No study questions

No related resources

SIR: Your confidential despatch of September 7, No. 342, has been received and carefully considered….

It is well understood that, through a long period, closing in 1860, the manifest strength of this nation was a sufficient protection, for itself and for Mexico, against all foreign states. That power was broken down and shattered in 1861, by faction. The first fruit of our civil war was a new, and in effect, though not intentionally so, an unfriendly attitude assumed by Great Britain, France, and Spain, all virtually, and the two first named powers avowedly, moving in concert. While I cannot confess to a fear on the part of this government that any one or all of the maritime powers combining with the insurgents could overthrow it, yet it would have been manifestly presumptuous, at any time since this distraction seized the American people, to have provoked such an intervention, or to have spared any allowable means of preventing it. The unceasing efforts of this department in that direction have resulted from this ever-present consideration. If in its communications the majestic efforts of the government to subdue the insurrection, and to remove the temptation which it offered to foreign powers, have not figured so largely as to impress my correspondents with the conviction that the President relies always mainly on the national power, and not on the forbearance of those who it is apprehended may become its enemies, it is because the duty of drawing forth and directing the armed power of the nation has rested upon distinct departments, while to this one belonged the especial duty of holding watch against foreign insult, intrusion, and intervention. With these general remarks I proceed to explain the President’s views in regard to the first of the two

questions mentioned, namely, the attitude of France in regard to the civil war in the United States.

We know from many sources, and even from the Emperor’s direct statement, that, on the breaking out of the insurrection, he adopted the current opinion of European statesmen that the efforts of this government to maintain and preserve the Union would be unsuccessful. To this prejudgment we attribute his agreement with Great Britain to act in concert with her upon the questions which might arise out of the insurrection; his concession of a belligerent character to the insurgents; his repeated suggestions of accommodation by this government with the insurgents; and his conferences on the subject of a recognition. It would be disingenuous to withhold an expression of the national conviction that these proceedings of the Emperor have been very injurious to the United States, by encouraging and thus prolonging the insurrection.

On the other hand, no statesman of this country is able to conceive of a reasonable motive, on the part of either France or the Emperor, to do or to wish injury to the United States. Every statesman of the United States cherishes a lively interest in the welfare and greatness of France, and is content that she shall enjoy peacefully and in unbounded prosperity the administration of the Emperor she has chosen. We have not an acre of territory or a port which we think France can wisely covet; nor has she any possession that we could accept if she would resign it into our hands. Nevertheless, when recurring to what the Emperor has already done, we cannot, at any time, feel assured that, under mistaken impressions of our exposure, he might not commit himself still further in the way of encouragement and aid to the insurgents. We know their intrigues in Paris are not to be lightly regarded. While the Emperor has held an unfavorable opinion of our national strength and unity, we, on the contrary, have as constantly indulged entire confidence in both.

Not merely the course of events, but that of time, also, runs against the insurgents and reinvigorates the national strength and power. We desire, therefore, that he may have the means of understanding the actual condition of affairs in our country. We wish to avoid anything calculated to irritate France, or to wound the just pride and proper sensibilities of that spirited nation, and thus to free our claim to her forbearance, in our present political emergency, from any cloud of passion or prejudice. Pursuing this course, the President hopes that the prejudgment of the Emperor against the stability of the Union may the sooner give way to convictions which will modify his course, and bring him back again to the traditional friendship which he found existing between this country and his own, when, in obedience to her voice, he assumed the reins of empire. These desires and purposes do not imply either a fear of French hostility, or any neglect of a prudent posture of national self-reliance.

The subject upon which I propose to remark, in the second place, is the relation of France towards Mexico. The United States hold, in regard to Mexico, the same principles that they hold in regard to all other nations. They have neither a right nor a disposition to intervene by force in the internal affairs of Mexico, whether to establish and maintain a republic or even a domestic government there, or to overthrow an imperial or a foreign one, if Mexico chooses to establish or accept it. The United States have neither the right nor the disposition to intervene by force on either side in the lamentable war which is going on between France and Mexico. On the contrary, they practice in regard to Mexico, in every phase of that war, the non-intervention which they require all foreign powers to observe in regard to the United States. But notwithstanding this self-restraint, this government knows full well that the inherent normal opinion of Mexico favors a government there republican in form and domestic in its organization, in preference to any monarchical institutions to be imposed from abroad. This government knows, also, that this normal opinion of the people of Mexico resulted largely from the, influence of popular opinion in this country, and is continually invigorated by it.

