Introduction

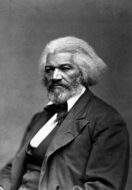

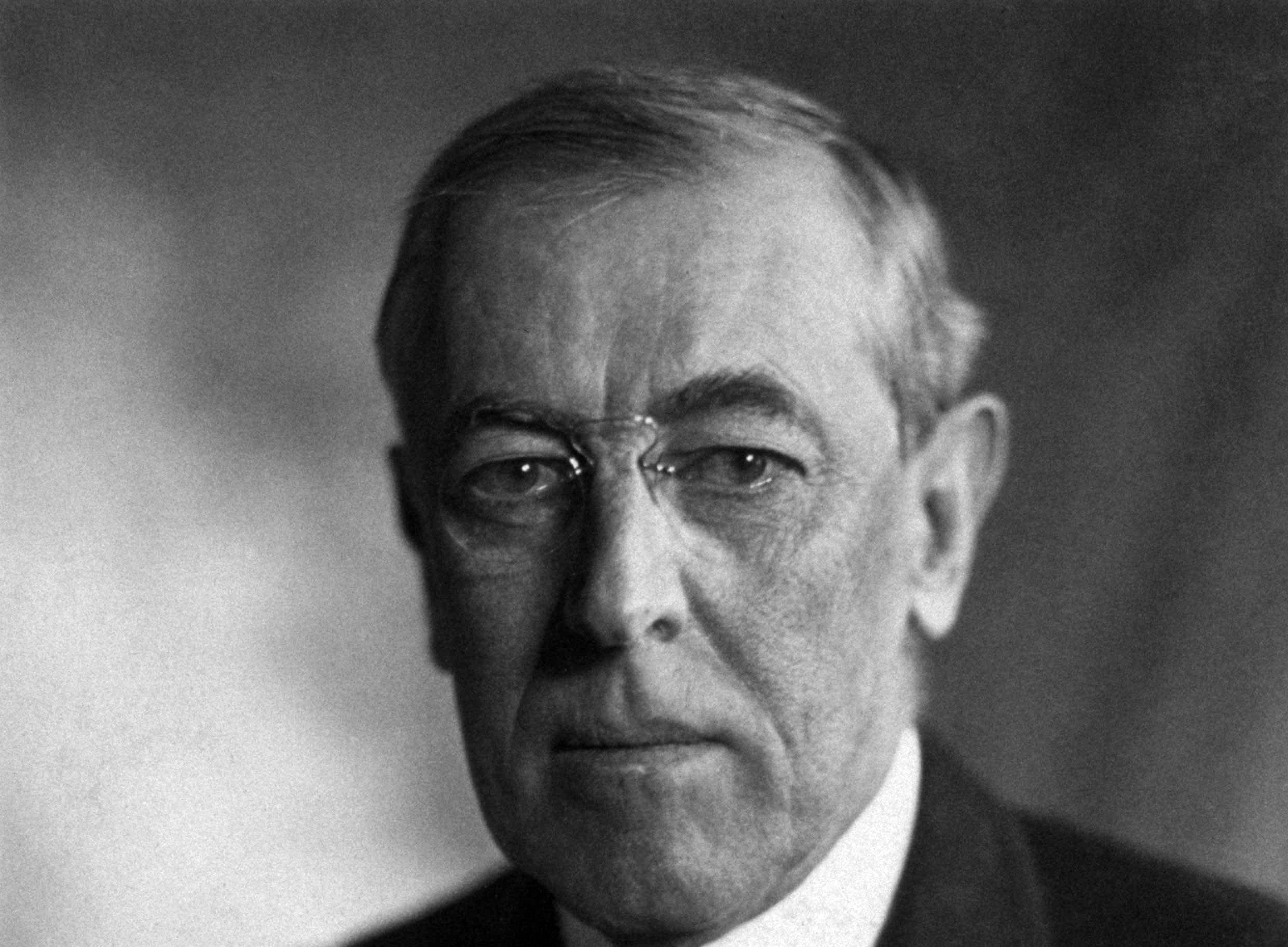

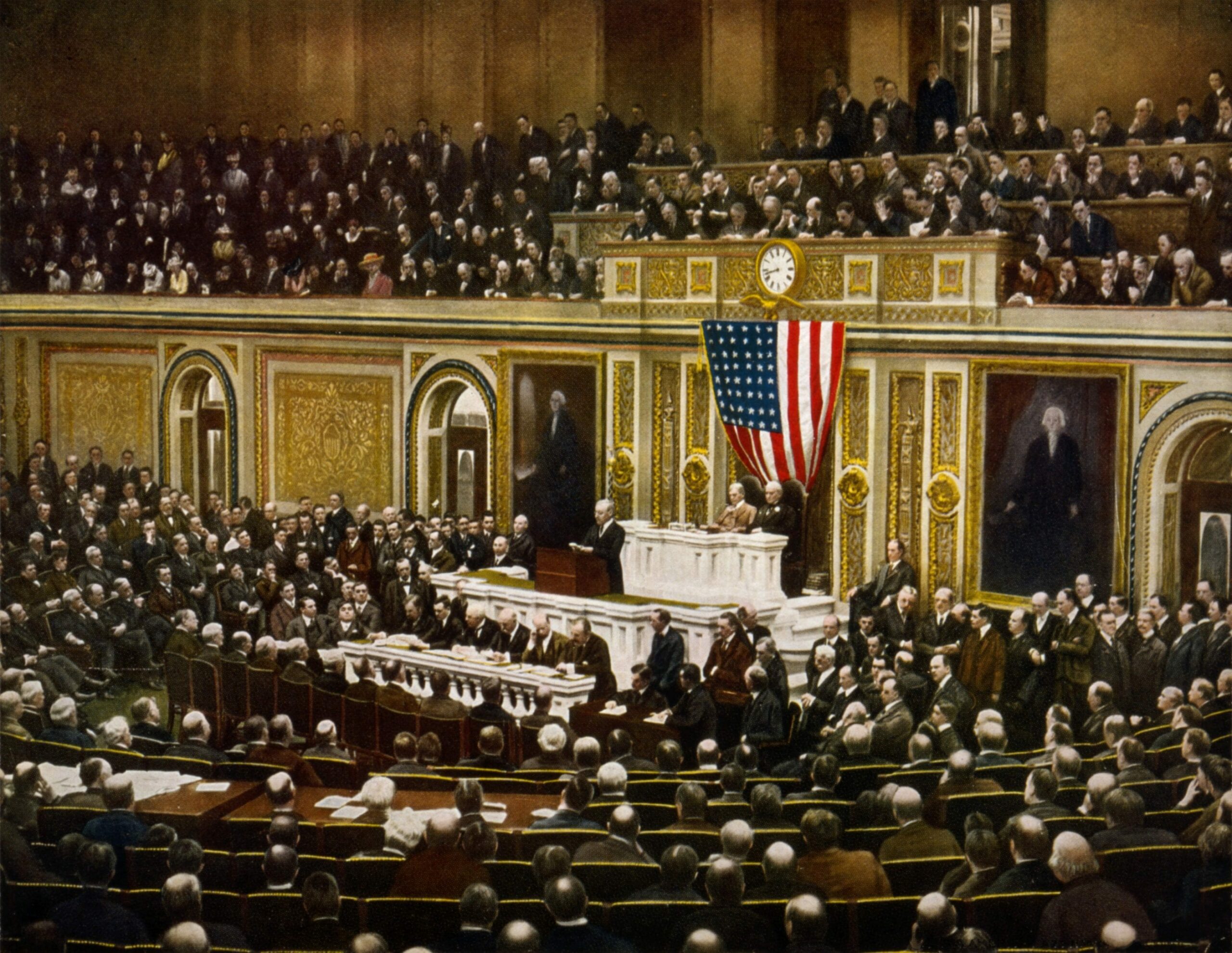

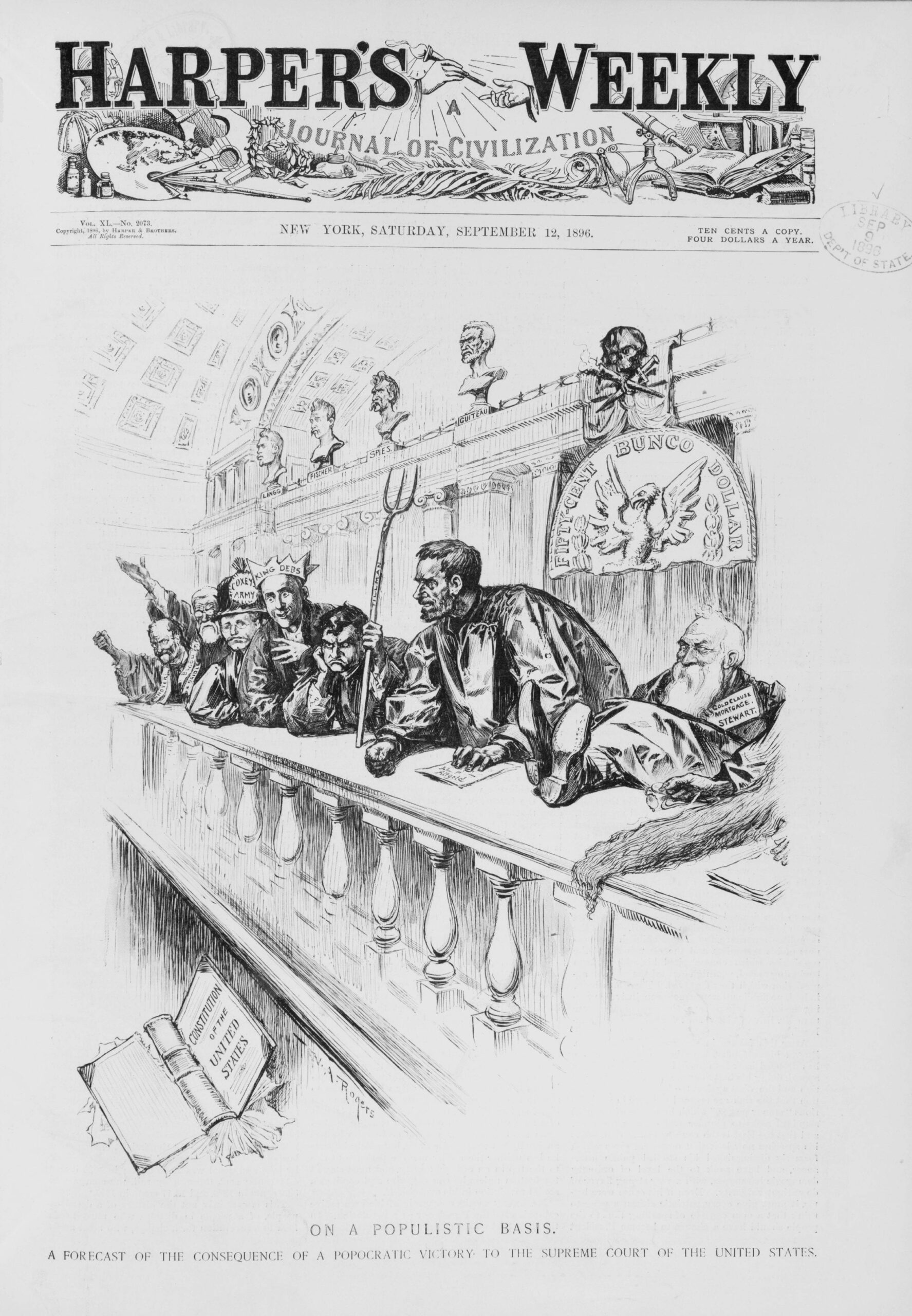

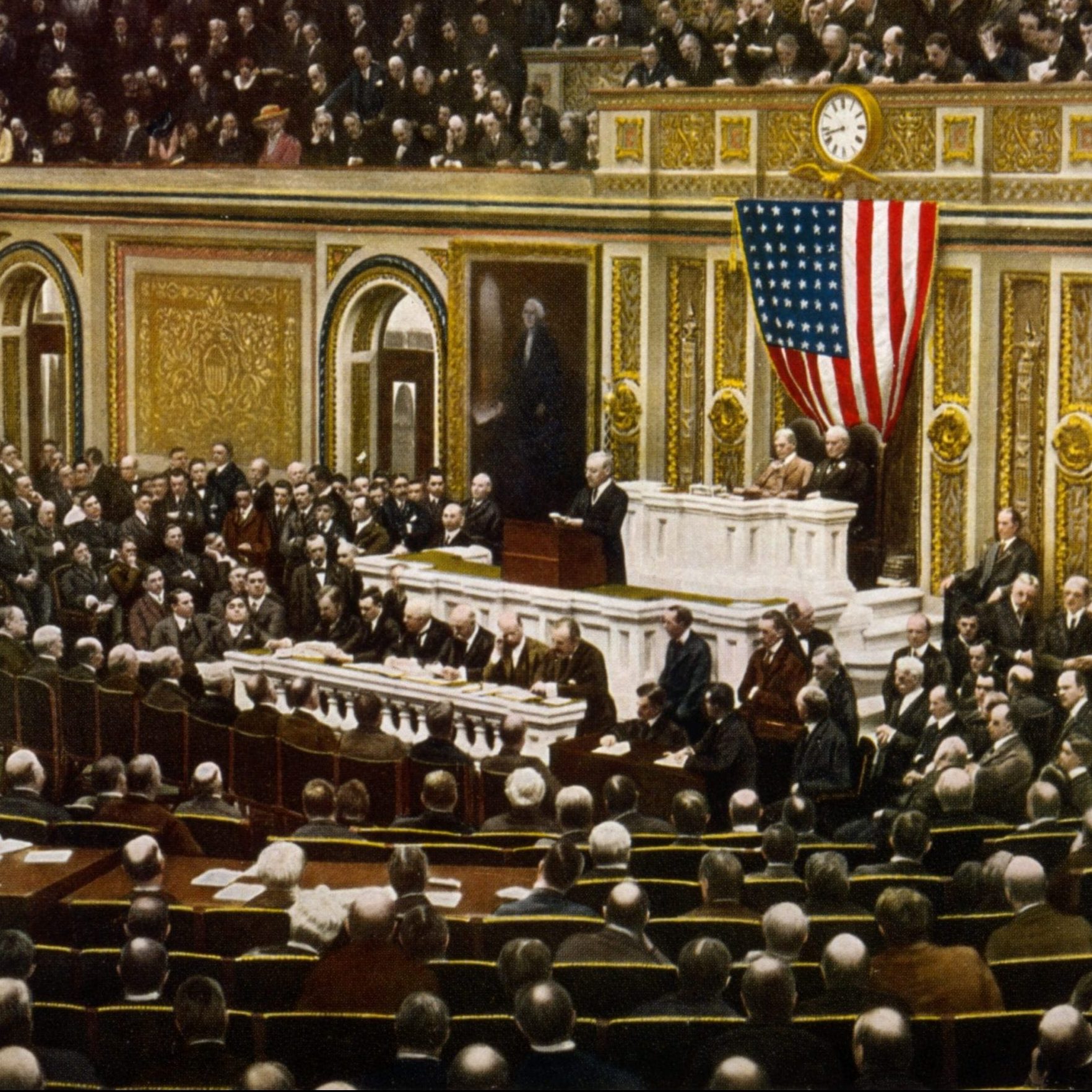

