Introduction

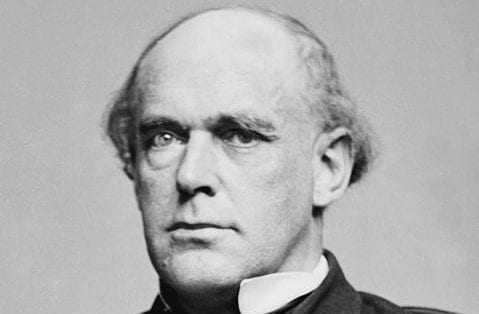

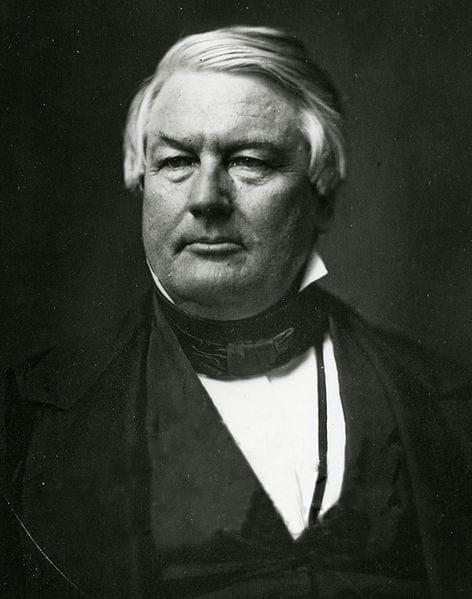

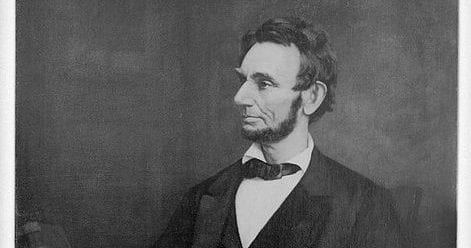

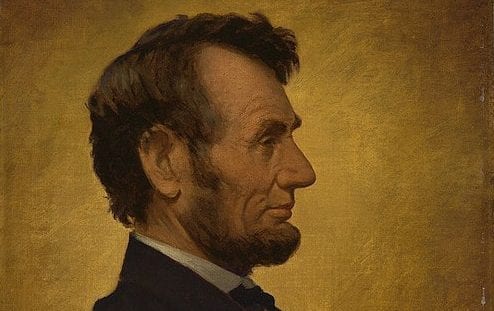

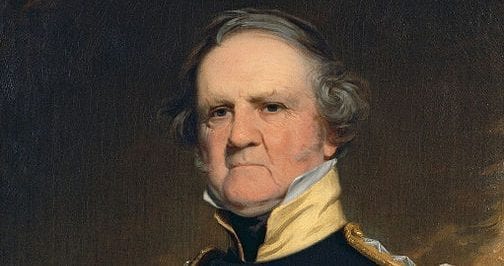

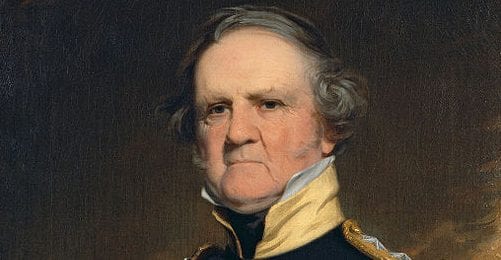

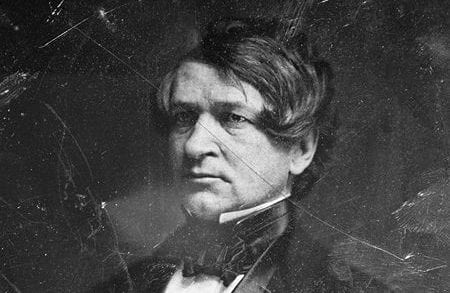

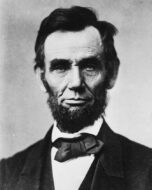

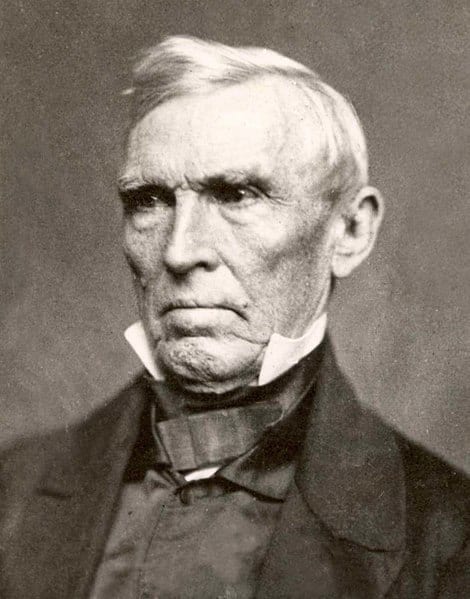

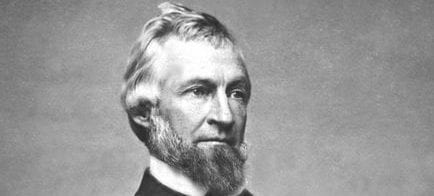

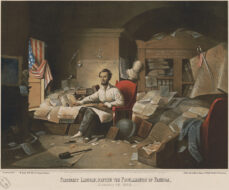

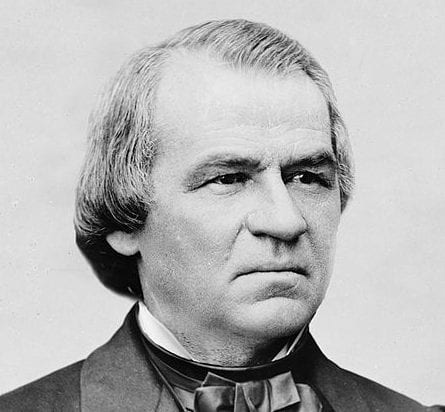

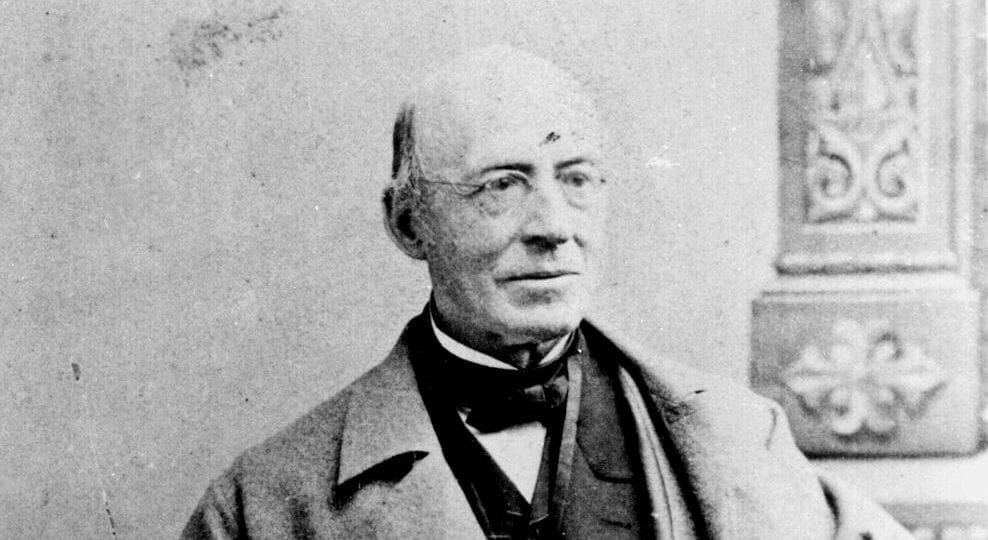

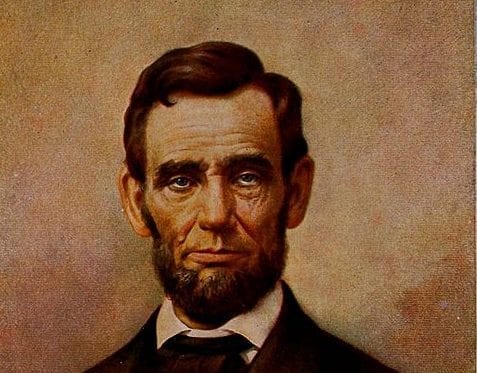

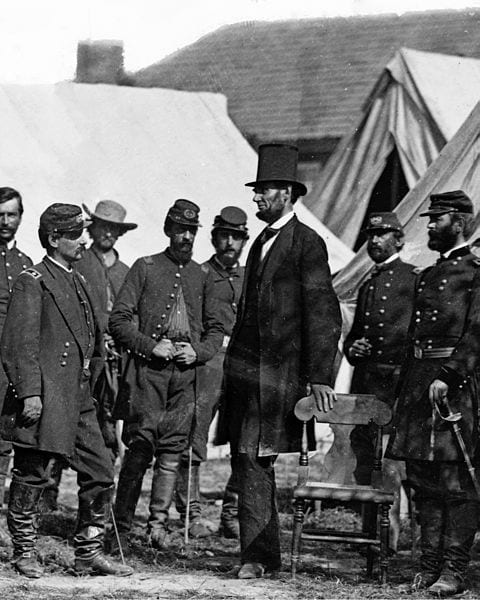

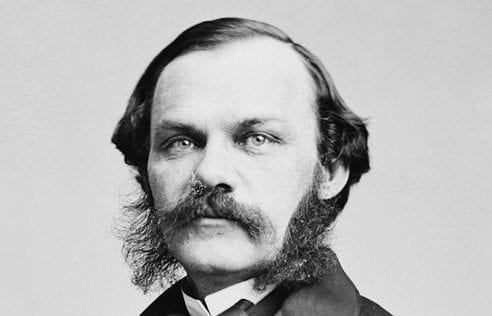

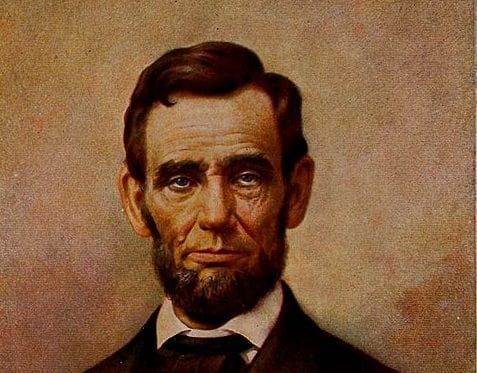

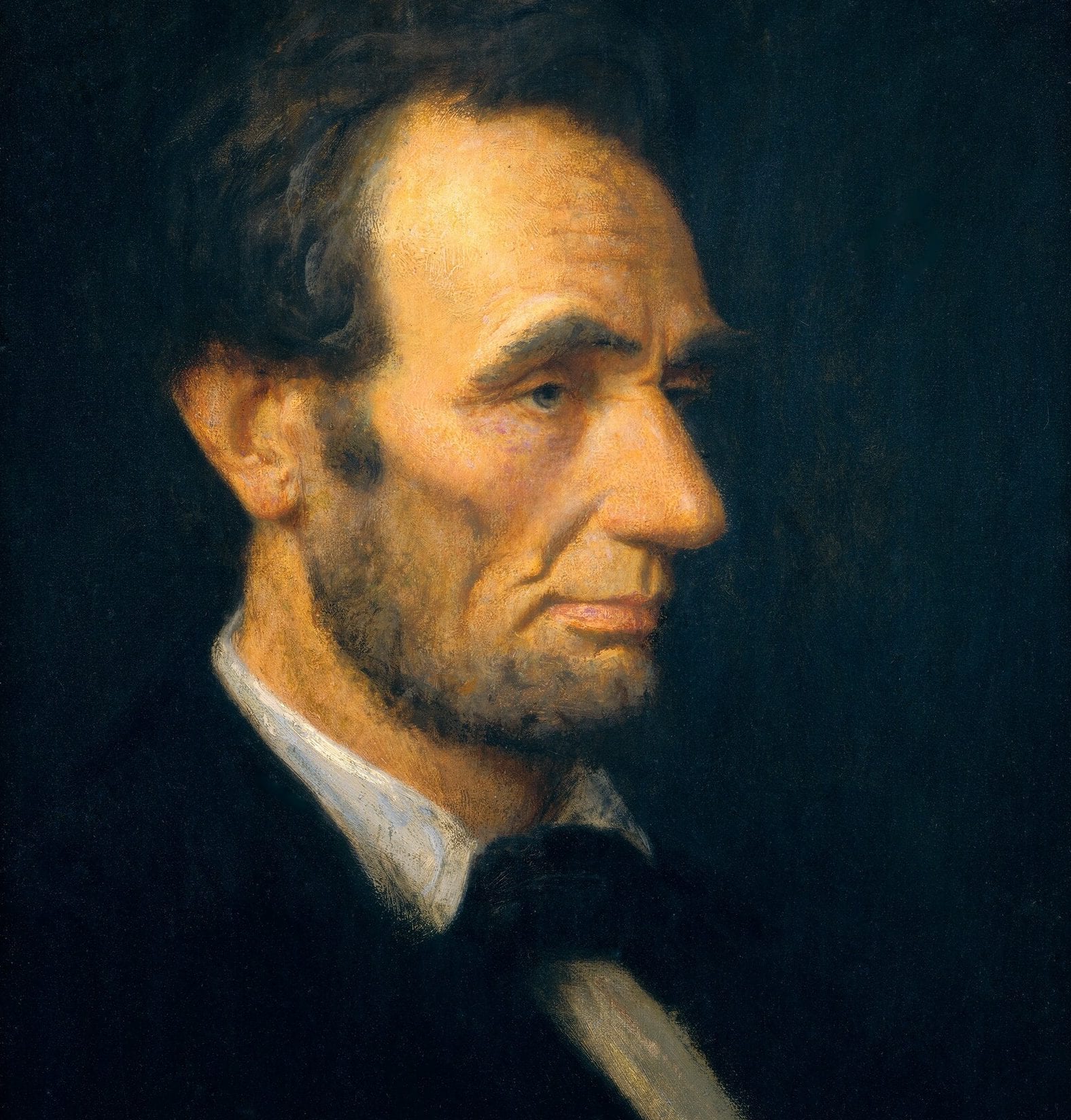

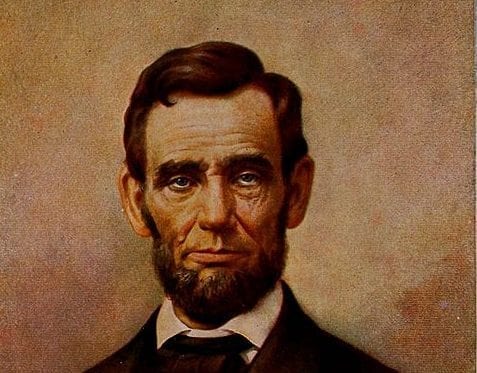

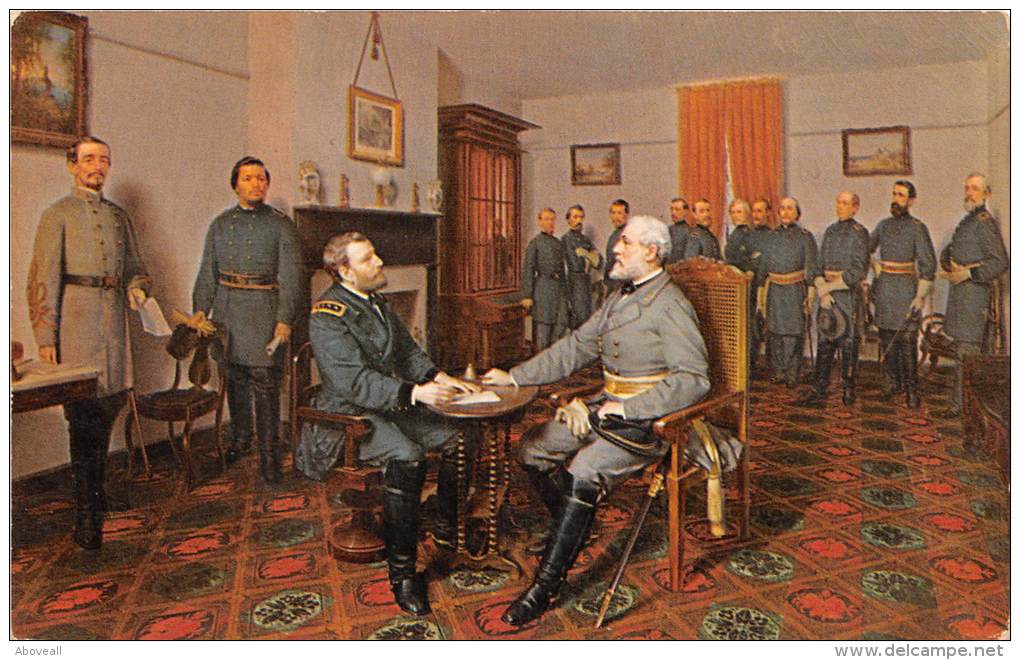

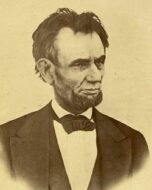

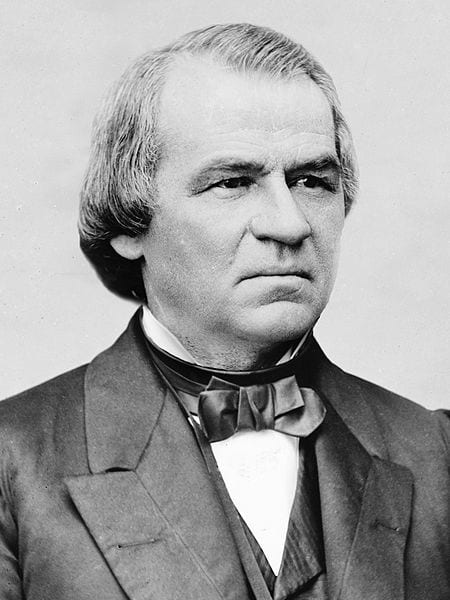

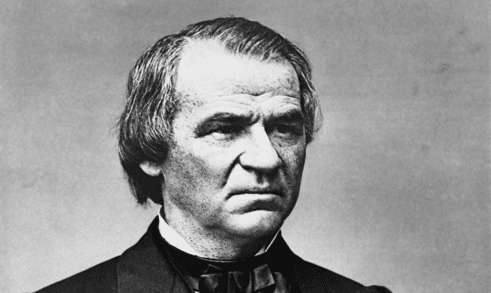

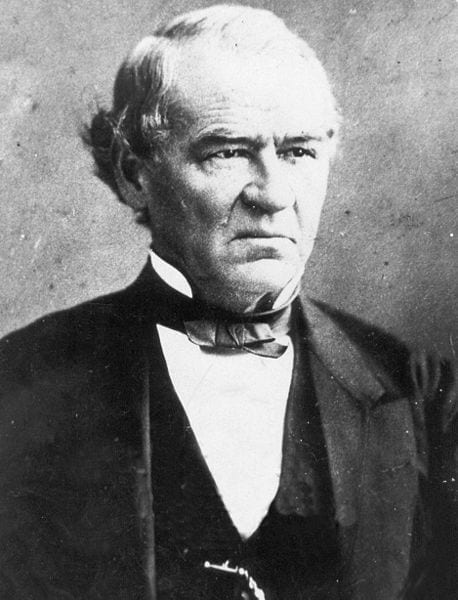

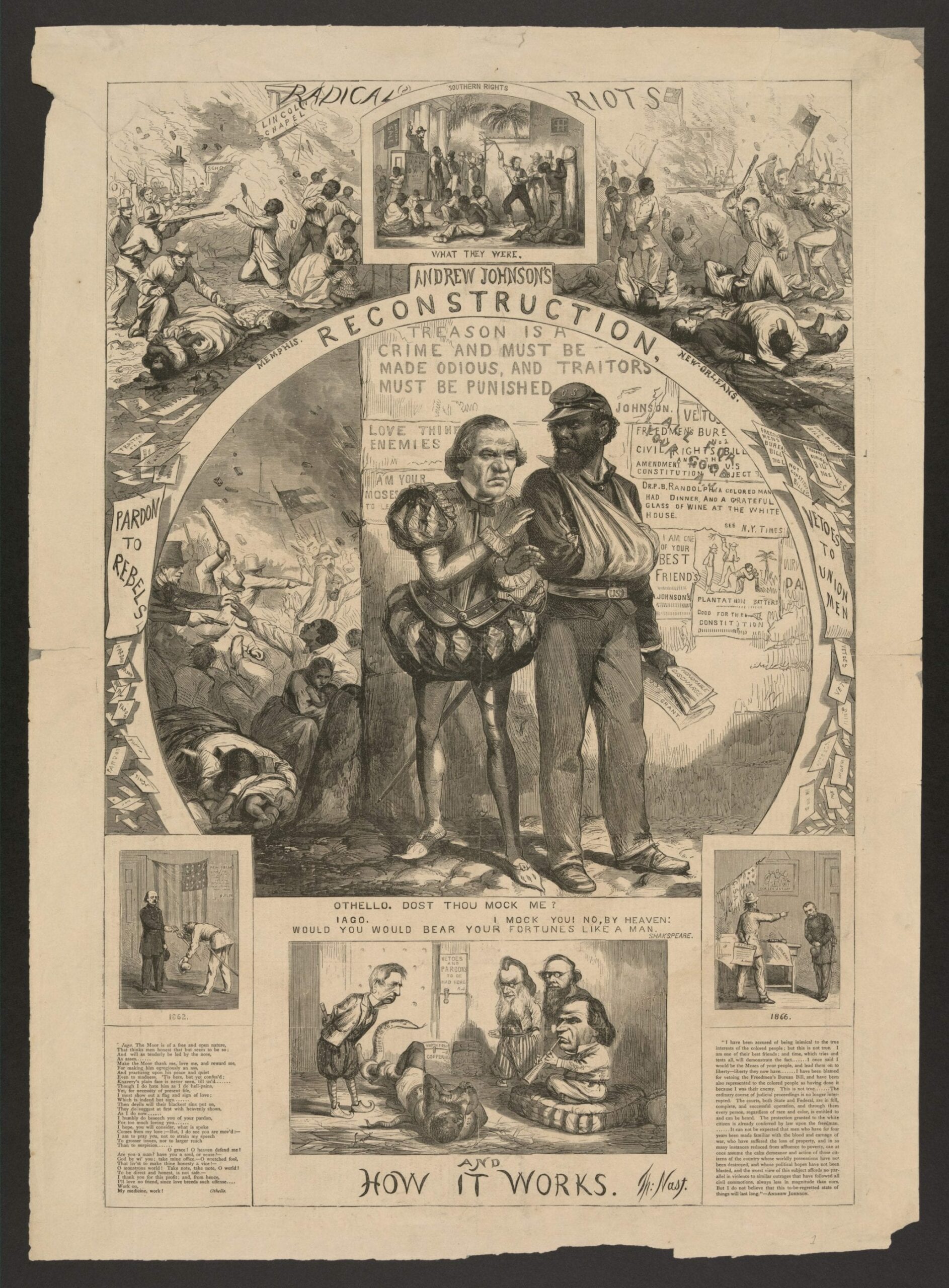

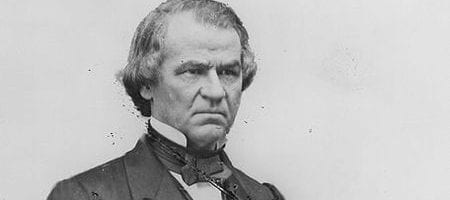

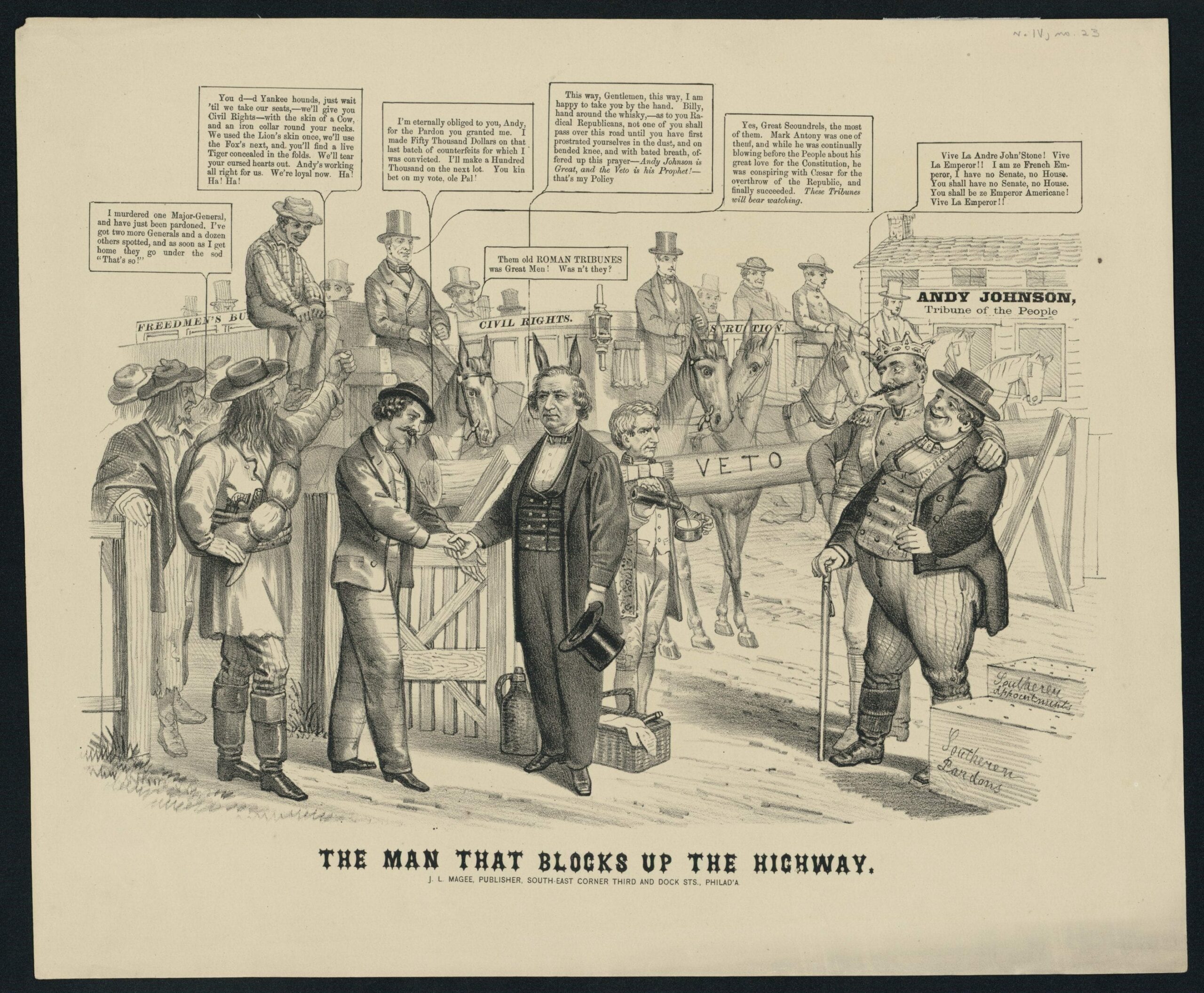

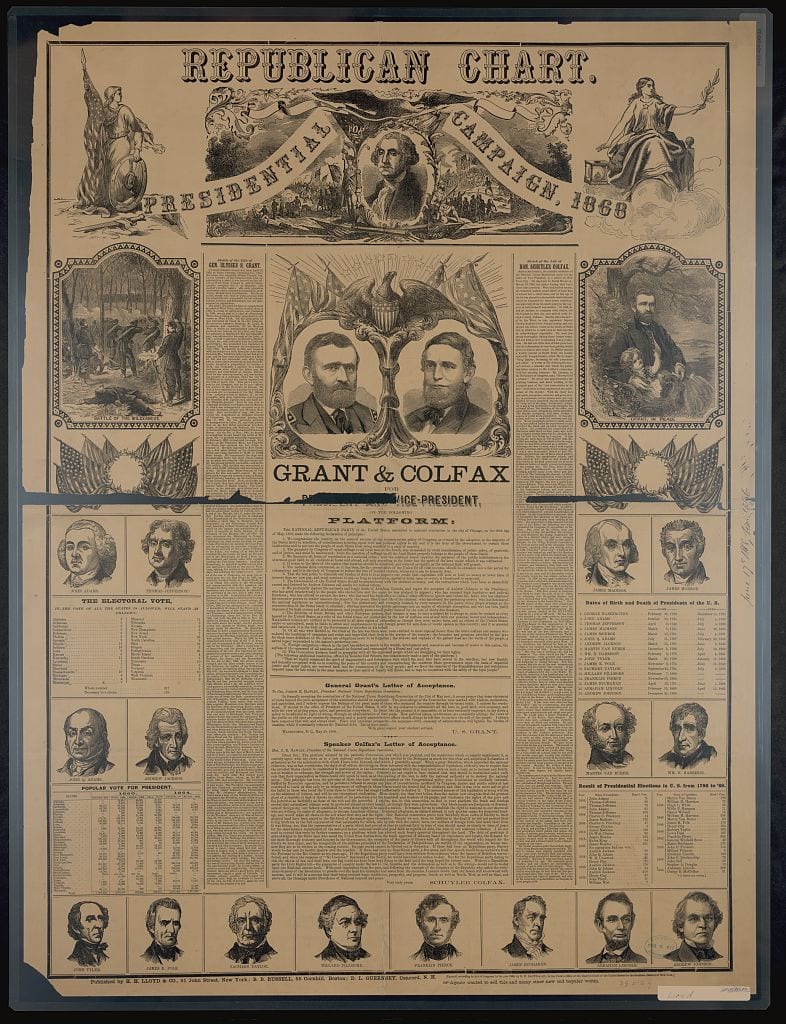

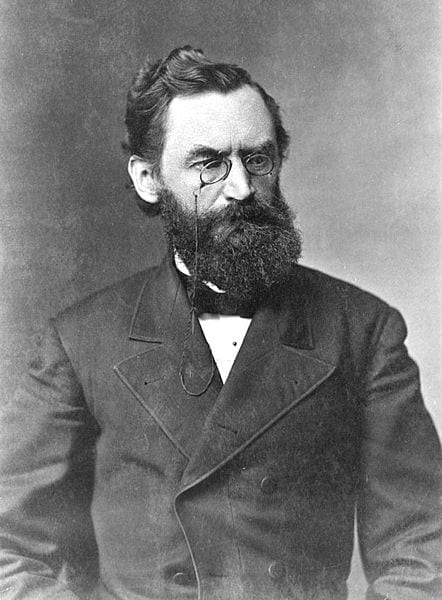

Richard Henry Dana (1815-1882) was a Boston blue blood – from a family of long standing. After gaining notoriety as an author, he became a lawyer. He practiced maritime law and assisted fugitive slaves in gaining as much protection as they could in antebellum America. When the Civil War