Introduction

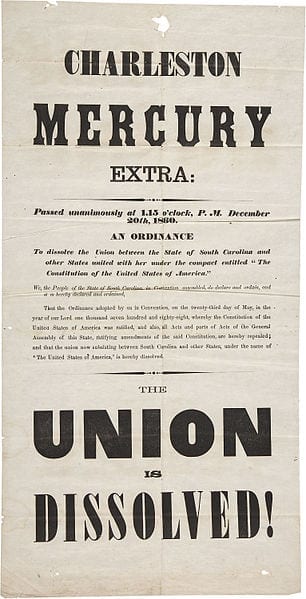

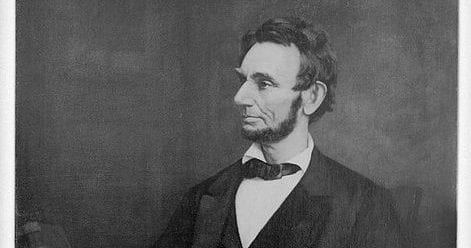

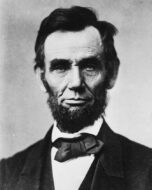

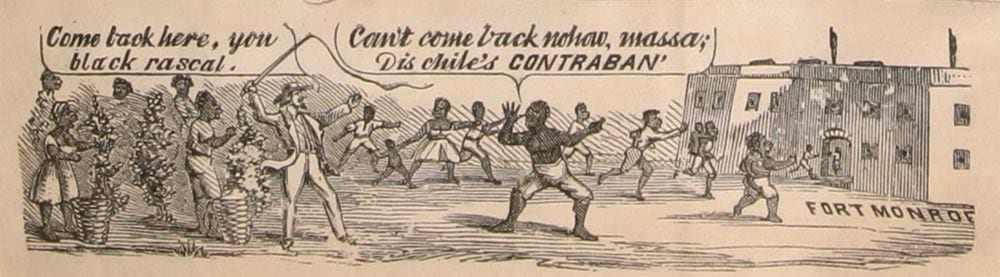

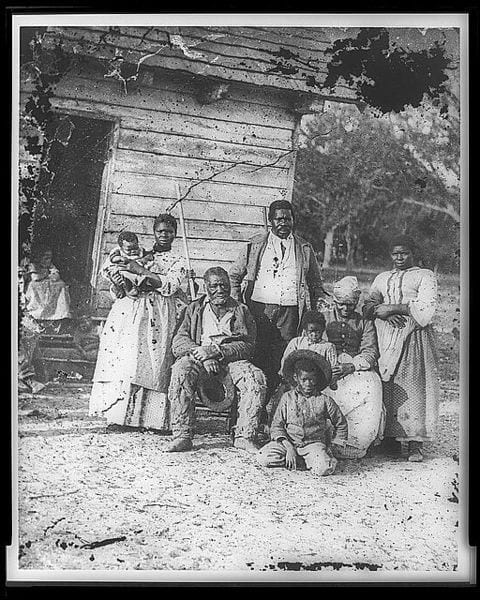

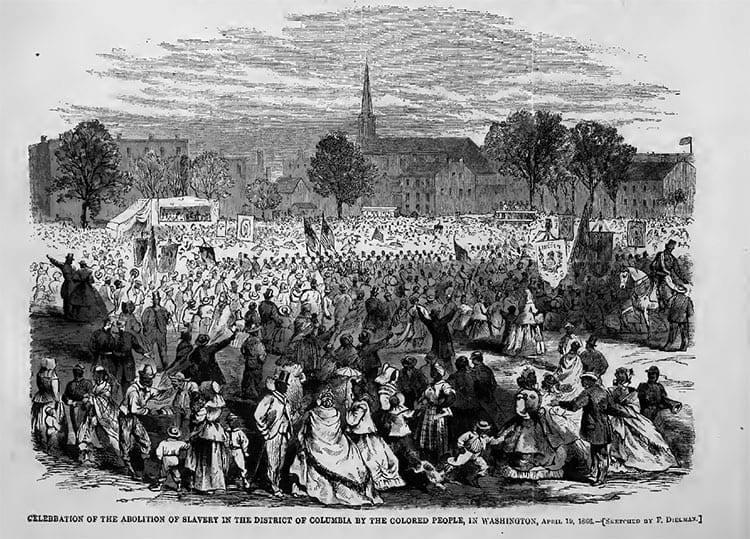

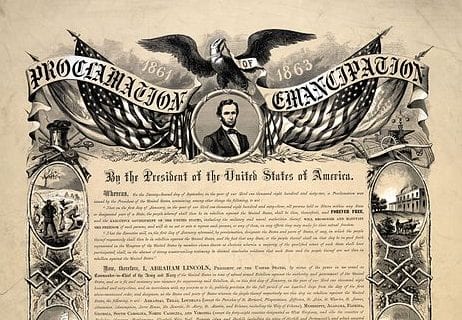

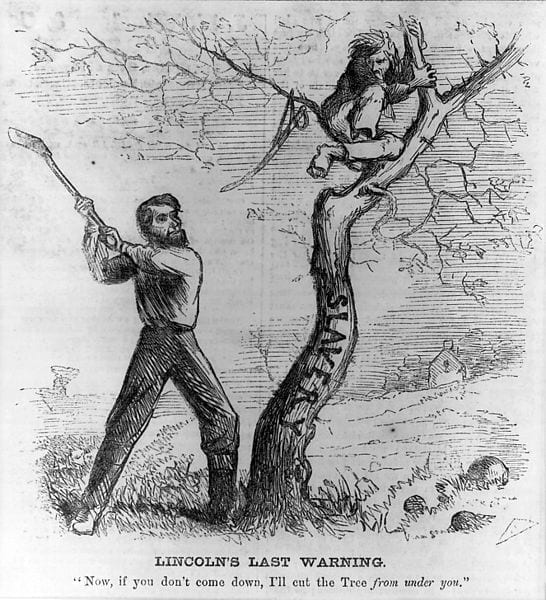

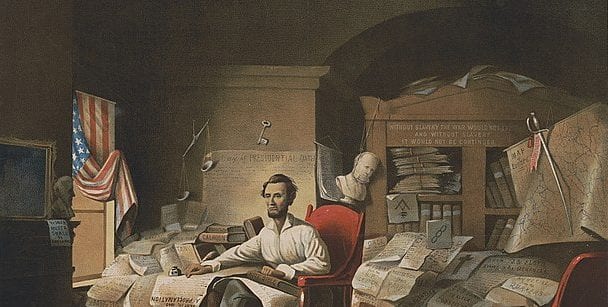

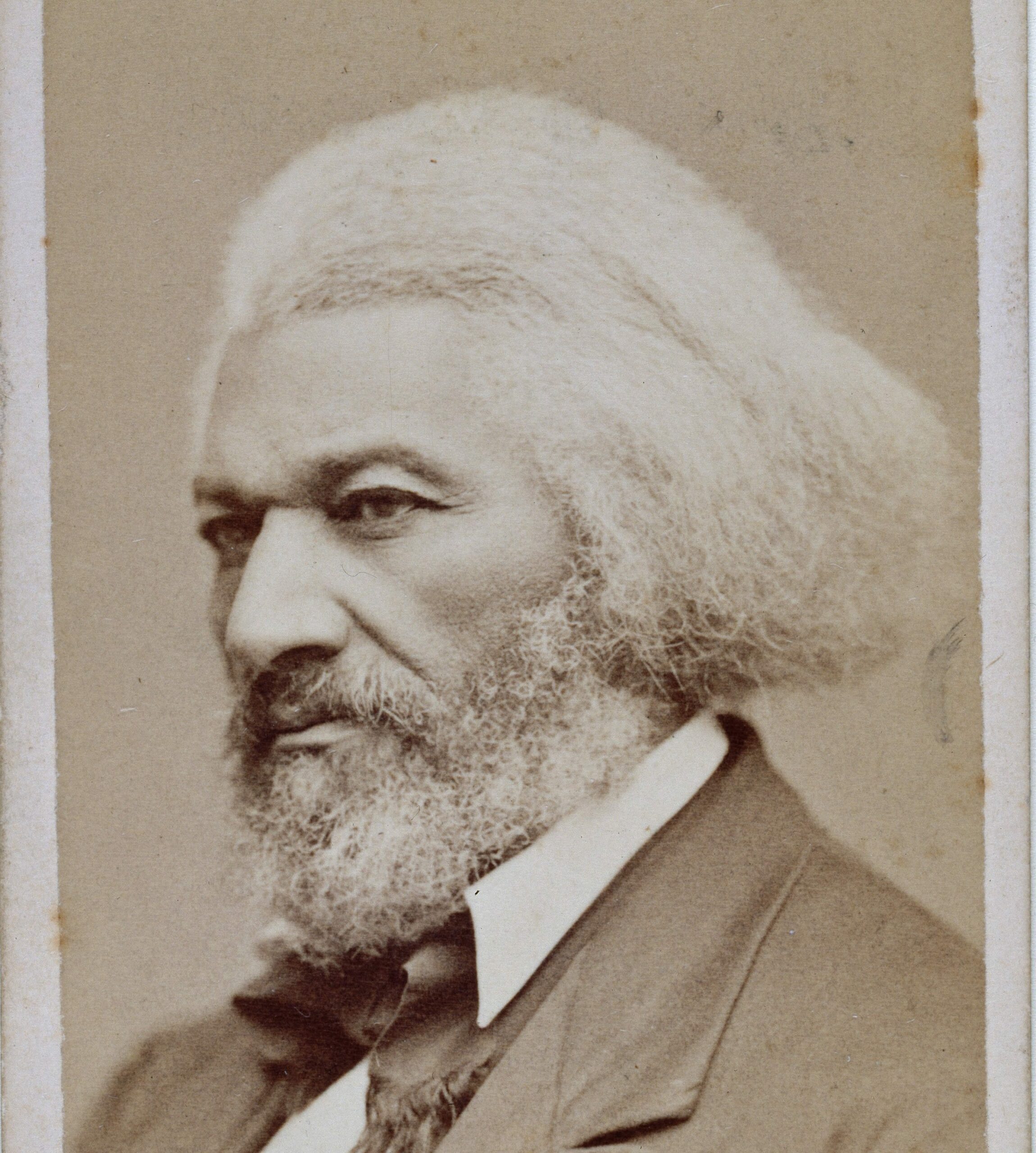

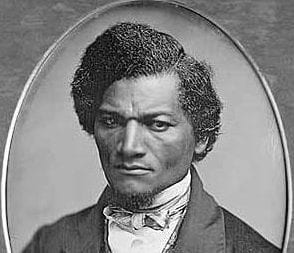

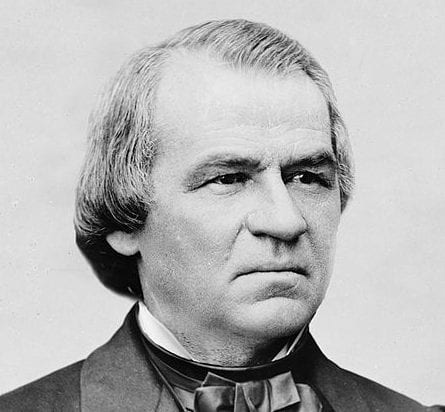