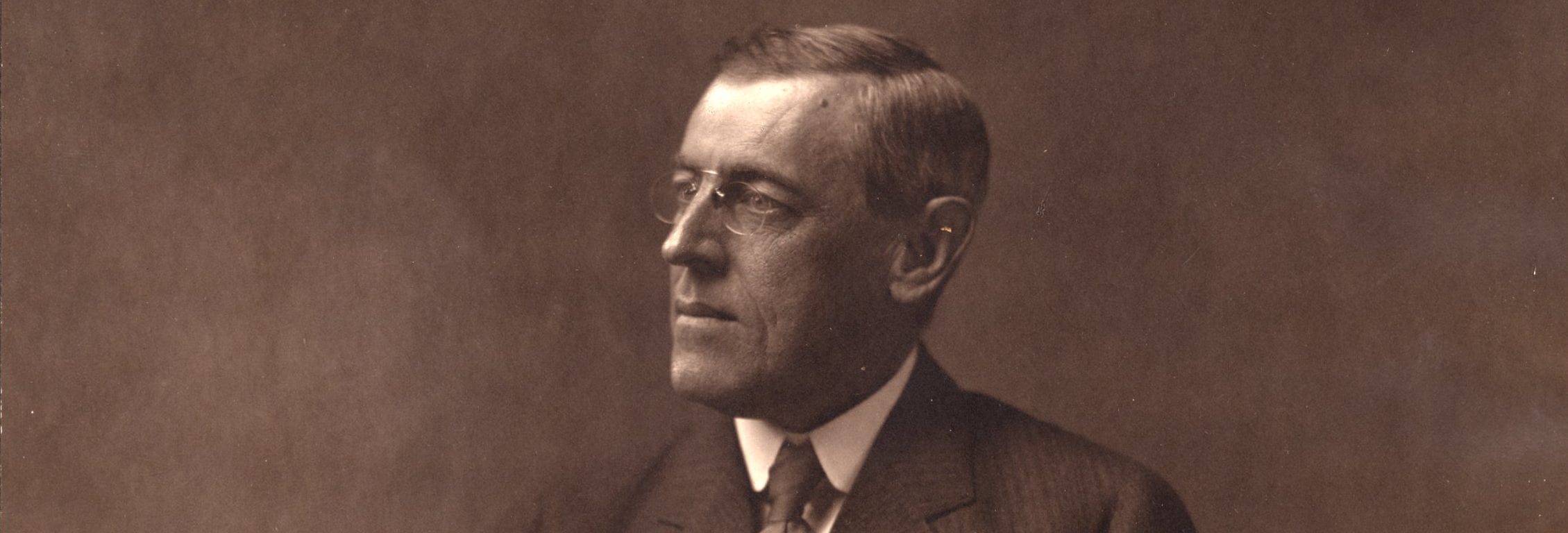

The young political scientist Woodrow Wilson wrote his first major book, Congressional Government, in 1885, describing what he saw as the greatest problems facing the nation’s legislative body. In this book, Wilson famously explained that “Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work,” and decried the fact that standing or permanent committees with a settled legislative jurisdiction (agricultural policy, foreign affairs, and so forth) held almost all of the power, especially in the House of Representatives. For Wilson, this was problematic because it made the decisions and deliberations of Congress less accessible and accountable to the people. Legislatures, in his view, should spend less time on the details of policy and more time debating broad ideas, so that the minds and hearts of the people are drawn into and engaged in the work of the government.