broke out, he served in the Attorney General’s office. He successfully argued the government’s position in The Prize Cases, arguing that the Union blockade of Southern ports was justified within the Constitution and the laws of war. He resigned his office after President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, fearing President Andrew Johnson would not push the issue of reconstruction far enough. When Johnson announced his reconstruction policies for North Carolina and Mississippi, Dana, then a private citizen, put forward a powerful critique of them at a public meeting in Boston.

Source: Richard Henry Dana, “Grasp of War,” in Speeches in Stirring Times and Letters to a Son (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1910), pp. 243-259.

. . . We wish to know, I suppose, first, What are our powers? That is the first question – what are our just powers? Second – What ought we to do? Third – How ought we to do it? . . . .

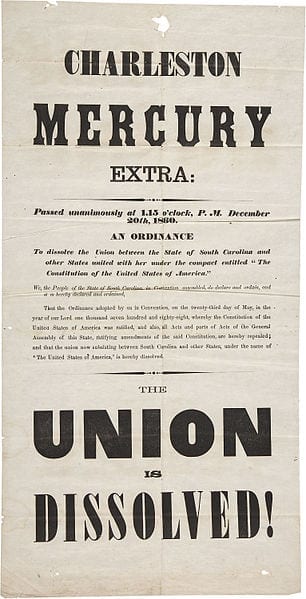

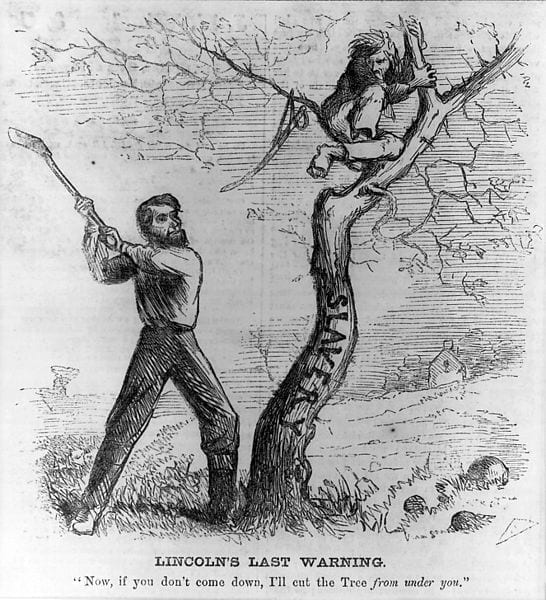

. . . [First], what are those powers and rights? What is a war? War is not an attempt to kill, to destroy; but it is coercion for a purpose. When a nation goes into war, she does it to secure an end, and the war does not cease until the end is secured. A boxing-match, a trial of strength or skill, is over when one party stops. A war is over when its purpose is secured. It is a fatal mistake to hold that this war is over, because the fighting has ceased. [Applause.] This war is not over. We are in the attitude and in the status of war to-day. There is the solution of this question. Why, suppose a man has attacked your life, my friend, in the highway, at night, armed, and after a death-struggle, you get him down – what then? When he says he has done fighting, are you obliged to release him? Can you not hold him until you have got some security against his weapons? [Applause.] Can you not hold him until you have searched him, and taken his weapons from him? Are you obliged to let him up to begin a new fight for your life? The same principle governs war between nations. When one nation has conquered another, in a war, the victorious nation does not retreat from the country and give up possession of it, because the fighting has ceased. No; it holds the conquered enemy in the grasp of war until it has secured whatever it has a right to require. [Applause.] I put that proposition fearlessly – The conquering part may hold the other in the grasp of war until it has secured whatever it has a right to require.

But what have we a right to require? . . . We have a right to require whatever the public safety and public faith make necessary. [Applause.] That is the proposition. Then, we come to this: We have a right to hold the rebels in the grasp of war until we have obtained whatever the public safety and the public faith require. [Applause, and cries of “good.”] Is not that a solid foundation to stand upon? Will it not bear examination? and are we not upon it to-day?

