Not a Modern Phenomenon: Impeachment & Partisanship

With current news focusing on the House of Representatives’ impeachment inquiry, we asked Jeremy D. Bailey, Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston, to explain the presidential impeachment process from a constitutional and historical perspective. Bailey, a visiting faculty member in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program at Ashland University, focuses his research on the executive power, constitutionalism, and American political thought and development. Author of James Madison and Constitutional Imperfection (Cambridge University Press, 2015) and Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power (Cambridge University Press 2007), Bailey also co-authored (with David Alvis and Flagg Taylor) a study of the president’s removal power. He edited Teaching American History’s core document collection, The American Presidency, a volume that gathers excerpts of several of the texts Bailey refers to in the following interview.

1. The House is conducting an “impeachment inquiry.” How does this differ from an actual impeachment?

An impeachment is the first of a two-step process aimed at removing a public official. To impeach a president is to accuse him of an offense rendering him unfit for office. Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution gives the House the authority to impeach federal officials, and Section 3 of Article I gives the Senate the power to remove them. We often use the word impeach to refer to both the accusation and the removal, but that’s incorrect. At present, no discussion of an official impeachment has begun.

There is no Constitutional rulebook for this. Everything is a creation of the chambers that have Constitutional responsibilities. Traditionally, the House Judiciary Committee considers the question, then votes on whether to refer the matter to the whole House for debate and vote. If the whole house votes to impeach, the Senate conducts the actual trial. So far, the House Judiciary Committee has not addressed the issue. The House Intelligence Committee is holding hearings, presumably because the whistle-blower conveyed his concerns to them after speaking with intelligence officials.

2. How does the Constitution define an impeachable offense?

Article II, Section 4 says a president can be removed from office if convicted of “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The meaning of the word “Bribery” is relatively clear. What constitutes treason is less clear, as the Burr conspiracy demonstrated. But the phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” is the most ambiguous. As university of Texas political scientist Jeffrey Tulis has shown, the Constitution invites two plausible interpretations of that clause, one political, and the other legal. Historically, the legal interpretation has prevailed.

Gerald Ford, speaking as a representative to Congress in the 1950s or 60s, applied the political interpretation when he said impeachment is “whatever the House says it is.” There is no way to define it; it’s just a matter of judgment by the chambers of Congress. But the legal interpretation insists that some sort of indictable offense is the necessary condition for impeachment, and this offense must be sufficiently serious and relevant to the office to suggest removal is warranted.

We’ve seen three presidential impeachments and fifteen of other federal officials (most of them federal judges). In the most recent case, that of President Bill Clinton, everybody agreed he had committed a crime—perjury under oath—but the question was whether perjury about sex was a grave enough crime and involved the president in his public capacity.

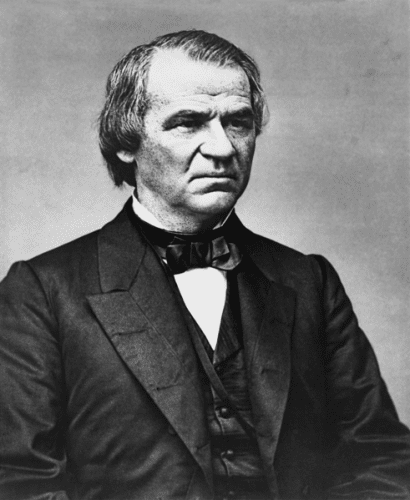

Clinton’s example demonstrates the partial victory of the legal understanding over time. That is, we have emphasized the legal interpretation because the accused have leaned on it in their defense. Two other important precedents are the impeachment of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in 1804 and the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in 1868.

The Jeffersonian Congress believed that the Federalist Chase had abused his authority as a judge while doing federal circuit court duty Chase was very aggressive in enforcing the Sedition Act. He got on horseback and put Republican newspaper editors in jail. Then, during their trials, Chase, from the Republican perspective, made partisan decisions on the evidence admitted and witnesses allowed to testify. Most important, during his charge to a jury in Baltimore, Chase advised them that a spirit of mobocracy was sweeping across the land and it was their job to stop it. He implied that the Jeffersonians were threatening law and order.

