Congress

What’s wrong with our Congress? Judging by its approval ratings over the past decade, Congress has lost the support of the American people. Once considered to be the great American contribution to constitutional government—being governed by our own consent through elected, representative lawmakers—Congress is now the most disliked part of our political system. Over the past decade, Congress has not once reached a 30 percent approval rating or above.

It hasn’t always been this way. While Congress has never been very popular, its approval ratings during the 1990s were typically in the 40s and 50s. Today, they hover in the teens and the 20s. What has caused the public to turn against its own elected representatives?

The causes of Congress’s decline are numerous, but understanding these causes requires careful attention to intricate rules and procedures that are little-known, and rarely the subject of careful reporting. The public, as a result, typically doesn’t understand how Congress actually works. It knows that something is wrong with our legislative branch, but it doesn’t know what happened.

The materials in this book attempt to explain how Congress was designed to work, how it has changed over time, and how it functions today. Through the careful study of primary sources, chronicling the arguments and thoughts of the people who were involved in designing and reforming our legislative branch, we can come to a better understanding of what happened to our first branch of government. It is not easy to understand, or to teach, complicated procedural rules such as the role of the House Rules Committee, how members of Congress are assigned to committees, and so forth, but we can only understand Congress by examining these issues and the constitutional principles underlying the debates surrounding them.

The Nature of Representation: Delegates or Trustees?

The documents in this book address the three broad questions that are the most critical to understanding and evaluating Congress. The first question is the nature of representation in the American political system. This debate was largely the focus of, and was largely resolved by, the debate between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

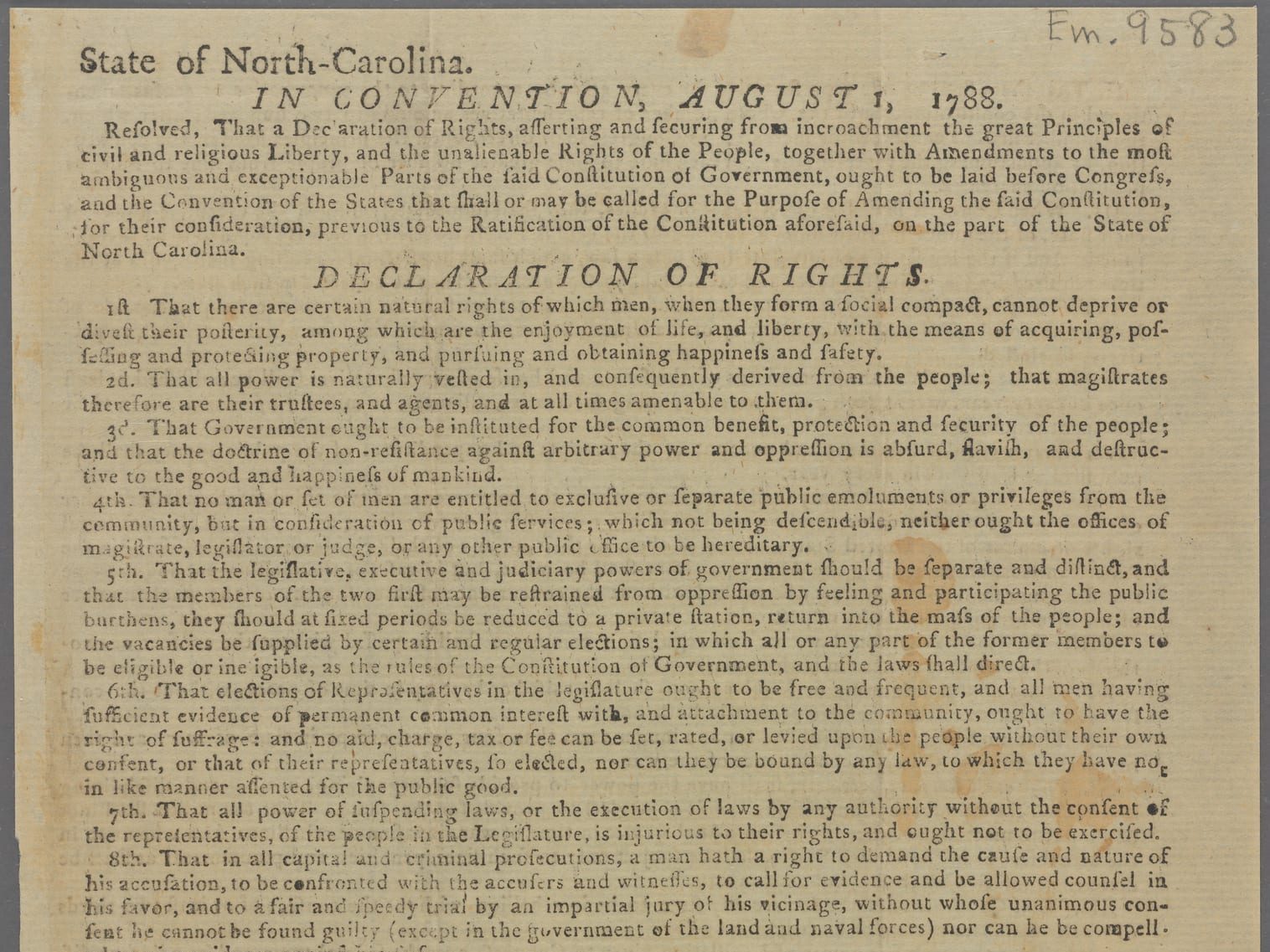

Anti-Federalists were extremely concerned about the perceived inadequacy of representation in Congress—that there were too few representatives, that they were elected for terms that were too long, that there was no provision for rotation in office or term limits, and that therefore the Congress would become a fixed, aristocratic, elite, establishment in the national capitol (see Cato No. 5 through 5). They therefore advocated shorter, annual terms for the House (see Cato No. 5), rotation in office and the ability to recall representatives, and a dramatic increase in the number of representatives (Federal Farmer No. 7, Federal Farmer, No. 11, and Brutus No. 16).

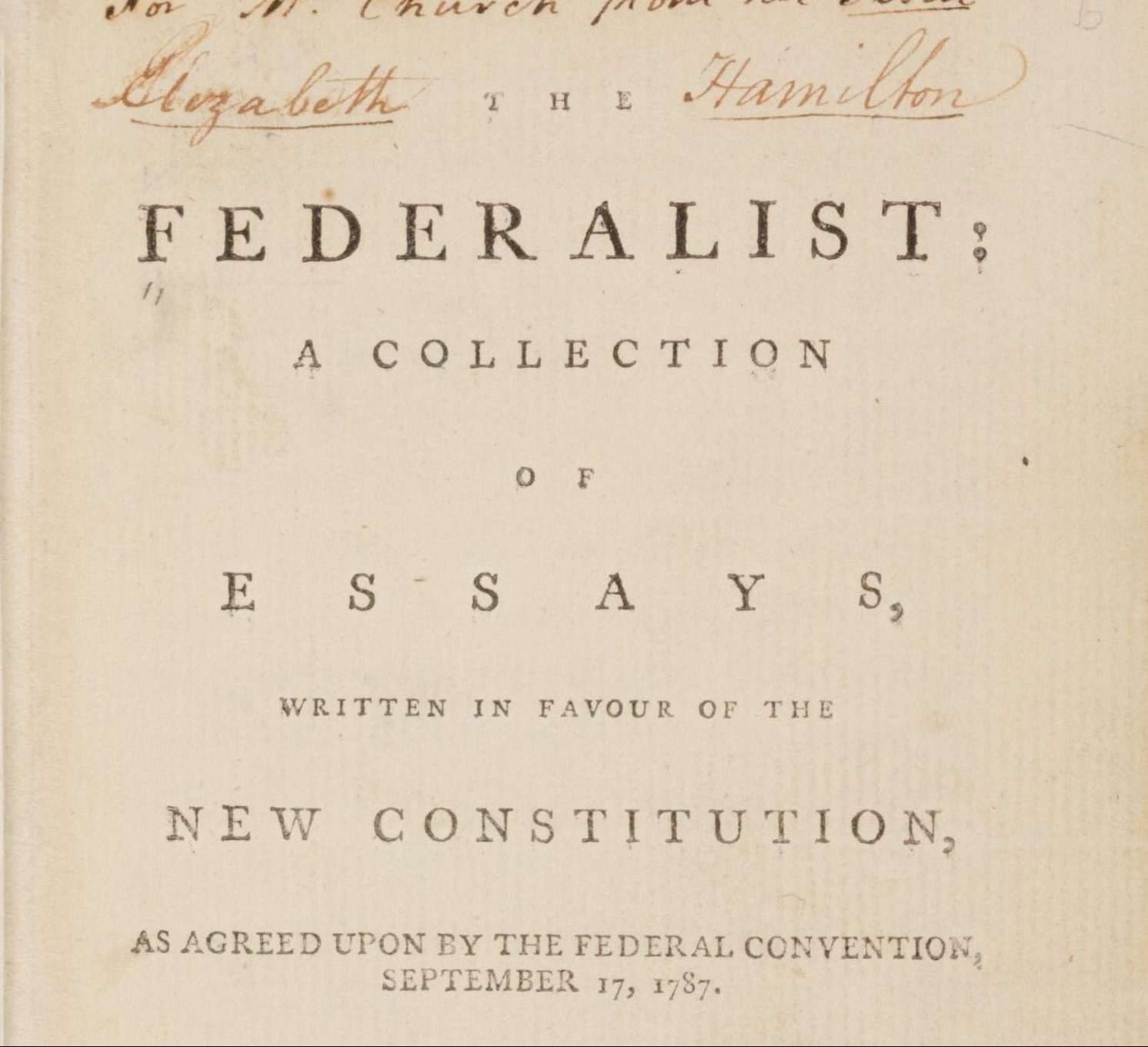

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, the primary authors of The Federalist Papers, responded to Anti-Federalists by emphasizing the accountability of the representatives to the people (see Federalist 52), but by also making the case for some space between the representatives and the people so that members of Congress could refine and enlarge the public views, serving as a filter to eliminate the pernicious elements of public opinion (see Federalist 10, 62, and 63).