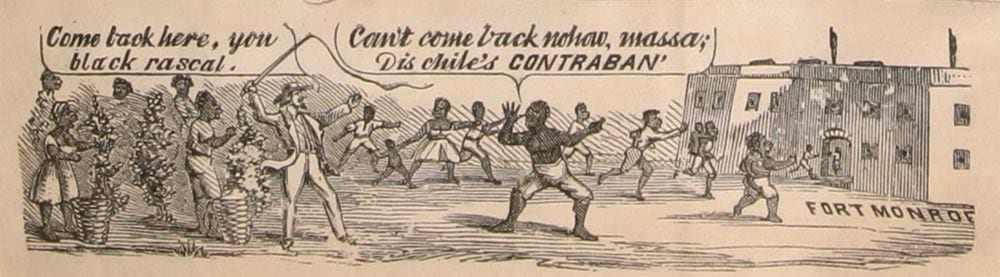

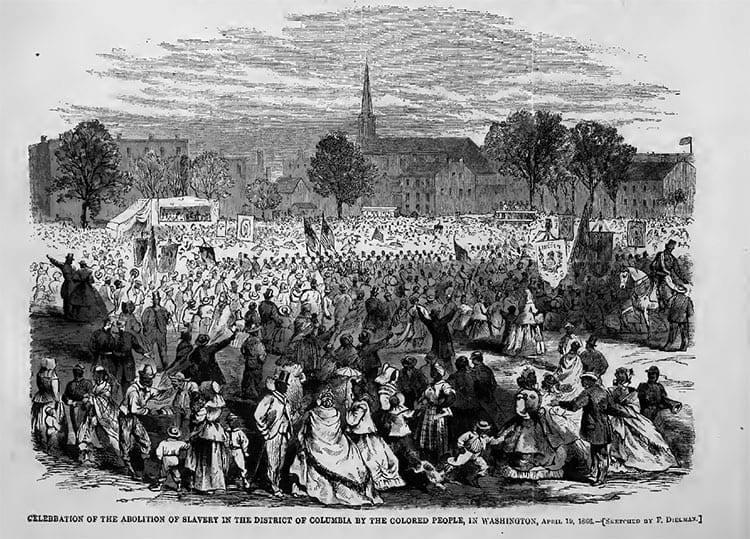

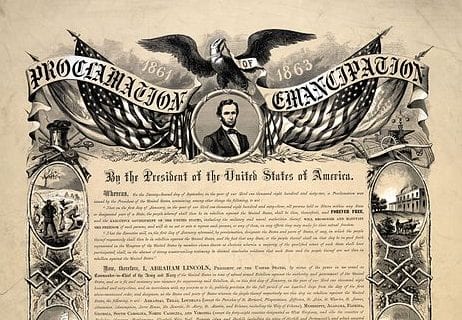

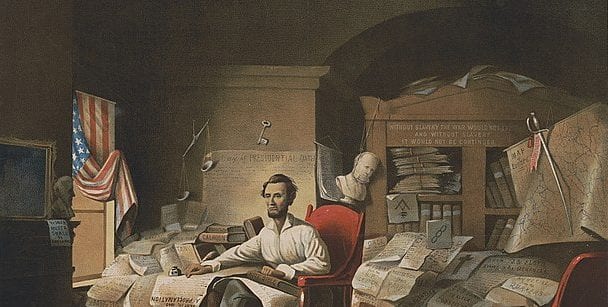

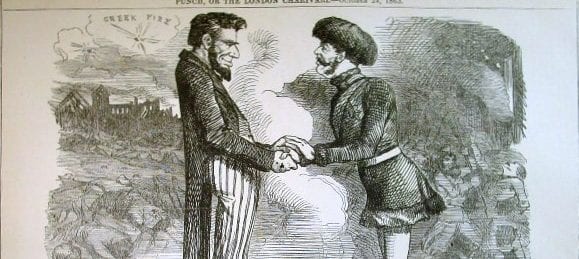

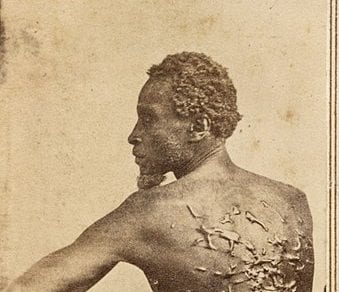

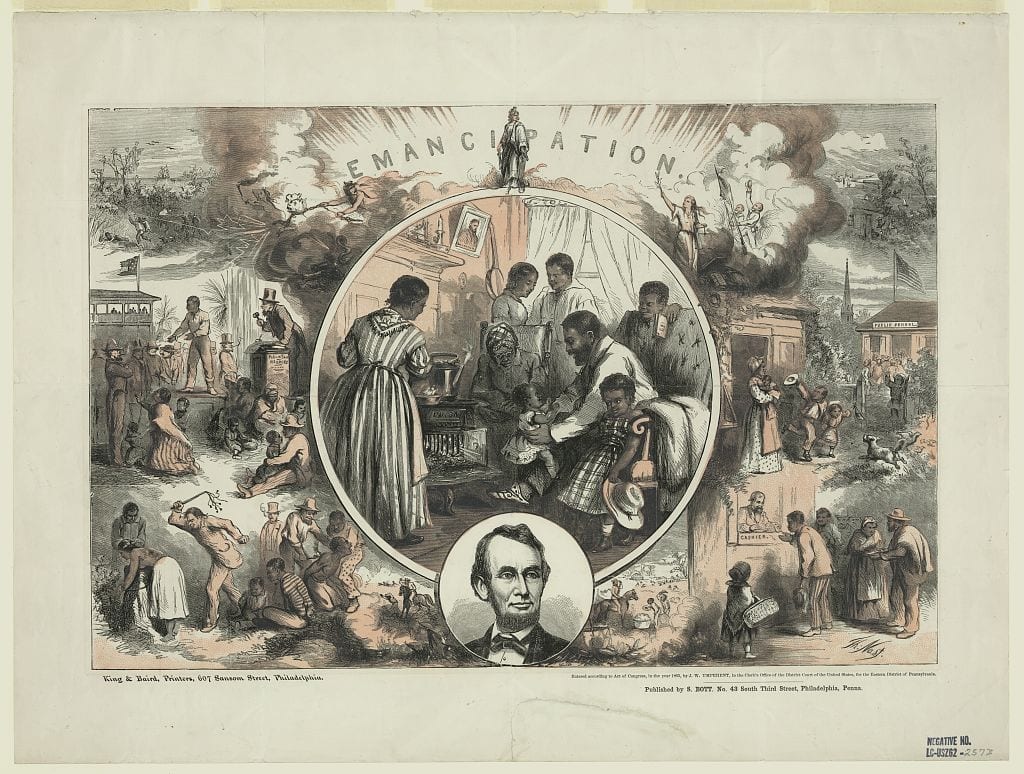

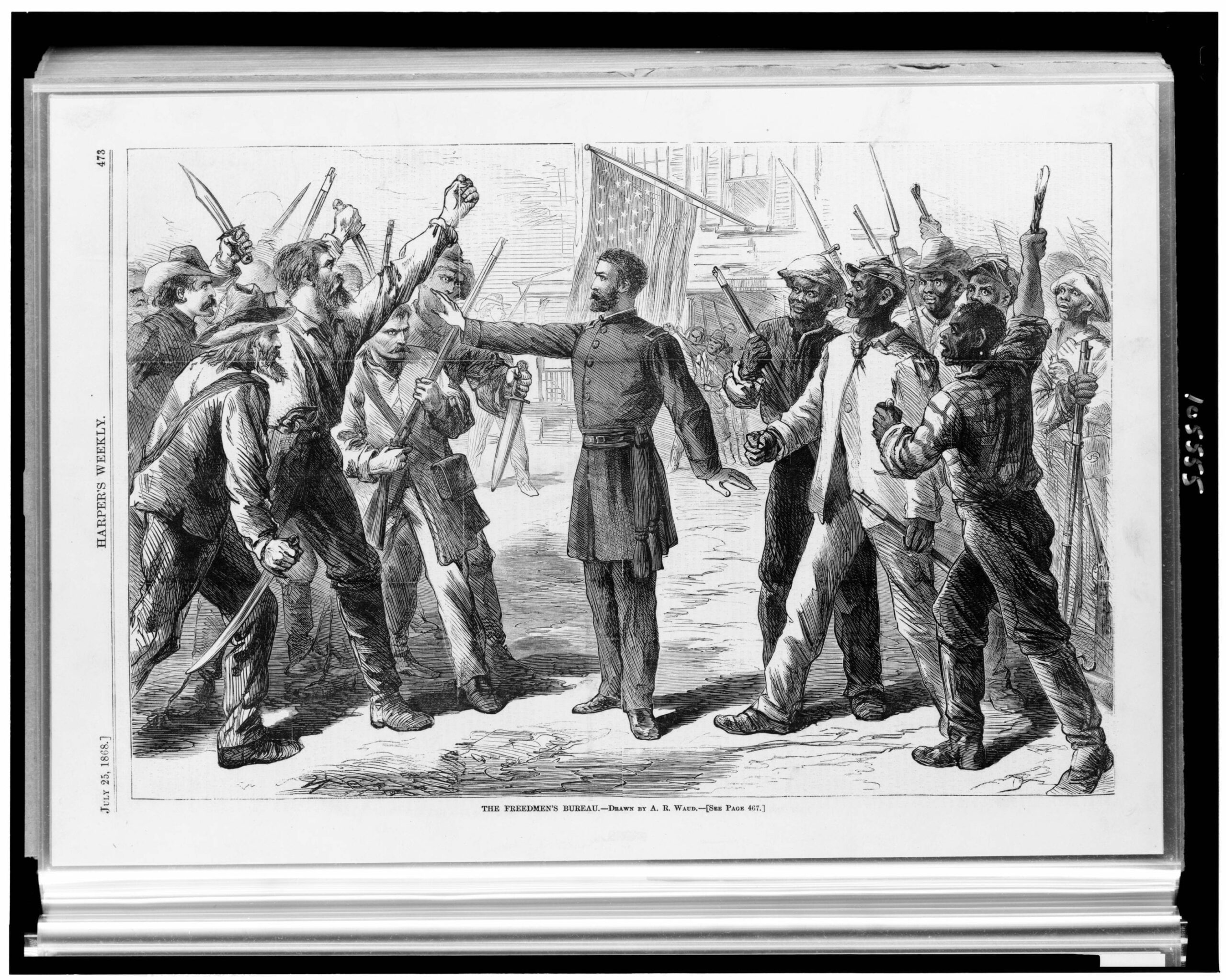

I take up my [second] question. . . . What [is it] that the public safety and the public faith demand? Is there a man here who doubts? In the progress of this war, we found it necessary to proclaim the emancipation of every slave. [Applause.] . . . I would undertake to maintain . . . the proposition that we have to-day an adequate military occupation of the whole rebel country, sufficient to effect the emancipation of every slave, by admitted laws of war. . . .