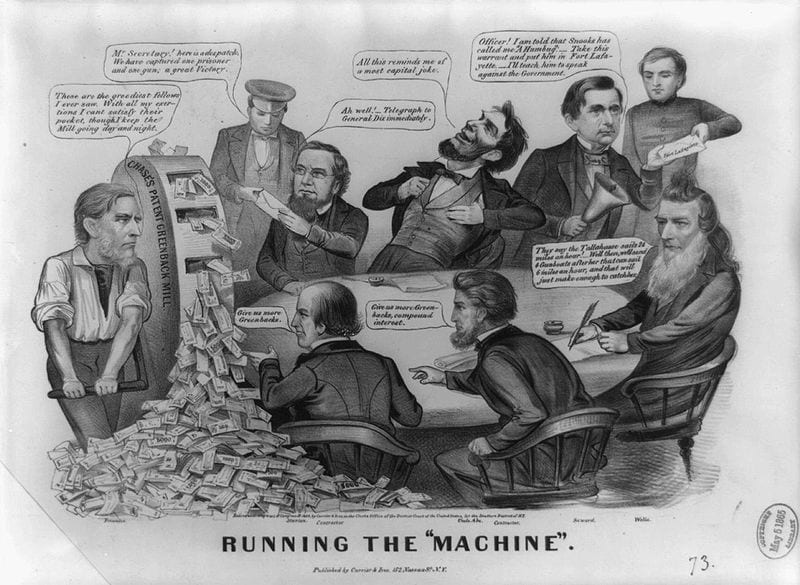

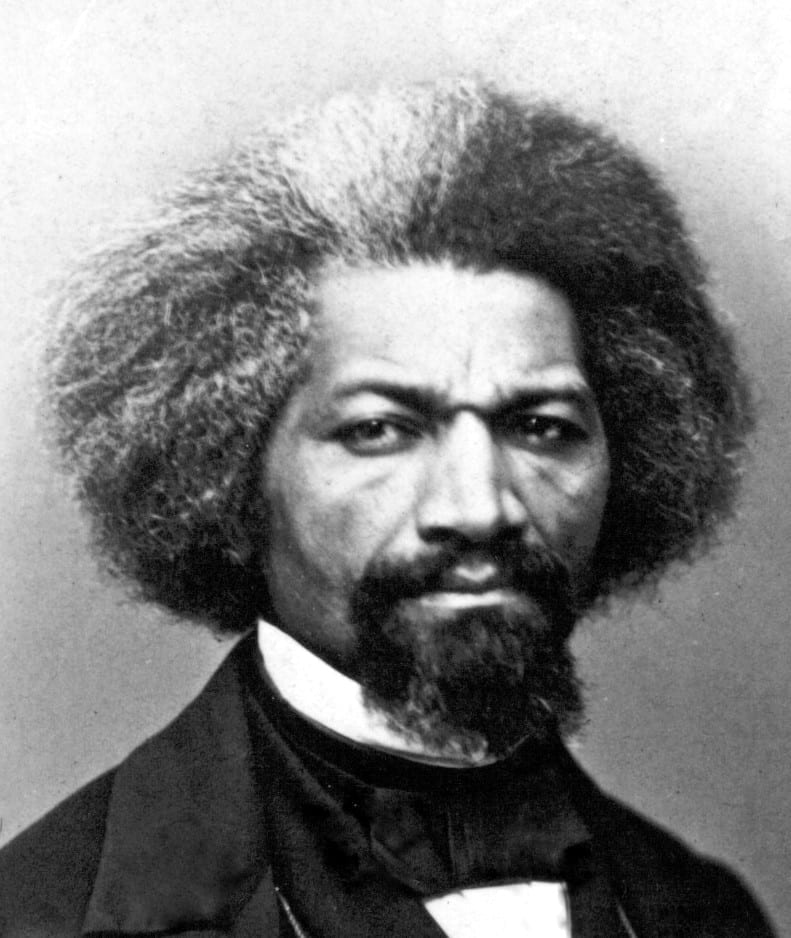

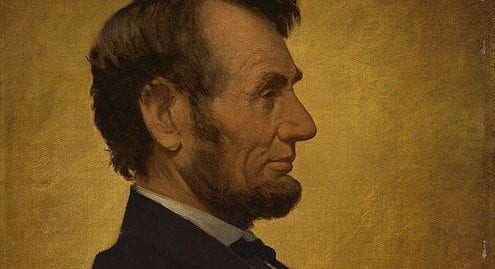

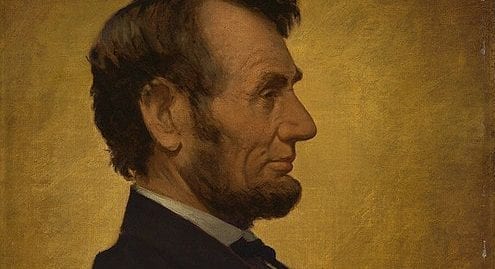

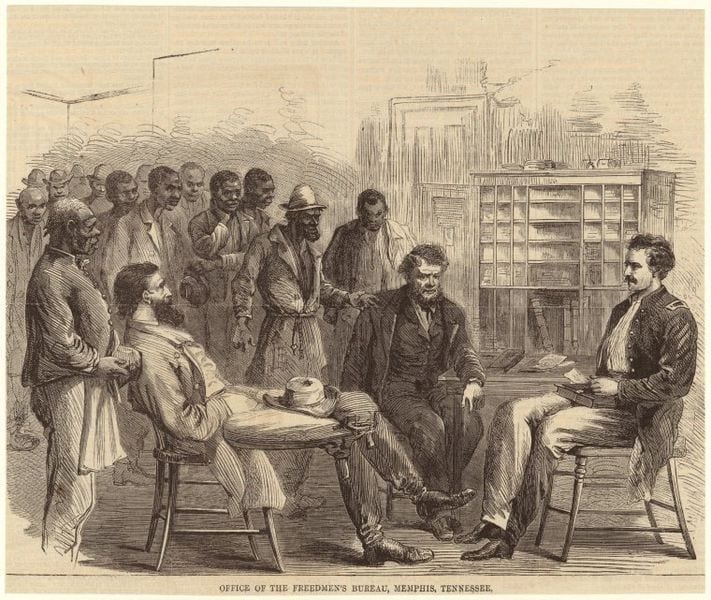

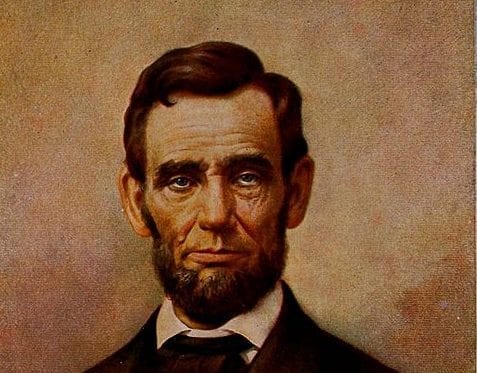

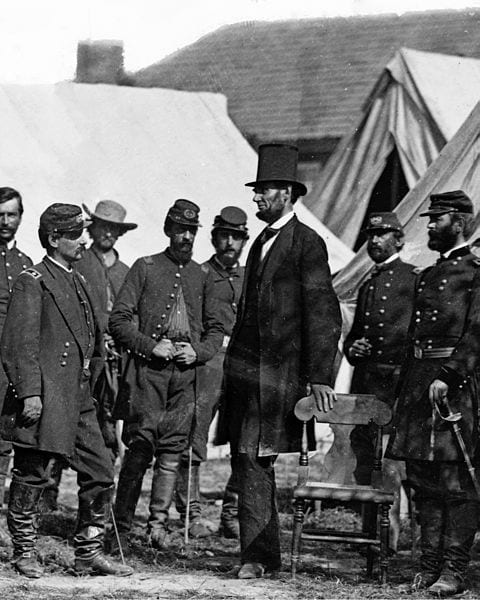

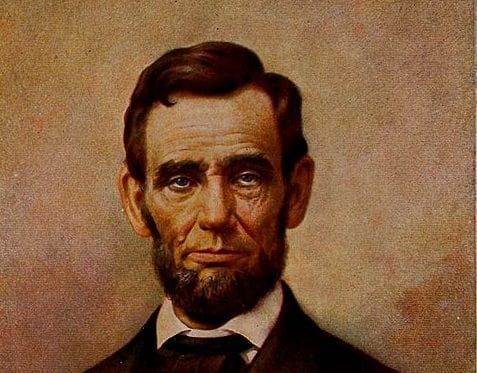

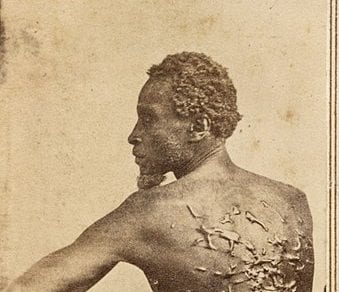

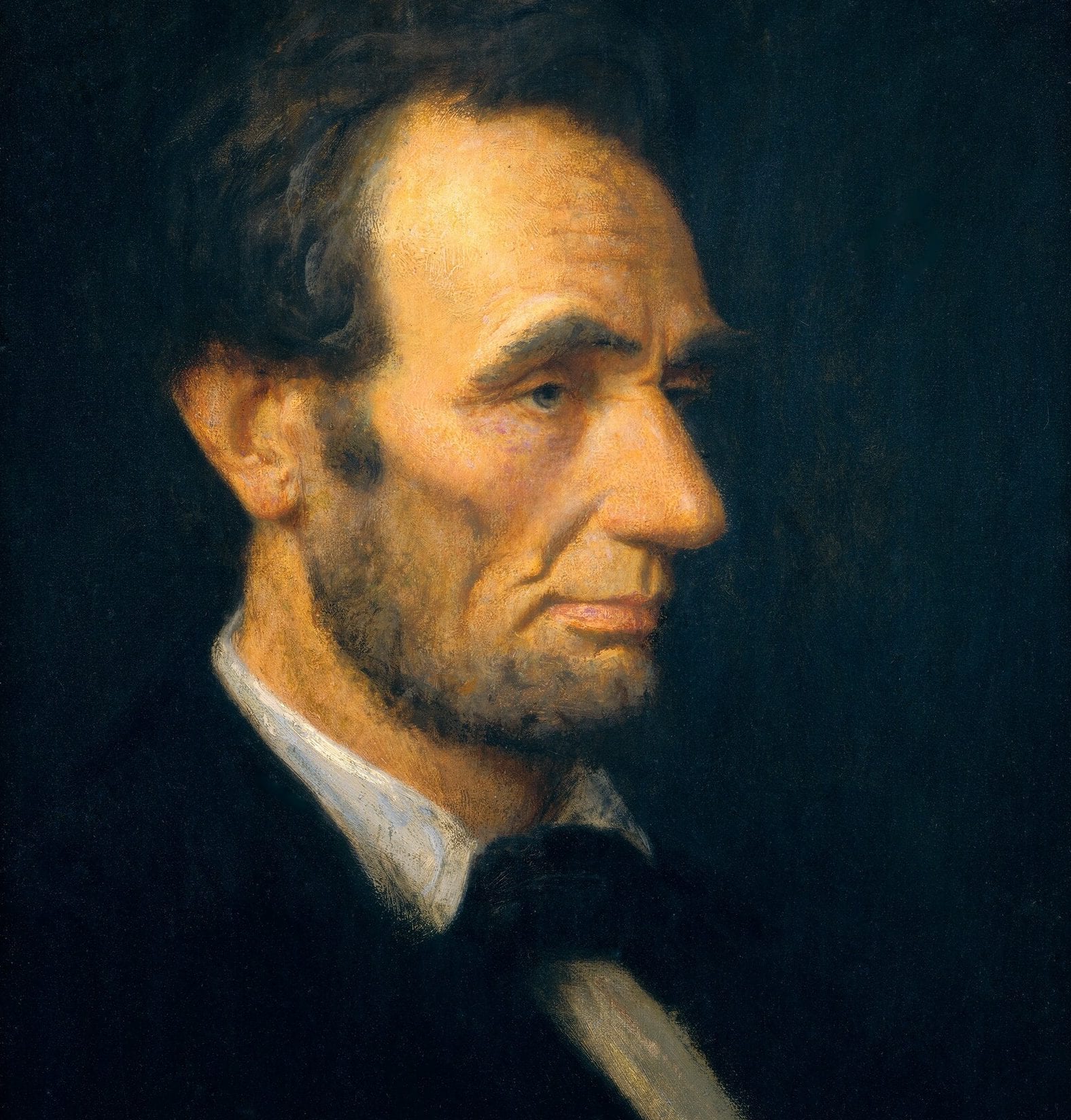

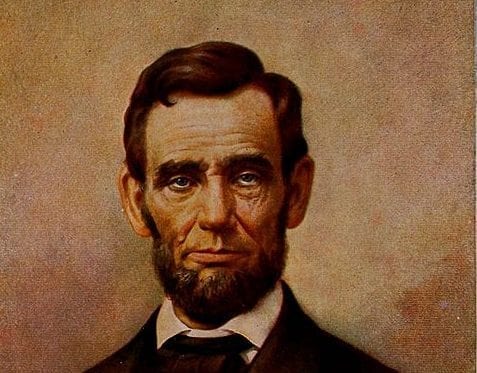