The debate between the Anti-Federalists and the Federalists was not simply a historical debate about representation. It addressed a fundamental question about what kind of representation works best. Should representatives act as delegates who mirror their constituents, or should they act as trustees, voting for what they think is right regardless of their constituents’ views? In other words, is liberty endangered by a government of elites, who ignore their constituents, or by a government that is too democratic, with majority tyranny? This debate continues today, as Americans debate whether they are ruled by an out-of-touch “Washington Establishment,” of which (some argue) Congress is a central part.

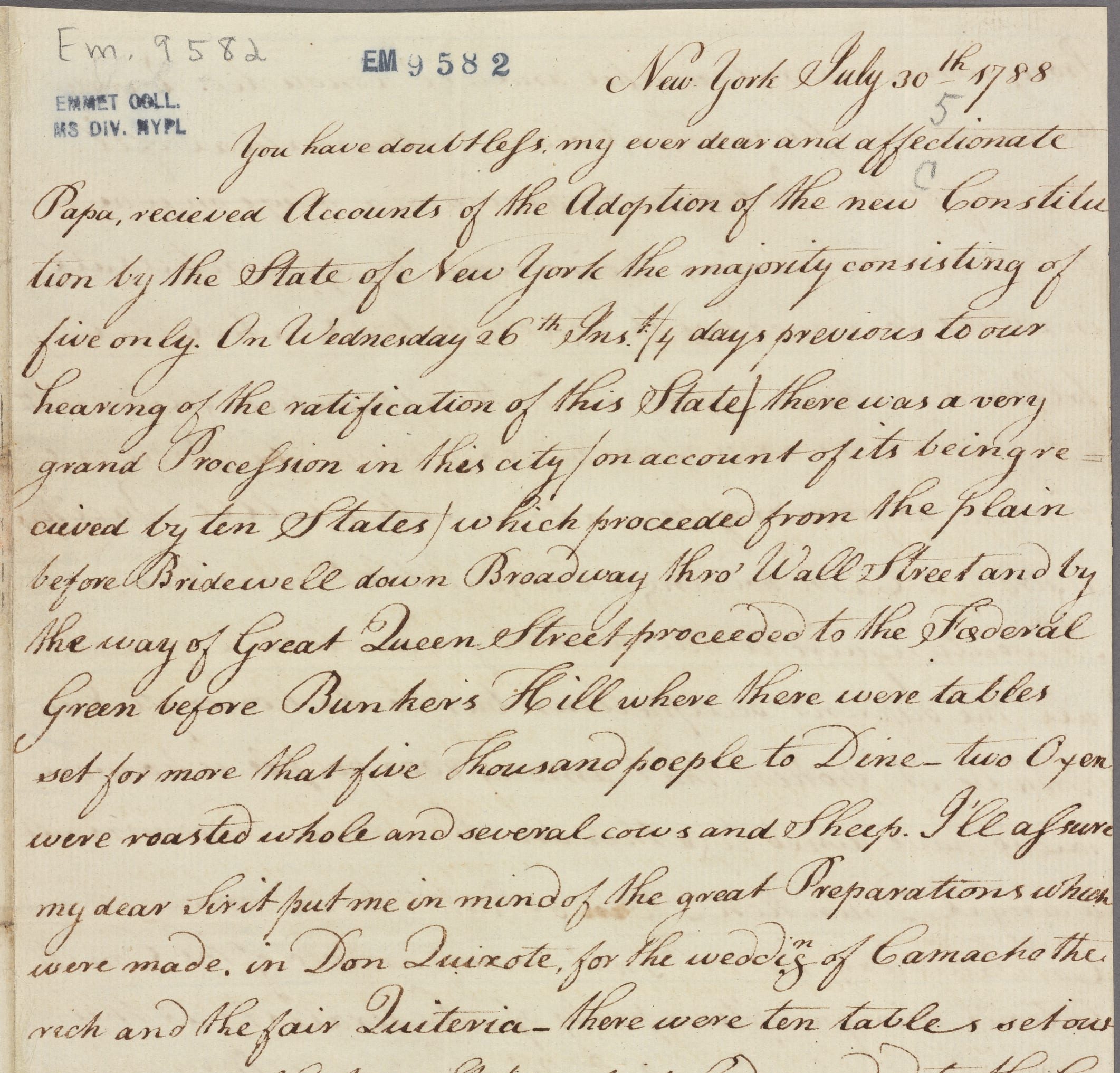

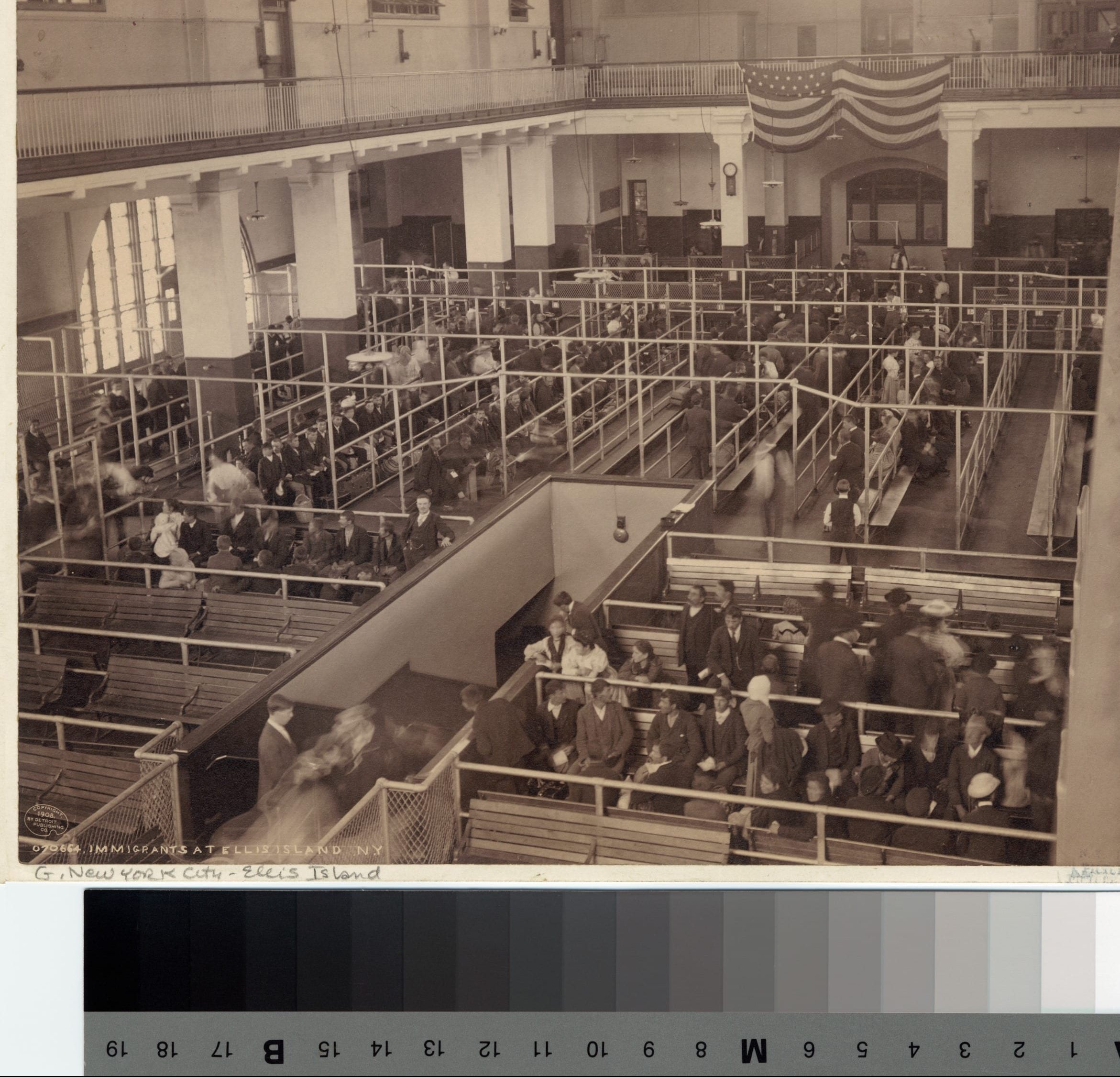

Once the Constitution was ratified, this debate over the nature of representation receded into the background. (However, Progressives in the early twentieth century returned to the idea of a more direct democracy, and were successful in making Congress more democratic. See, for instance, Progressive Democracy, chapters 12–13.)