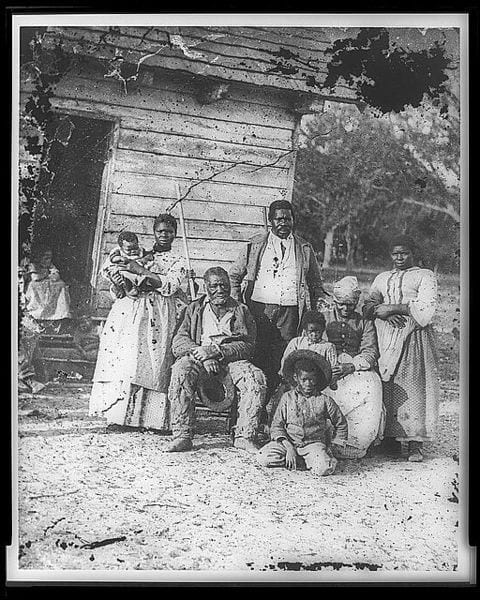

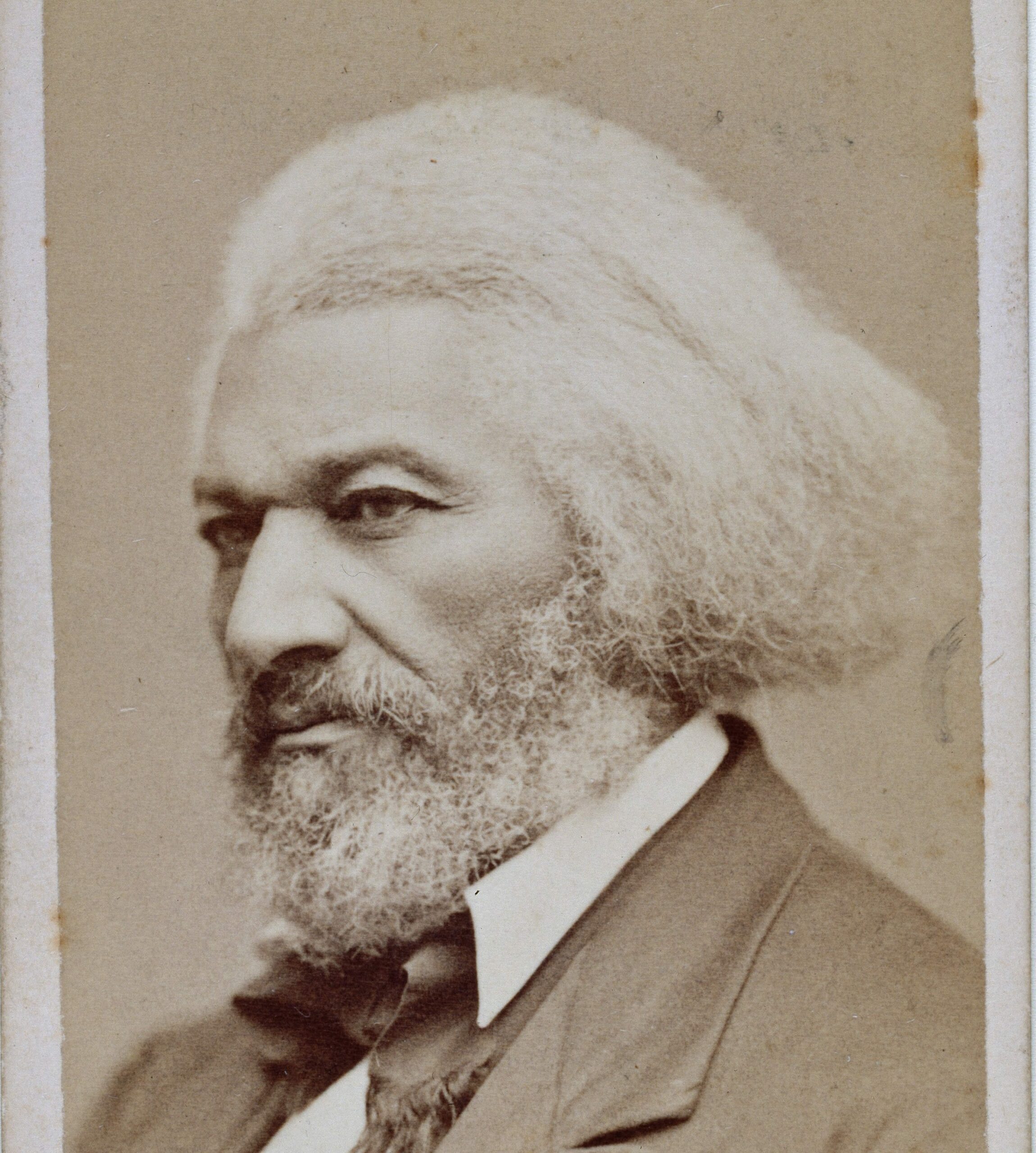

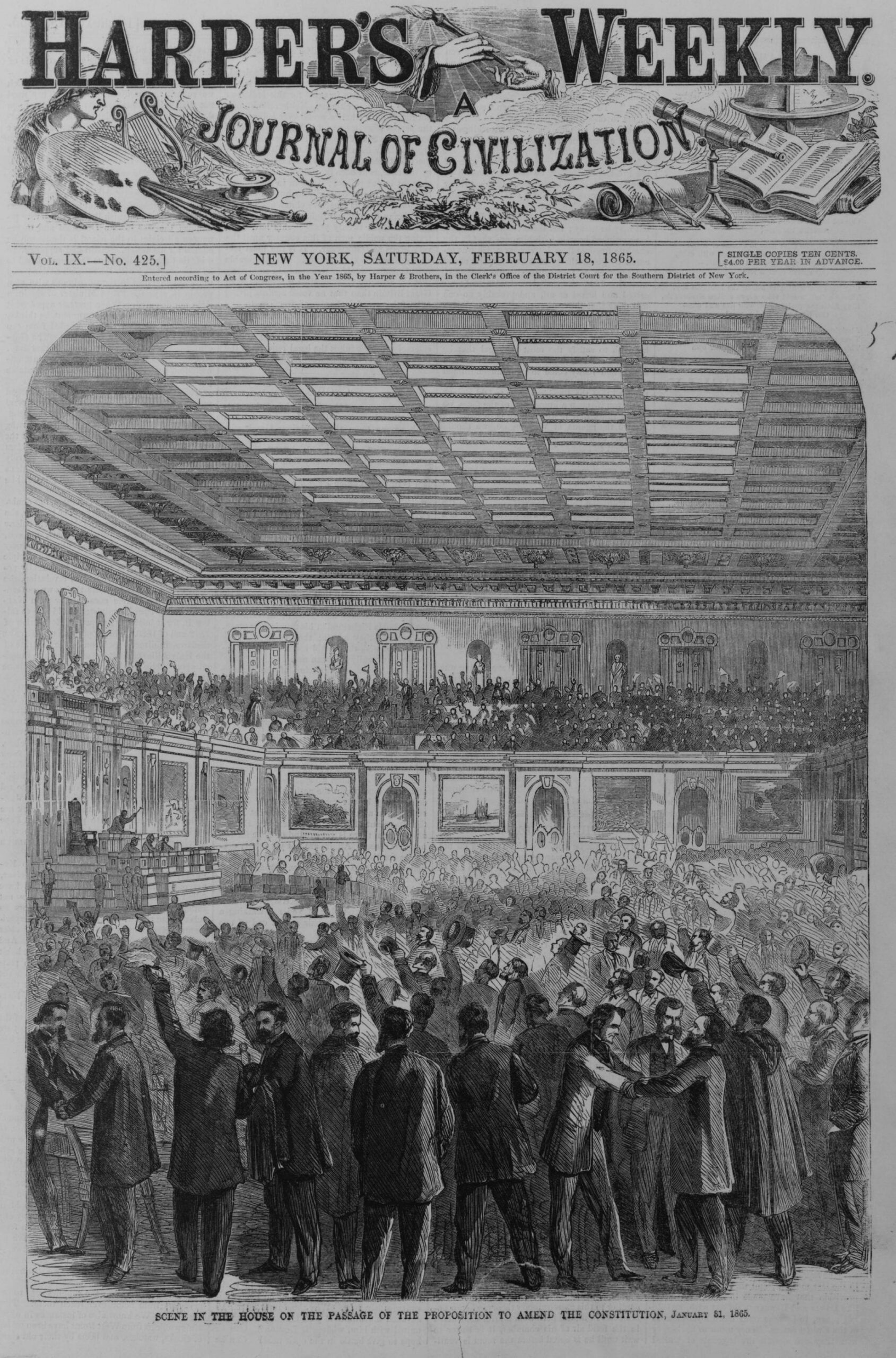

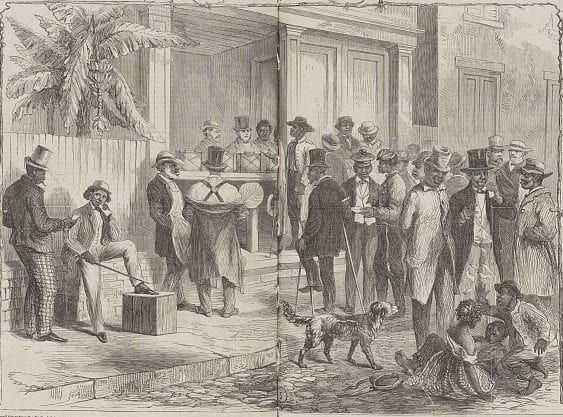

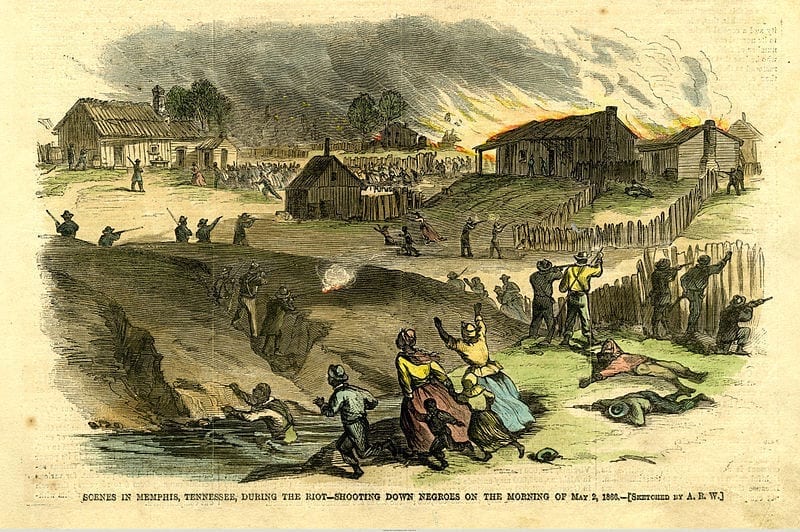

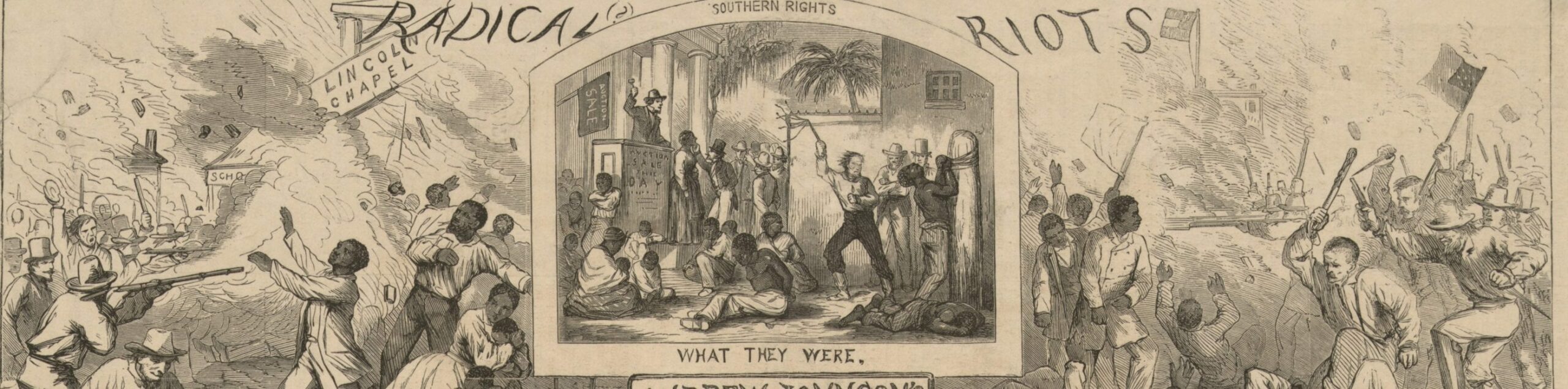

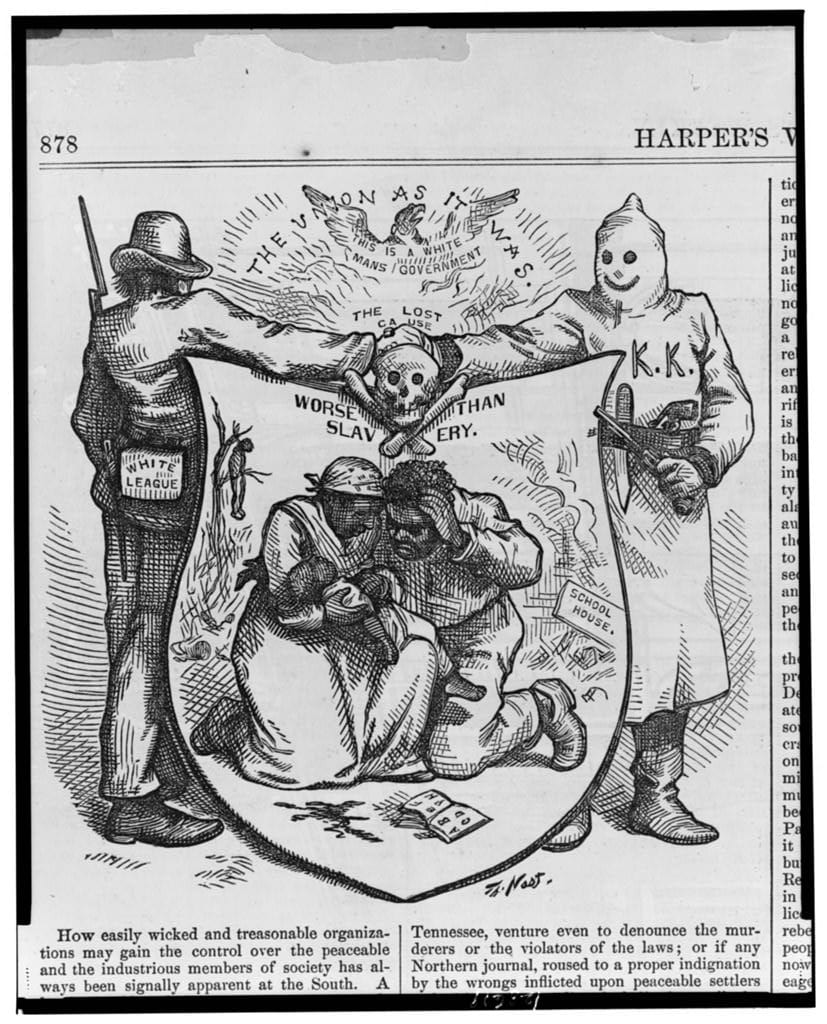

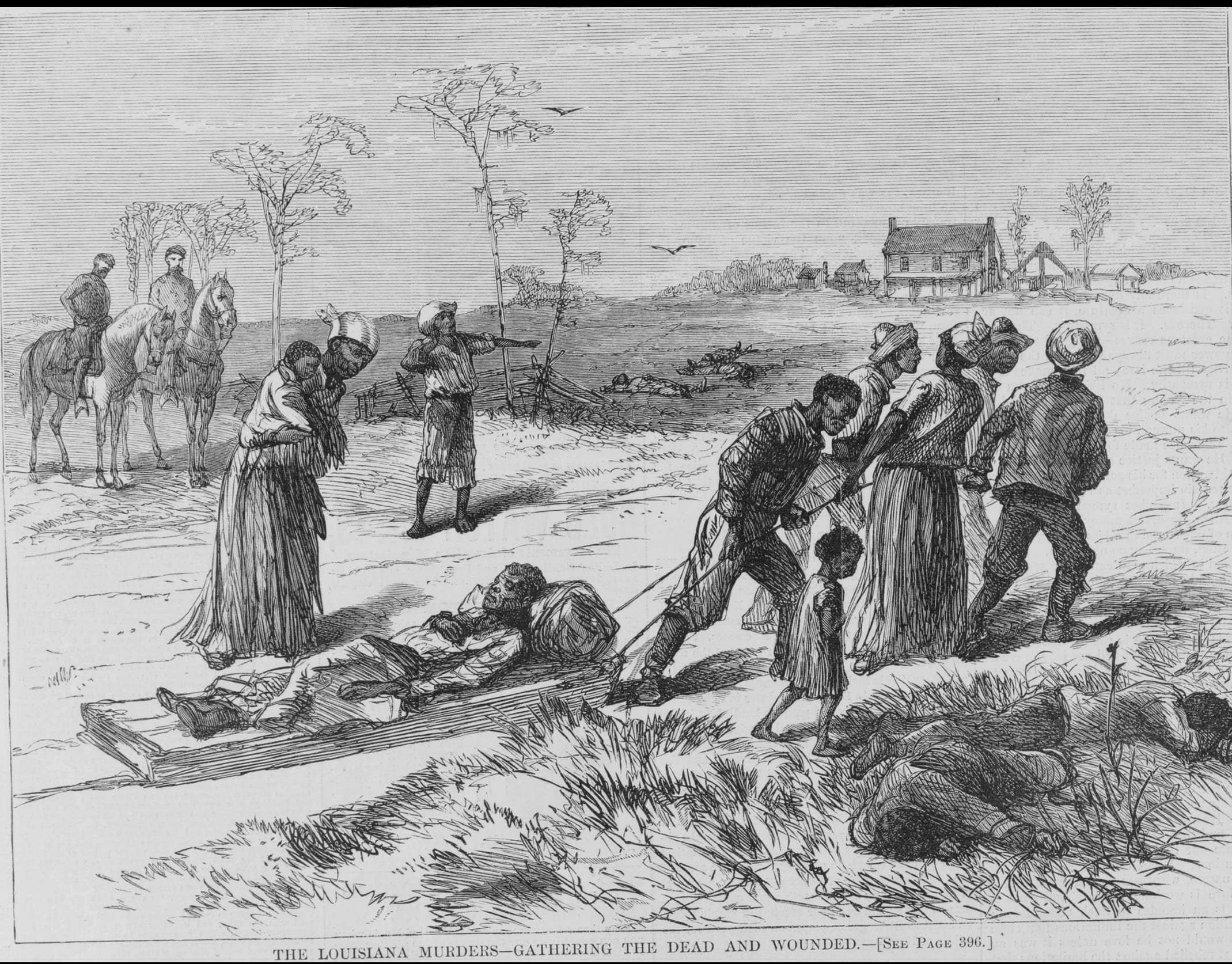

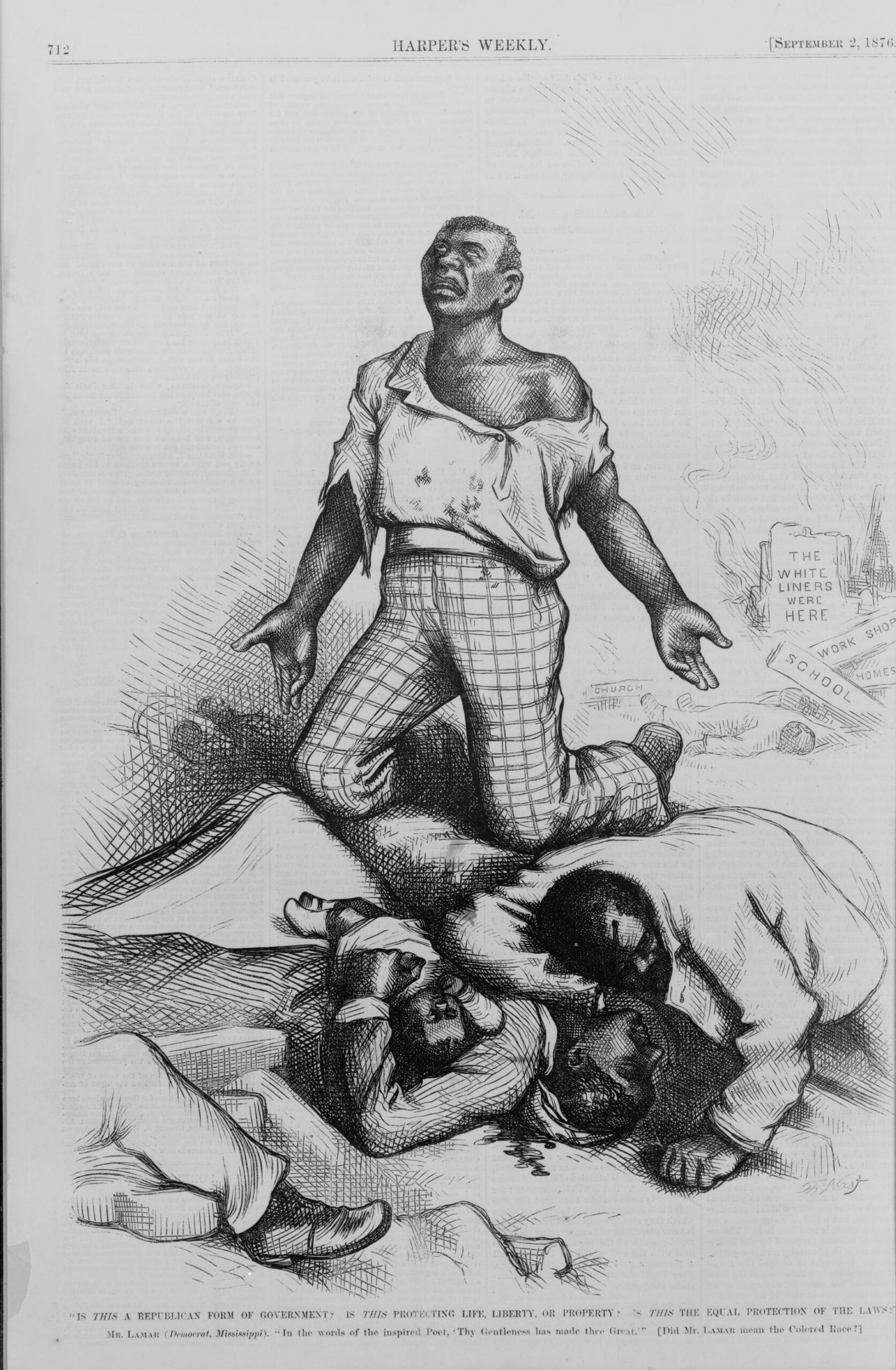

The slaves are emancipated. In form, this is true. But the public faith stands pledged to them, that they and their posterity forever shall have a complete and perfect freedom. [Prolonged applause.] . . . . Then, how shall we secure to them a complete and perfect freedom? The constitution of every slave state is cemented in slavery. Their statute-books are full of slavery. It is the corner-stone of every rebel state. If you allow them to come back at once, without condition, into the exercise of all their state functions, what guaranty have you for the complete freedom of the men you emancipate? There must, therefore, not merely be an emancipation of the actual, living slaves, but there must be an abolition of the slave system. [Applause.] . . .

But, my fellow citizens, is that enough? . . .