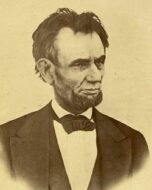

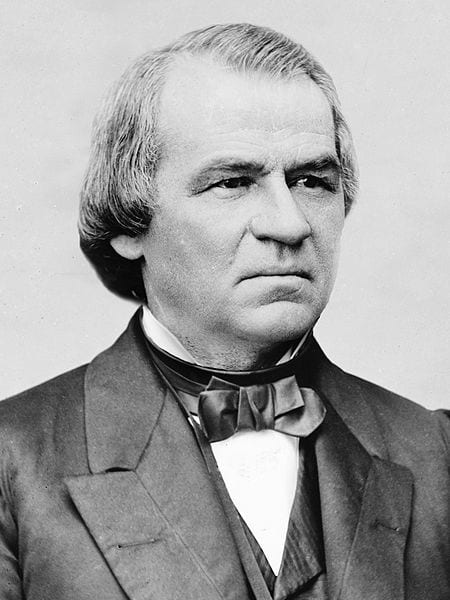

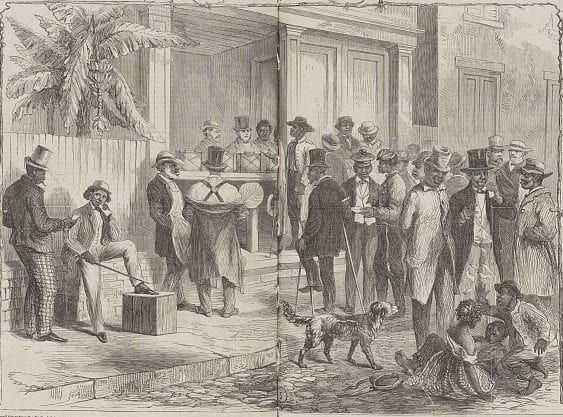

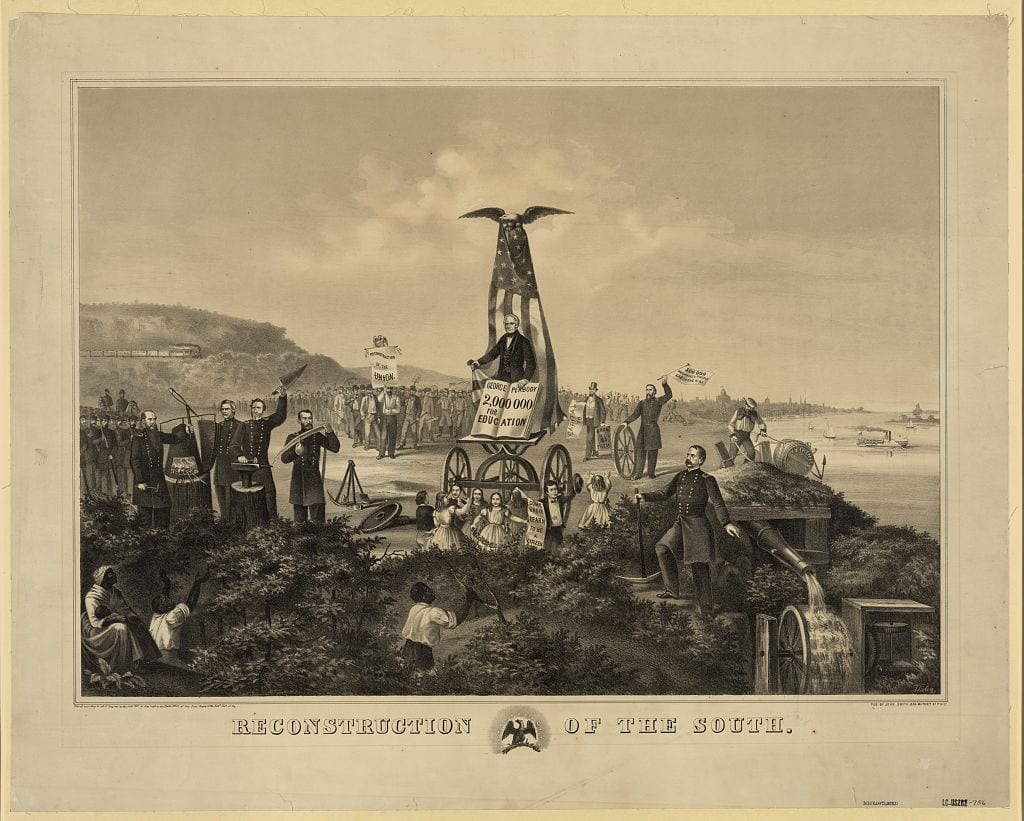

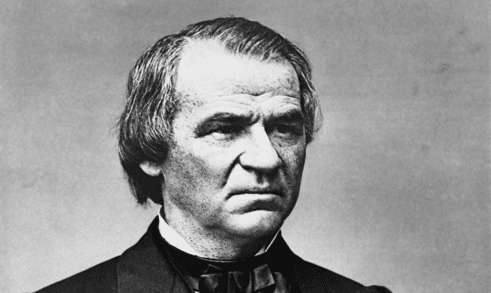

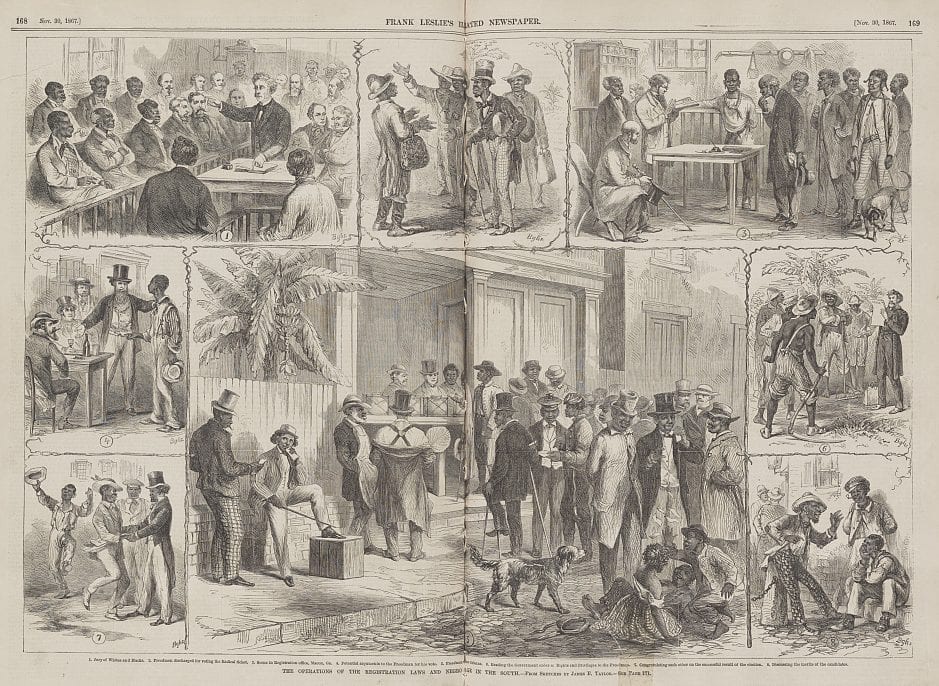

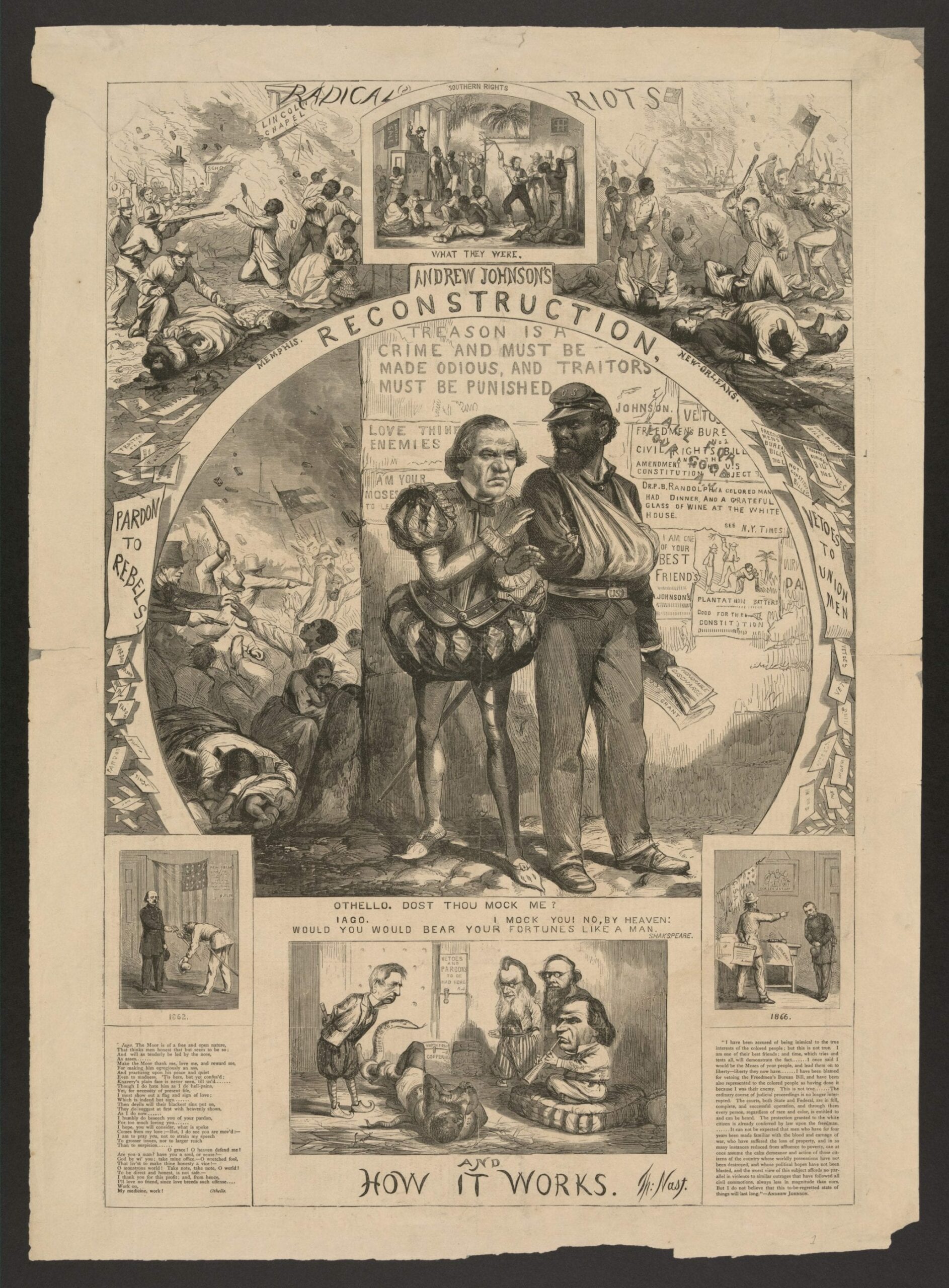

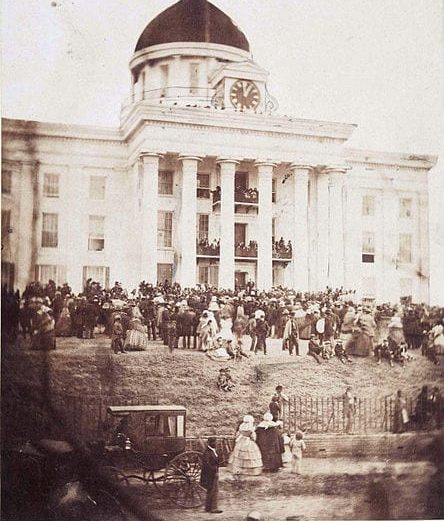

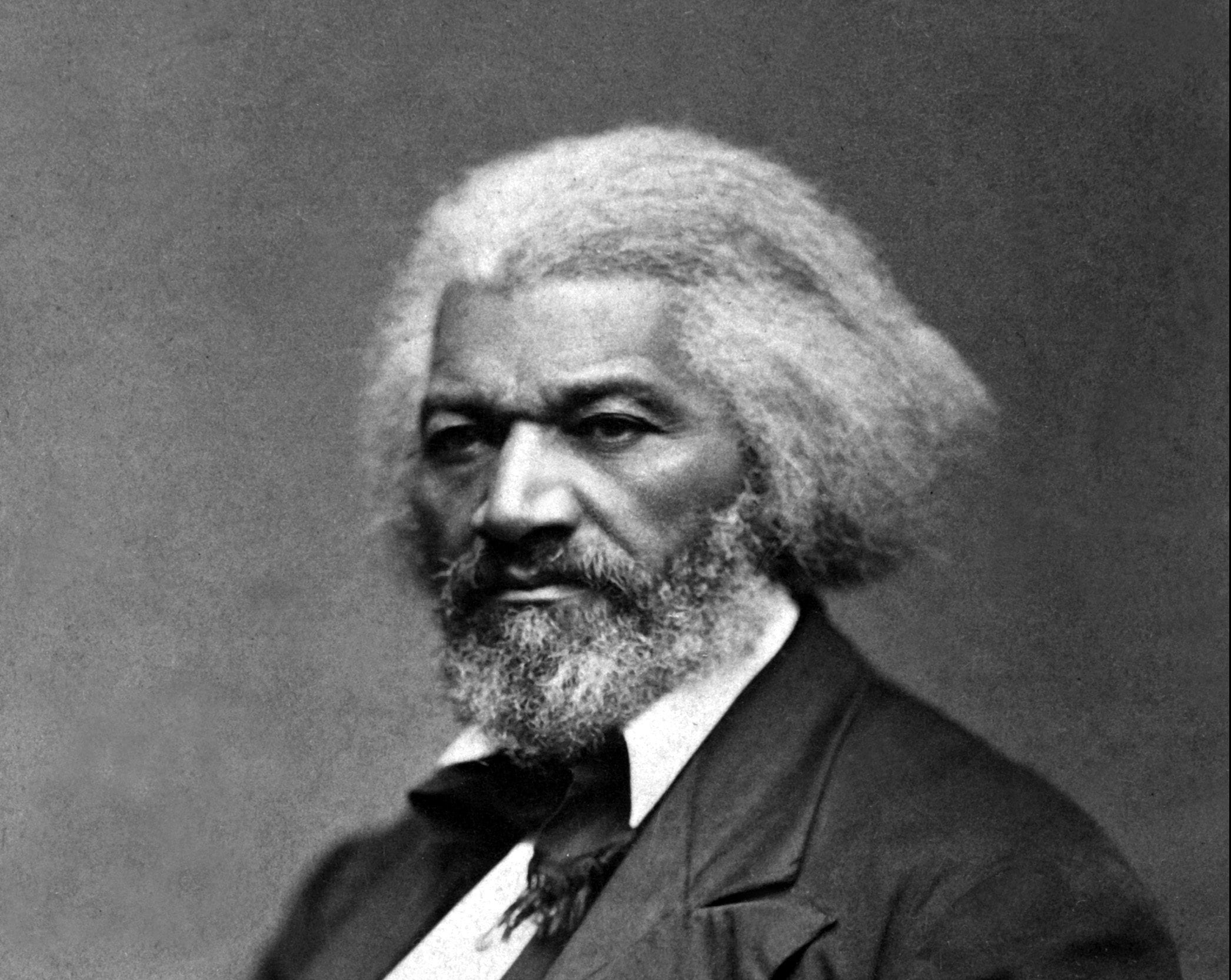

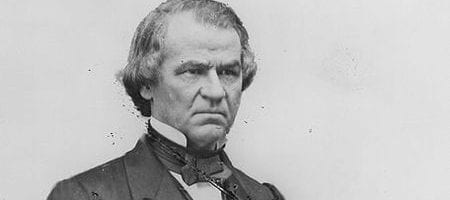

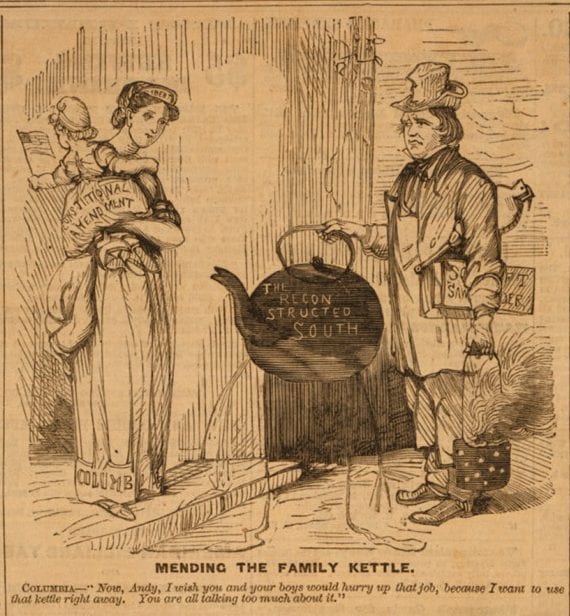

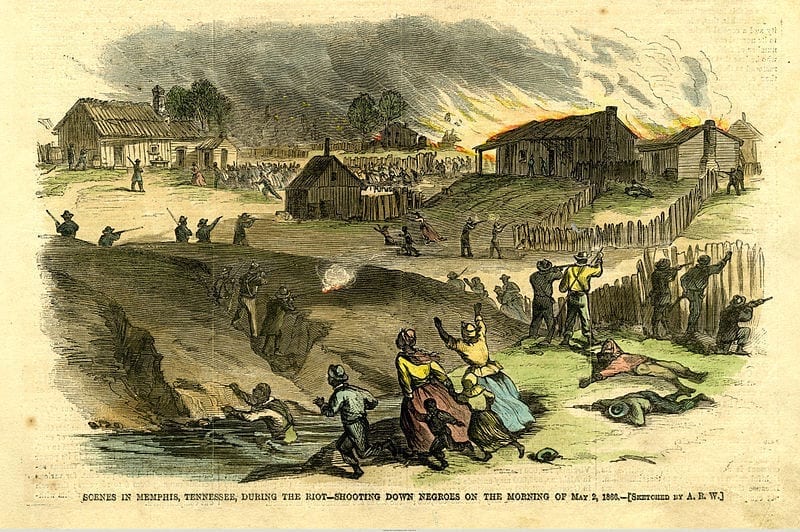

