No related resources

Introduction

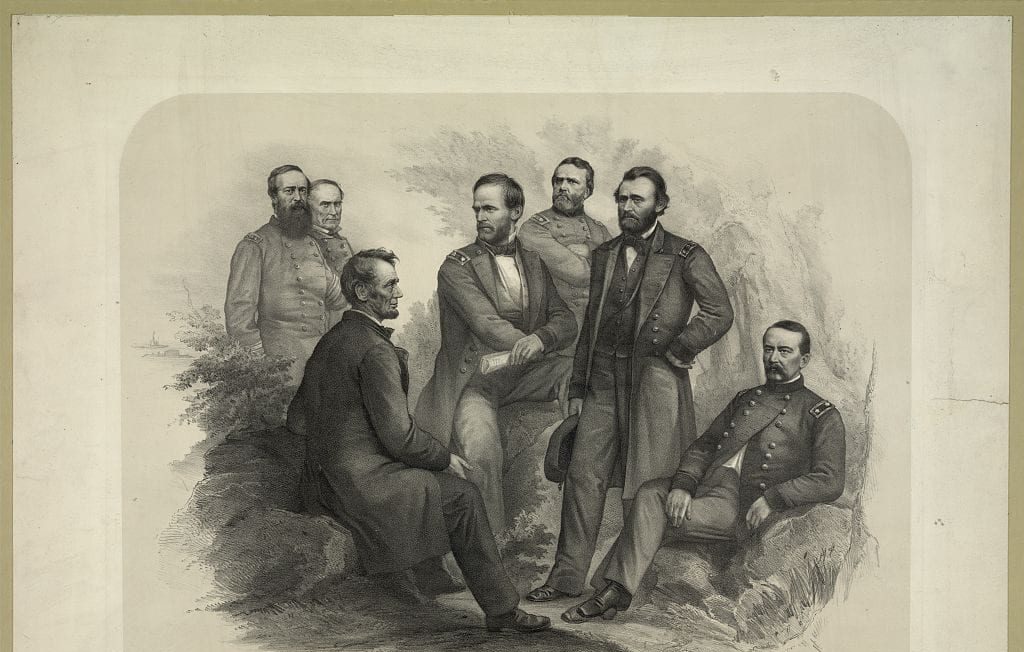

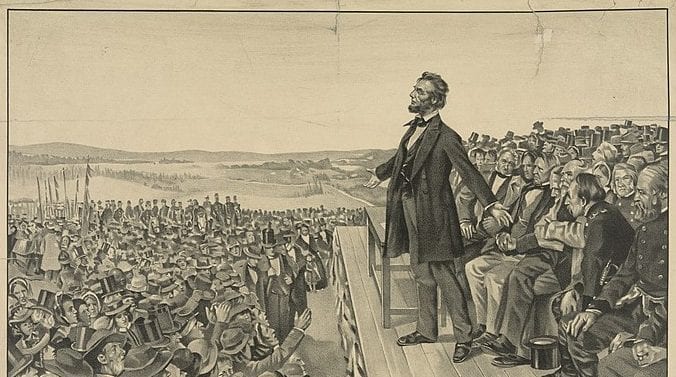

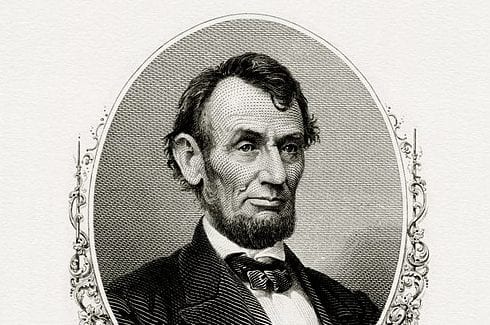

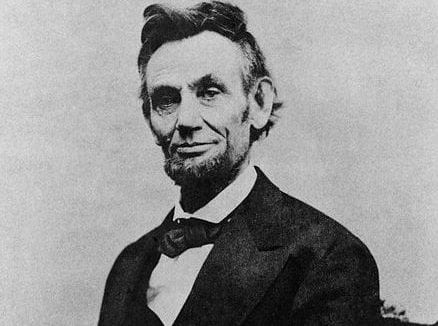

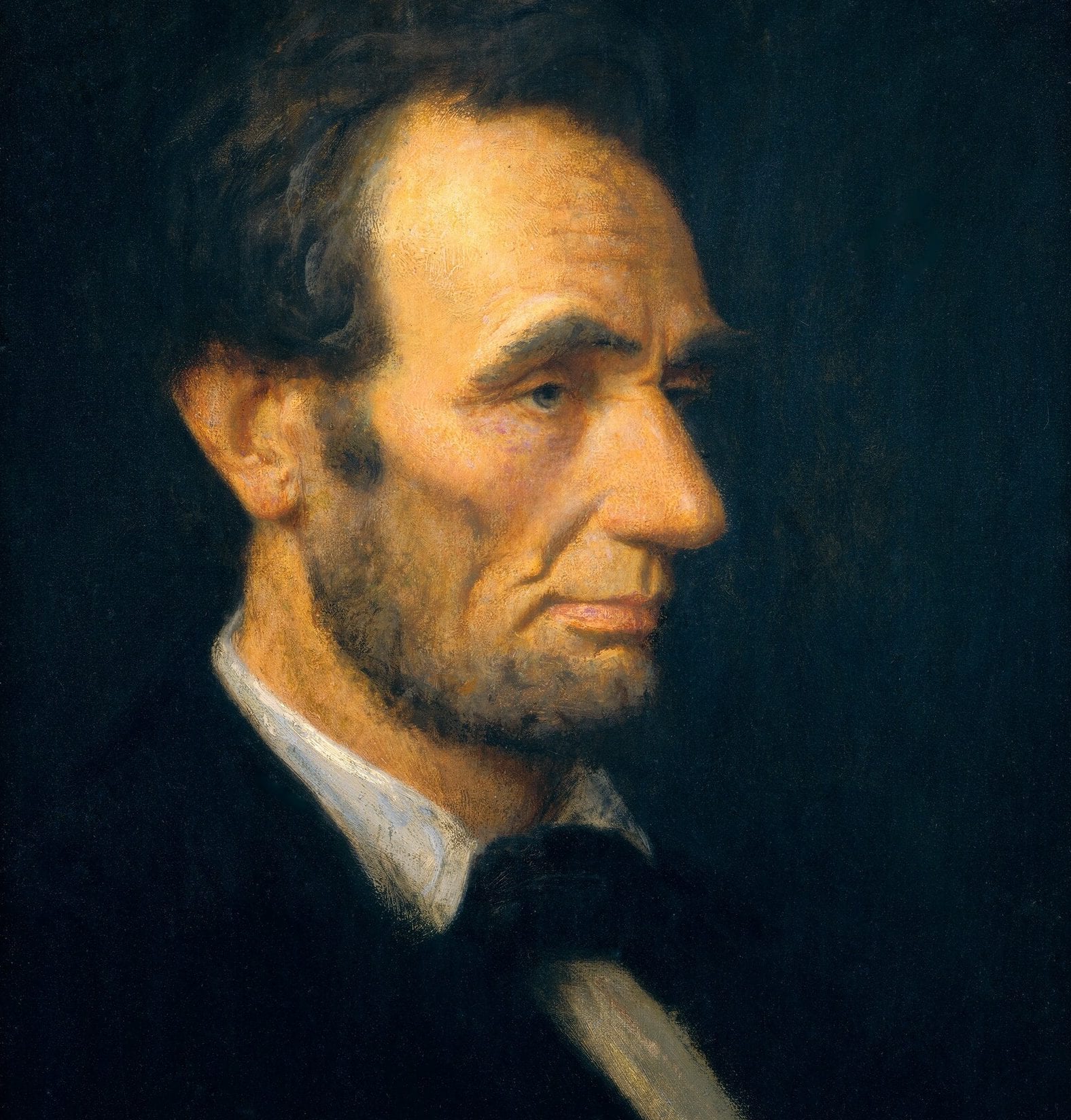

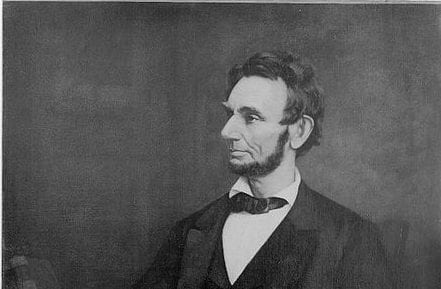

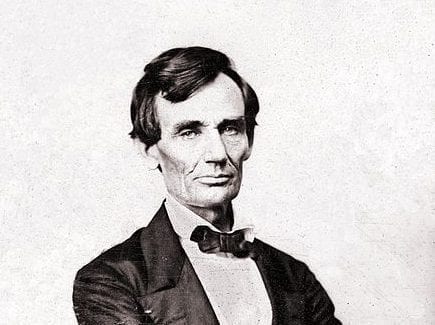

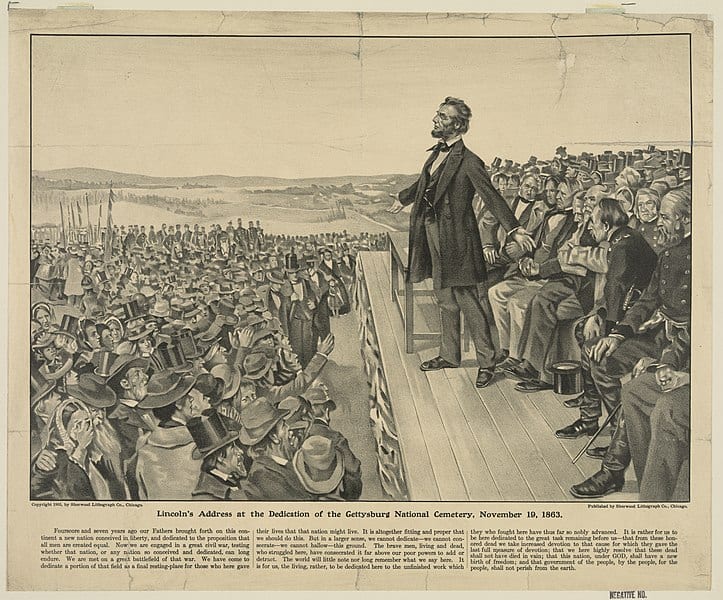

In April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports to be enforced by the US Navy against any ships carrying cargo to and from areas held by the Confederacy. The proclamation was made before Congress convened in July 1861 to adopt such measures. Under Lincoln’s order, the ships and their cargo were to be legally seized and forfeited as a “prize” under the law of nations regardless of the owners’ nationality or personal loyalty to the Union. A number of ships owned by British and Northern merchants were confiscated between April and July 1861. The merchants sued in federal court, arguing that President Lincoln lacked the constitutional authority to order the legal confiscation and forfeiture of their ships and cargo. By a narrow 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court sided with Lincoln.