Parties and the Structure of Power in Congress

Because the Constitution was vague about the rules and procedures that should govern the House and the Senate, two additional issues have influenced the development of Congress to the present day. Thus a second question these readings seek to address is Congress’s internal organization. The Constitution does not specify how the rules of Congress are to be set up; it merely says that each House shall make its own rules. But the manner in which the rules are set up determines who wields the power in Congress.

Thus, many of the primary sources after the ratification of the Constitution concern various rules governing debate, which bills can be sent the floor, what powers the committees will have, and so forth. These rules allocate power among various people in Congress—such as the leadership, the majority party as a whole, the committee chairs, etc. In terms of the distribution of power in Congress, there have essentially been four distinct periods with four distinct approaches.

In the first period, from 1790 to the middle of the 1800s, Congress was governed by collective deliberation among equal members, with weak leadership and no real committee structure. Attempts to limit debate, such as when Henry Clay tried to curtail the Senate filibuster in 1841 (see Debate on the National Bank Filibuster), were regarded as placing a “gag rule” on open debate enabling every member to participate in deliberations.

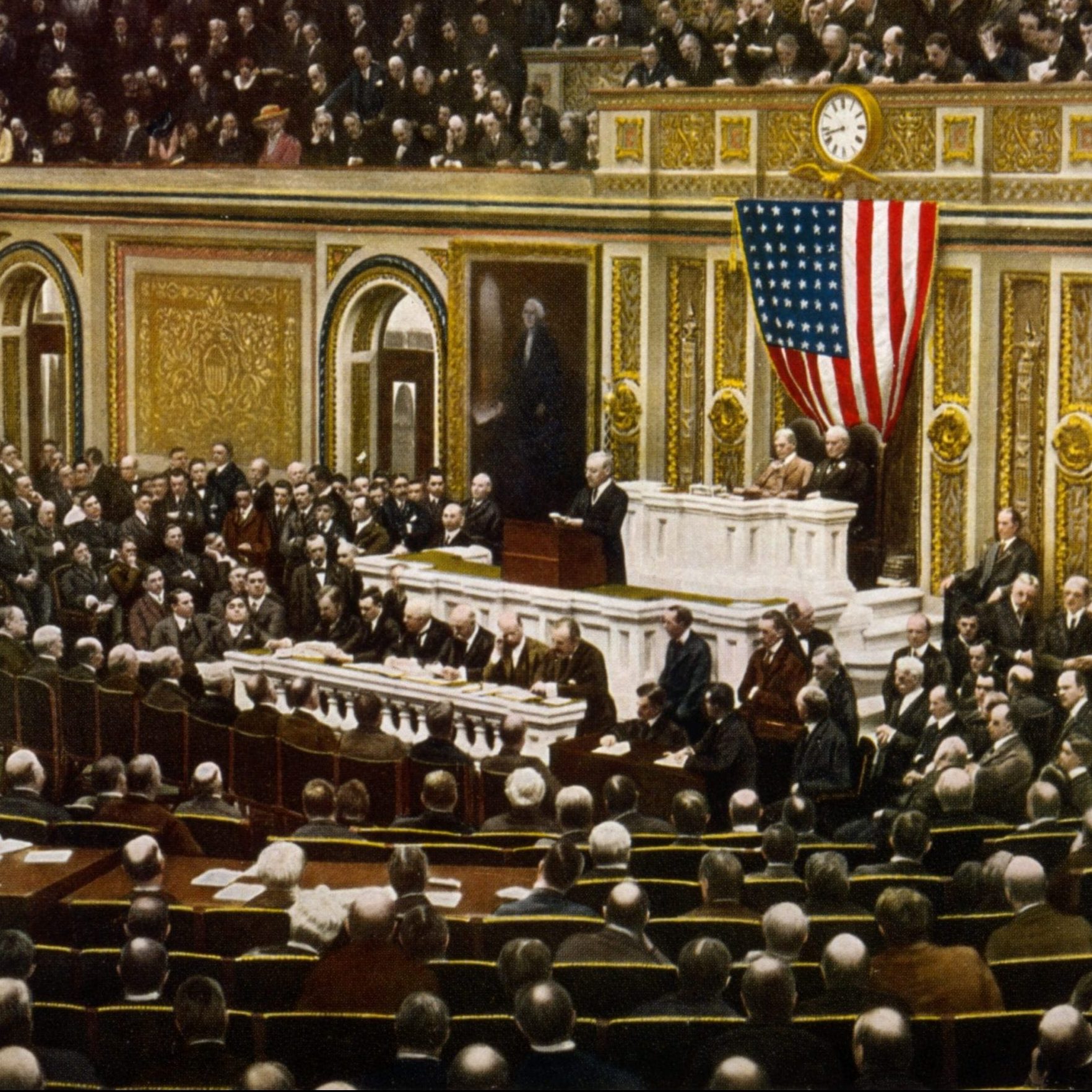

Following the Civil War, Congress entered a second period of strong party leadership, disciplining an emerging committee structure. In this period, the Speaker of the House and the leader of the majority party in the Senate held enormous power (see Constitutional Government in the United States for an account of how this occurred). This structure ensured party loyalty, which allowed the majority to impose an agenda and legislate on behalf of the national majority (see Rules of the House of Representatives and Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body).

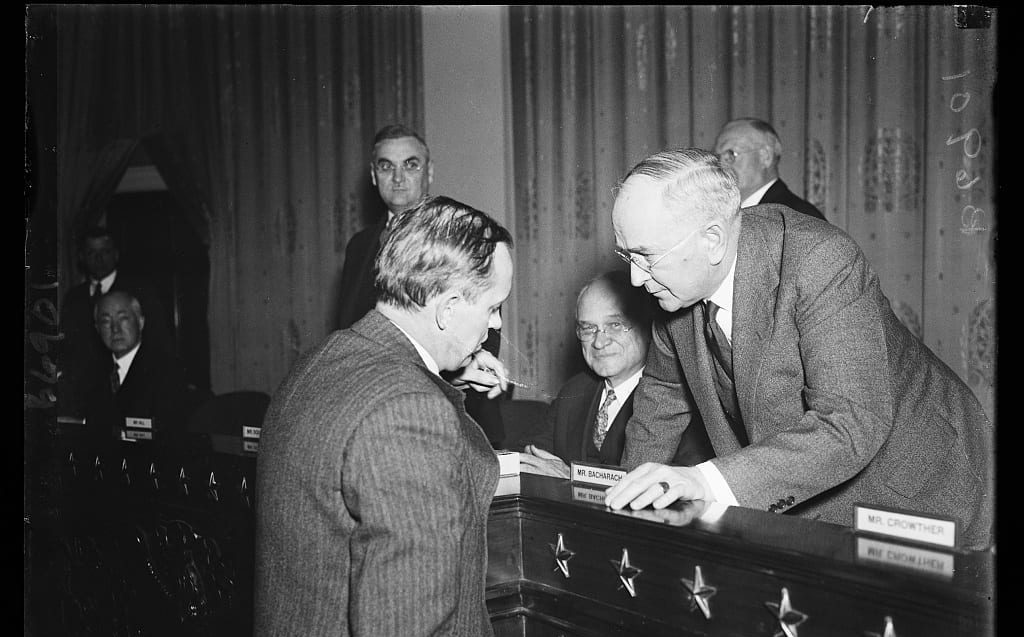

This second period ended in a shocking, St. Patrick’s Day revolt against the party leadership of Joseph Cannon (see The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress). Tired of taking orders from party leaders, and spurred by Progressive reformers who wanted a more democratic distribution of power in Congress (see Constitutional Government in the United States, Progressive Democracy, chapters 12–13, and Your Congress), members of the House voted to take away the power of the Speaker. The result was the third period of Congress—a period of committee-dominated government, in which committee chairs held the power.

This structure caused a great deal of concern in Congress, especially among Progressives, because the chairs were selected by seniority, and thus tended to be more conservative. During this period, from 1910–1974, there were repeated attempts to return power to party leaders and take power away from committee chairs, to make Congress as efficient as it was during the second period (see Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule and Debate to Expand the Rules Committee).

Since the 1970s, Congress has entered a fourth era, characterized by a moderate return of power to party leaders, but without the centralization of the second period. In this period, committees play less of a role in the process (see Reflections on the Republican Revolution and This is the People’s House: John Boehner’s First Remarks as House Speaker), which has deprived Congress of much of its expertise. Politics, rather than expertise, dominates much of what Congress does today.

In examining the four periods of Congress’s history, we are challenged to consider the merits and demerits of each model of Congress. The documents referenced above indicate, in the words of the reformers themselves, the advantages and disadvantages that people identified as they were debating adjustments to these rules. While seemingly arcane, these rules are critical to American constitutionalism because they affect the responsiveness, the efficiency, and ultimately the willingness of the Congress to use its legislative powers and therefore to preserve our republican form of government.