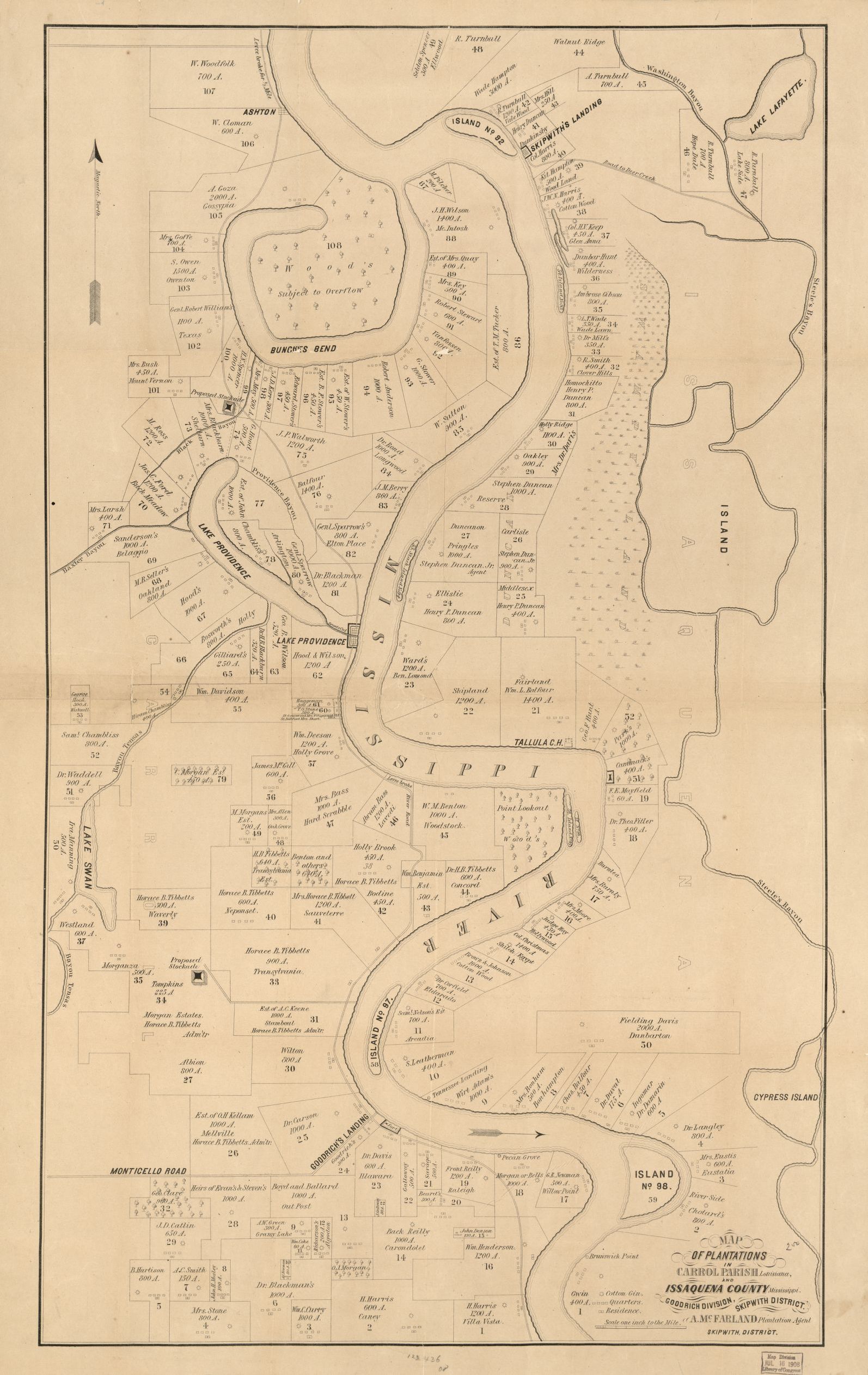

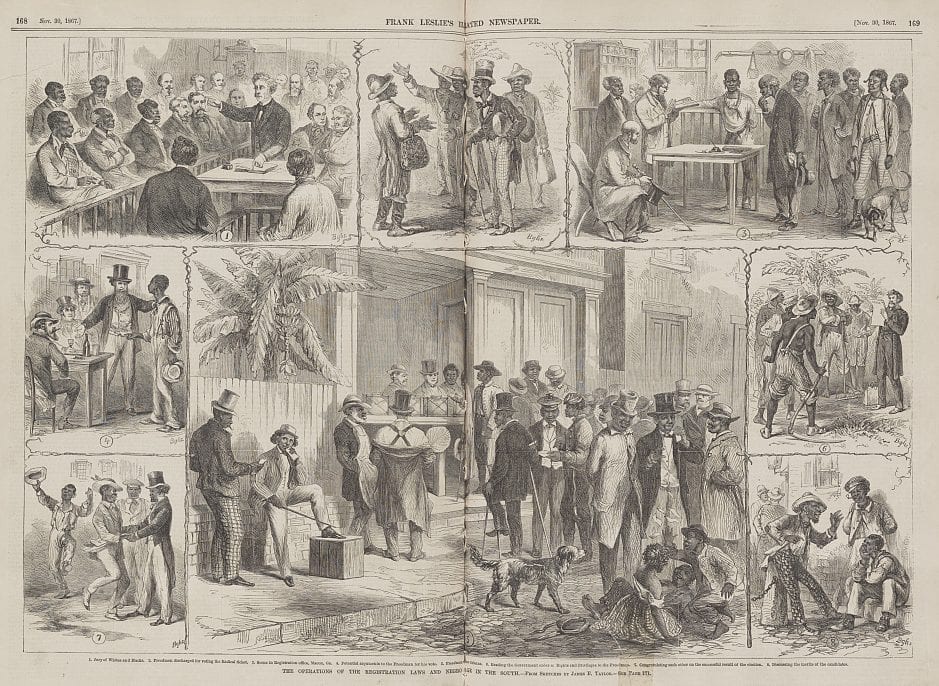

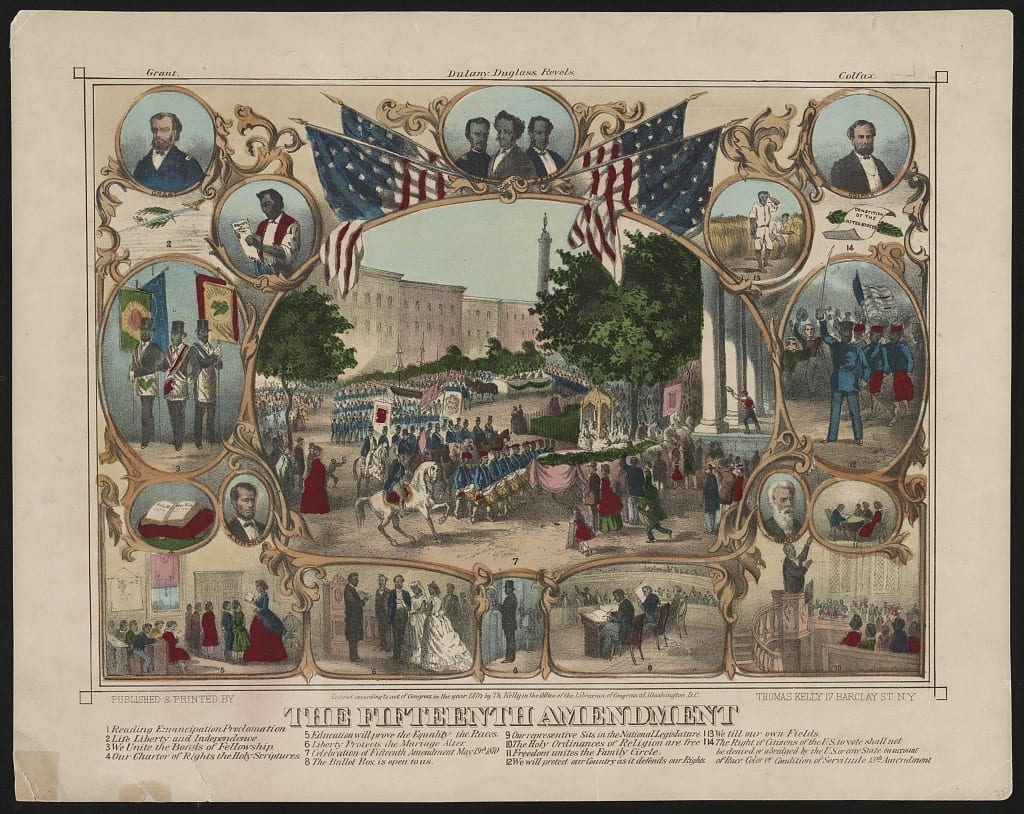

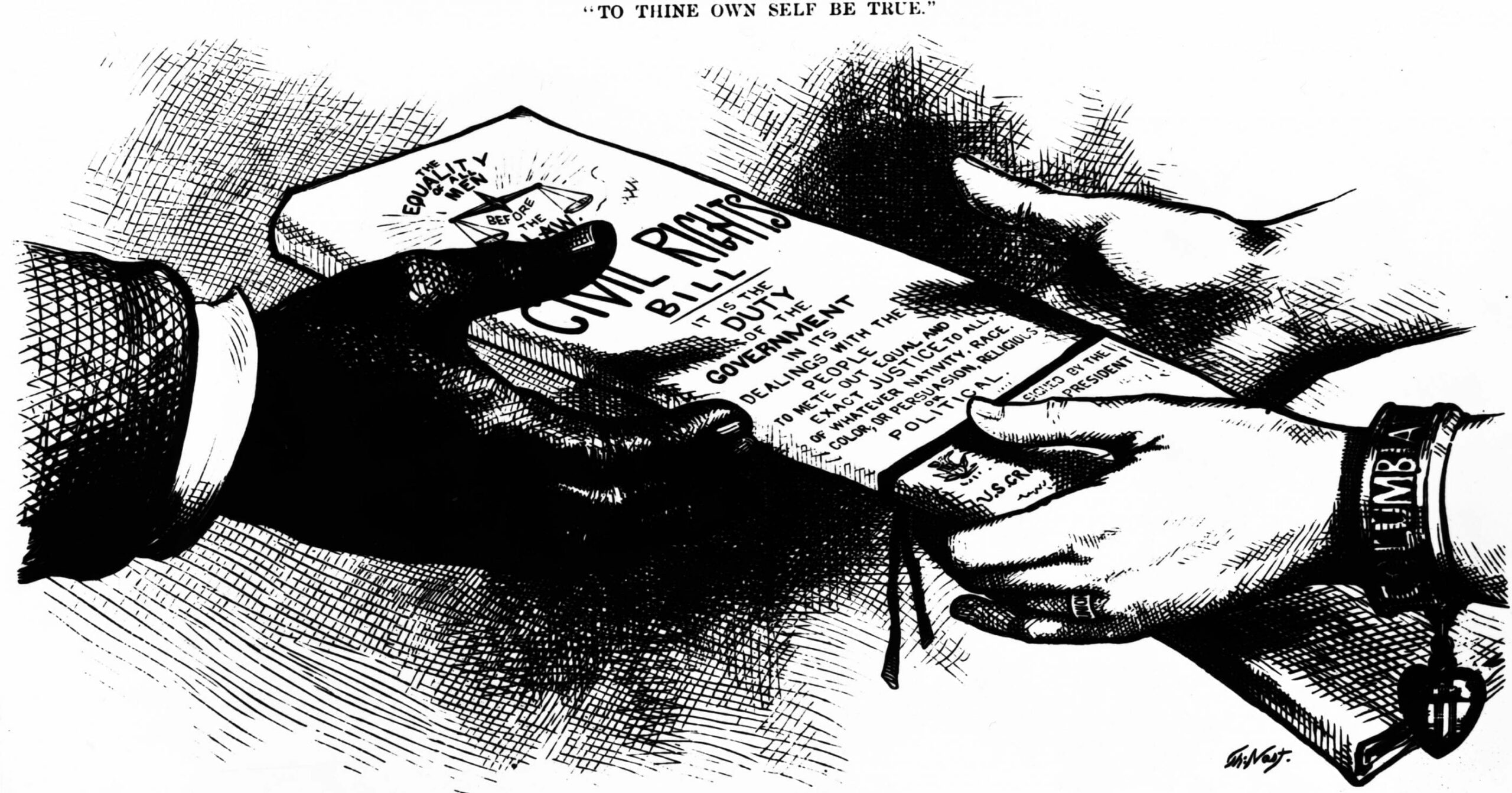

We have a right to require, my friends, that the freedmen of the South shall have the right to hold land. [Applause.] . . . We have a right to require that they shall be allowed to testify in the state courts. [Applause.] . . . We have a right to demand that they shall bear arms as soldiers in the militia. [Applause.] . . . We have a right to demand that there shall be an impartial ballot. [Great applause.] . . .