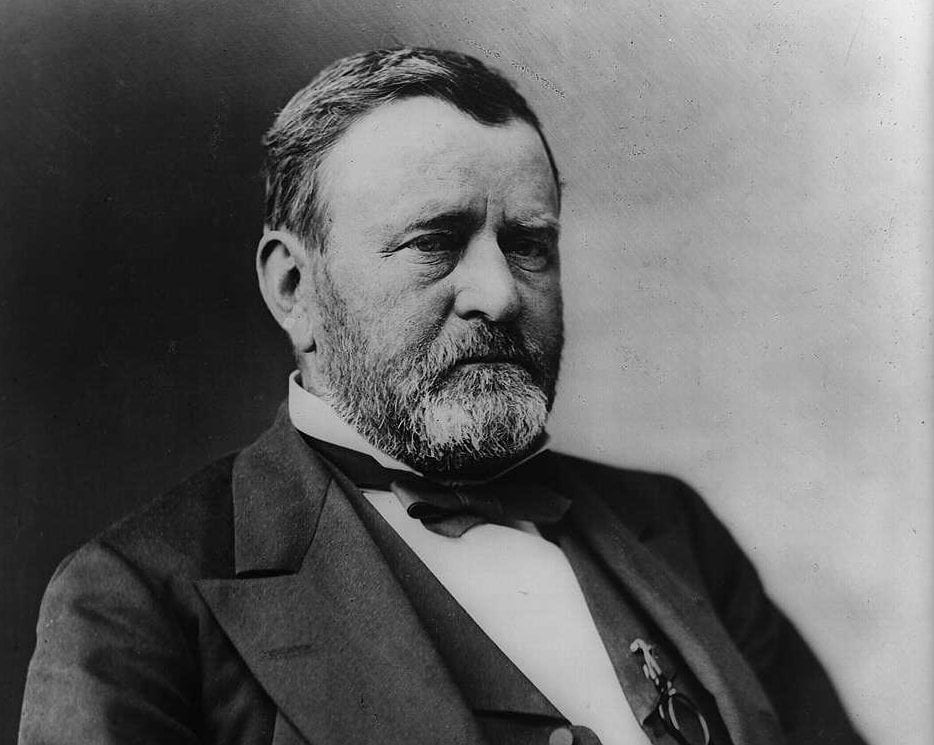

The Prize Cases has been cited often as a precedent for a broad reading of the president’s legal power in times of war and threats to national security. Three years later in Ex Parte Milligan (1866), however, the Supreme Court declared unanimously that the president’s power did not extend to establishing military tribunals for American citizens during a time of war where the federal courts are open and operating. Interestingly, all five of the justices who sided with Lincoln in The Prize Cases during the war ruled against him in the Milligan decision after the war.

Source: 67 U.S. 635; https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/67/635

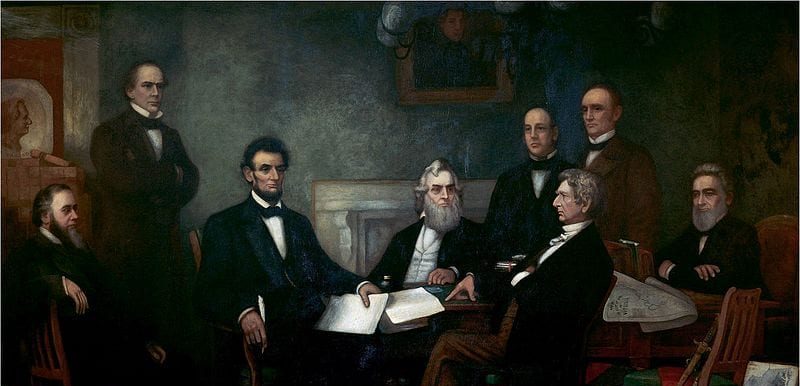

Justice GRIER delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by Justices WAYNE, SWAYNE, MILLER, and DAVIS.

. . . These were cases in which the vessels named, together with their cargoes, were severally captured and brought in as prizes by public ships of the United States. . . . In each case, the District Court pronounced a decree of condemnation, from which the claimants took an appeal . . . .

. . . Had the President a right to institute a blockade of ports in possession of persons in armed rebellion against the Government, on the principles of international law, as known and acknowledged among civilized States?

Was the property of persons domiciled or residing within those States a proper subject of capture on the sea as “enemies’ property”? . . .

That a blockade de facto actually existed, and was formally declared and notified by the President on the 27th and 30th of April, 1861, is an admitted fact in these cases.

That the President, as the Executive Chief of the Government and Commander-in-chief of the Army and Navy, was the proper person to make such notification has not been, and cannot be disputed.

The right of prize and capture has its origin in the “jus belli” [laws of war], and is governed and adjudged under the law of nations. To legitimate the capture of a neutral vessel or property on the high seas, a war must exist de facto, and the neutral must have knowledge or notice of the intention of one of the parties belligerent to use this mode of coercion against a port, city, or territory, in possession of the other.

Let us enquire whether, at the time this blockade was instituted, a state of war existed which would justify a resort to these means of subduing the hostile force.

War has been well defined [by Emerich de Vattel] to be, “That state in which a nation prosecutes its right by force.”

The parties belligerent in a public war are independent nations. But it is not necessary, to constitute war, that both parties should be acknowledged as independent nations or sovereign States. A war may exist where one of the belligerents claims sovereign rights as against the other.