The Decline of Congress and the Rise of the President

The third and final theme in these documents, also debated consistently from the First Congress to today, has to do with Congress’s external relationship to the president. The legislative-executive relationship, and the balance of power between the two branches, has evolved dramatically since 1789. Although there are other issues that raise questions about the balance of power between Congress and the president, three issues are highlighted in these documents: Debates on the Legislative Branch) the president’s power to appoint and remove administrative officials (see A Debate on the President’s Removal Power: The Decision of 1789, Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson, Cato No. 5) the president’s power over legislation and Congress’s ability to delegate power to the president (see House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads, House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton, and INS v. Chadha), and Federal Farmer No. 7) the power to declare and wage war (see Debates on the Legislative Branch, Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War, Speech on the Constitutionality of Korean War, and Debate to Override President Richard Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution).

The first two of these questions address the balance of power between Congress and the president in domestic policy. Should Congress, the elected legislature, be the primary maker of policy through the writing of specific laws? Or should the president, the national representative, be the most important domestic policymaker, with Congress granting discretion to the executive branch controlled by the president?

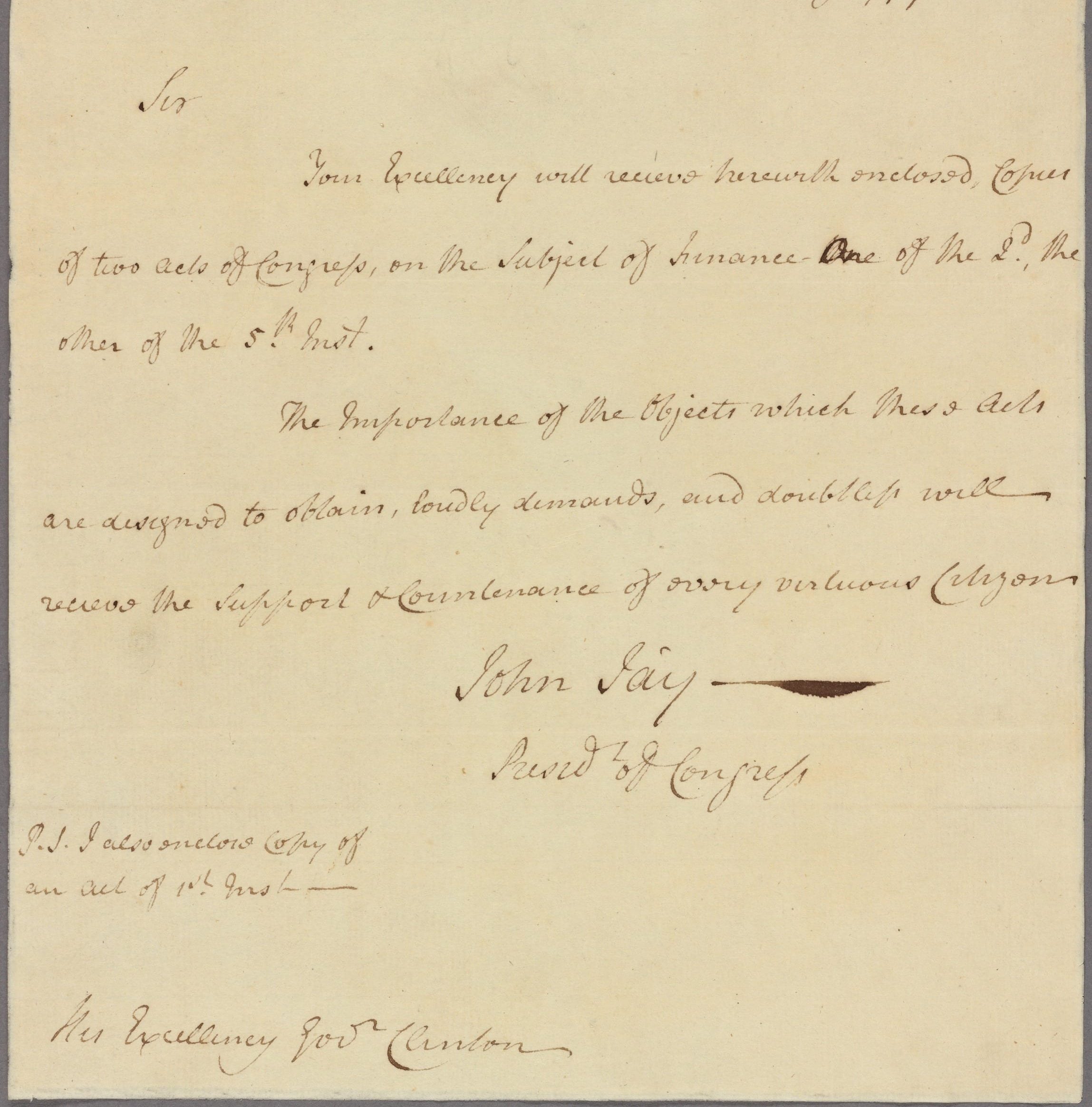

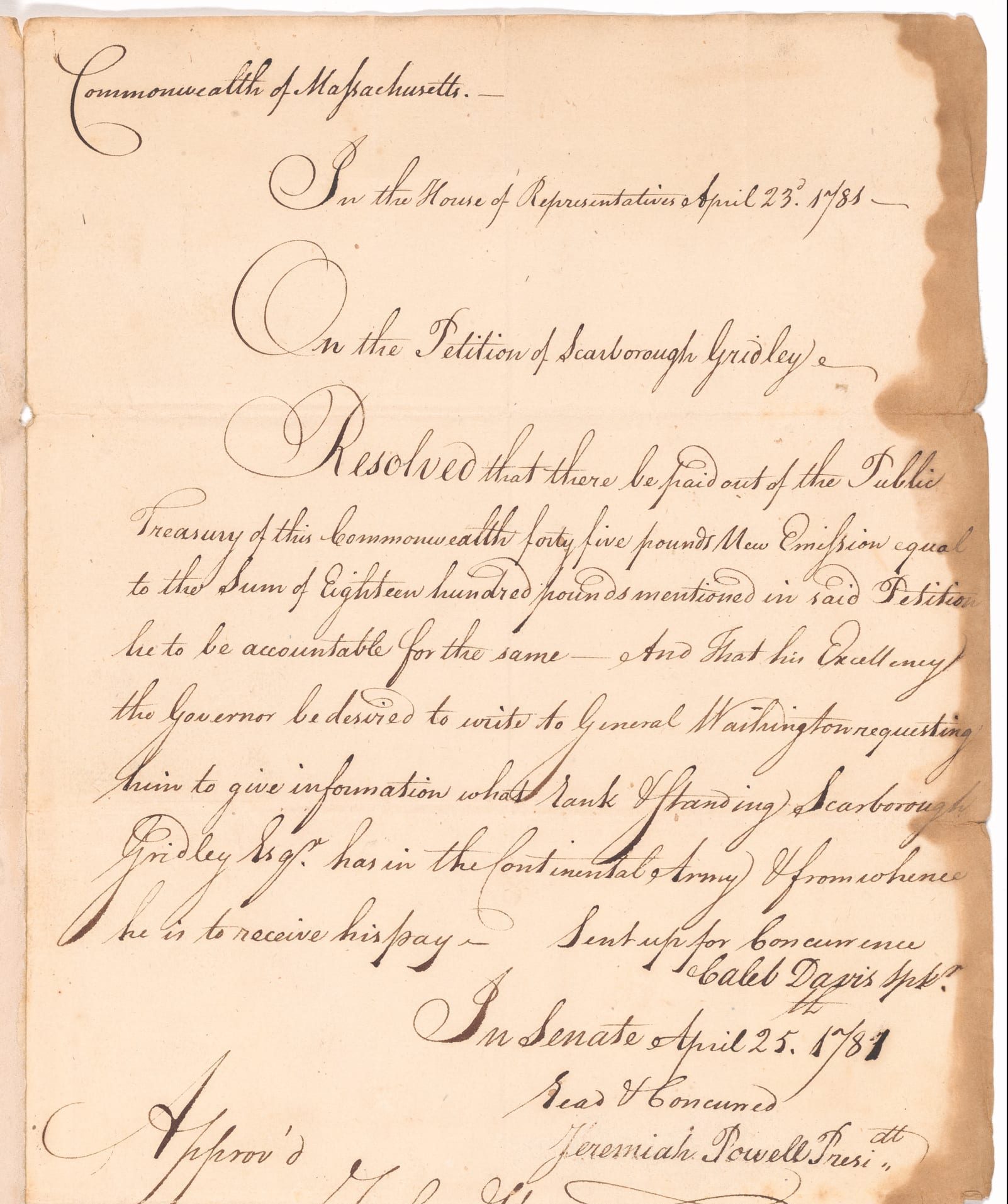

In the early years of the American republic, Congress acted as James Madison predicted when he said it would be an “impetuous vortex” (see Federalist No. 48). It wrote laws very carefully, addressing all of the details, so that the executive was merely carrying out its will (see especially House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads). The president had total control over administrative officials (see A Debate on the President’s Removal Power: The Decision of 1789), but those officials had little authority to make their own decisions. Their hands were tied by the law.

More recently, the president has emerged as a national policymaker because Congress has delegated more power and discretion to the executive branch. It has tried to keep control over these delegations, through things like legislative vetoes, but these have proven relatively ineffective (see INS v. Chadha).