Now, my friends, let us be frank with one another. On what ground are we going to put our demand for the ballot for freedmen? . . . [Dana notes that in the South, Confederates who do not take the loyalty oath are not to be allowed to vote; while in the North, women are not allowed to vote.] There is no such doctrine as that every human being has a right to vote. Society must settle the right to a vote upon this principle – “The greatest good of the greatest number” must decide it. The greatest good of society must decide it. On what ground, then, do we put it? We put it upon the ground that the public safety and the public faith require that there shall be no distinction of color. [Applause.] . . .

Now comes my third question – How do you propose to accomplish it? . . .

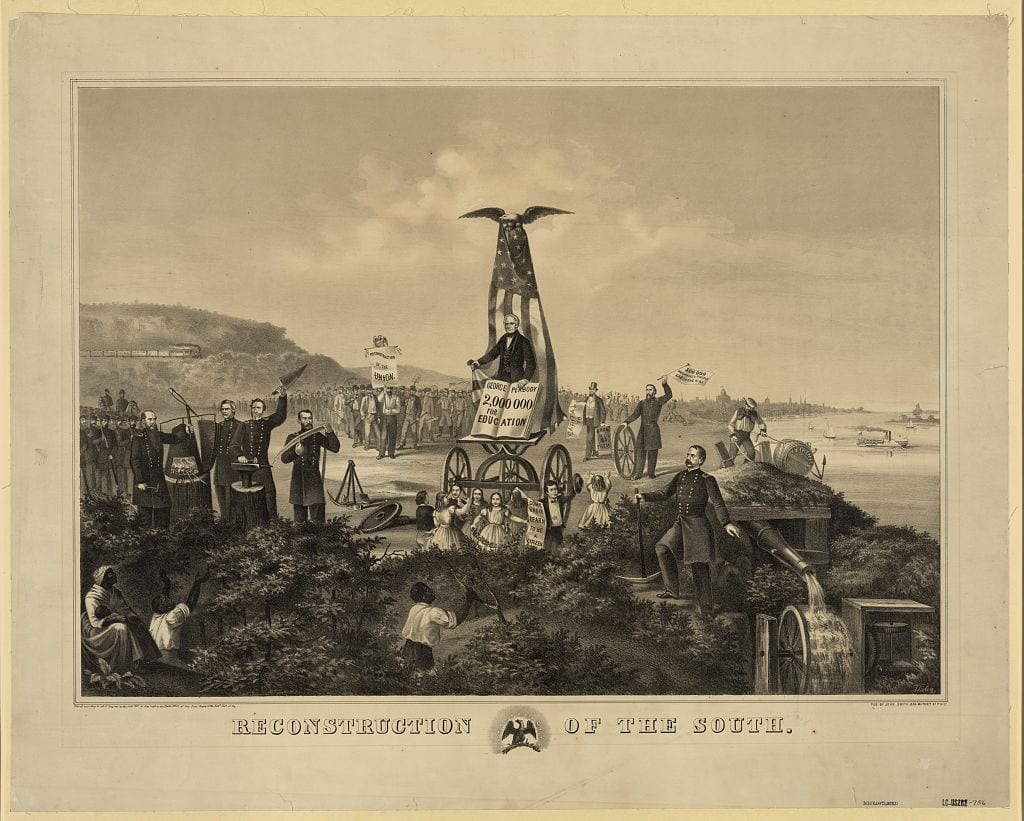

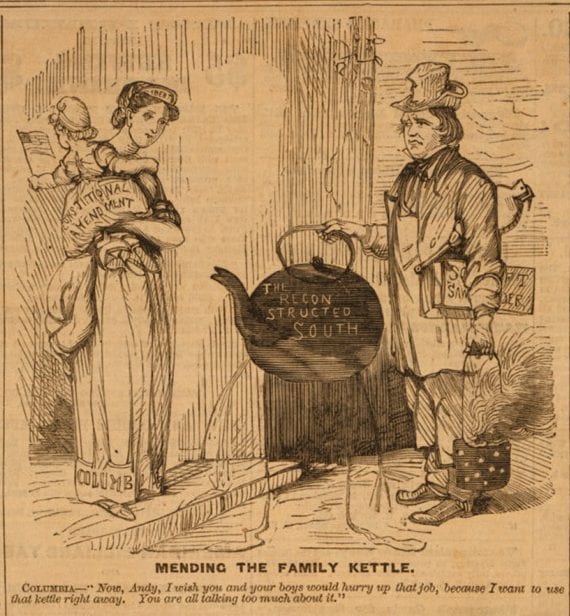

You find the answer in my first proposition. . . . We hold each state in the grasp of war until the state does what we have a right to require of her. [Applause.] . . . We have a military occupation. . . .

I ask, again, how shall we obtain what we have a right to acquire? The changes we require are changes of their constitutions, are they not? The changes must be fundamental. The people are remitted to their original powers. They must meet in conventions and form constitutions, and those constitutions must be satisfactory to the republic. [Loud applause.] . . .

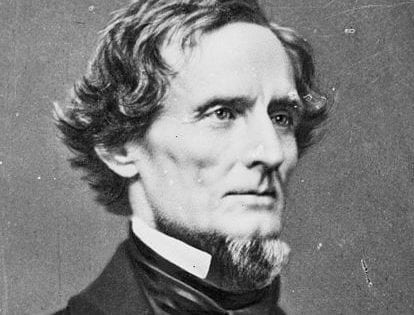

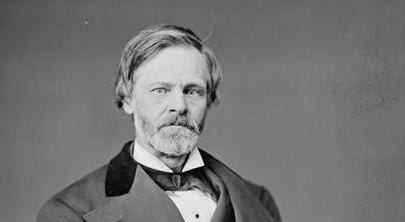

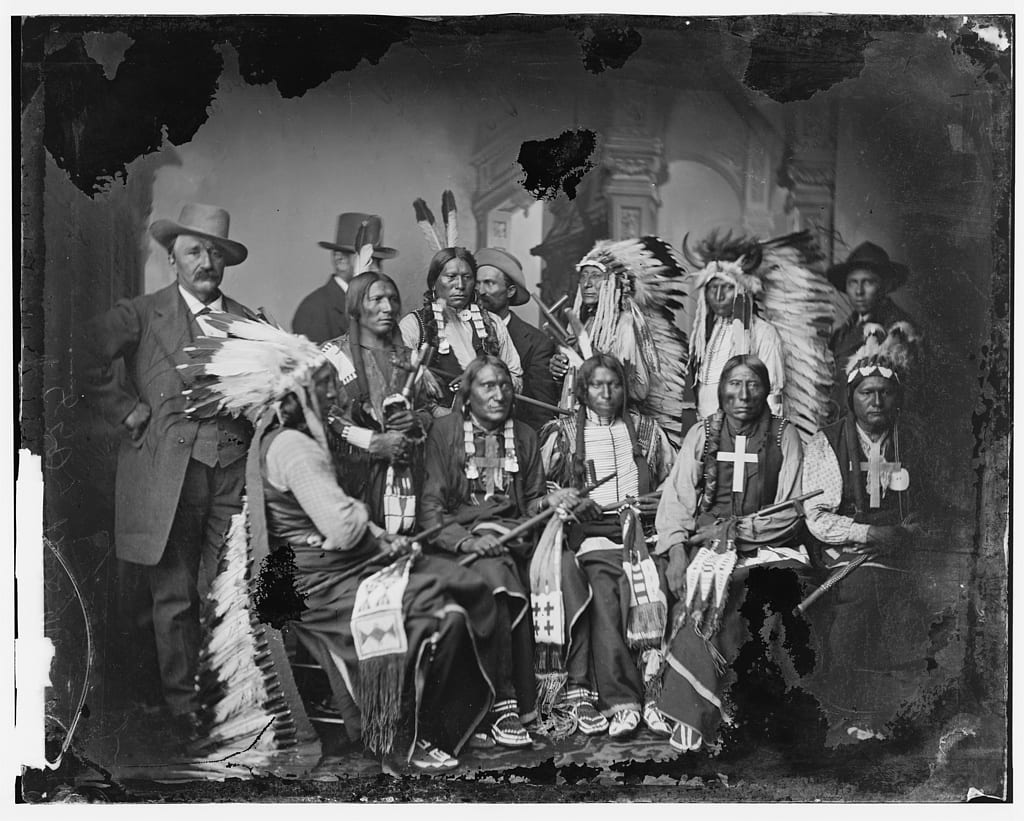

. . . Suppose the states do not do what we require – what then? . . . Suppose President Johnson’s experiment in North Carolina and Mississippi fails, and the white men are determined to keep the black men down – what then? Mr. President, I hope we shall never be called upon to answer, practically, that question. . . . But if we come to it . . . I, for one, am prepared with an answer. I believe that if you come to the ultimate right of the thing, the ultimate law of the case, it is this: that this war – no not the war, the victory in the war – places, not the person, nor the life, not the private property of the rebels – they are governed by other considerations and rules – I do not speak of them – but the political systems of the rebel states, at the discretion of the republic. [Great applause.] . . . It is the necessary result of conquest, with military occupation, in a war of such dimensions, such a character, and such consequences as this. . . .

When a man accepts a challenge to a duel, what does he put at stake? He puts his life at stake, does he not? And is it not childish, after the fatal shot is fired, to exclaim, “Oh, death and widowhood and orphanage are fearful things!” . . . When a nation allows itself to be at war, or when a people make war, they put at stake their national existence. [Applause.] . . . The conqueror must choose between two courses – to permit the political institutions, the body politic, to go on, and treat with it, or obliterate it. We have destroyed and obliterated their central government. Its existence was treason. As to their states, we mean to adhere to the first course. We mean to say the states shall remain, with new constitutions, new systems. We do not mean to exercise sovereign civil jurisdiction over them in our Congress. Fellow citizens, it is not merely out of tenderness to them; it would be the most dangerous possible course for us. Our system is a planetary system; each planet revolving round its orbit, and all round a common sun. This system is held together by a balance of powers – centripetal and centrifugal forces. We have established a wise balance of forces. Let not that balance be destroyed. If we should undertake to exercise sovereign civil jurisdiction over those states, it would be as great a peril to our system as it would be a hardship upon them. We must not, we will not undertake it, except as the last resort of the thinking and the good – as the ultimate final remedy, when all others have failed. . . .

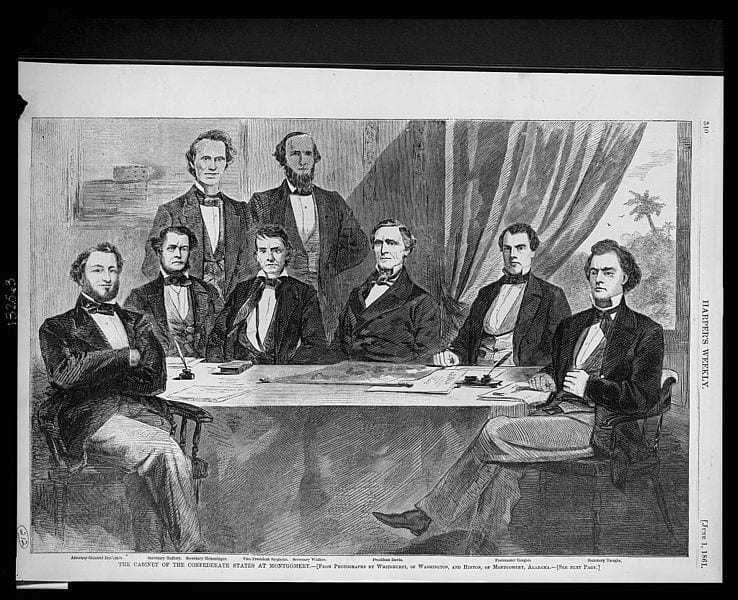

Letter to William Sharkey

August 15, 1865

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.