Insurrection against a government may or may not culminate in an organized rebellion, but a civil war always begins by insurrection against the lawful authority of the Government. . . . When the party in rebellion occupy and hold in a hostile manner a certain portion of territory, have declared their independence, have cast off their allegiance, have organized armies have commenced hostilities against their former sovereign, the world acknowledges them as belligerents, and the contest a war. They claim to be in arms to establish their liberty and independence, in order to become a sovereign State, while the sovereign party treats them as insurgents and rebels who owe allegiance, and who should be punished with death for their treason.

The laws of war, as established among nations, have their foundation in reason, and all tend to mitigate the cruelties and misery produced by the scourge of war. Hence the parties to a civil war usually concede to each other belligerent rights. They exchange prisoners, and adopt the other courtesies and rules common to public or national wars. . . .

As a civil war is never publicly proclaimed, eo nomine,[1] against insurgents, its actual existence is a fact in our domestic history which the Court is bound to notice and to know.

The true test of its existence, as found in the writings of the sages of the common law, may be thus summarily stated: “When the regular course of justice is interrupted by revolt, rebellion, or insurrection, so that the Courts of Justice cannot be kept open, civil war exists, and hostilities may be prosecuted on the same footing as if those opposing the Government were foreign enemies invading the land.”

By the Constitution, Congress alone has the power to declare a national or foreign war. . . . The Constitution confers on the President the whole Executive power. He is bound to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. He is Commander-in-chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several States when called into the actual service of the United States. He has no power to initiate or declare a war either against a foreign nation or a domestic State. But, by the Acts of Congress of February 28th, 1795, and 3d of March, 1807, he is authorized to call out the militia and use the military and naval forces of the United States in case of invasion by foreign nations, and to suppress insurrection against the government of a State or of the United States.

If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the President is not only authorized but bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war, but is bound to accept the challenge without waiting for any special legislative authority. And whether the hostile party be a foreign invader or States organized in rebellion, it is nonetheless a war although the declaration of it be “unilateral.” . . .

This greatest of civil wars was not gradually developed by popular commotion, tumultuous assemblies, or local unorganized insurrections. However long may have been its previous conception, it nevertheless sprung forth suddenly from the parent brain, a Minerva in the full panoply of war. The President was bound to meet it in the shape it presented itself, without waiting for Congress to baptize it with a name; and no name given to it by him or them could change the fact. . . ..

As soon as the news of the attack on Fort Sumter, and the organization of a government by the seceding States, assuming to act as belligerents, could become known in Europe, to-wit, on the 13th of May, 1861, the Queen of England issued her proclamation of neutrality, “recognizing hostilities as existing between the Government of the United States of America and certain States styling themselves the Confederate States of America.” This was immediately followed by similar declarations or silent acquiescence by other nations.

After such an official recognition by the sovereign, a citizen of a foreign State is estopped[2] to deny the existence of a war with all its consequences as regards neutrals. They cannot ask a Court to affect a technical ignorance of the existence of a war, which all the world acknowledges to be the greatest civil war known in the history of the human race, and thus cripple the arm of the Government and paralyze its power by subtle definitions and ingenious sophisms.

The law of nations is also called the law of nature; it is founded on the common consent as well as the common sense of the world. It contains no such anomalous doctrine as that which this Court are now for the first time desired to pronounce, to-wit, that insurgents who have risen in rebellion against their sovereign, expelled her Courts, established a revolutionary government, organized armies, and commenced hostilities, are not enemies because they are traitors, and a war levied on the Government by traitors, in order to dismember and destroy it, is not a war because it is an “insurrection.”

Whether the President, in fulfilling his duties as Commander-in-chief in suppressing an insurrection, has met with such armed hostile resistance and a civil war of such alarming proportions as will compel him to accord to them the character of belligerents is a question to be decided by him, and this Court must be governed by the decisions and acts of the political department of the Government to which this power was entrusted. “He must determine what degree of force the crisis demands.” The proclamation of blockade is itself official and conclusive evidence to the Court that a state of war existed which demanded and authorized a recourse to such a measure under the circumstances peculiar to the case. . . .

On this first question, therefore, we are of the opinion that the President had a right, jure belli, to institute a blockade of ports in possession of the States in rebellion which neutrals are bound to regard.

We come now to the consideration of the second question. What is included in the term “enemies’ property”?

Is the property of all persons residing within the territory of the States now in rebellion, captured on the high seas, to be treated as “enemies’ property” whether the owner be in arms against the Government or not?

The right of one belligerent not only to coerce the other by direct force, but also to cripple his resources by the seizure or destruction of his property, is a necessary result of a state of war. Money and wealth, the products of agriculture and commerce, are said to be the sinews of war, and as necessary in its conduct as numbers and physical force. Hence it is that the laws of war recognize the right of a belligerent to cut these sinews of the power of the enemy by capturing his property on the high seas. . . .

[The owners of the ships insist] that insurrection is the act of individuals and not of a government or sovereignty; that the individuals engaged are subjects of law. That confiscation of their property can be effected only under a municipal law. That, by the law of the land, such confiscation cannot take place without the conviction of the owner of some offense, and finally that the secession ordinances are nullities, and ineffectual to release any citizen from his allegiance to the national Government, and consequently that the Constitution and Laws of the United States are still operative over persons in all the States for punishment as well as protection. . . .