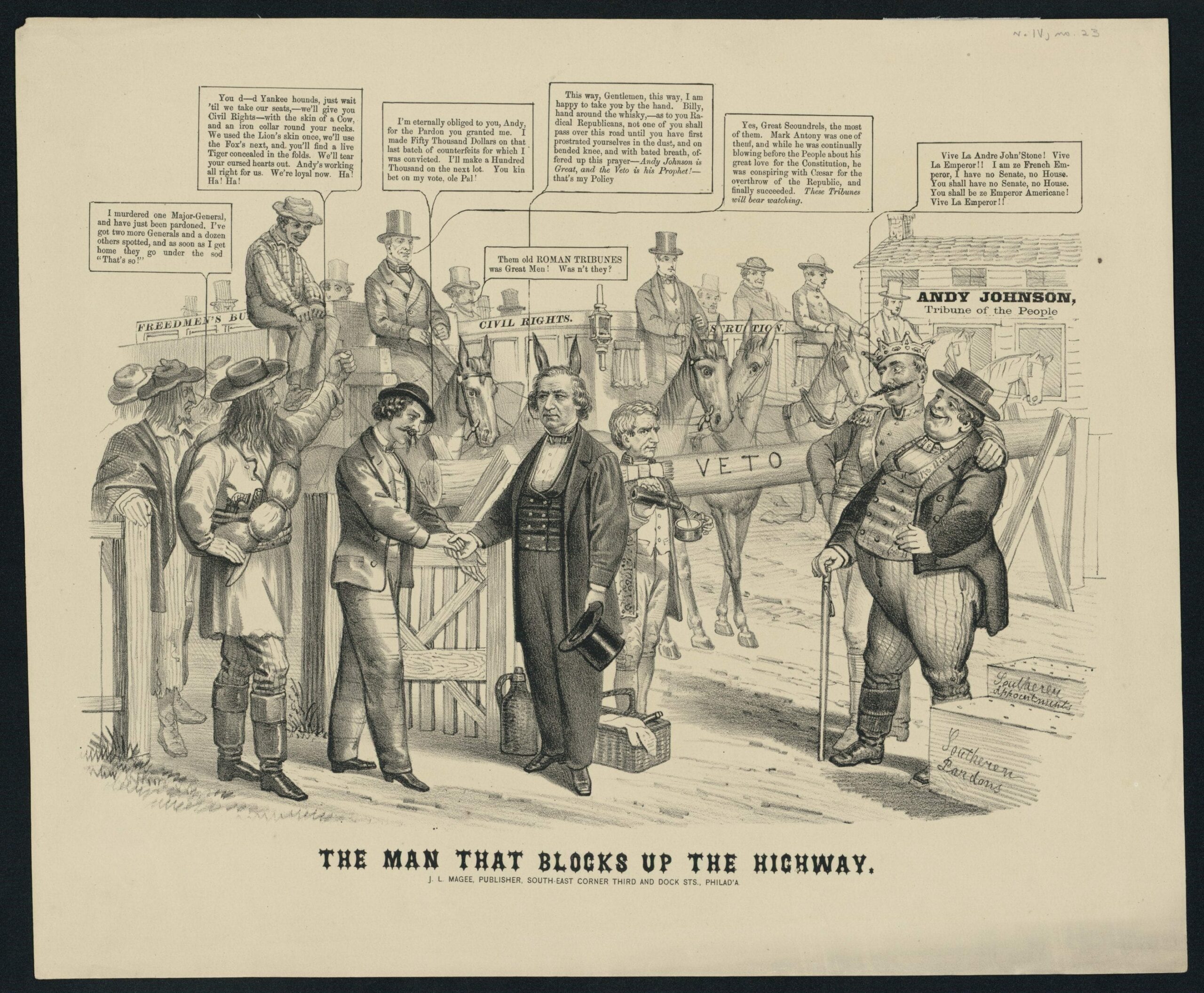

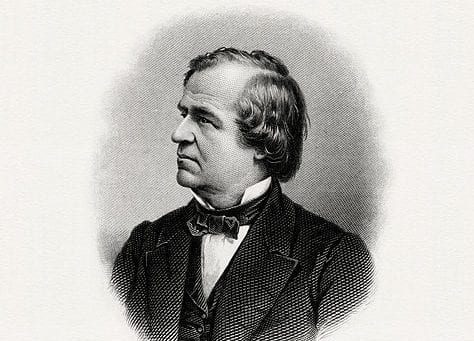

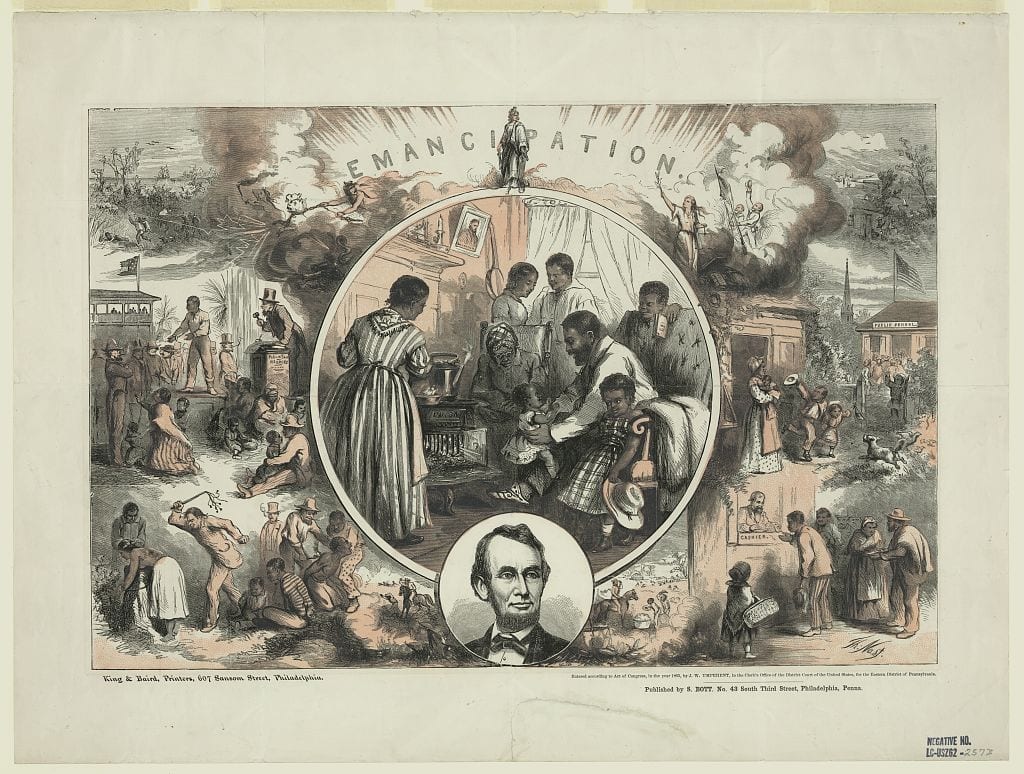

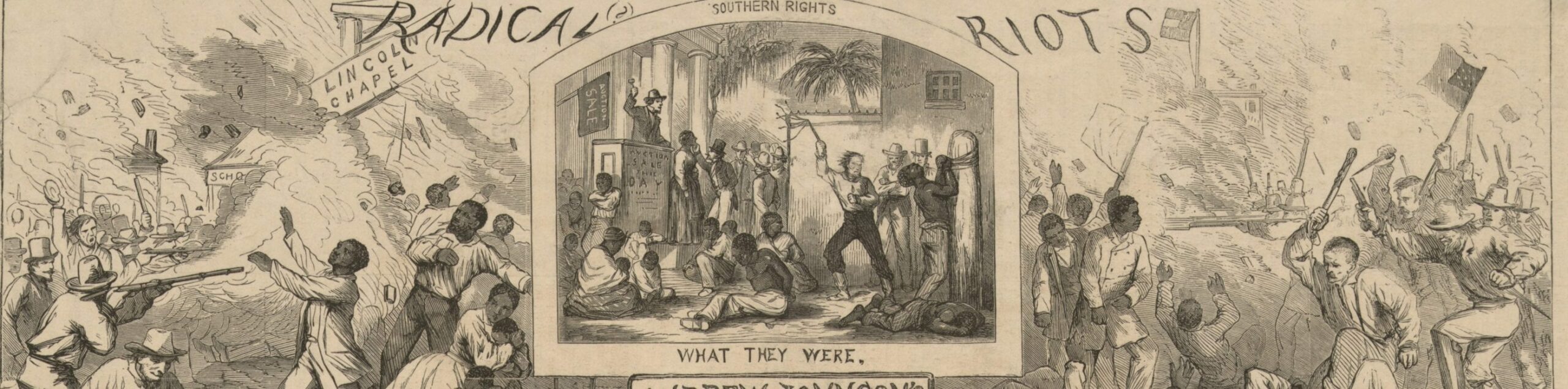

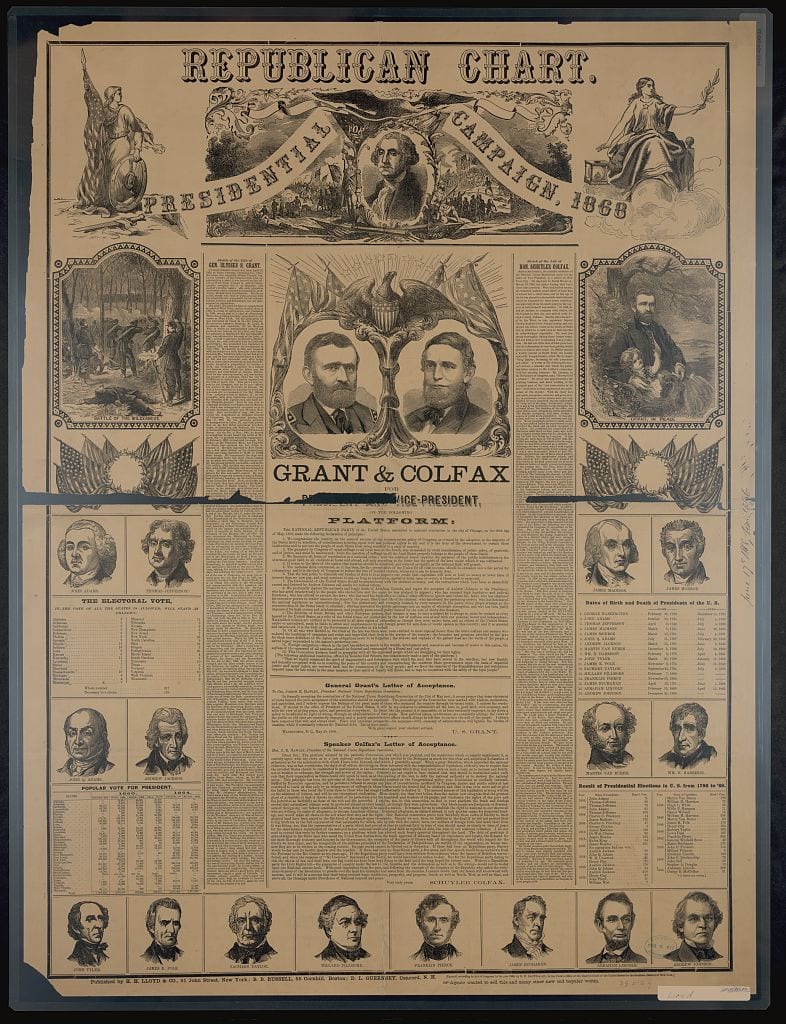

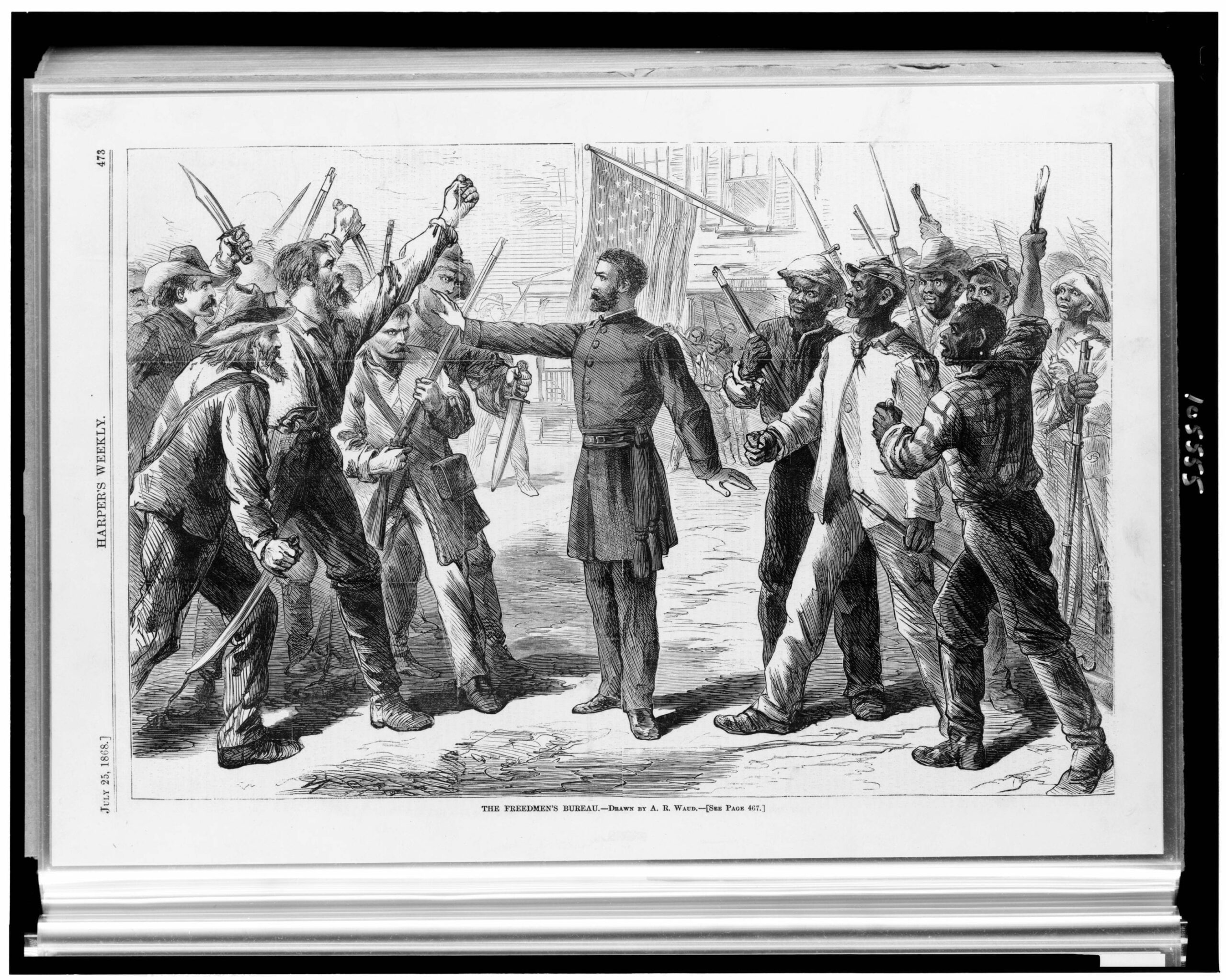

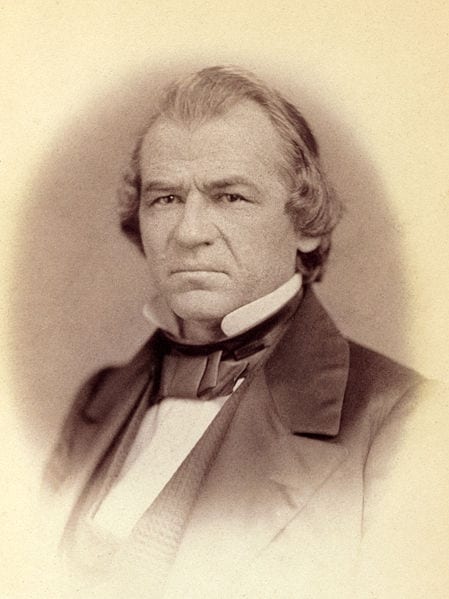

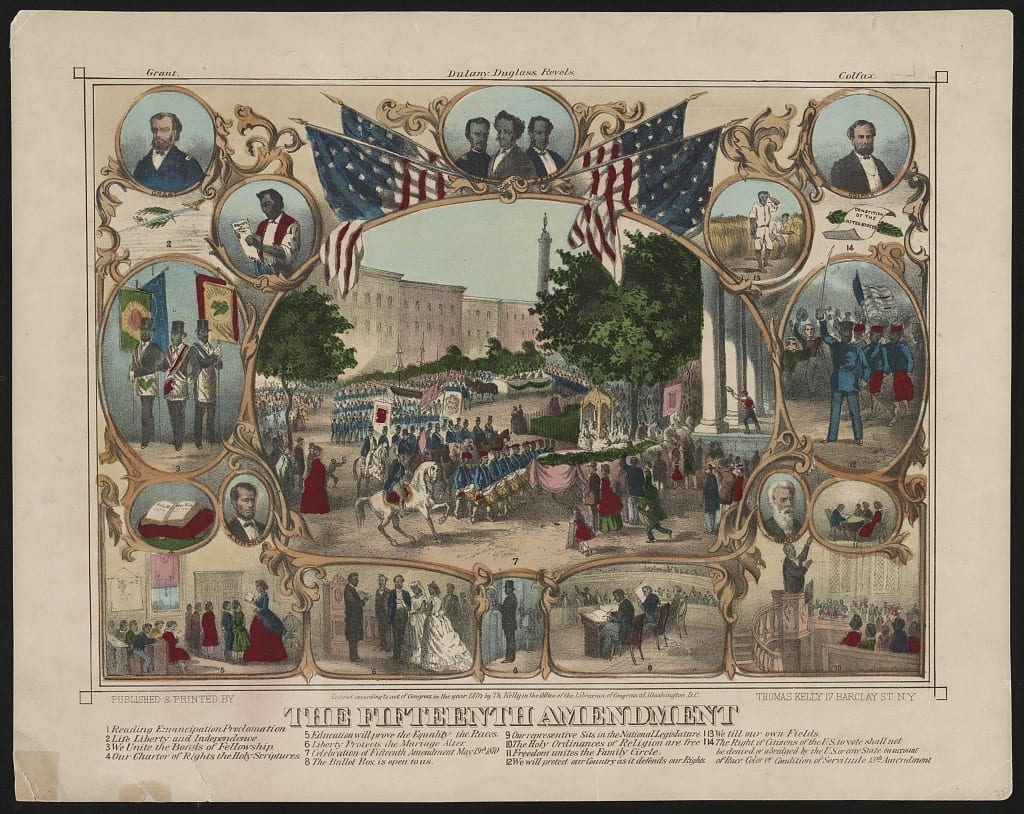

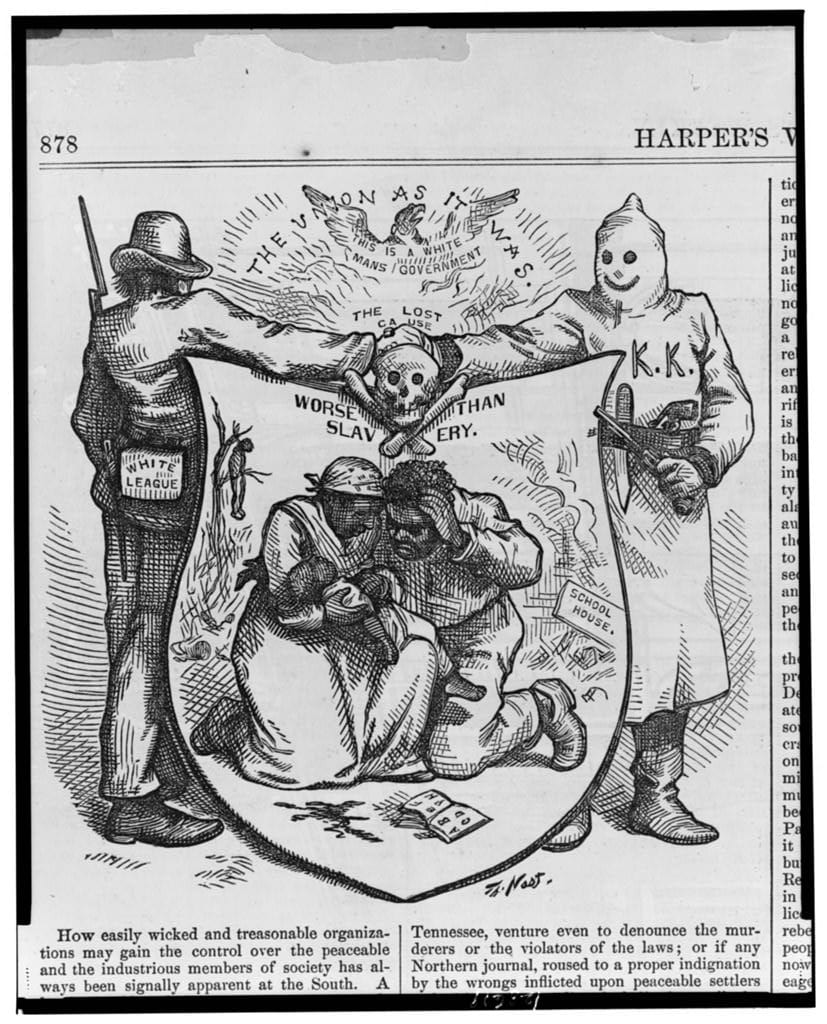

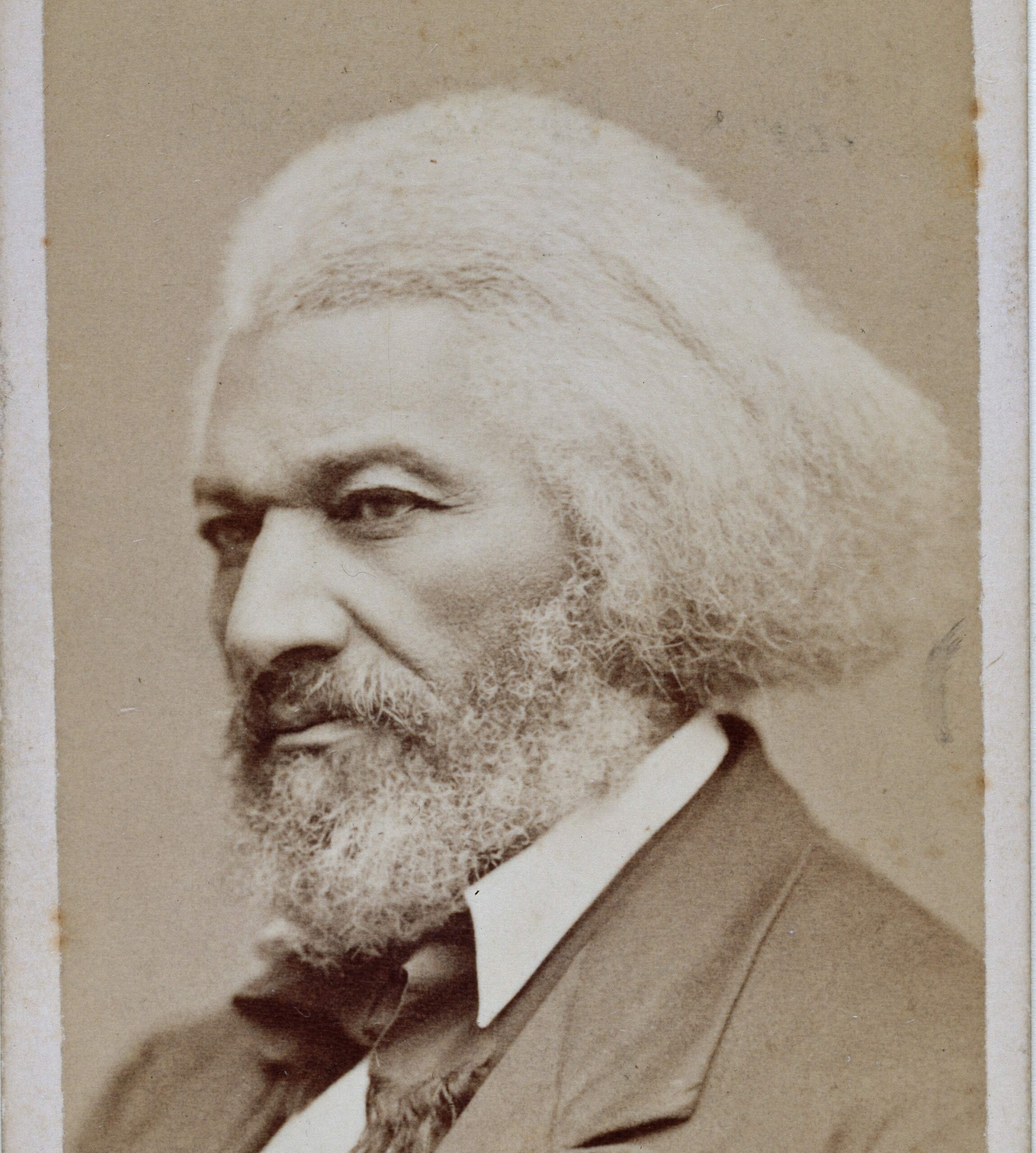

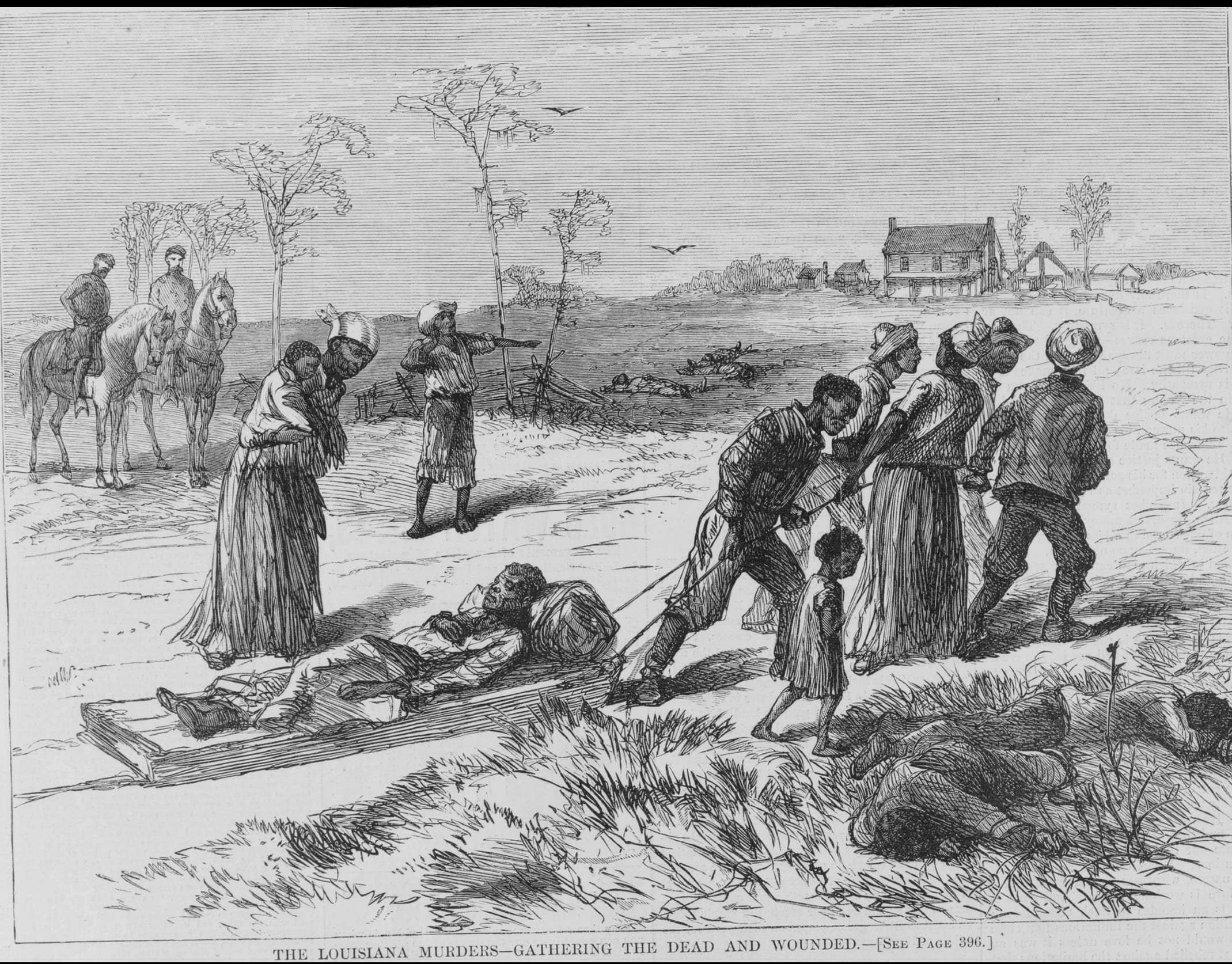

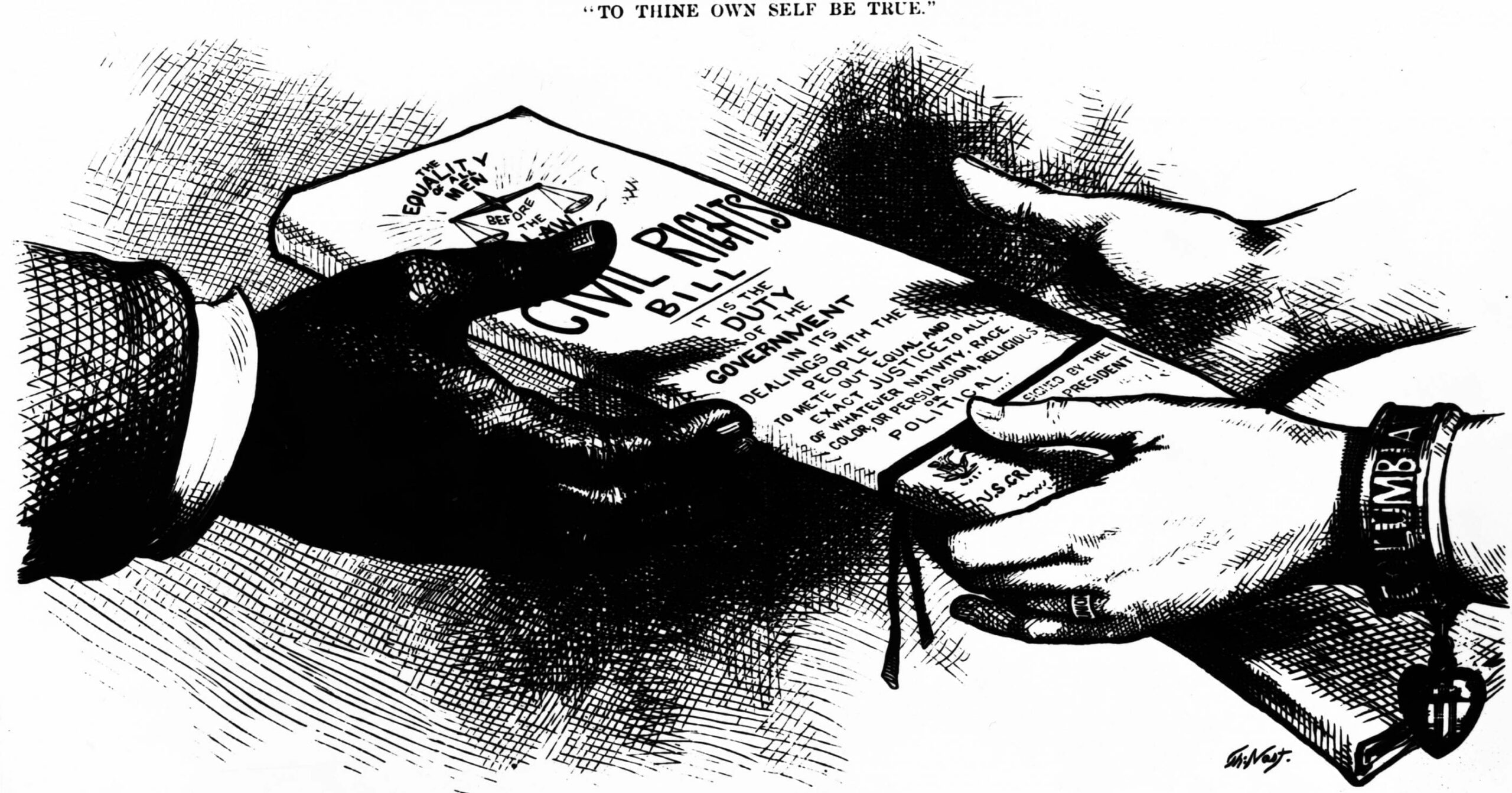

