Introduction

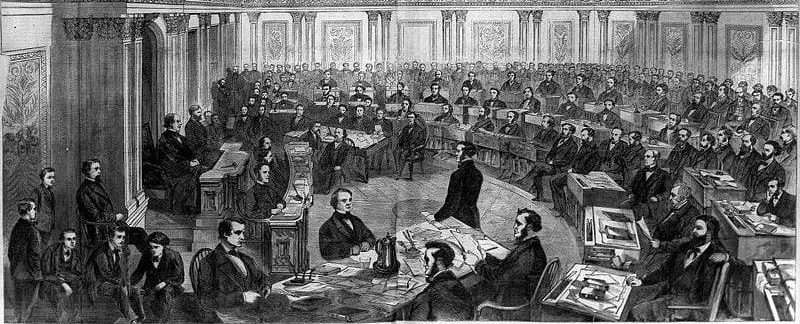

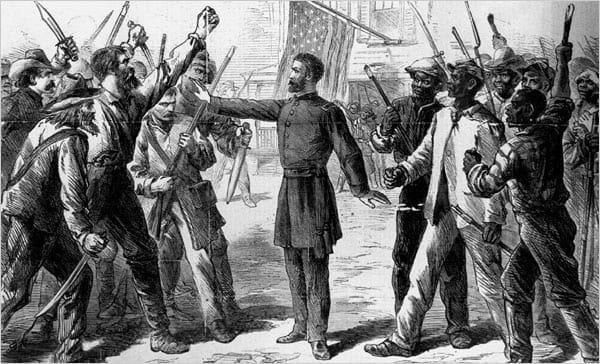

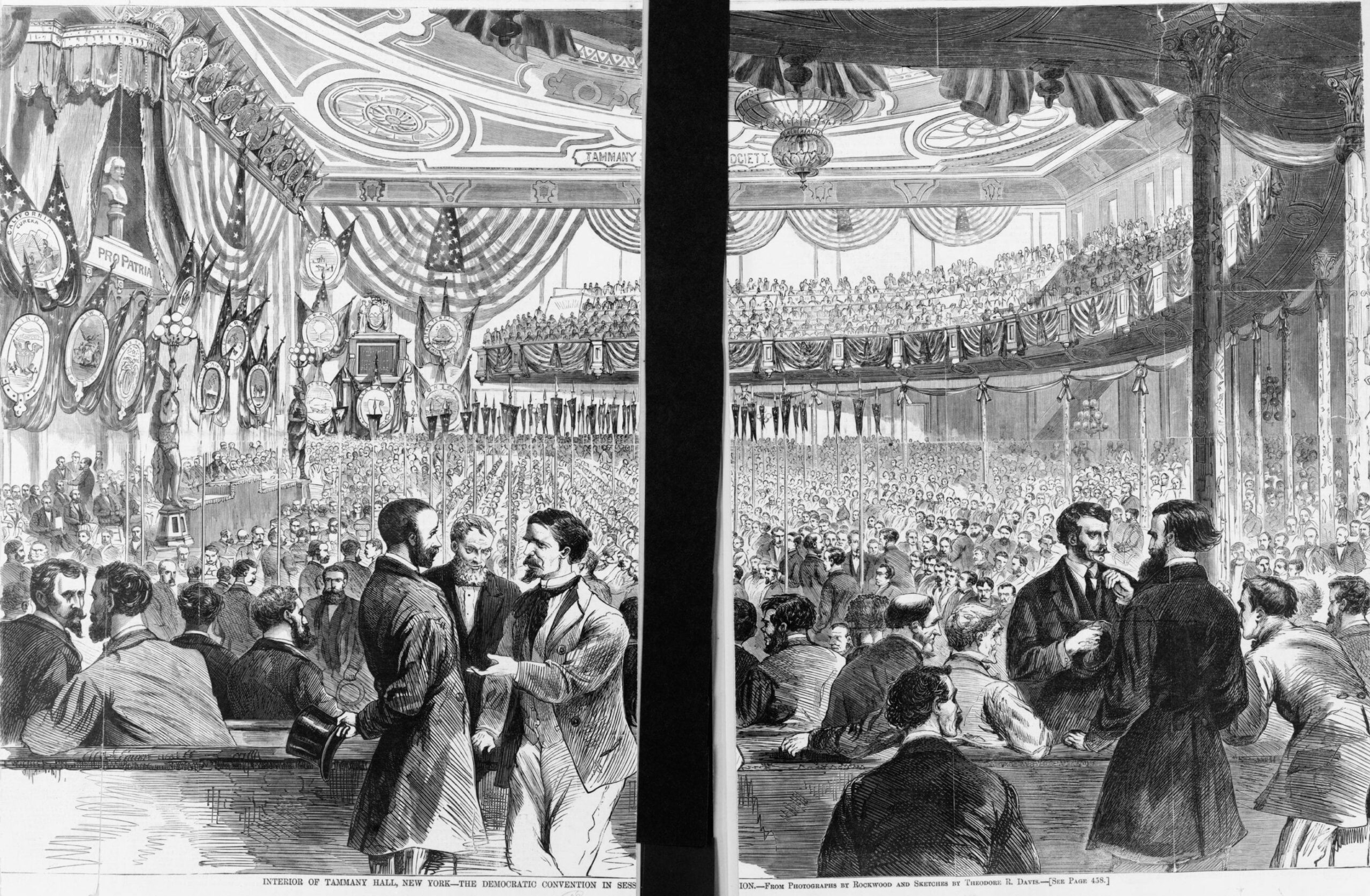

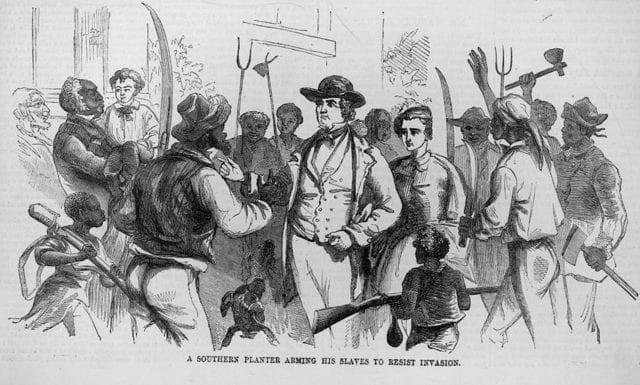

President Andrew Johnson, opposed to the comparatively mild intervention represented in the Freedman’s Bureau and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, took the unusual step of campaigning against the Republican Congress during the elections of 1866. He warned the country about the “Africanizing” tendencies of Republican policies and of the ways that, he believed, the Republicans were subverting the constitutional order. Nevertheless, Republicans swept to victory. Worried that their previous attempts at Reconstruction were not meeting with success, they now had veto-proof majorities with which to do something about it. The problems were manifold. First, Johnson opposed the Civil Rights Act and was lax in his administration of it. Second, riots and low-level rebellion cropped up in major southern cities such as Memphis and New Orleans, leaving dozens of freedmen dead or wounded. Third and most important, the “reconstructed” southern states refused to ratify the 14th Amendment or to act in ways generally consistent with its strictures. Voluntary or semi-voluntary reconstruction was not bettering the condition of freedmen, nor was it leading to a revival of Union sentiments. Republicans, invigorated by the electorate’s rejection of Johnson, started reconstruction all over again, in a sense, with the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867, passed on the last day of the 39th Congress, and its progeny, passed in the first days of the 40th Congress. These bills divided the South into five military districts, each under the supervision of a general who was charged with reconstructing the Southern constitutions to comport with the strictures of the 14th Amendments and with taking steps to allow blacks to vote. Even though the Reconstruction Acts passed Congress overwhelmingly, Johnson vetoed all of them; and Congress overrode all his vetoes. The selection below, representative of Johnson’s objections to all the Reconstruction Acts, comes from his veto of the first one.

Source: Andrew Johnson, “Veto Message,” March 2, 1867. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://goo.gl/LbX7C2.

I have examined the bill “to provide for the more efficient government of the rebel States” with the care and anxiety which its transcendent importance is calculated to awaken. I am unable to give it my assent for reasons so grave that I hope a statement of them may have some influence on the minds of the patriotic and enlightened men with whom the decision must ultimately rest.

The bill places all the people of the ten States therein named under the absolute domination of military rulers; and the preamble . . . declares that there exists in those States no legal governments and no adequate protection for life or property, and asserts the necessity of enforcing peace and good order within their limits. Is this true as matter of fact? . . .