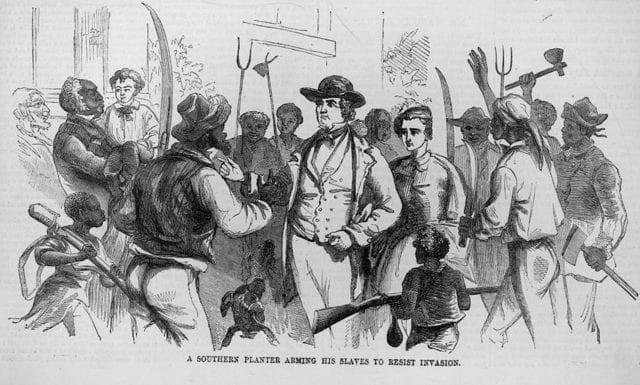

[However, those] organizing this rebellion . . . have acted as States claiming to be sovereign over all persons and property within their respective limits, and asserting a right to absolve their citizens from their allegiance to the Federal Government. Several of these States have combined to form a new confederacy, claiming to be acknowledged by the world as a sovereign State. Their right to do so is now being decided by wager of battle. The ports and territory of each of these States are held in hostility to the General Government. It is no loose, unorganized insurrection, having no defined boundary or possession. It has a boundary marked by lines of bayonets, and which can be crossed only by force—south of this line is enemies’ territory, because it is claimed and held in possession by an organized, hostile and belligerent power.

All persons residing within this territory whose property may be used to increase the revenues of the hostile power are, in this contest, liable to be treated as enemies, though not foreigners. They have cast off their allegiance and made war on their Government, and are none the less enemies because they are traitors. . . .

Whether property be liable to capture as “enemies’ property” does not in any manner depend on the personal allegiance of the owner. It is the illegal traffic that stamps it as “enemies’ property.” It is of no consequence whether it belongs to an ally or a citizen. The owner, pro hac vice,[3] is an enemy.

The produce of the soil of the hostile territory, as well as other property engaged in the commerce of the hostile power, as the source of its wealth and strength, are always regarded as legitimate prize, without regard to the domicil of the owner, and much more so if he reside and trade within their territory. . . .

Justice NELSON dissenting, joined by Chief Justice TANEY and Justices CATRON and CLIFFORD.

. . . [An] objection taken to the seizure of this vessel and cargo is that there was no existing war between the United States and the States in insurrection within the meaning of the law of nations, which drew after it the consequences of a public or civil war. A contest by force between independent sovereign States is called a public war, and, when duly commenced by proclamation or otherwise, it entitles both of the belligerent parties to all the rights of war against each other, and as respects neutral nations. . . .

This power in all civilized nations is regulated by the fundamental laws or municipal constitution of the country.

By our constitution, this power is lodged in Congress. Congress shall have power “to declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water.” . . .

In the case of a rebellion or resistance of a portion of the people of a country against the established government, there is no doubt, if in its progress and enlargement the government thus sought to be overthrown sees fit, it may by the competent power recognize or declare the existence of a state of civil war, which will draw after it all the consequences and rights of war between the contending parties as in the case of a public war. . . . But before this insurrection against the established Government can be dealt with on the footing of a civil war, within the meaning of the law of nations and the Constitution of the United States, and which will draw after it belligerent rights, it must be recognized or declared by the war-making power of the Government. No power short of this can change the legal status of the Government or the relations of its citizens from that of peace to a state of war, or bring into existence all those duties and obligations of neutral third parties growing out of a state of war. The war power of the Government must be exercised before this changed condition of the Government and people and of neutral third parties can be admitted. There is no difference in this respect between a civil or a public war. . . .

An idea seemed to be entertained that all that was necessary to constitute a war was organized hostility in the district or country in a state of rebellion—that . . . the magnitude and dimensions of the resistance against the Government— constituted war with all the belligerent rights belonging to civil war. . . .

Now, in one sense, no doubt this is war, and may be a war of the most extensive and threatening dimensions and effects. . . . [But] to constitute a civil war in the sense in which we are speaking, before it can exist in contemplation of law, it must be recognized or declared by the sovereign power of the State, and which sovereign power by our Constitution is lodged in the Congress of the United States—civil war, therefore, under our system of government, can exist only by an act of Congress, which requires the assent of two of the great departments of the Government, the Executive and Legislative.

We have thus far been speaking of the war power under the Constitution of the United States, and as known and recognized by the law of nations. But we are asked, what would become of the peace and integrity of the Union in case of an insurrection at home or invasion from abroad if this power could not be exercised by the President in the recess of Congress, and until that body could be assembled?

The framers of the Constitution fully comprehended this question, and provided for the contingency. Indeed, it would have been surprising if they had not, as a rebellion had occurred in the State of Massachusetts while the Convention was in session, and which had become so general that it was quelled only by calling upon the military power of the State. The Constitution declares that Congress shall have power “to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.” Another clause, “that the President shall be Commander-in-chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several States when called into the actual service of United States”; and, again, “He shall take care that the laws shall be faithfully executed.” Congress passed laws on this subject in 1792 and 1795.

[The last Act] provides that when the laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution obstructed in any State by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the course of judicial proceedings, it shall be lawful for the President to call forth the militia of such State, or of any other State or States as may be necessary to suppress such combinations. . . .

It will be seen, therefore, that ample provision has been made under the Constitution and laws against any sudden and unexpected disturbance of the public peace from insurrection at home or invasion from abroad. The whole military and naval power of the country is put under the control of the President to meet the emergency. . . . It is the exercise of a power under the municipal laws of the country and not under the law of nations, and, as we see, furnishes the most ample means of repelling attacks from abroad or suppressing disturbances at home until the assembling of Congress, who can, if it be deemed necessary, bring into operation the war power, and thus change the nature and character of the contest. Then, instead of being carried on under the municipal law of 1795, it would be under the law of nations, and the Acts of Congress as war measures with all the rights of war. . . .