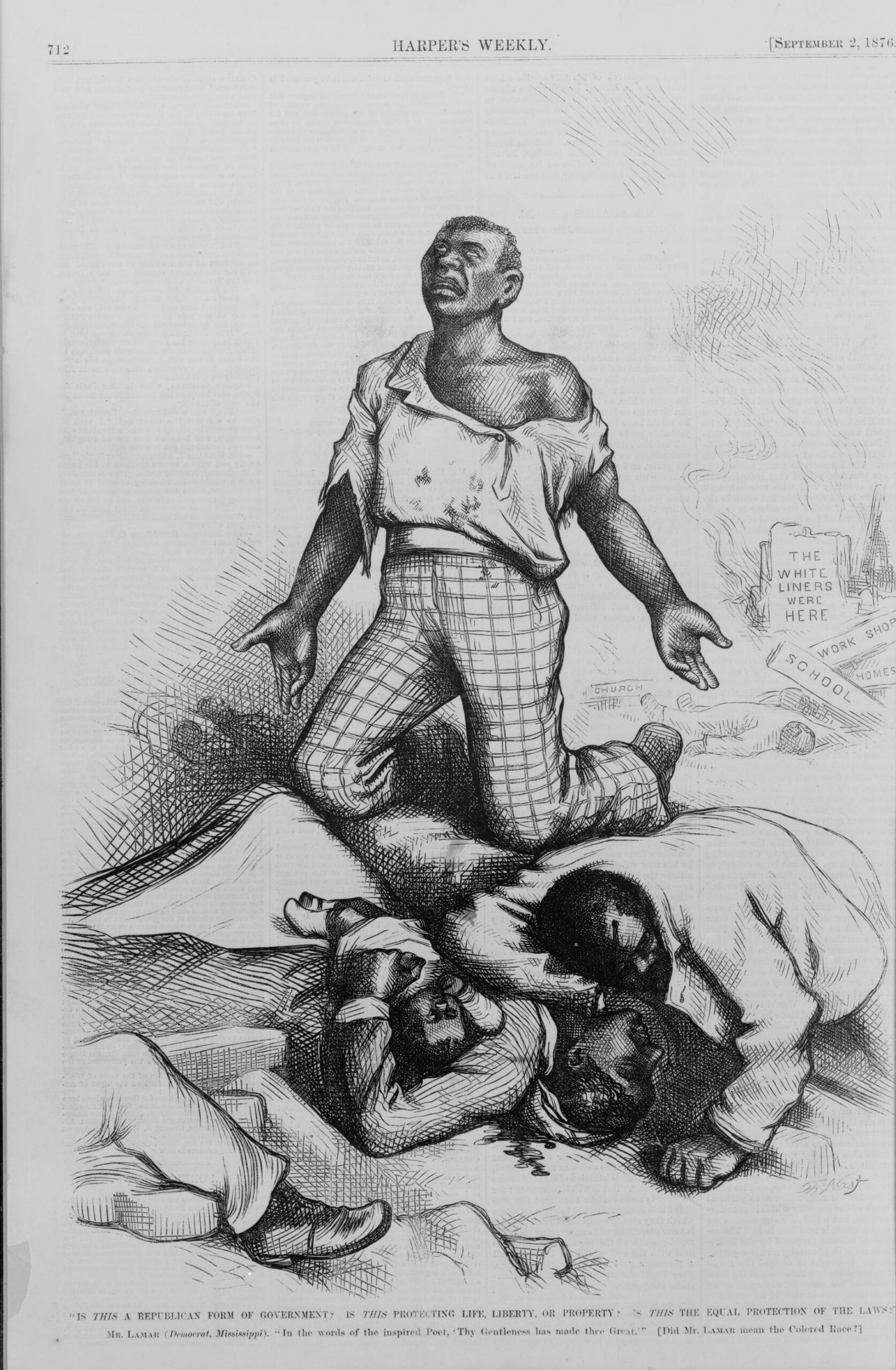

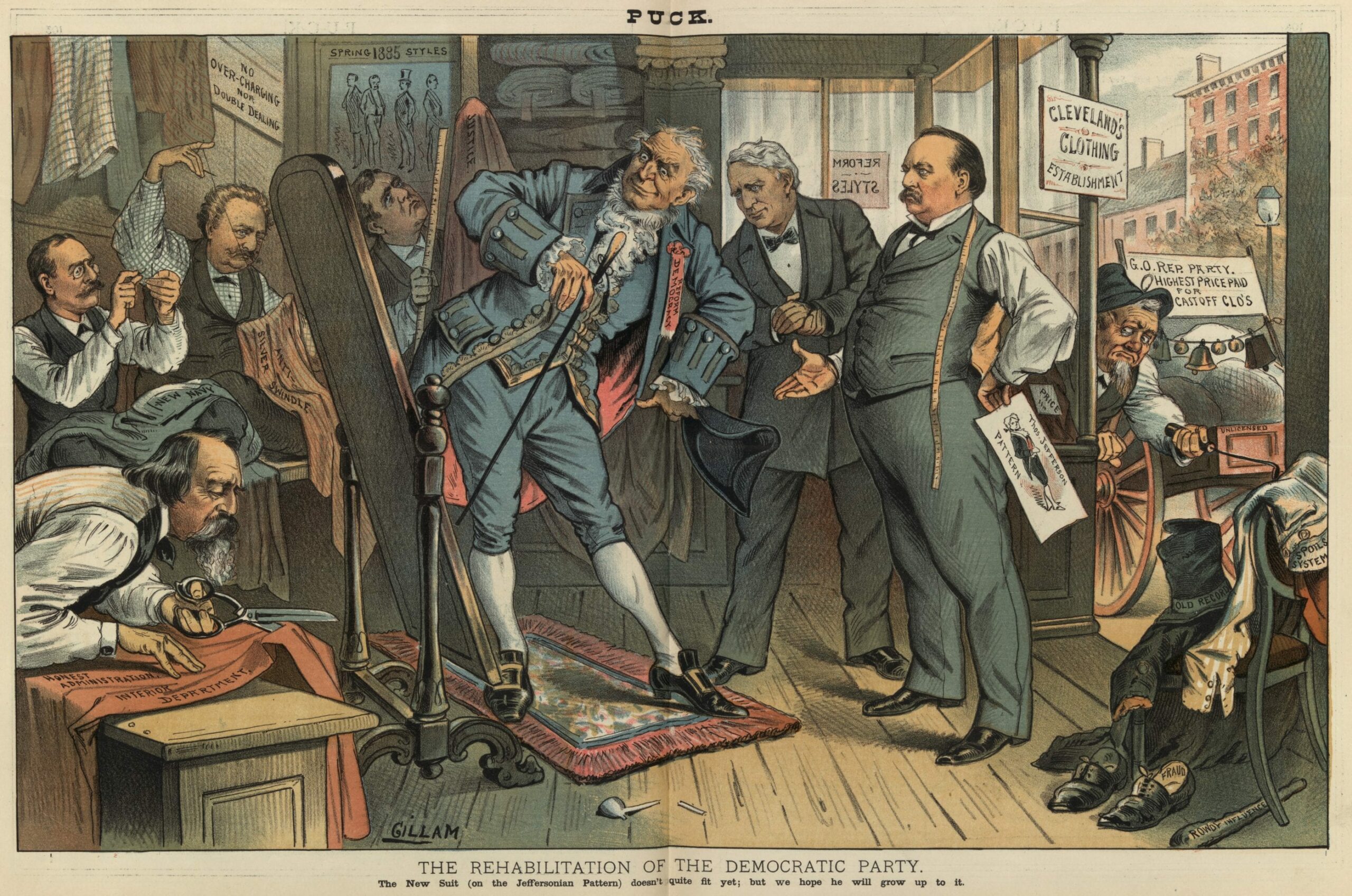

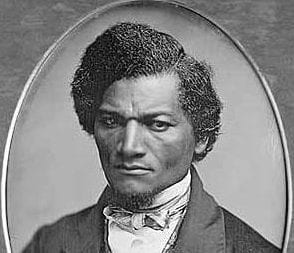

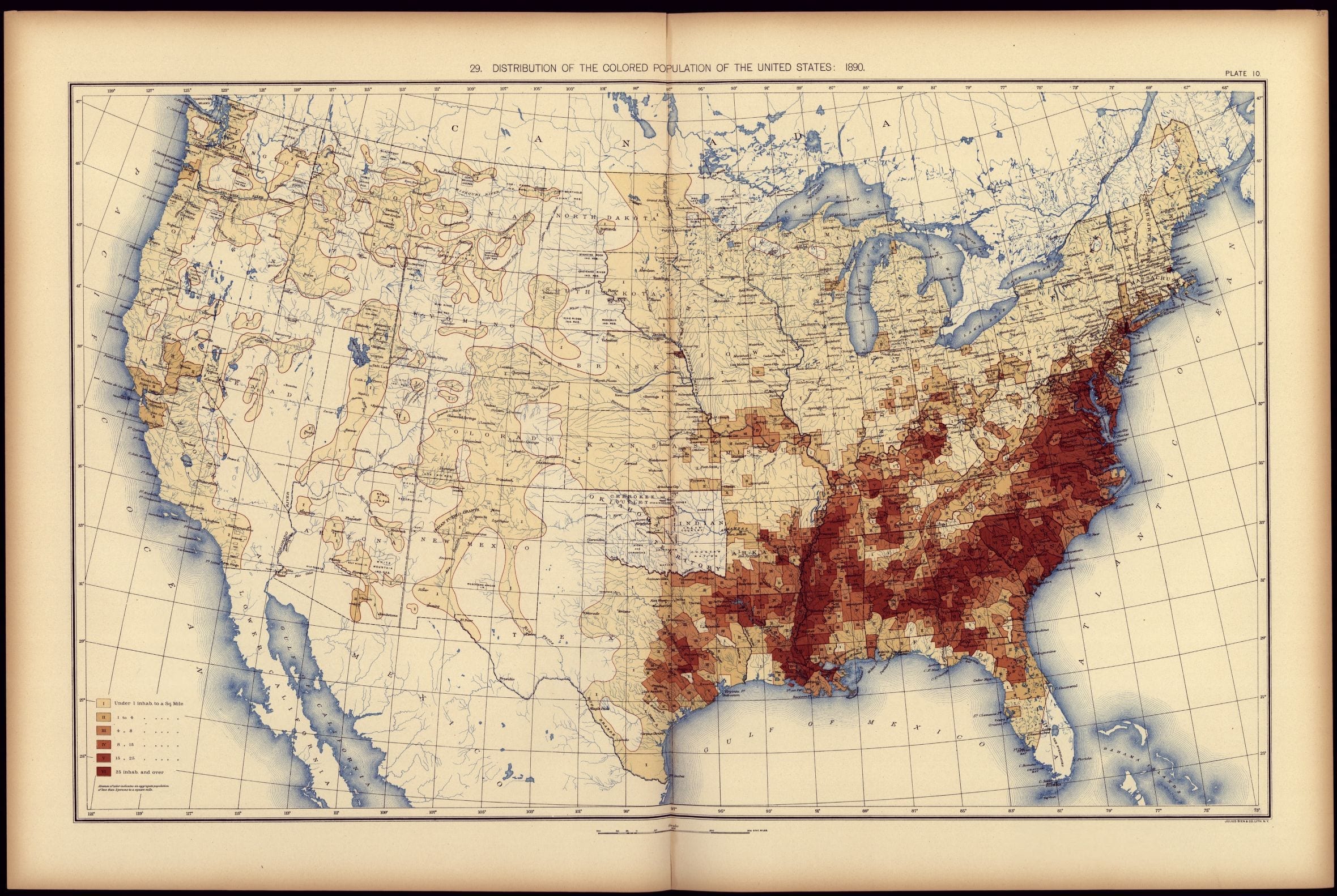

Following the end of the American Civil War and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, it was incumbent on his successor, Andrew Johnson, to pursue Reconstruction in the South. President Johnson took a more relatively lenient posture towards the Southern states, emphasizing the importance of national reconciliation. This drew the ire of the “Radical Republicans” in Congress who wanted a more punitive policy. Particularly upsetting to Congress was the fact that Johnson did little to protect newly freed slaves who were subjected to “Black Codes,” state voting regulations meant to disenfranchise them. Radical Republicans enacted stricter national legislation to negate the effects of such policies, such as the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1866, only by overriding Johnson’s vetoes.