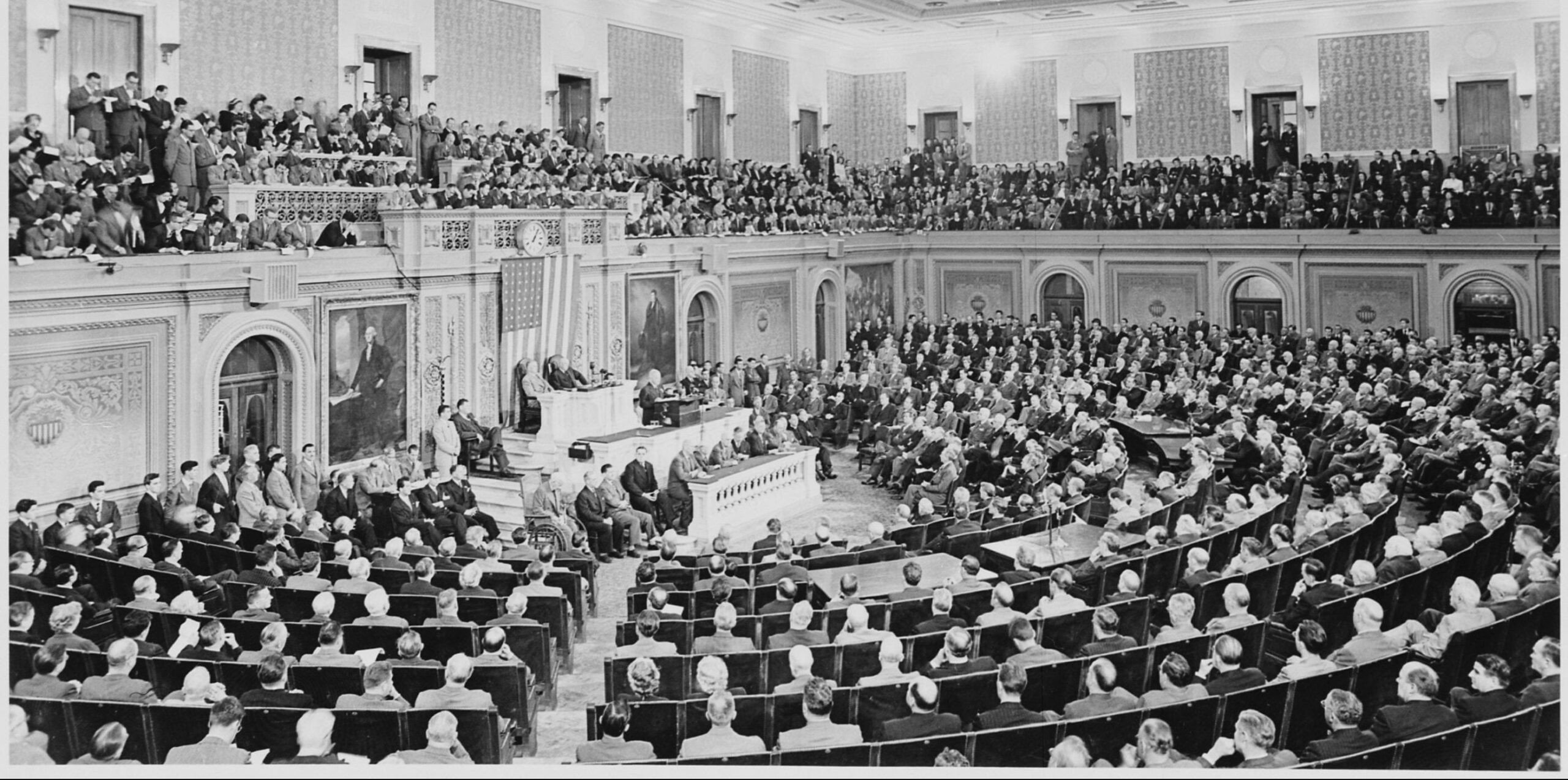

The same trend has occurred in foreign policy. Although presidents routinely involved the nation in military conflicts, without declarations of war by Congress (see Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War), the nature of these conflicts changed in the twentieth century (see Speech on the Constitutionality of Korean War). Now, presidents involve the nation in major military actions without declarations of war. Congress has attempted to reclaim the power to declare war (see Debate to Override President Richard Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution), but this too has proven ineffective.

Congress and the American Experiment

The American Founders famously committed themselves to an experiment to see if a nation could govern itself through the consent of the governed. This was a relatively new phenomenon at the time the nation was founded. We often take it for granted today. But the decline of public esteem for Congress should be cause for serious concern. If we do not understand how consent of the governed works, and how it should work, we risk losing it.

Teachers and their students have a critical role to play, therefore, in sustaining self-government by studying how it works in our Congress. Through careful examination of the principles and ideas in these documents, we become twenty-first century. Congress was once the great achievement of the American Constitution. A knowledgeable and engaged citizenry can make it so again.

Many of the debates in this book have been transcribed from the Congressional Record for the first time, and I am grateful to Allison Brosky for her assistance in transcribing them. I am also grateful to Grant Reinicke for valuable assistance in drafting and revising the document introductions. An anonymous reader for Ashbrook Press pointed me to important documents that I had not considered for the collection. Finally, I am grateful to the B. Kenneth Simon Center for Principles and Politics at The Heritage Foundation, whose sabbatical fellowship enabled me to complete this volume.

Joseph Postell

The Nature of Representation in Congress

- Debates on the Legislative Branch

- Cato No. 5

- Federal Farmer No. 7

- Federal Farmer, No. 11

- Brutus No. 16

- Federalist No. 10

- Federalist No. 35

- Federalist No. 52

- Federalist No. 62

- Federalist No. 63

- Progressive Democracy, chapters 12–13 (excerpts)

- Your Congress

Congress and the Separation of Powers

- Federalist No. 48

- Federalist No. 51

- A Debate on the President’s Removal Power: The Decision of 1789

- House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton

- Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson

- Cabinet Government in the United States

- Politics and Administration

- Constitutional Government in the United States

Parties, Process, and the Structure of Power in Congress

- Federalist No. 55

- Federalist no. 58

- Debate on the National Bank Filibuster

- Congressional Government

- Rules of the House of Representatives

- Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body

- The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon

- Speech on Party Leadership in Congress

- Your Congress

- Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule

- Debate to Expand the Rules Committee

- Reflections on the Republican Revolution

- This is the People’s House: John Boehner’s First Remarks as House Speaker

The Delegation of Lawmaking Power to the Executive

- House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads

- House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton

- Politics and Administration

- Progressive Democracy, chapters 12–13 (excerpts)

- INS v. Chadha

Congress and the Presidency in War Powers

1. Debates on Congress at the Constitutional Convention, 1787

1. What arguments were made on behalf of indirect election of U.S. senators by state legislatures? Are those arguments sound? How did delegates such as James Wilson and James Madison respond to these arguments, and what does their response reveal about their view of republican government? What were the arguments for and against annual elections for legislators? Would you prefer annual elections for Congress today?

2. How do the arguments of delegates such as Elbridge Gerry and Roger Sherman, on the need for shorter term lengths and rotation in office, foreshadow the views of the Anti-Federalists such as Cato, Federal Farmer, and Brutus (Cato No. 5, Federal Farmer No. 7, and Federal Farmer, No. 11)? Why did delegates at the Convention refuse to give the power to declare war to the president, and did later Congresses follow their example (Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War and Debate to Override President Richard Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution)?

2. Cato No. 5, November 22, 1787

1. What effect will annual elections have on citizens, according to Cato? Why will frequent elections have this effect? What does Cato mean when he says that the people only enjoy “virtual representation” in the Senate?

2. How did James Madison respond to Cato’s argument for annual elections in Federalist 52? Does Madison disagree that frequent elections are important? Why does Madison argue, contrary to Cato, that two-year term lengths are acceptable?

3. Federal Farmer No. 7, December 31, 1787

1. According to Federal Farmer, what role do persuasion and force play in making government effective? What is the difference between the two? Why do governments require both? Which of the two is a preferable foundation for a free society? Why, in Federal Farmer’s view, will this government rely upon the opposite foundation? Why is it so important for a legislature to sympathize with, and have the sympathy of, the people? Which arrangements ensure that a legislature acquires this sympathy?

2. Does James Madison disagree with Federal Farmer that the representatives must be connected to the people and sympathize with them (Federalist No. 52)? Does Madison believe that the government will not reflect the wishes of the people (Federalist No. 10)? How do Federal Farmer and Madison differ in their predictions for what kind of person will be elected to Congress under the Constitution (Federalist No. 63)?

4. Federal Farmer No. 11, January 11, 1788

1. Why does Federal Farmer insist upon the recall of senators? What effects will recall have upon representatives, and why is this desirable? Why does Federal Farmer object to the number of representatives? Why does Federal Farmer propose “rotation” in office? What effect will this have on representatives? In general, where does Federal Farmer believe abuse of power comes from in a republic: the people, or their rulers?

2. Would James Madison support the idea of recalling senators, based on his description of responsibility in a representative in Federalist No. 63? How would recalling senators, and reducing the length of their tenure in office, affect their performance, in Madison’s view in Federalist No. 62 and Federalist No. 63?