In the breaking out of a rebellion against the established Government, the usage in all civilized countries, in its first stages, is to suppress it by confining the public forces and the operations of the Government against those in rebellion, and at the same time extending encouragement and support to the loyal people with a view to their cooperation in putting down the insurgents. This course is not only the dictate of wisdom, but of justice. . . . It [was] a personal war against the individuals engaged in resisting the authority of the Government . . . until Congress assembled and acted upon this state of things.

Down to this period the only enemy recognized by the Government was the persons engaged in the rebellion; all others were peaceful citizens, entitled to all the privileges of citizens under the Constitution. Certainly it cannot rightfully be said that the President has the power to convert a loyal citizen into a belligerent enemy or confiscate his property as enemy’s property.

Congress assembled on the call for an extra session the 4th of July, 1861, and among the first acts passed was one in which the President was authorized by proclamation to interdict all trade and intercourse between all the inhabitants of States in insurrection and the rest of the United States, subjecting vessel and cargo to capture and condemnation as prize, and also to direct the capture of any ship or vessel belonging in whole or in part to any inhabitant of a State whose inhabitants are declared by the proclamation to be in a state of insurrection, found at sea or in any part of the rest of the United States. . . .

This Act of Congress [of 13th of July, 1861], we think, recognized a state of civil war between the Government and the Confederate States, and made it territorial. . . .

. . . [W]hen the Government of the United States recognizes a state of civil war to exist between a foreign nation and her colonies, but remaining itself neutral, the Courts are bound to consider as lawful all those acts which the new Government may direct against the enemy, and we admit the President who conducts the foreign relations of the Government may fitly recognize or refuse to do so, the existence of civil war in the foreign nation under the circumstances stated.

But this is a very different question from the one before us, which is whether the President can recognize or declare a civil war, under the Constitution, with all its belligerent rights, between his own Government and a portion of its citizens in a state of insurrection. That power, as we have seen, belongs to Congress. We agree when such a war is recognized or declared to exist by the warmaking power, but not otherwise, it is the duty of the Courts to follow the decision of the political power of the Government. . . .

Upon the whole, after the most careful consideration of this case which the pressure of other duties has admitted, I am compelled to the conclusion that no civil war existed between this Government and the States in insurrection till recognized by the Act of Congress 13th of July, 1861; that the President does not possess the power under the Constitution to declare war or recognize its existence within the meaning of the law of nations, which carries with it belligerent rights, and thus change the country and all its citizens from a state of peace to a state of war; that this power belongs exclusively to the Congress of the United States, and, consequently, that the President had no power to set on foot a blockade under the law of nations, and that the capture of the vessel and cargo in this case, and in all cases before us in which the capture occurred before the 13th of July, 1861, for breach of blockade, or as enemies’ property, are illegal and void, and that the decrees of condemnation should be reversed and the vessel and cargo restored.