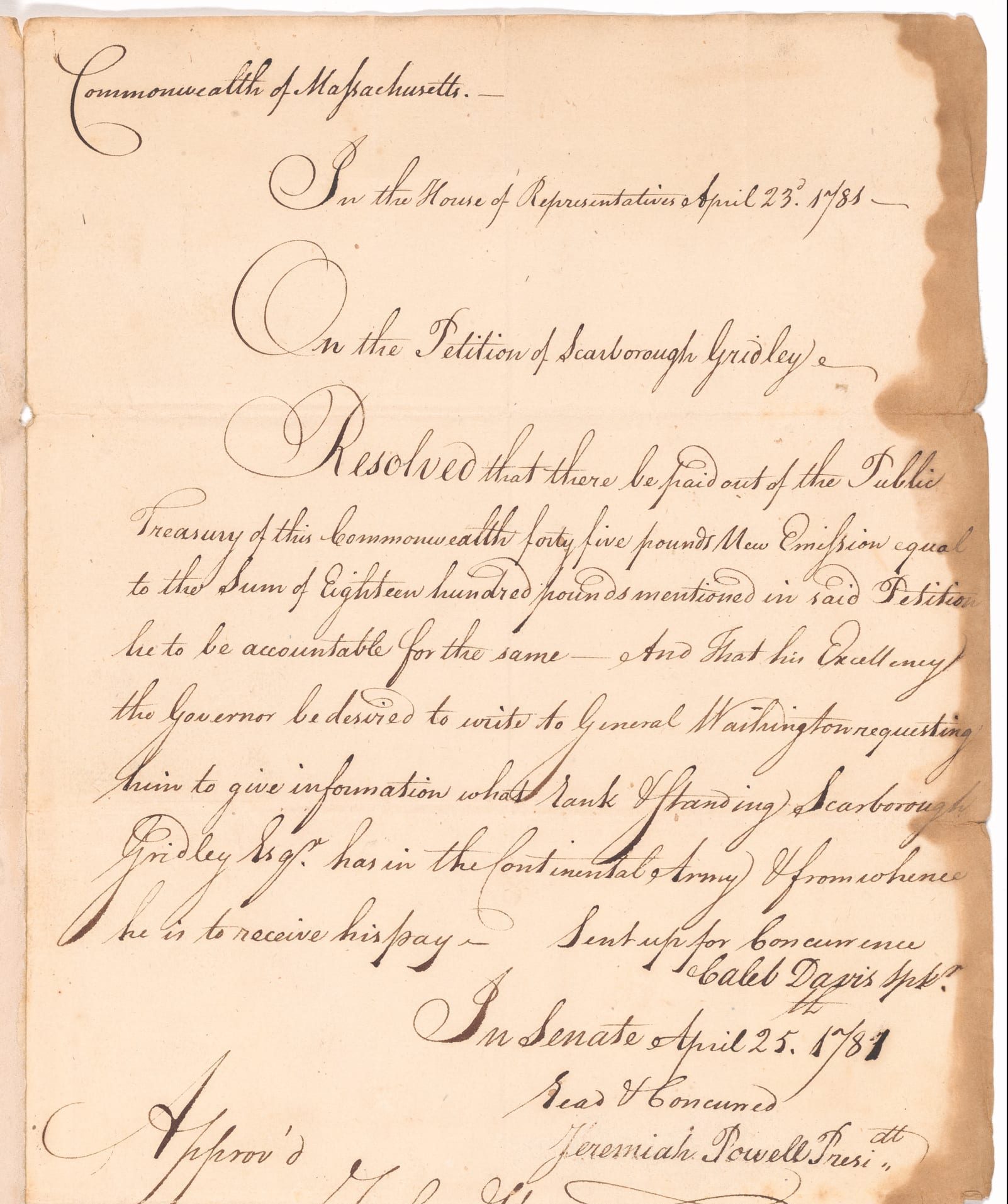

At the time he wrote Congressional Government, political parties were just beginning to gain the immense powers that party leaders would eventually use to control the proceedings of Congress (see “Rules of the House of Representatives” and “Obstructions in the National House” and “A Deliberative Body”). When he wrote his preface for a new edition of the book in 1900, Wilson noticed that parties had become much more powerful, almost making his analysis obsolete. The party leadership retained the old institutional structures, however, and the problem of committee governance remained. In 1900, he wrote, “The power of the Speaker has of late years taken on new phases. . . . To this new leadership, however, as to everything else connected with committee government, the taint of privacy attaches.” Thus, Wilson remained a critic of congressional government as it had evolved over the course of the nineteenth century. A better approach, he maintained, would be for Congress to act more like a debating society than a legislature, delegating its legislative powers to the executive branch and maintaining oversight of the administration to keep it accountable to the public (see also Constitutional Government in the United States).

Source: Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1885).

Like a vast picture thronged with figures of equal prominence and crowded with elaborate and obtrusive details, Congress is hard to see satisfactorily and appreciatively at a single view and from a single stand-point. Its complicated forms and diversified structure confuse the vision, and conceal the system which underlies its composition. It is too complex to be understood without an effort, without a careful and systematic process of analysis. Consequently, very few people do understand it, and its doors are practically shut against the comprehension of the public at large. . . . If Congress has a few authoritative leaders whose figures were very distinct and very conspicuous to the eye of the world, and who could represent and stand for the national legislature in the thoughts of that very numerous, and withal very respectable, class of persons who must think specifically and in concrete forms when they think at all, those persons who can make something out of men but very little out of intangible generalizations, it would be quite within the region of possibilities for the majority of the nation to follow the course of legislation without any very serious confusion of thought. . . .

But there is no great minister or ministry to represent the will and being of Congress in the common thought. The Speaker of the House of Representatives stands as near to leadership as any one; but his will does not run as a formative and imperative power in legislation much beyond the appointment of the committees who are to lead the House and do its work for it. . . .