The provisions which these governments have made for the preservation of order, the suppression of crime, and the redress of private injuries are in substance and principle the same as those which prevail in the Northern States and in other civilized countries. . . . All the information I have on the subject convinces me that the masses of the Southern people and those who control their public acts, while they entertain diverse opinions on questions of Federal policy, are completely united in the effort to reorganize their society on the basis of peace and to restore their mutual prosperity as rapidly and as completely as their circumstances will permit.

The bill, however, would seem to show upon its face that the establishment of peace and good order is not its real object. The fifth section declares that the preceding sections shall cease to operate in any State where certain events shall have happened. . . . All these conditions must be fulfilled before the people of any of these States can be relieved from . . . military domination; but when they are fulfilled, then immediately the pains and penalties of the bill are to cease, no matter whether there be peace and order or not, and without any reference to the security of life or property. . . . The military rule which it establishes is plainly to be used, not for any purpose of order or for the prevention of crime, but solely as a means of coercing the people into the adoption of principles and measures to which it is known that they are opposed, and upon which they have an undeniable right to exercise their own judgment.

I submit to Congress whether this measure is not in its whole character, scope, and object without precedent and without authority, in palpable conflict with the plainest provisions of the Constitution, and utterly destructive to those great principles of liberty and humanity for which our ancestors on both sides of the Atlantic have shed so much blood and expended so much treasure.

The ten States named in the bill are divided into five districts. For each district an officer of the Army . . . is to be appointed to rule over the people; and he is to be supported with an efficient military force to enable him to perform his duties and enforce his authority. Those duties and that authority, as defined by the third section of the bill, are “to protect all persons in their rights of person and property, to suppress insurrection, disorder, and violence, and to punish or cause to be punished all disturbers of the public peace or criminals.” The power thus given to the commanding officer over all the people of each district is that of an absolute monarch. His mere will is to take the place of all law. . . . He alone is permitted to determine what are rights of person or property, and he may protect them in such way as in his discretion may seem proper. It places at his free disposal all the lands and goods in his district, and he may distribute them . . . to whom he pleases. . . .

I come now to a question which is, if possible, still more important. Have we the power to establish and carry into execution a measure like this? I answer, Certainly not, if we derive our authority from the Constitution and if we are bound by the limitations which it imposes.

This proposition is perfectly clear, that no branch of the Federal Government – executive, legislative, or judicial – can have any just powers except those which it derives through and exercises under the organic law1 of the Union. Outside of the Constitution we have no legal authority more than private citizens, and within it we have only so much as that instrument gives us. This broad principle limits all our functions and applies to all subjects. It protects not only the citizens of States which are within the Union, but it shields every human being who comes or is brought under our jurisdiction. We have no right to do in one place more than in another that which the Constitution says we shall not do at all. If, therefore, the Southern States were in truth out of the Union, we could not treat their people in a way which the fundamental law forbids.

Some persons assume that the success of our arms in crushing the opposition which was made in some of the States to the execution of the Federal laws reduced those States and all their people, the innocent as well as the guilty, to the condition of vassalage and gave us a power over them which the Constitution does not bestow or define or limit. No fallacy can be more transparent than this. Our victories subjected the insurgents to legal obedience, not to the yoke of an arbitrary despotism. . . .

Invasion, insurrection, rebellion, and domestic violence were anticipated when the Government was framed, and the means of repelling and suppressing them were wisely provided for in the Constitution; but it was not thought necessary to declare that the States in which they might occur should be expelled from the Union. Rebellions . . . occurred prior to that out of which these questions grow; but the States continued to exist and the Union remained unbroken. . . .

I need not say to the representatives of the American people that their Constitution forbids the exercise of judicial power in any way but one – that is, by the ordained and established courts. It is equally well known that in all criminal cases a trial by jury is made indispensable by the express words of that instrument. . . . To what extent a violation of it might be excused in time of war or public danger may admit of discussion, but we are providing now for a time of profound peace, when there is not an armed soldier within our borders except those who are in the service of the Government. It is in such a condition of things that an act of Congress is proposed which, if carried out, would deny a trial by the lawful courts and juries to 9,000,000 American citizens and to their posterity for an indefinite period. It seems to be scarcely possible that anyone should seriously believe this consistent with a Constitution which declares in simple, plain, and unambiguous language that all persons shall have that right and that no person shall ever in any case be deprived of it. . . .