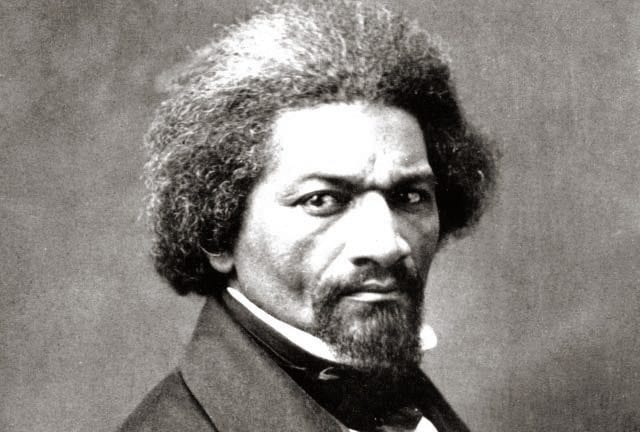

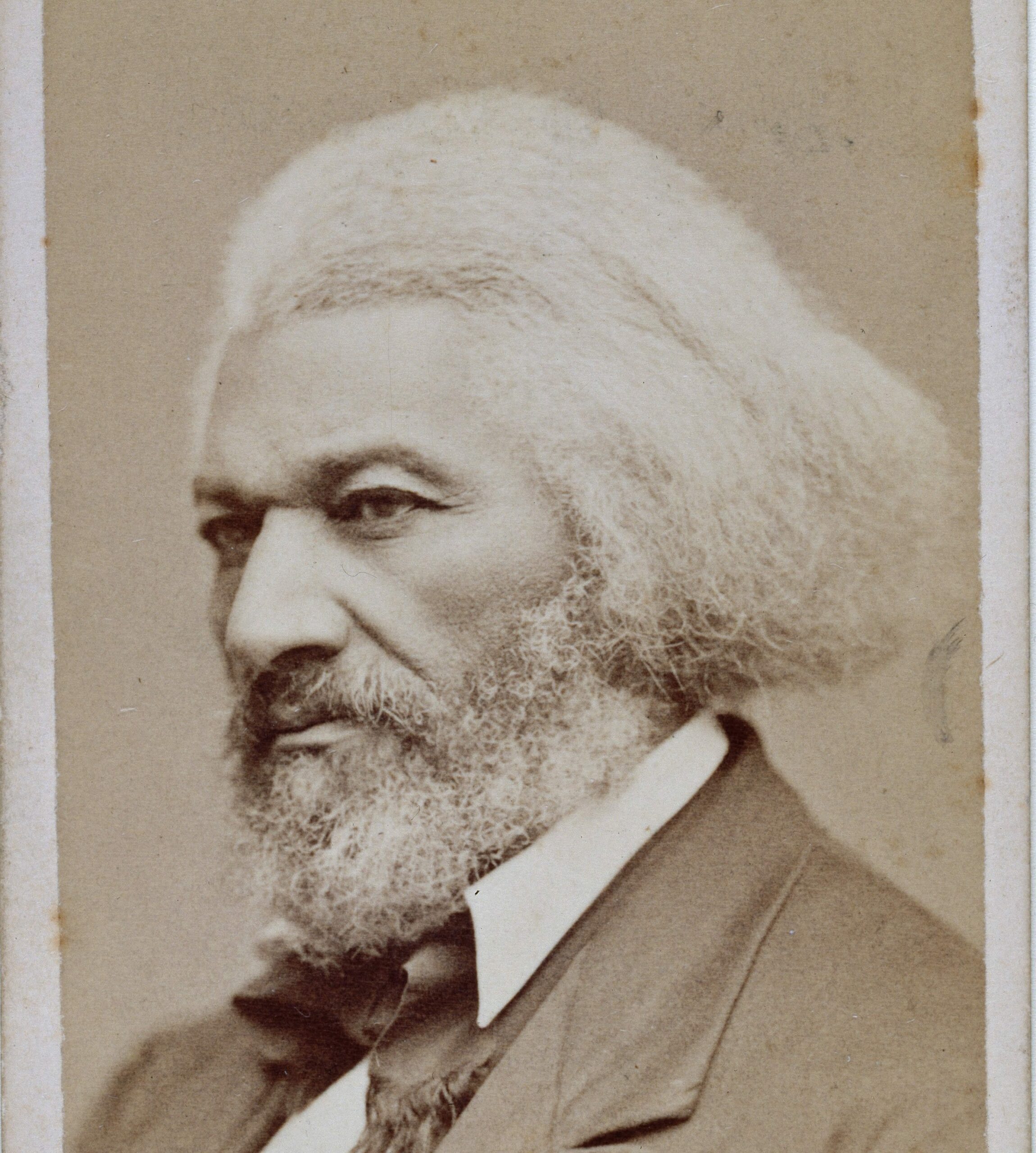

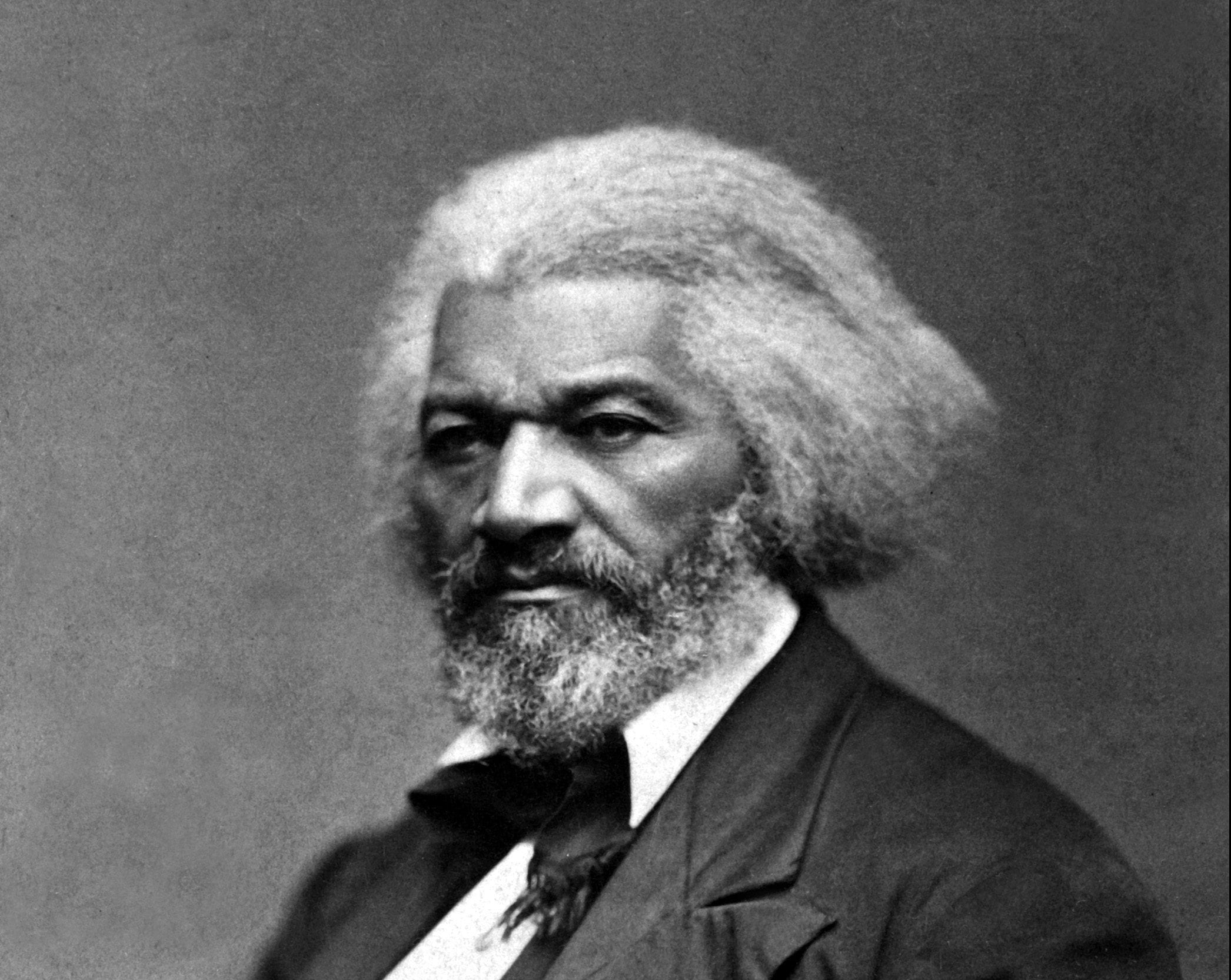

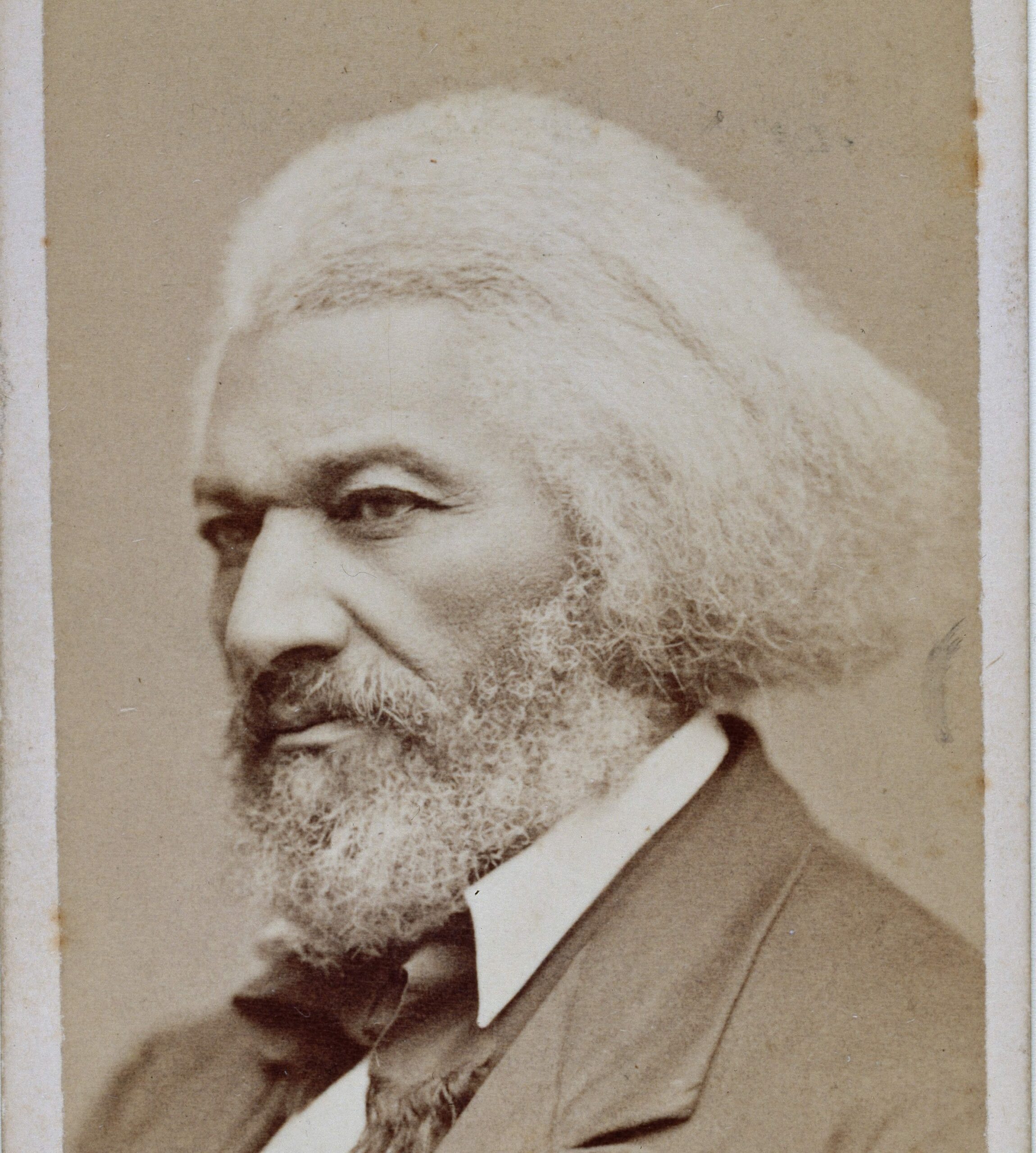

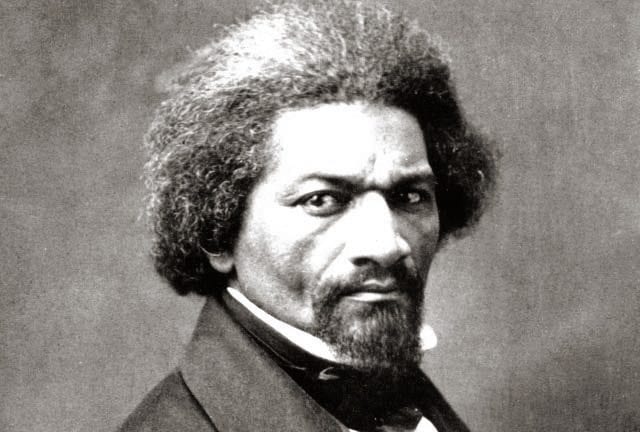

Men of Color, To Arms!

March 21, 1863

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.