Still, Congress knew Chase’s partisan actions did not violate any law. So, to lay the groundwork to impeach Chase, Congress first impeached and removed Federal Judge John Pickering. He was a notorious alcoholic who showed up in court drunk. There was nothing criminal about being a drunk, yet the Constitution presumably allows Congress to remove judges who are not doing their job. Having thus flexed their muscles, Congress next went after Chase. There’s some speculation that, had they succeeded in removing Chase, they would have gone after Chief Justice John Marshall next. Yet, even though the Republicans controlled over two thirds of the Senate, they did not get the necessary two-thirds vote to remove Chase. He retained his job, and that has largely been seen as a victory for the presumption that there has to be an indictable offense as the minimal condition for impeachment. Nevertheless, Chase’s impeachment chastened the Court. Justices learned they could not overtly mix political activities with their jurisprudence.

In 1868, Republicans, angered that President Andrew Johnson was obstructing their plan for Reconstruction, tried to impeach him. When the initial effort failed to get a majority in the House, Republicans set a trap. They passed the Tenure of Office Act, knowing that Johnson wanted to remove War Secretary Edwin Stanton, with whom he frequently argued. During his Senate trial, Johnson argued that appointing and firing cabinet members was part of his Constitutional function. Even though Republicans held more than two thirds of the Senate seats, the effort to remove Johnson failed by one vote.

Thanks to the Chase and Johnson examples, the legalist understanding has triumphed. But there is something incomplete about that understanding. The political understanding has its virtues too, and I think there’s a reason why the Constitution is not perfectly clear on that.

3. What can be said for the political understanding?

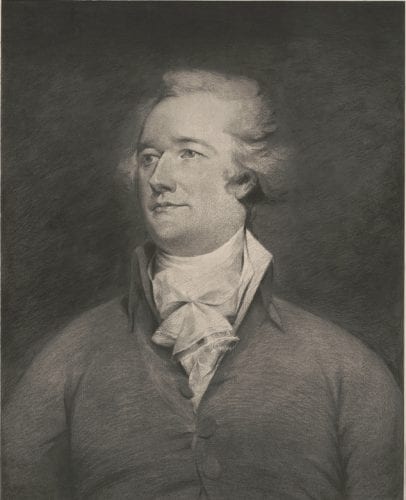

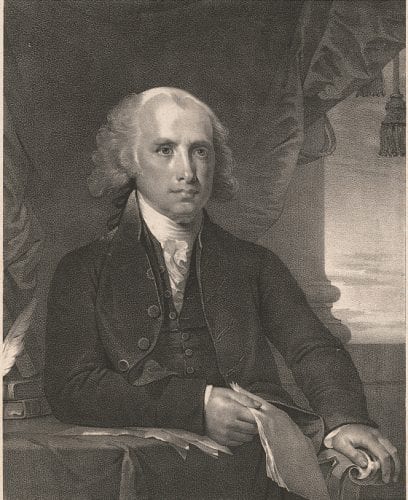

There are two pieces of evidence for it. In Federalist 65, Hamilton clearly describes an impeachable offense as a kind of political violation. He points out that the Constitution explicitly says that the loss of office is the only punishment that follows an impeachment, which suggests that a criminal trial will occur once the official no longer holds office. Hence the impeachment process provides a political, not a legal means of redress for the president’s violation. Second, Madison, in a speech before the House in 1789, defended the president’s power to remove cabinet officials, contending that a president who abused this power would be subject to impeachment. This would be a political check on a Constitutionally granted power.

The chief argument for the legal understanding rests on the framers’ revision of the original draft of the Constitution that had defined impeachable offenses as only “treason or bribery.” Late in the Constitutional Convention, a delegate proposed adding the word “maladministration.” But Madison objected that the word “maladministration” was too vague and elastic. It would make the president too dependent on the will of Congress. So they substituted the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” in place of “maladministration.”

However, as Raoul Berger argues in Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems, the phrase “High Crimes and Misdemeanors” was a term of art that the Americans would have been familiar with from English practice, especially from the impeachment of Warren Hastings over colonial affairs in India. In that case, “high crimes and misdemeanors” had a political ring to it.

But, to return to the way Tulis explains it, the Constitution invites two understandings for a reason. We can see why we would not want simply a legal understanding. Imagine a president who says he will appoint no Catholics to his cabinet. It’s not a crime, but it’s certainly a matter of deep concern. Or imagine a president with acknowledged alcoholism who starts to consume heavily during the second year of his term. Or imagine a president who lies in order to take the country to war. None of these things are criminal, but they are certainly impeachable. But if impeachments were simply political, you’d worry about having a de facto parliamentary system in which the president would not have his own independence.

4. Although you say political considerations have a place in impeachments, those who impeached Clinton in 1998, like those targeting Trump today, were accused of abusing the impeachment power to overturn the result of a presidential election.