The President believes, moreover, that this popular opinion of the United States is just in itself, and eminently essential to the progress of civilization on the American continent, which civilization, it believes, can and will, if left free from European resistance, work harmoniously together with advancing refinement on the other continents. This government believes that foreign resistance, or attempts to control American civilization, must and will fail before the ceaseless and ever-increasing activity of material, moral, and political forces, which peculiarly belong to the American continent.

Nor do the United States deny that, in their opinion, their own safety and the cheerful destiny to which they aspire are intimately dependent on the continuance of free republican institutions throughout America. They have submitted these opinions to the Emperor of France, on proper occasions, as worthy of his serious consideration, in determining how he would conduct and close what might prove a successful war in Mexico. Nor is it necessary to practice reserve upon the point, that if France should, upon due consideration, determine to adopt a policy in Mexico adverse to the American opinions and sentiments which I have described, that policy would probably scatter seeds which would be fruitful of jealousies, which might ultimately ripen into collision between France and the United States and other American republics. An illustration of this danger has occurred already. Political rumor, which is always mischievous, one day ascribes to France a purpose to seize the Rio Grande, and wrest Texas from the United States; another day rumor advises us to look carefully to our safety on the Mississippi; another day we are warned of coalitions to be formed, under French patronage, between the regency established in Mexico and the insurgent cabal at Richmond. The President apprehends none of these things. He does not allow himself to be disturbed by suspicions so unjust to France and so unjustifiable in themselves; but he knows, also, that such suspicions will be entertained more or less extensively by this country, and magnified in other countries equally unfriendly to France and to America; and he knows, also, that it is out of such suspicions that the fatal web of national animosity is most frequently woven. He believes that the Emperor of France must experience desires as earnest as our own for the preservation of that friendship between the two nations which is so full of guarantees of their common prosperity and safety.

Thinking this, the President would be wanting in fidelity to France, as well as to our own country, if he did not converse with the Emperor with entire sincerity and friendship upon the attitude which France is to assume in regard to Mexico. The statements made to you by M. Drouyn de l’Huys, concerning the Emperor’s intentions, are entirely satisfactory, if we are permitted to assume them as having been authorized to be made by the Emperor in view of the present condition of affairs in Mexico. It is true, as I have before remarked, that the Emperor’s purposes may hereafter change with changing circumstances. We, ourselves, however, are not unobservant of the progress of events at home and abroad; and in no case are we likely to neglect such provision for our own safety as every sovereign state must always be prepared to fall back upon when nations with which they have lived in friendship cease to respect their moral and treaty obligations. Your own discretion will be your guide as to how far and in what way the public interests will be promoted, by submitting these views to the consideration of M. Drouyn de l’Huys.

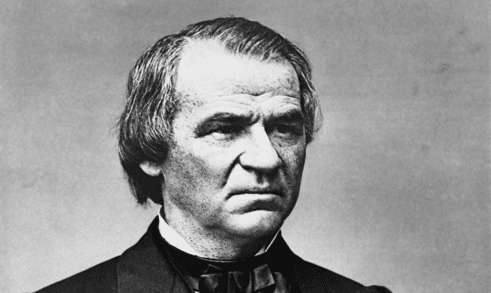

I am, sir, your obedient servant,

WILLIAM H. SEWARD.

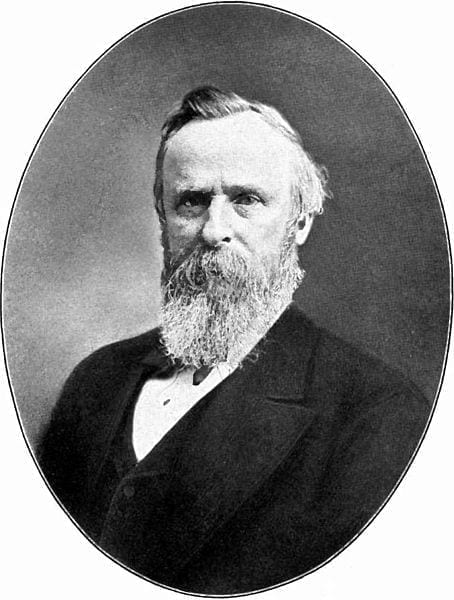

Thanksgiving Proclamation (1863)

October 03, 1863

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.