5. Brutus No. 16, April 10, 1788

1. Why does Brutus argue that terms for senators are too long? What happens to people, according to Brutus, who are not subject to frequent elections? Why does Brutus propose a rotation in office? What does Brutus predict will happen to senators once they enter into office? How will their incumbency affect their reelection bid?

2. How would James Madison respond to Brutus’s argument about the term lengths of senators, given his argument in Federalist No. 63? Which side has the better of the argument? What are the different virtues in senators that Brutus and Madison want to cultivate?

6. Federalist No. 10, November 22, 1787

1. What is the problem of faction, and how does the Constitution break and control the violence of faction? What role does this suggest for Congress? What is a faction? What effect will faction and party have in Congress’s deliberations? How does representation affect the way public opinion influences Congress? Does Madison suggest in this essay that there are limits to the principle of representation? How accountable to their constituents does James Madison expect members of Congress to be in this essay?

2. Is there a tension between Madison’s view of representation in this essay and his view in other essays, especially Federalist No. 52 and Federalist No. 63? When you look at these three essays as a whole, does Madison expect representatives to reflect the views of their constituents, to refine and filter those views, or a mixture of both?

7. Federalist No. 35, January 5, 1788

1. Why does Alexander Hamilton argue against the notion of an “actual representation of all classes of the people?” How, in Hamilton’s prediction, will the various interests of the nation decide upon the people who will represent their views? Why does Hamilton think that all of the various interests will be considered when representatives are making decisions in Congress? What encourages representatives to advance the interests of their constituents, even if they are not from the same occupation?

2. Does Hamilton anticipate that the different economic classes will all receive representation in Congress? How is his prediction similar to James Madison’s prediction in Federalist No. 10? Why do they both predict that interests, rather than classes, will be the basis for representation in Congress?

8. Federalist No. 48, February 1, 1788

1. Why does James Madison call the legislative power the “impetuous vortex?” Why is this a problem? Why is legislative power the most dangerous power in a republican form of government? How does a republic differ from a monarchy or an aristocracy in this respect? What specific features of legislative power make it so dangerous?

2. Is Madison correct about the dominance of the legislative branch in a republic, or is the executive more likely to be dominant? What does Congress’s conduct after the Civil War (Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson) reveal about this question? On the other hand, does the executive have the upper hand in certain matters, such as war and foreign affairs (Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War, Speech on the Constitutionality of Korean War, and Debate to Override President Richard Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution)?

9. Federalist No. 51, February 6, 1788

1. What are the two main prerequisites for maintaining three independent branches of government? How does this affect the way in which each branch is selected and supported financially? Which branch in particular creates the need for checks and balances? How is that branch checked? What is the difference between constitutional means and personal motives, and how is each provided for in the Constitution? How is the executive strengthened, and with which part of Congress is it connected?

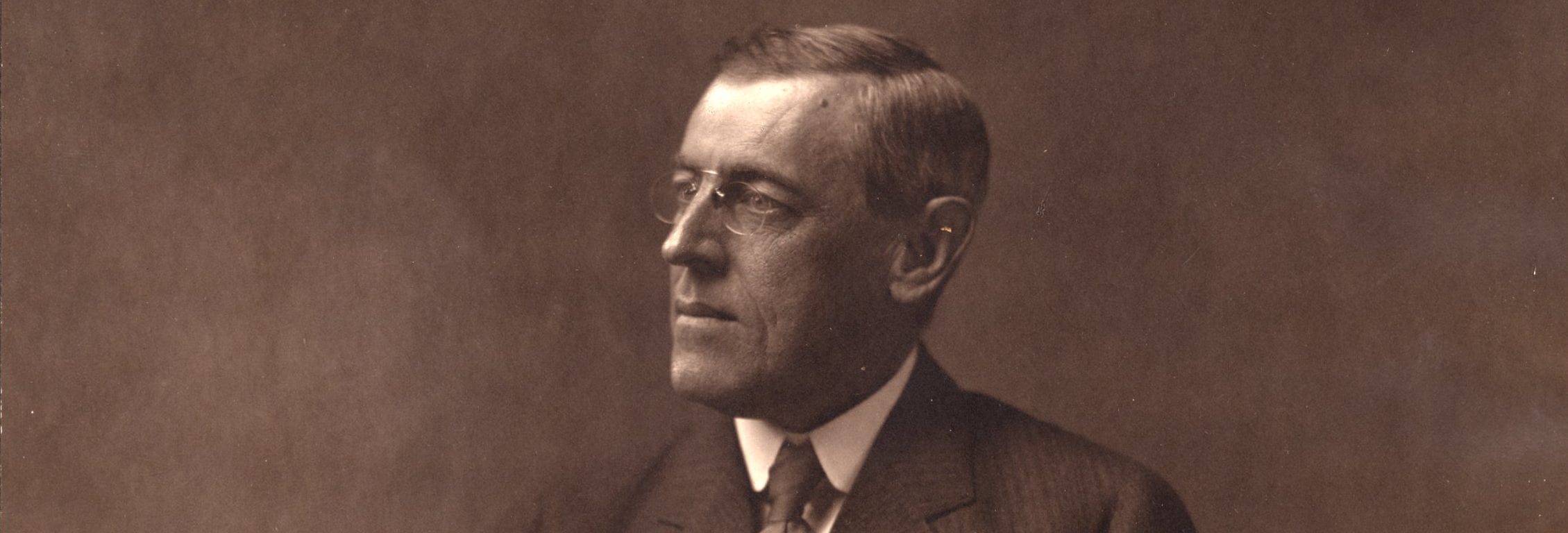

2. Why did Woodrow Wilson and Frank Goodnow differ from James Madison in his view of the separation of powers (Cabinet Government in the United States, Politics and Administration, and Constitutional Government in the United States)? Why did Wilson believe that the separation of powers was a problem, and how did he seek to undermine the separation of powers? How might Madison have responded to Wilson’s critique of separation of powers, and his alternative proposals?

10. Federalist No. 52, February 8, 1788

1. What qualifications are required for voting in elections for the House of Representatives? Why is this an important aspect of republican government? How does James Madison describe these qualifications? What restrictions are placed on the right to vote for members of the House, or to run for a seat in the House? How does Madison describe the term length for members of the House, and what kind of relationship does this create between members of the House and the people they represent?

2. Does Madison essentially agree with Anti-Federalists such as Cato No. 5 and Brutus No. 16 about the importance of frequent elections, at least with regard to the House? What is the difference between the way Madison describes the term lengths of the House in this essay and his discussion of Senate term lengths in Federalist 62 and 63?

11. Federalist No. 55, February 13, 1788

1. Why is the number of representatives such an important consideration, according to James Madison? What defects arise from increasing the number of representatives? What defects arise from having too few representatives? Today, many have proposed increasing the number of representatives in the House to 1,000. How would Madison likely respond to such proposals?

2. How might Federal Farmer respond to Madison’s argument about the problems of too many representatives? What are the benefits and the drawbacks of each side’s argument?

12. Federalist No. 58, February 20, 1788

1. Why is James Madison so confident that the House will increase rapidly in size? How does he respond to the objection that the small states, through the Senate, will obstruct reapportionment efforts? What does this indicate about the balance of power between the House and the Senate? What happens to legislative assemblies that grow too large, according to Madison? Why should we guard against increasing the size of the House too greatly?

2. How might Federal Farmer respond to Madison’s argument about the problems of too many representatives? What are the benefits and the drawbacks of each side’s argument?

13. Federalist No. 62, February 27, 1788

1. On what grounds does James Madison defend the increased requirements for serving in the Senate? What does this indicate about the intended difference between House representatives and senators? Does Madison defend the indirect election of senators, or the allocation of an equal number of senators to each state? What argument does he offer on behalf of these two provisions? What is the chief purpose of the Senate, and how does Madison connect that chief purpose to the term length and number of senators? What dangers or inconveniences arise from instability in the laws?

2. How would Brutus respond to Madison’s arguments in this essay, based on his discussion of the Senate in Brutus No. 16? What is the main difference between the way Brutus and Madison conceive of the Senate—especially the kind of representation that the Senate is supposed to contain?

14. Federalist No. 63, March 1, 1788

1. What does James Madison mean when he refers to the Senate’s “responsibility” to the people? What is so “paradoxical” about connecting responsibility to longer term lengths?

2. How does Madison’s definition of responsibility differ from that of Brutus No. 16? Whose definition of a responsible government is more compelling? What are the strengths of each side’s definition?

15. The Decision of 1789, May-July 1789

1. What are the four different positions that emerge regarding whether the president has the constitutional authority to remove executive branch officials? What are the arguments for each position? Which position ultimately prevails, and why? Is the debate decisive? What value does the debate possess as an indicator of the Constitution’s meaning on the power to remove officers?

2. Compare the reasoning of the Congress in the Decision of 1789 to Congress’s treatment of Andrew Johnson in Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson. What does this suggestion about the power struggle between Congress and the president after the Civil War? Which side was more powerful? Does Congress’s treatment of Johnson confirm James Madison’s analysis of legislative power in Federalist No. 48 and Federalist No. 51?