The leaders of the House are the chairmen of the principal Standing Committees. Indeed, to be exactly accurate, the House has as many leaders as there are subjects of legislation; for there are as many Standing Committees as there are leading classes of legislation, . . . It is this multiplicity of leaders, this many-headed leadership, which makes the organization of the House too complex to afford uninformed people and unskilled observers any easy clue to its methods of rule. For the chairmen of the Standing Committees do not constitute a cooperative body like a ministry. They do not consult and concur in the adoption of homogeneous and mutually helpful measures; there is no thought of acting in concert. Each committee goes its own way at its own pace. It is impossible to discover any unity or method in the disconnected and therefore unsystematic, confused, and desultory action of the House, or any common purpose in the measures which its committees from time to time recommend. . . .

. . . The House virtually both deliberates and legislates in small sections. Time would fail it to discuss all the bills brought in, for they every session number thousands; . . . The work is parceled out, most of it to the forty-seven Standing Committees which constitute the regular organization of the House, some of it to select committees appointed for special and temporary purposes. . . .

. . . In form, the committees only digest the various matter introduced by individual members, and prepare it, with care, and after thorough investigation, for the final consideration and action of the House; but, in reality, they dictate the course to be taken, prescribing the decisions of the House not only, but measuring out, according to their own wills, its opportunities for debate and deliberation as well. The House sits, not for serious discussion, but to sanction the conclusions of its committees as rapidly as possible. It legislated in its committee-rooms; not by the determinations of majorities, but by the resolutions of specially-commissioned minorities; so that it is not far from the truth to say that Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee—rooms is Congress at work. . . .

One very noteworthy result of this system is to shift the theatre of debate upon legislation from the floor of Congress to the privacy of the committee-rooms. . . .

It would seem, therefore, that practically Congress, or at any rate the House of Representatives, delegates not only its legislation but also its deliberative functions to its Standing Committees. The little public debate that arises under the stringent and urgent rules of the House is formal rather than effective, and it is the discussions which take place in the committees that give form to legislation. . . .