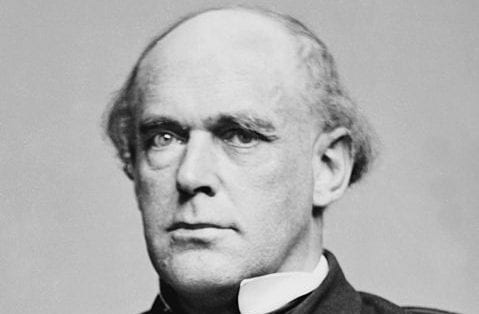

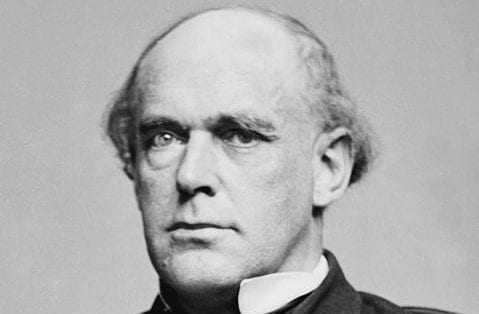

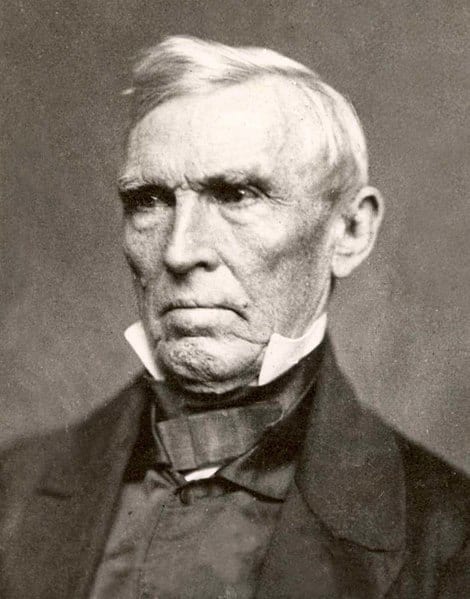

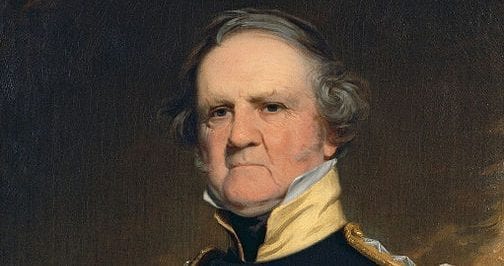

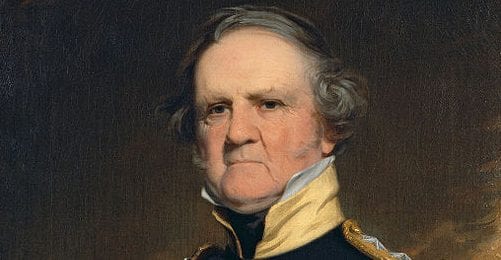

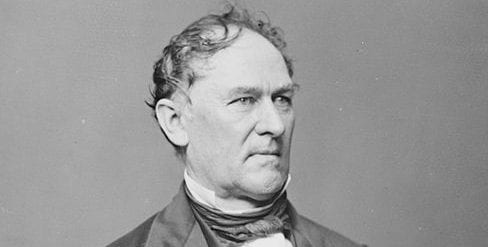

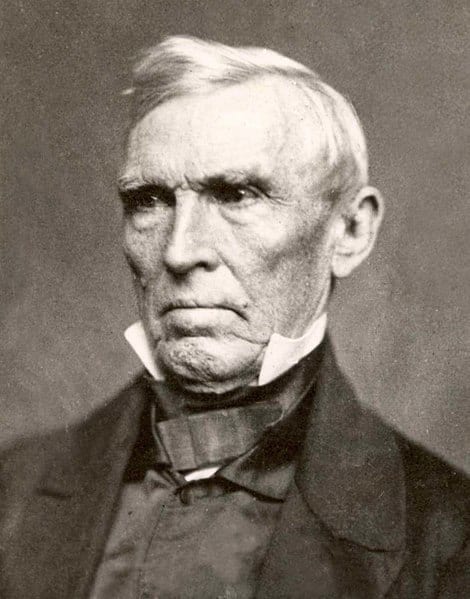

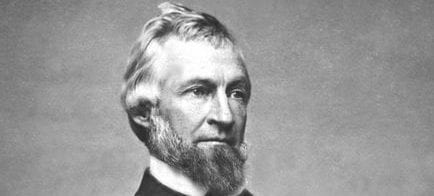

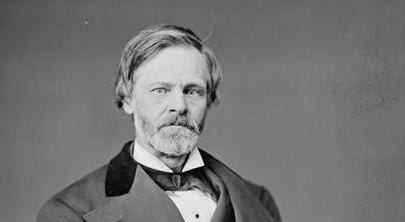

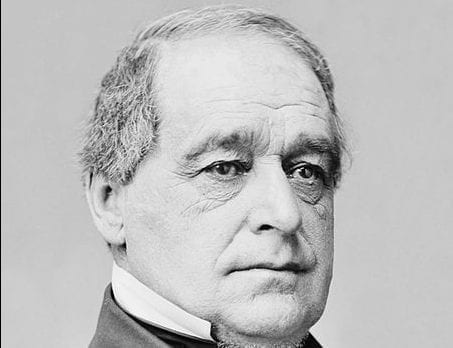

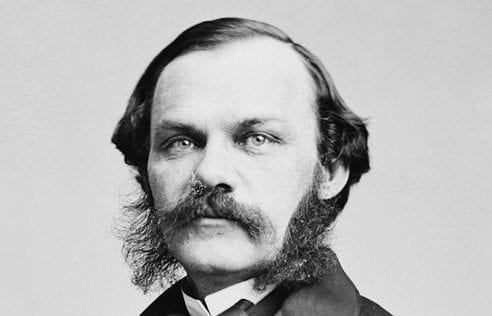

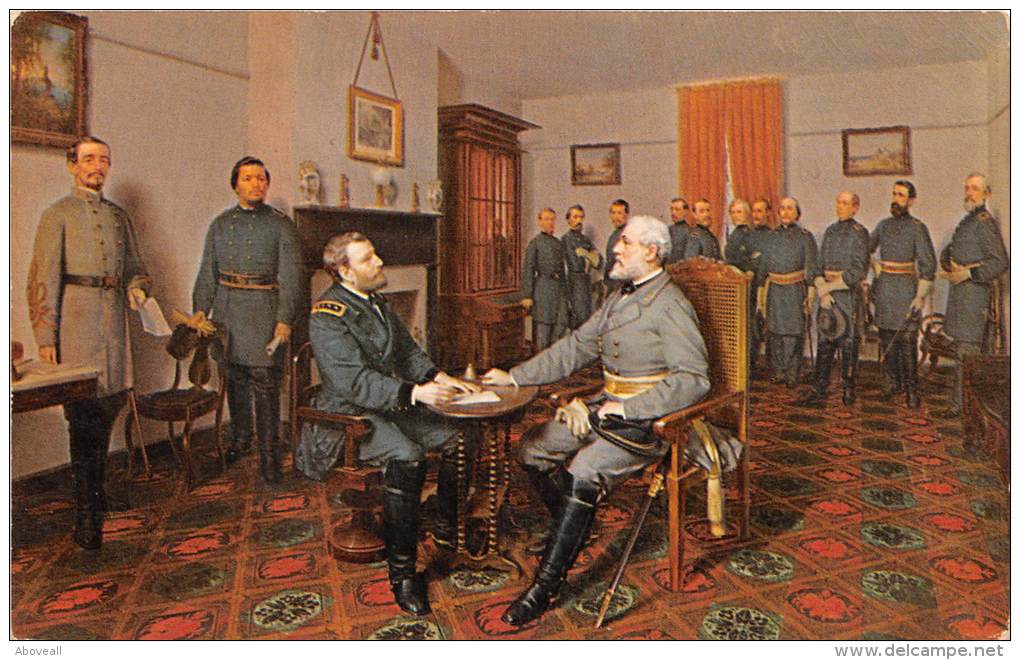

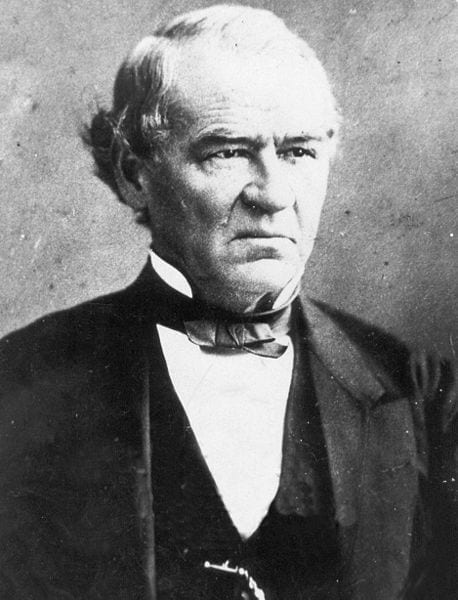

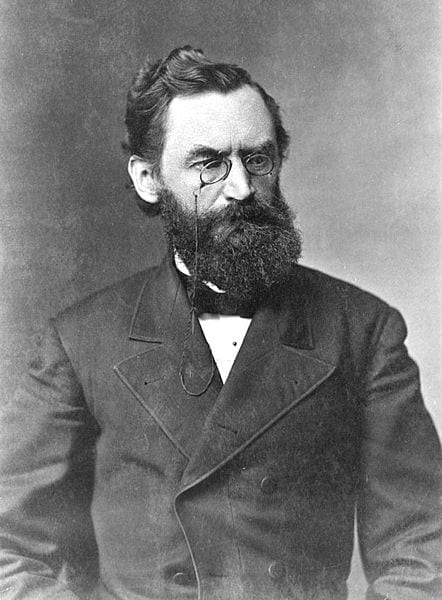

The animosity between President Johnson and the overwhelmingly Republican Congress came to a head over Johnson’s conflict with the removal of Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s secretary of war (who continued as secretary of war under Johnson). Stanton sided with the Radical Republicans and used his authority as war secretary to push for strict measures against the South while the North still occupied it militarily.

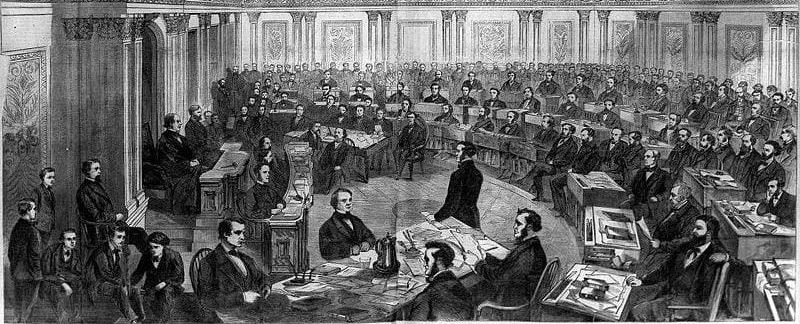

Johnson considered firing his inherited war secretary, but Congress anticipated this by passing the Tenure of Office Act (1867), which made the advice and consent of the Senate necessary. The act required the Senate’s advice and consent for all presidential removals from office, in contradiction to the policy adopted by the First Congress in the “Decision of 1789” (see A Debate on the President’s Removal Power: “The Decision of 1789”). Johnson believed the law was unconstitutional and removed Stanton from office anyway. Relations between the two branches continued to deteriorate until ultimately, Radical Republicans pursued impeachment against President Johnson, citing not only his violation of the Tenure of Office Act to ignore the Senate’s role in the appointment and removal process but also his derogatory remarks about various members of the Congress as causes. In the end, Republicans in the Senate fell just one vote shy of removing Johnson from office.

Source: “Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson,” available online at The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/john_chap_07.asp#articles.

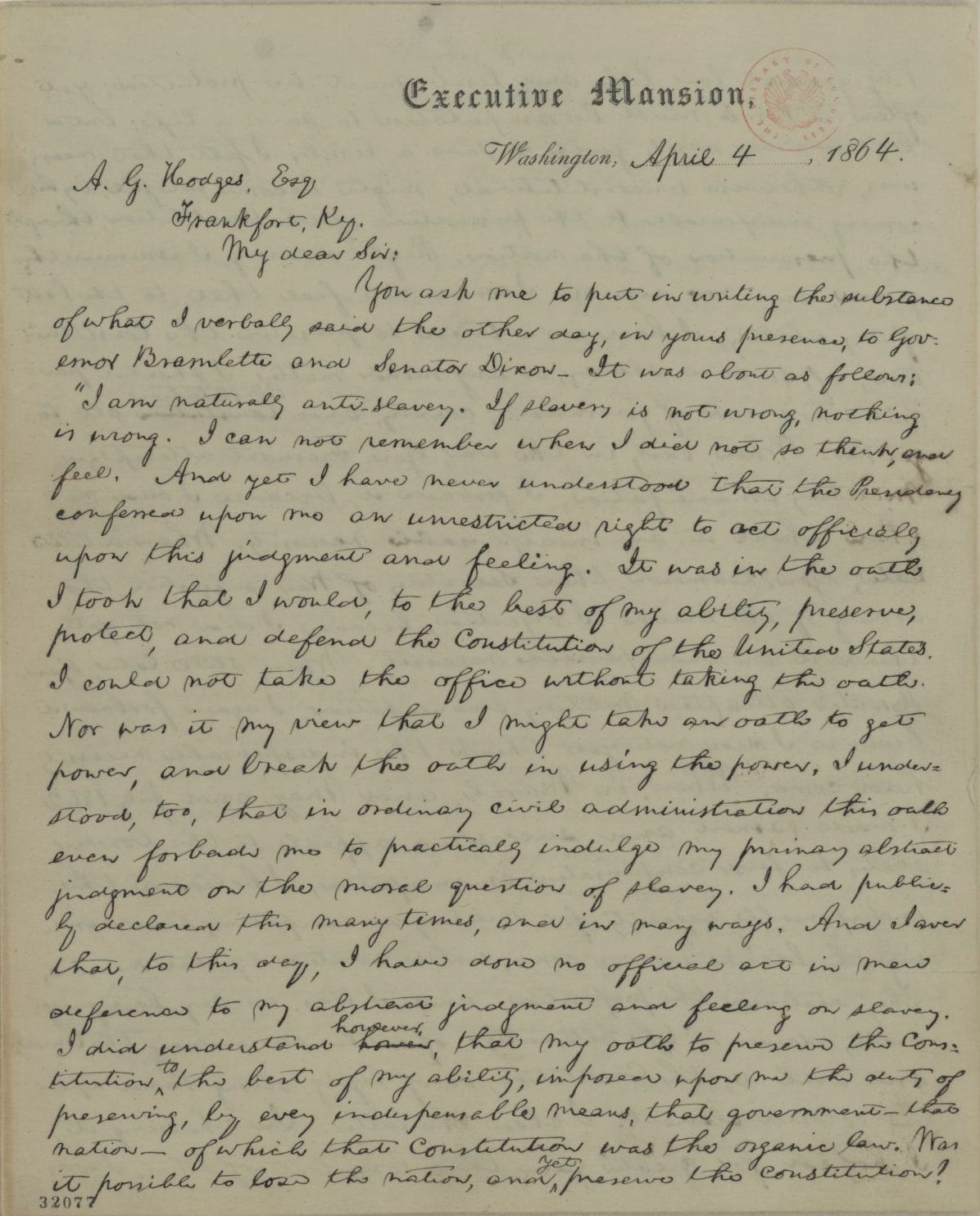

Article I

That said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States . . . did unlawfully, and in violation of the Constitution and laws of the United States, issue an order in writing for the removal of Edwin M. Stanton from the office of secretary for the Department of War,

said Edwin M. Stanton having been theretofore duly appointed and commissioned, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the United States, as such secretary,

and said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, on the 12th day of August, in the year of our Lord 1867, and during the recess of said Senate, having suspended by his order Edwin M. Stanton from said office,

and within twenty days after the first day of the next meeting of said Senate, that is to say, on the 12th day of December, in the year last aforesaid, having reported to said Senate such suspension with the evidence and reasons for his action in the case and the name of the person designated to perform the duties of such office temporarily until the next meeting of the Senate,[1]

and said Senate, there afterward, on the 13th day of January, in the year of our Lord 1868, having duly considered the evidence and reasons reported by said Andrew Johnson for said suspension, and having refused to concur in said suspension. . . .

and said Edwin M. Stanton, by reason of the premises, on said 21st day of February, being lawfully entitled to hold said office of secretary for the Department of War, which said order for the removal of said Edwin M. Stanton. . . .