16. House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads, 1791

1. Why did some members of Congress object to delegating the power to designate post roads to the president? How did Reps. Samuel Livermore, Thomas Hartley, and John Page connect this requirement to the issue of voting rights and republican government? What did Rep. Sedgwick say in reply to them? What does this debate indicate about the challenge of distinguishing between legislative and executive power, and the difficulty of enforcing the requirement that laws are only enacted by Congress?

2. How are the concerns of members in this debate, about giving up too much power to the executive, linked to their objections to Alexander Hamilton’s influence (House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton)? Is there a difference between delegating the power to designate post roads and authorizing the treasury secretary to send proposals to Congress? If so, which one is legitimate, and which one is problematic?

17. House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton, 1792

1. Why did Rep. John Francis Mercer object to Congress directing the secretary of the treasury to report a plan for reducing the federal debt? Why did he argue that the House’s responsibility to legislate is incommunicable, and how did he extend that principle to this subject? How did Rep. William Loughton Smith respond to this argument? What did James Madison ultimately conclude to be the rule on this question? If you were a member of Congress participating in this debate, whose argument would you have agreed with and why? What concerns would motivate you on either side of the question?

2. What is the role of the executive in the legislative process, as debated in the discussion over giving the president the power to create post roads (House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads) and this discussion? Is there anything the legislature can do to give the executive the power to originate proposals, but retain the final word on those proposals? How did the Supreme Court’s ruling in INS v. Chadha affect this question?

18. Alexander Hamilton, Pacificus No. 1, June 29, 1793

1. How does Alexander Hamilton describe the nature and purpose of Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation? What did the proclamation do? Understood this way, why was it compatible with the Constitution, which authorizes Congress to declare war? Why was it compatible with our treaty with France? What is Hamilton’s view of the amount of executive power given to the president by the Constitution?

2. What is the main difference between Hamilton’s and James Madison’s views on executive power, in Pacificus No. 1 and Helvidius Nos. 1, 2, and 4? What is the nature of a declaration of neutrality? Is it different from a declaration of war? Are all of these declarations merely declaring the existing state of affairs, or creating a new state of affairs? What do the members of Congress have to say about this in Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War? Are any of Hamilton’s arguments contradicted by Congress’s debate over the War Powers Resolution (House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton)?

19. James Madison, Helvidius Nos. 1, 2, and 4 (excerpts), August-September 1793

1. Why is the power to declare war, in James Madison’s view, a legislative and not an executive power? What powers over foreign policy does the president have, according to Madison? Is there anything in the Constitution that suggests the executive should have the power to declare or initiate war? What is so dangerous about giving the executive the power to declare war?

2. Why is it so important that the legislature control the power to declare war? Do Madison’s arguments in this essay align with the statements made about war power at the Constitutional Convention (Debates on the Legislative Branch)? Do they align with the arguments made in Congress much later, when discussing the War Powers Resolution (Debate to Override President Richard Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution)?

20. Senate Debate on National Bank Filibuster, 1841

1. Why does Henry Clay argue that attempts to delay the business of the Senate replace “contests of intellect only” with “brutal physical force”? What does this debate reveal about the relationship between deliberation and the right of the majority to pass legislation? What arguments do the defenders of unlimited debate advance for their position?

2. How is the debate between allowing unlimited debate and the need for majority rule, in this case, similar to later discussions about the power of the Speaker of the House during the Revolt of 1910 (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress) and the power of committee chairs and the Rules Committee during the twentieth century (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule and Debate to Expand the Rules Committee)?

21. Senate Debate on the Declaration of War Against Mexico, May 1846

1. Was President James K. Polk’s message to the Congress, asking for a recognition that war already exists, out of line? In other words, was Sen. John C. Calhoun right to distinguish between hostilities and war, and to conclude that war could never exist unless Congress declared it to exist? Can war exist even if Congress does not declare it? If so, does that mean that any and all hostilities between nations create a state of war, or as Sen. William S. Archer argues, are there some hostilities that don’t amount to war? How is the line to be drawn that separates war from hostility, in a way that leaves Congress in charge of its power to declare war?

2. Do the arguments about war versus hostility reappear, in different form, in the debate over the Korean War a century later (Speech on the Constitutionality of Korean War)? Is there a difference, as Sen. Karl Mundt argues, between the scope of the hostilities that sparked the Mexican-American War and the scope of the hostilities that characterized the Korean War? If so, does that mean that the Korean War was entered into unconstitutionally?

22. Articles of Impeachment Against Andrew Johnson, March 7, 1868

1. Which Act of Congress did Andrew Johnson violate, and how did this lead to the attempt to remove him from the presidency? What other actions did Johnson take to prompt Congress to begin the impeachment process? Was it inappropriate of Johnson to appeal to the people in an attempt to defend himself from Congress’s attacks on him? Is this something presidents do today?

2. Was Congress’s efforts to limit Johnson’s removal power consistent with the Decision of 1789 (A Debate on the President’s Removal Power: The Decision of 1789)? Did Congress overstep its constitutional authority when it passed the Tenure of Office Act?

23. Woodrow Wilson, Cabinet Government in the United States, 1879

1. Why did Woodrow Wilson think that Congress was not responsible to the people for the legislation that it passed? What prevented Congress from being held accountable, and why did this feature undermine deliberation and discussion in Congress? How did Wilson propose to solve this problem? How would the Constitution need to be changed to bring about Wilson’s solution?

2. How does Wilson’s vision for the future of Congress, in this essay, contrast with his later proposals for a stronger presidential role in leading Congress (Congressional Government and Constitutional Government in the United States)? Which set of proposals from Wilson would be easier to fit within the constitutional system? Which set of proposals do we tend to follow today? How do all of these proposals undermine the separation of legislative and executive power advocated by James Madison and the other Framers (Federalist No. 48 and Federalist No. 51)?

24. Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government, 1885

1. Why does Woodrow Wilson lament the fact that, in his words, “Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work”? How does that affect the accountability of Congress? How does Wilson propose to reform Congress to make its committee system more accountable? What is the role of debate and discussion in Congress, in Wilson’s view? What goods do deliberation and discussion provide for our political system?

2. How would Thomas Brackett Reed respond to Wilson’s call for more deliberation and discussion in Congress (Rules of the House of Representatives and Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body)? Is there a limit to how much discussion and deliberation should take place? At some point, does the deliberative function of Congress need to give way to the need for efficiency in the passage of laws (Debate on the National Bank Filibuster)? How would Wilson have viewed the debate over the power of committees in the twentieth century (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule)?

25. Thomas Brackett Reed, Rules of the House of Representatives, March 1889

1. According to Thomas Brackett Reed, what has happened to the rules of the House of Representatives in the years preceding the publication of his article? Why has this change in the rules, and the way they are used, come about? What political factors have caused these changes? How does Reed propose to remedy the problems associated with these changes, and what theory of republican government informs his views on how the House should be run?

2. How does Reed’s arguments about majority rule affect the role of party leadership in the House of Representatives (see The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress)? How does party leadership, in the view of Reed and the defenders of parties, enable Congress to be more responsible to the majority of the American people?

26. Thomas Brackett Reed, Articles in the North American Review, 1889–1891

1. What is Thomas Brackett Reed’s chief complaint about the way the House operates in “Obstructions in the National House?” What is the chief purpose of a legislative body, according to Reed, and how do the rules of the House undermine Congress’s ability to perform that chief function? Why does Reed argue that changing the House’s rules is something we should not fear?

2. How does Reed’s view of the purpose of a legislative body differ from that of John C. Calhoun and others in the debate over the Senate’s filibuster (Debate on the National Bank Filibuster)? In your view, which side has the better argument? Is there an arrangement that would balance the concerns of both Reed and Calhoun, preventing obstruction but allowing everyone to participate in lengthy debate?

27. Frank Goodnow, Politics and Administration, 1900

1. According to Frank Goodnow, what is the difference between politics and administration? What new division of powers does Goodnow seek to replace the old separation of powers with? How will this affect the way Congress functions in the twentieth century and beyond? How does Goodnow describe the role of Congress in supervising the administrative branch of government?

2. What common themes are present in both Goodnow’s and Woodrow Wilson’s critique of the separation of powers (Constitutional Government in the United States)? How would Goodnow’s vision for Congress advance the ideal Congress that Wilson outlines at the end of Congressional Government? How would Congress’s structure and activity change as a result of decreased lawmaking and increased oversight? Is this what happened in the twentieth century (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule and Debate to Expand the Rules Committee)?

28. Woodrow Wilson, Constitutional Government in the United States, 1908

1. Why does Woodrow Wilson criticize the separation of powers and the theory of checks and balances? How does his vision for government differ from the basic theory of checks and balances? What are the benefits of his vision of government as an organic unity? What are the dangers? How has Congress evolved to develop its own internal, party leaders, according to Wilson? What were the major events that contributed to the emergence of party leadership? Why does Wilson want a different kind of leadership, and where is that leadership going to come from?

2. How does Wilson theory of political leadership differ from the idea of party leadership advanced by Thomas Brackett Reed (Rules of the House of Representatives and Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body)? How would Wilson have evaluated the arguments in the Revolt of 1910 (Speech on Party Leadership in Congress)? Would Wilson have applauded the end of congressional leadership, as it opened the door for presidential leadership?

