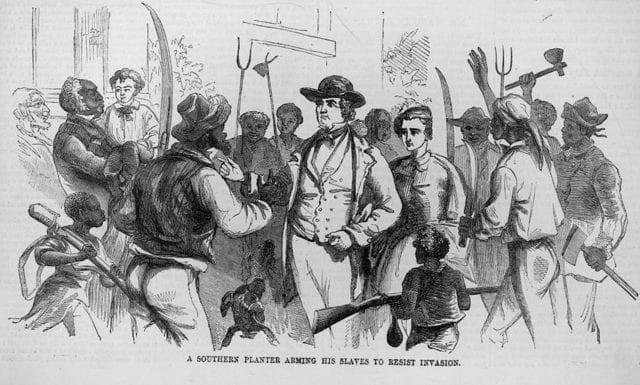

This impromptu speech was delivered at a flag-raising ceremony while President-elect Lincoln was on his way from his home in Springfield, Illinois, to his inauguration in Washington, DC, on March 4. Beginning with his farewell address to his state in Springfield on February 11, Lincoln made short speeches along his circuitous route. Washington’s Birthday found him in Philadelphia at Independence Hall, where both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were signed—the documents at the center of the ongoing struggle over slavery.

In his remarks in Philadelphia, Lincoln reaffirmed his fidelity to the Constitution and the Declaration as the moral basis of the Union and as the source of hope for humankind. In making these remarks, he departed from his policy of silence during the Secession Winter (the interval between his election and inauguration) (See Fragment on the Constitution and Union). He also referred to a report he had received of a plot to assassinate him in Baltimore, claiming that he would rather suffer death than surrender the core principle of equality. Finally, he assured his listeners of his determination to save the Union, but there would be no war unless it was forced upon the government.

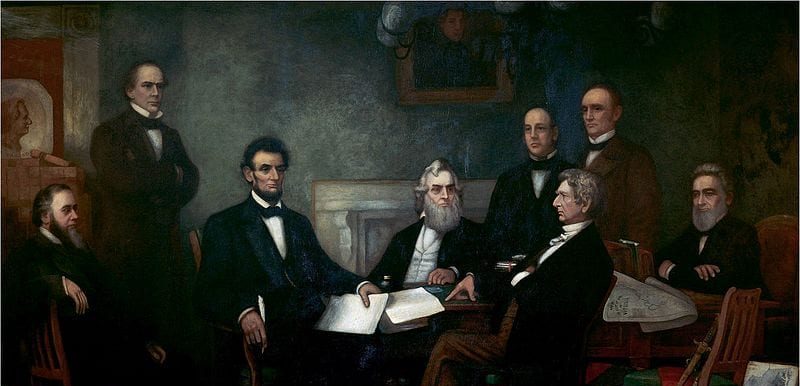

—Joseph R. Fornieri and David Tucker

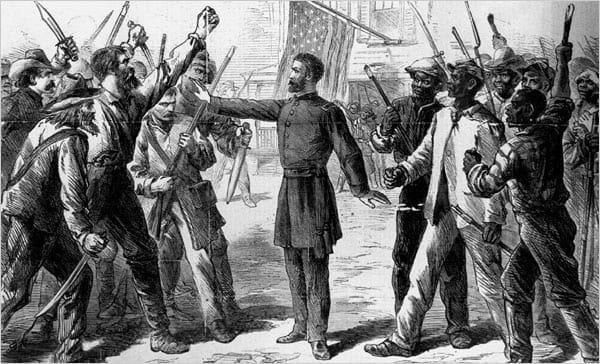

Mr. Cuyler:1 I am filled with deep emotion at finding myself standing here, in this place, where were collected together the wisdom, the patriotism, the devotion to principle, from which sprang the institutions under which we live. You have kindly suggested to me that in my hands is the task of restoring peace to the present distracted condition of the country. I can say in return, sir, that all the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated and were given to the world from this hall. I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence. I have often pondered over the dangers which were incurred by the men who assembled here and framed and adopted that Declaration of Independence. I have pondered over the toils that were endured by the officers and soldiers of the army who achieved that independence. I have often inquired of myself what great principle or idea it was that kept this confederacy so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the motherland; but that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country but, I hope, to the world, for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weight would be lifted from the shoulders of all men. This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence.

Now, my friends, can this country be saved upon that basis? If it can, I will consider myself one of the happiest men in the world if I can help to save it. If it can’t be saved upon that principle, it will be truly awful. But if this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle—I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender it. Now, in my view of the present aspect of affairs, there is no need of bloodshed and war. There is no necessity for it. I am not in favor of such a course, and I may say in advance, there will be no blood shed unless it be forced upon the government. The government will not use force unless force is used against it. My friends, this is a wholly unprepared speech. I did not expect to be called upon to say a word when I came here—I supposed I was merely to do something toward raising a flag. I may, therefore, have said something indiscreet, but I have said nothing but what I am willing to live by, and, in the pleasure of Almighty God, die by.