The impeachment process was created before anybody realized we were going to have a two-party system. This system makes any political impeachment a partisan political process. It also makes impeachment really hard, because both parties know that no party will be able to muster a two-thirds vote in the Senate. The Johnson impeachment came close to removal, but in the case of Clinton, only 50 Senators voted for removal.

Arguably, the Founders assumed we would have had more impeachments than we have had and, certainly, more successful removals. One reason the president became so powerful in the 20th century is that impeachment had been taken off the table.

5. Do you think that the current impeachment inquiry was begun in the hope that, although there will never be a removal, the process might persuade voters not to reelect President Trump in 2020?

It’s not clear Democrats are sure impeachment would help them in the election. That’s why House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has been reluctant to move forward with impeachment. Trump’s refusal to cooperate with the inquiry seems calculated to force the Democrats to impeach him. He may well believe that impeachment will improve his chances of reelection. The Democratic Party is divided between those who consider impeachment good for their party and those who believe it risky. Those in favor of impeachment have a slight edge, but not enough to convince Pelosi to go full bore. Yet it seems inevitable she will, given the pressure from the louder element in the party.

Part of the Democrats’ strategy must be to get people on oath so that either they will start coming clean, or other stories will come out. Witness the Clinton impeachment—he was testifying under oath about whether he had sexually harassed Paula Jones prior to becoming president (presidents are not immune from prosecution for actions they took before assuming office) when the story of his relationship with Lewinsky came out. This led to his perjury.

6. Can Congress compel witnesses to testify?

As I see it, we have three equal branches. Each has its own Constitutional function. But it’s not clear how much power each branch has to compel another branch to do its will. Some claims of executive privilege are sensible, and some not so sensible. No bright line distinguishes between the two. The clearly sensible ones stay privileged, and the not so sensible ones do not, and these things are decided in negotiation between the two departments. The departments don’t want a zero-sum conflict resulting in one department reigning supreme.

Since the decision to impeach is the key bargaining chip held by Congress during this negotiation, what leverage do they retain after they use that chip? Perhaps they could vote on more articles of impeachment, but would that exert enough pressure? I’d guess that if there is a formal vote to refer the matter to the House Judiciary Committee, as is traditional, and if Republicans on that committee are involved in the process in the usual and traditional way, then there will be pressure on Trump to cooperate with the House Judiciary Committee’s actions. If he does not cooperate, moderate Republican Senators may turn against him when a vote on removal occurs. They may feel Trump’s refusal to act fairly justifies removal.

7. At what point might the Supreme Court get involved?

Historically, the Court has not wanted to get involved. The impeachment process itself, even though it may hinge on the presumption of a crime, is clearly a political process. However, if a trial of one of the president’s subordinates takes place during the process, the Supreme Court might have to rule on any claim of executive privilege. That’s what happened in the Nixon case; tapes of his conversations were subpoenaed in the trial of a former aide. Nixon claimed the tapes involved national security, but the Court said that the presiding judge had the right to review the tapes in the privacy of his chambers and determine whether national security really was at stake.

8. What possible risks to the nation do impeachments bring? When, in your view, is an impeachment worth these risks?

I’m sympathetic to the argument that we need a more muscular impeachment power. This could help re-balance the powers of the legislative and executive branches, perhaps chastening presidents. In 2016, I said that I thought it likely that whoever won the election would face impeachment, and that this wouldn’t be a bad thing. I’m also on record as saying we ought to have an impeachment about every 19 years or so (that’s of course a flippant allusion to Jefferson). Yet impeachment imposes risks and costs. Foreign governments may take advantage of us during the process. Domestic legislation will stall. With Congress more polarized than it has ever been, we’ll be unable during the impeachment process to pass any sensible legislation.

9. Do you expect the House will impeach the president?

At present, everything is distorted by partisan lenses. It will take a while for the facts to emerge. Then each party will reassess what serves its advantage.

Republicans may want to get the matter referred to the Senate as soon as possible, so that the Senate can kill it. Democrats may decide to keep the investigation alive yet not move to impeach.

If you want to test for partisan bias on the part of those currently arguing for or against impeaching President Trump, pull up what they said about the impeachment proceedings in 1998. If their current view of what constitutes an impeachable offense is inconsistent with what they argued at that time, you can conclude their views reflect partisanship. Citizens should remain sober, trying to understand what the Constitution allows, instead of leaping to a position that serves a temporary partisan advantage.