29. The Revolt of 1910, March 17–19, 1910

1. What charge to Joseph Cannon’s opponents, such as Reps. Miles Poindexter, John Nelson, and Otto Foelker, make against the powers of the Speaker? How does the Speaker’s authority undermine representative government, in the view of his opponents? On what grounds do Cannon’s supporters defend the power of the Speaker and the Rules Committee? To whom is the Speaker accountable, in their view? Why does Rep. Jacob Sloat Fassett defend the idea of partisanship and party control of the House? How does party control facilitate majority rule and responsibility to the people?

2. How does the idea of party-based representation, focused on national party priorities and national views, conflict with the interest-based model of representation advanced by James Madison in Federalist 10? How did the weakening of the Speaker’s power lead to powerful committees later in the twentieth century, and what were the problems with strong committees (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule )?

30. Speech of Joseph Cannon, March 19, 1910

1. On what grounds does Speaker Joseph Cannon defend his leadership and rule over the House of Representatives? Why does Cannon assert that there is no true majority in the House of Representatives, as evidenced by the decision to strip him of power? What does this indicate about Cannon’s theory of majority rule?

2. In what ways is Cannon’s argument for strong party leadership in Congress similar to the arguments made by Thomas Brackett Reed (Rules of the House of Representatives and Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body)? How is his view of the role of political parties similar to the views of Jacob Sloat Fassett during the Revolt of 1910 (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon)?

31. Herbert Croly, Progressive Democracy, 1914

1. In Herbert Croly’s view, why did America need to rely on representation rather than pure or direct democracy in the 1700s? What changed circumstances make direct democracy more feasible in the 1900s? How should government be made more directly democratic, in his view? How should a direct democracy, if it is progressive, lead to a stronger government and especially a stronger administrative branch?

2. How does Croly seek to reconcile the tension between more direct democracy and aggrandizement of administrative agencies? Is his solution different than, or similar to, the vision offered by Frank Goodnow (Politics and Administration)? Is Croly’s version of direct democracy the same as that of Anti-Federalists such as Federal Farmer and Brutus (Federal Farmer No. 7, Federal Farmer, No. 11, and Brutus No. 16)?

32. Lynn Haines, Your Congress, 1915

1. Why does Lynn Haines believe that, in spite of the Revolt of 1910, Congress is still beholden to parties and party bosses? What is his proposed solution to the problem of party rule? How should Congress be reformed, in his view, to be made more accountable to the people? What would his alternative Congress look like?

2. How does Haines’ reconstructed Congress use committees in a different way than Congress operated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Congressional Government and Constitutional Government in the United States)? Should committees be more autonomous, as Haines argues, or more accountable to the majority, as other reformers argued throughout American history (Debate to Expand the Rules Committee)? Does Haines’ vision for Congress sacrifice all of the benefits of the separation of powers and bicameralism advanced in the Federalist (Federalist No. 48, Federalist No. 51, and Federalist No. 62)?

33. House Debate on the Repeal of the 21-Day Rule, January 1950

1. Why does Rep. Adolph J. Sabath oppose the repeal of the 21-day rule? Why was the rule necessary, in his view? Why does Sabath argue that this repeal will return power to the leadership and restore “Cannonism”? Why do Sam Rayburn and Ray Madden suggest that the 21-day rule has made the House more democratic, and that repealing it will make the House undemocratic? Why do Reps. Edward Eugene Cox and Clarence Brown suggest that keeping the 21-day rule opens the door to “socialistic” legislation by taking the “governor” off of legislation? What does this debate indicate about the power of the Rules Committee during this period, and the kinds of people who served as the chair of that committee?

2. How does Rayburn’s argument resemble the same arguments deployed by Joseph Cannon and his defenders during the 1910 Revolt (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress)? What does this indicate about the power of committee chairs during the twentieth century and the effect of powerful chairs on Congress’s ability to represent the people?

34. Senate Debate on Constitutionality of the Korean War, May 1951

1. According to Sen. Karl Mundt, why did the United States intervene in the Korean War? What authority sent the troops to Korea? Why, in his view, is this intervention different from any other military intervention launched by the president in the past? Does Sen. Mundt suggest any solution or remedy to the problem of a presidentially initiated war?

2. How is the Korean War similar to, and how is it different from, the military conflict that began the Mexican-American War (Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War)? Does the Korean War violate the division of war power between Congress and the president that was established at the Constitutional Convention (Debates on the Legislative Branch)?

35. House Debate to Expand the Rules Committee, 1961

1. Why do supporters of packing the Rules Committee, such as Reps. James William Trimble and Sam Rayburn, justify the need to increase the number of members of the Rules Committee? What is their end goal, in terms of changing how the House operates? How does Rep. Howard W. “Judge” Smith, as well as his supporters, defend the role of the Rules Committee? Are their arguments for delaying the legislative process, in order to filter out bad proposals, convincing?

2. How do the arguments of Rep. Trimble and Rep. Rayburn, about the need for the majority to be able to work its will, resemble the same arguments of Thomas Brackett Reed and Joseph Cannon for party leadership (Rules of the House of Representatives, Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body, and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress)? Does this mean that there was some wisdom in the earlier attempts to give party leaders power over otherwise independent committees? In what ways are the arguments for packing the Rules Committee similar to those for the 21-day rule (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule)? What does this reveal about the tension created by the decision to weaken party leadership in the Revolt of 1910 (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon)?

36. Debate on Overriding President Richard M. Nixon’s Veto of the War Powers Resolution, November 1973

1. Why do Sen. Thomas Eagleton and Rep. James R. Grover Jr. oppose the War Powers Resolution? Why does he think it will actually have the opposite effect as it intends – i.e., why will it actually increase rather than diminish the power of the president? How is his opposition to the resolution different from Sen. Barry Goldwater’s?

2. How did supporters of the resolution, such as Sen. Jacob Javits and Reps. Clement J. Zablocki and William Broomfield, use the Constitution to justify it on constitutional grounds? Are their arguments about the Constitution’s division of war powers accurate, in light of the record at the Constitutional Convention (Debates on the Legislative Branch)? Are Sen. Eagleton and Rep. Grover right that the resolution actually authorizes unconstitutional presidential action, in light of earlier debates over conflicts initiated by the president (Debate on the Constitutionality of the Mexican War and Speech on the Constitutionality of Korean War)?

37. INS v. Chadha, 1983

1. What is a legislative veto and what is the constitutional problem with it, according to Chief Warren E. Justice Burger? Why is the legislative veto unconstitutional, in his view, even if it makes the political process operate more efficiently and conveniently? Why does Justice Byron “Whizzer” White disagree with the majority opinion in this case? How, according to White, does the legislative veto keep administrative officials accountable to Congress, and why is that goal consistent with the vision of the American Founders?

2. How does the legislative veto deal with the problem of delegation of legislative power in a different way than earlier efforts to prevent delegation in the first place (House Debate on the Establishment of Post Roads and House Debate on the Influence of Alexander Hamilton)? How would Progressives such as Frank Goodnow, who wanted politics and administration to remain separate (Politics and Administration), view the legislative veto? How would Herbert Croly have treated the legislative veto, in light of his view that a progressive democracy needs to empower both the legislature and the power of administrative agencies (Progressive Democracy, chapters 12–13 (excerpts))?

38. Richard Armey, Reflections on the Republican Revolution, 2005

1. How does Majority Leader Richard Armey describe the power structure in the House of Representatives when the Republican Party became the majority in 1995? What was the relationship between party leadership and committee chairs? What effect did committee chairs have on the way the House conducted its business, and the kinds of policies the House enacted? How did Speaker Newt Gingrich attempt to alter that power structure?

2. In what way is the struggle between party leaders and committee chairs during the 1990s similar to the struggles over the extent of party leadership throughout the twentieth century (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon, Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule, and Debate to Expand the Rules Committee)? What was different about the struggle between party leadership and committee chairs during the 1990s?

39. John Boehner, This is the People’s House, 2011

1. How does Speaker John Boehner describe his new vision for how the House of Representatives should operate? Why does he think it is better for the House to operate in this way? What are the likely consequences of opening the House up for more debate and minority party participation? Which rules will change, and how will they change, to implement Boehner’s vision?

2. How does Boehner’s vision for the House of Representatives, with its open rules and minority party participation, differ from the vision of a party-controlled House offered by Thomas Brackett Reed and Joseph Cannon (Rules of the House of Representatives, Obstructions in the National House and A Deliberative Body, and Speech on Party Leadership in Congress)? How does it differ from the vision for majority rule advanced by Henry Clay (Debate on the National Bank Filibuster)? How does Boehner respond to the notion that this will make the House operate less efficiently and stymie the will of the majority? How does Boehner’s proposal to rely on committees and an open process resemble the arguments of twentieth-century reformers who sought to reform the Rules Committee (Debate on repeal of the 21-day rule and Debate to Expand the Rules Committee)? How does it resemble the reformers who sought to overthrow Cannon (The Revolt of 1910 Against Speaker Joseph Cannon)?

Caro, Robert A. Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate. New York: Knopf, 2002.

Fenno, Richard. Congressmen in Committees. Boston: Brown & Little Co., 1973.

Fenno, Richard. Home Style: House Members in Their Districts. Boston: Brown & Little Co., 1978.

Mayhew, David. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.