The United States are bound to guarantee to each State a republican form of government.2 Can it be pretended that this obligation is not palpably broken if we carry out a measure like this, which wipes away every vestige of republican government in ten States and puts the life, property, liberty, and honor of all the people in each of them under the domination of a single person clothed with unlimited authority? . . .

The purpose and object of the bill – the general intent which pervades it from beginning to end – is to change the entire structure and character of the State governments and to compel them by force to the adoption of organic laws and regulations which they are unwilling to accept if left to themselves. The Negroes have not asked for the privilege of voting; the vast majority of them have no idea what it means. This bill not only thrusts it into their hands, but compels them, as well as the whites, to use it in a particular way. If they do not form a constitution with prescribed articles in it and afterwards elect a legislature which will act upon certain measures in a prescribed way, neither blacks nor whites can be relieved from the slavery which the bill imposes upon them.

Without pausing here to consider the policy or impolicy [sic] of Africanizing the southern part of our territory, I would simply ask the attention of Congress to that manifest, well-known, and universally acknowledged rule of constitutional law which declares that the Federal Government has no jurisdiction, authority, or power to regulate such subjects for any State. To force the right of suffrage out of the hands of the white people and into the hands of the Negroes is an arbitrary violation of this principle. . . .

That the measure proposed by this bill does violate the Constitution in the particulars mentioned and in many other ways which I forbear to enumerate is too clear to admit of the least doubt. . . .

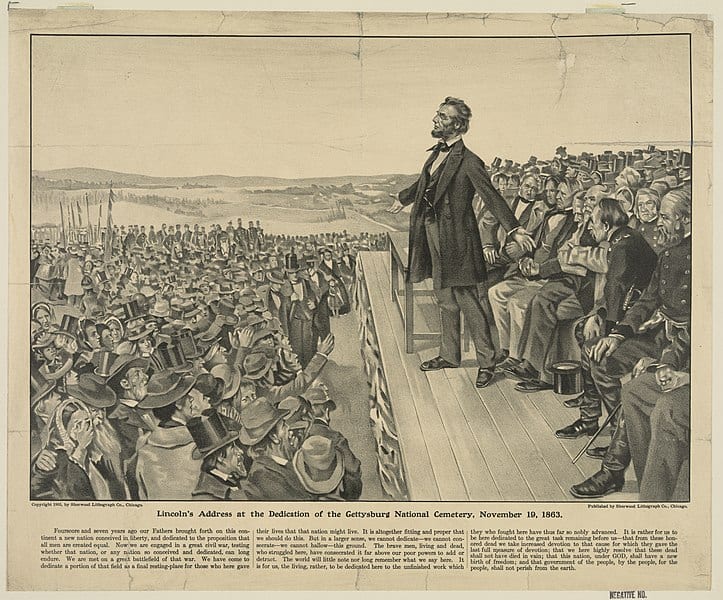

It is a part of our public history which can never be forgotten that both Houses of Congress, in July, 1861, declared in the form of a solemn resolution that the war was and should be carried on for no purpose of subjugation, but solely to enforce the Constitution and laws, and that when this was yielded by the parties in rebellion the contest should cease, with the constitutional rights of the States and of individuals unimpaired.3 This resolution was adopted and sent forth to the world unanimously by the Senate and with only two dissenting voices in the House. It was accepted by the friends of the Union in the South as well as in the North as expressing honestly and truly the object of the war. On the faith of it many thousands of persons in both sections gave their lives and their fortunes to the cause. To repudiate it now by refusing to the States and to the individuals within them the rights which the Constitution and laws of the Union would secure to them is a breach of our plighted honor for which I can imagine no excuse and to which I cannot voluntarily become a party. . . .

- 1. the fundamental system of laws or principles that defines the way a nation is governed

- 2. U.S. Constitution, Article IV, section 4.

- 3. Johnson refers to the Crittenden-Johnson or War Aims Resolution, of which he was one of the sponsors. He does not mention that the Resolution was repealed in December 1861, as public opinion in the North turned against the South.

Damages to Loyal Men

March 19, 1867

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.