Which order was unlawfully issued with intent then and there to violate the act entitled “An act regulating the tenure of certain civil offices,”[2] passed March second, eighteen hundred and sixty-seven, and with the further intent, contrary to the provisions of said act, in violation thereof, and contrary to the provisions of the Constitution of the United States, and without the advice and consent of the Senate of the United States, the said Senate then and there being in session, to remove said Edwin M. Stanton from the office of secretary for the Department of War, the said Edwin M. Stanton, being then and there secretary for the Department of War, and being then and there in the due and lawful execution and discharge of the duties of said office, whereby said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, did then and there commit, and was guilty of a high misdemeanor in office.

Article II

That on said twenty-first day of February, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-eight, at Washington, in the District of Columbia, said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, unmindful of the high duties of his office, of his oath of office, and in violation of the Constitution of the United States, and contrary to the provisions of an act entitled “An act regulating the tenure of certain civil offices,” passed March second, eighteen hundred and sixty-seven, without the advice and consent of the Senate of the United States, said Senate then and there being in session, and without authority of law, did, with intent to violate the Constitution of the United States, and the act aforesaid, issue and deliver to one Lorenzo Thomas[3] a letter of authority in substance as follows, that is to say:

EXECUTIVE MANSION, Washington, D.C., February 21, 1868.

SIR: The Hon. Edwin M. Stanton having been this day removed from office as secretary for the Department of War, you are hereby authorized and empowered to act as secretary of war ad interim, and will immediately enter upon the discharge of the duties pertaining to that office.

Mr. Stanton has been instructed to transfer to you all the records, books, papers, and other public property now in his custody and charge. . . .

Then and there being no vacancy in said office of secretary for the Department of War, whereby said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, did then and there commit, and was guilty of a high misdemeanor in office. . . .

Article X

The following additional articles of impeachment were agreed to, viz:

That said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, unmindful of the high duties of his office and the dignity and proprieties thereof, and of the harmony and courtesies which ought to exist and be maintained between the executive and legislative branches of the government of the United States, designing and intending to set aside the rightful authority and powers of Congress, did attempt to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach the Congress of the United States, and the several branches thereof, to impair and destroy the regard and respect of all the good people of the United States for the Congress and legislative power thereof, (which all officers of the government ought inviolably to preserve and maintain,) and to excite the odium and resentment of all the good people of the United States against Congress and the laws by it duly and constitutionally enacted; and in pursuance of his said design and intent, openly and publicly, and before diverse assemblages of the citizens of the United States convened in diverse parts thereof to meet and receive said Andrew Johnson as the chief magistrate of the United States, did, on the eighteenth day of August, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-six, and on diverse other days and times, as well before as afterward, make and deliver with a loud voice certain intemperate, inflammatory and scandalous harangues, and did therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces as well against Congress as the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries jeers and laughter of the multitudes then assembled and in hearing, which are set forth in the several specifications hereinafter written, in substance and effect, that is to say: . . .

I have been slandered, I have been maligned, I have been called a Judas Iscariot and all that. Now, my countrymen, here to-night, it is very easy to indulge in epithets; it is easy to call a man Judas and cry out traitor, but when he is called upon to give arguments and facts he is very often found wanting. Judas Iscariot—Judas. There was a Judas, and he was one of the twelve apostles. Oh! yes, the twelve apostles had a Christ. The twelve apostles had a Christ, and he never could have had a Judas unless he had had twelve apostles. If I have played the Judas, who has been my Christ that I have played the Judas with? Was it Thaddeus Stevens? Was it Wendell Phillips? Was it Charles Sumner? These are the men that stop and compare themselves with the Savior; and everybody that differs with them in opinion, and to try to stay and arrest their diabolical and nefarious policy, is to be denounced as a Judas.”

“Well, let me say to you, if you will stand by me in their action, if you will stand by me in trying to give the people a fair chance—soldiers and citizens—to participate in these offices, God being willing, I will kick them out. I will kick them out just as fast as I can.

Let me say to you, in concluding, that what I have said I intended to say. I was not provoked into this, and I care not for their menaces, the taunts, and the jeers. I care not for threats. I do not intend to be bullied by my enemies nor jeers. I care not for threats. I do not intend to be bullied by my enemies nor overawed by my friends. But, God willing, with your help, I will veto their measures whenever any of them come to me.”

Which said utterances, declarations, threats, and harangues, highly censurable in any, are peculiarly indecent and unbecoming in the chief magistrate of the United States, by means whereof said Andrew Johnson has brought to high office of the president of the United States into contempt, ridicule, and disgrace, to the great scandal of all good citizens, whereby said Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, did commit, and was then and there guilty of a high misdemeanor in office. . . .

- 1. President Johnson and Congress had exceptionally contrasting opinions when it came to Reconstruction, especially on the question of an African American’s ability to vote. Johnson said that he and Edwin Stanton (who was in favor of Congress’ plan for Reconstruction), on the question of “Negro suffrage,” were “irreconcilably opposed.”

- 2. The Tenure of Office Act (effective 1867–1887) mandated that the president may only remove an executive officer with the approval of the Senate. It also stipulated that the president may suspend an official while the Senate is not in session but could be reinstated if the Senate did not agree with the president’s decision. The act was written with Edwin Stanton, a congenial Republican, in mind.

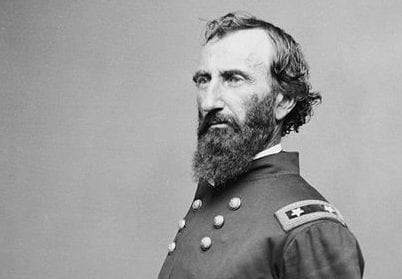

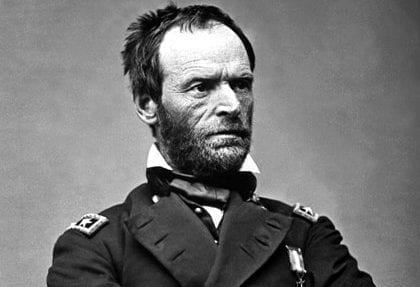

- 3. After President Johnson’s disregard for the Senate’s decision to reinstate Stanton, Johnson instead appointed Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, an adjunct general of the Army, to Stanton’s position.

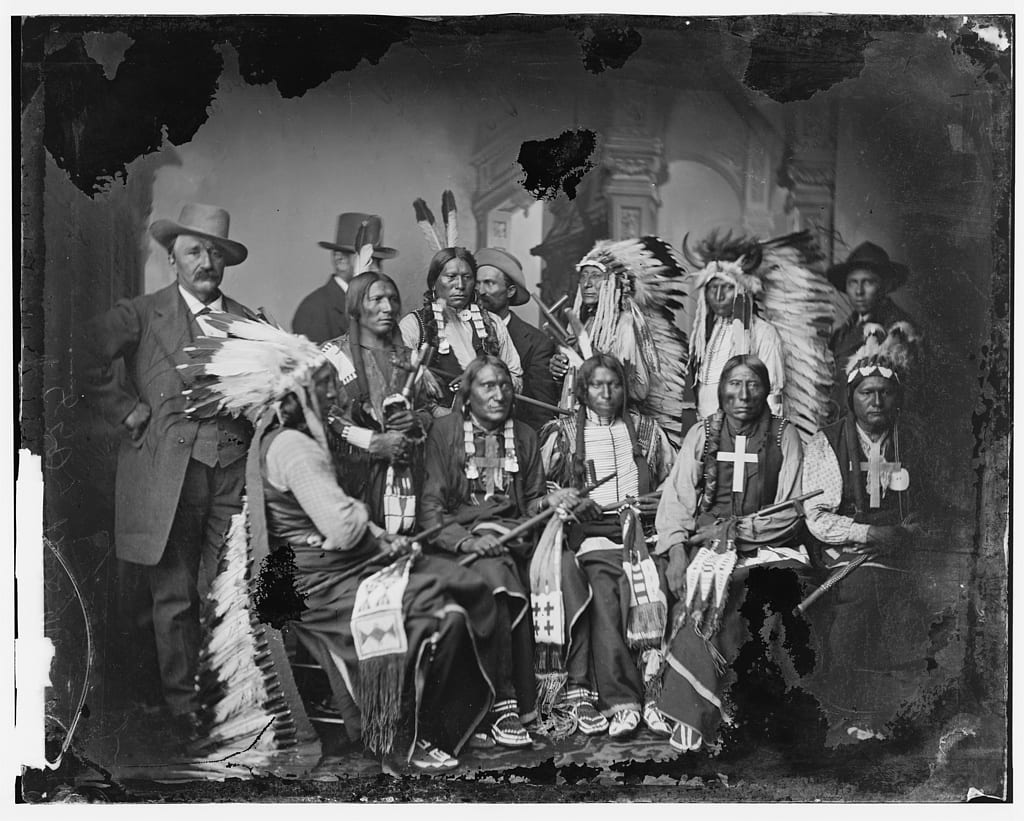

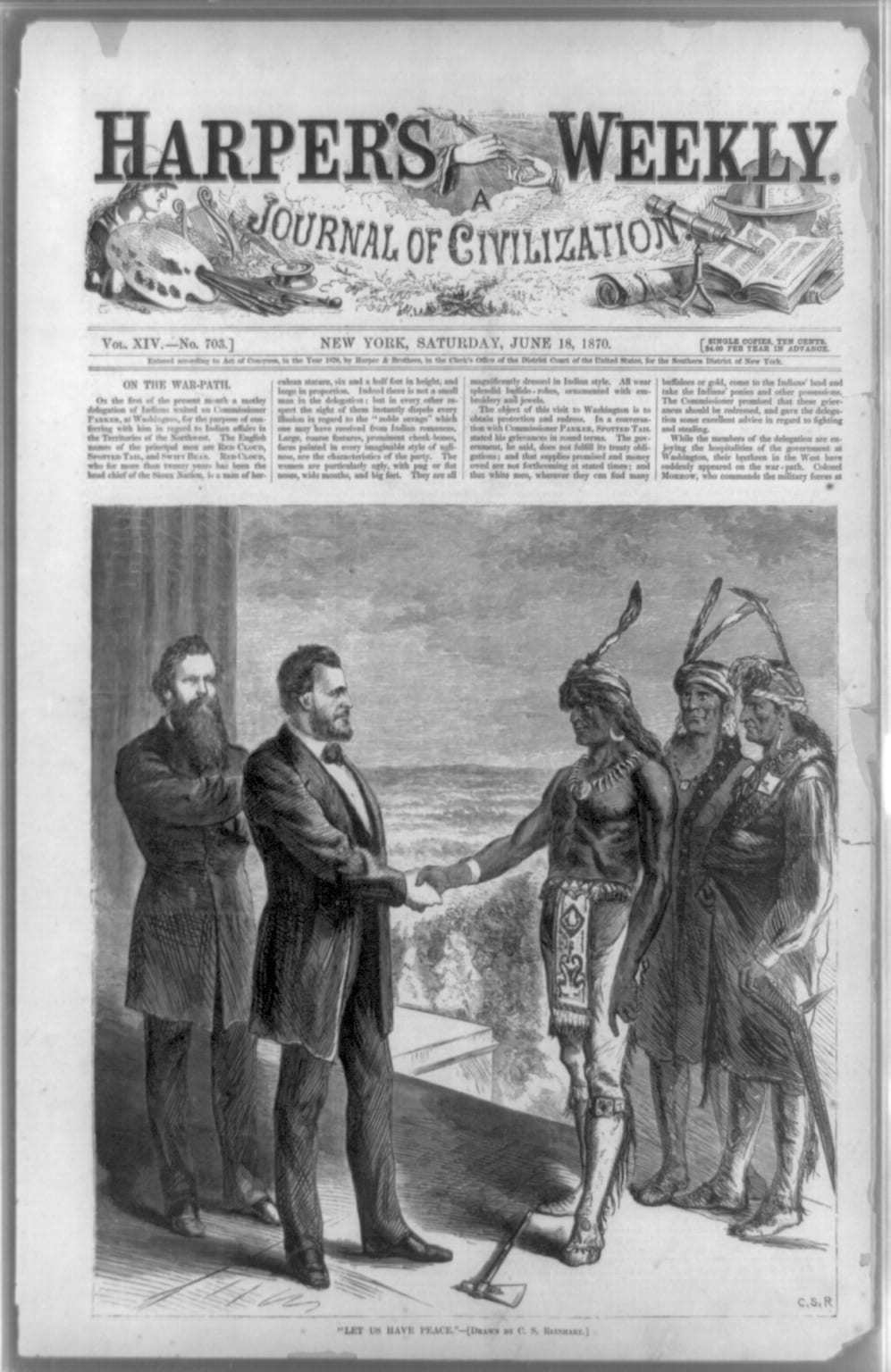

Fort Laramie Treaty

April 29, 1868

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.