There are, however, several very obvious reasons why the most thorough canvass of business by the committees, and the most exhaustive and discriminating discussion of all its details in their rooms, cannot take the place or fulfill the uses of amendment and debate by Congress in open session. In the first place, the proceedings of the Committees are private and their discussions unpublished. The chief, and unquestionably the most essential, object of all discussion of public business if the enlightenment of public opinion; a committee is commissioned, not to instruct the public, but to instruct and guide the House. . . .

For the instruction and elevation of public opinion, in regard to national affairs, there is needed something more than special pleas for special privileges. There is needed public discussion of a peculiar sort: a discussion by the sovereign legislative body itself, a discussion in which every feature of each mooted point of policy shall be distinctly brought out, and every argument of significance pushed to the farthest point of insistence, by recognized leaders in that body; and, above all, a discussion upon which something—something of interest or importance, some pressing question of administration or of law, the fate of a party or the success of a conspicuous politician—evidently depends. It is only a discussion of this sort that the public will heed; no other sort will impress it.

There could, therefore, be no more unwelcome revelation to one who has anything approaching a statesman-like appreciation of the essential conditions of intelligent self-government than just that which must inevitably be made to everyone who candidly examines our congressional system; namely, that, under that system, such discussion is impossible. . . .

. . . It is, therefore, a fact of the most serious consequence that by our system of congressional rule no such . . . means of controlling legislation is afforded. Outside of Congress the organization of the national parties is exceedingly well-defined and tangible; no one could wish it, and few could imagine it, more so; but within Congress it is obscure and intangible. Our parties marshal their adherents with the strictest possible discipline for the purpose of carrying elections, but their discipline is very slack and indefinite in dealing with legislation. At least there is within Congress no visible, and therefore no controllable party organization. . . . The only bond of cohesion is the caucus, which occasionally whips a party together for coöperativecooperative action against the time for casting its vote upon some critical question. There is always a majority and a minority, indeed, but the legislation of a session does not represent the policy of either; it is simply an aggregate of the bills recommended by committees composed of members from both side of the House, and it is known to be usually, not the work of the majority men upon the committees, but compromise conclusions bearing some shade or tinge of each of the variously-colored opinions and wishes of the committee-men of both parties. . . .

. . . It may be said, therefore, that very few of the measures which come before Congress are party measures. They are, at any rate, not brought in as party measures. They are endorsed by select bodies of members chosen with a view to constituting an impartial board of examination for the judicial and thorough consideration of each subject of legislation;. . . .

Congress always makes what haste it can to legislate. It is the prime object of its rules to expedite law-making. Its customs are fruits of its characteristic diligence in enactment. Be the matter small or great, frivolous or grave, which busy it, its aim it to have laws always a-making. Its temper is strenuously legislative. That it cannot regulate all the questions to which its attention is weekly invited is its misfortune, not its fault; is due to the human limitations of its faculties, not to any narrow circumscription of its desires . . . organic life. If legislation, therefore, were the only or the chief object for which it should live, it would not be possible to withhold admiration from those clever hurrying rules and those inexorable customs which seek to facilitate it. Nothing but a doubt as to whether or not Congress should confine itself to law-making can challenge with a question the utility of its organization as a facile statute-devising machine. . .

Legislation unquestionably generates legislation. Every statute may be said to have a long lineage of statutes behind it; . . . Every statute in its turn has a numerous progeny, and only time and opportunity can decide whether its offspring will bring it honor or shame. Once begin the dance of legislation, and you must struggle through its mazes as best you can to its breathless end,—if any end there be.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the enacting, revising, tinkering, repealing of laws should engross of such a body as Congress. It is, however, easy to see how it might be better employed; or, at least, how it might add others to this overshadowing function, to the infinite advantage of the government. Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration; and even more important than legislation is the instruction and guidance in political affairs which the people might receive from a body which kept all national concerns suffused in a broad daylight of discussion. There is no similar legislature in existence which is so shut up to the one business of law-making as is our Congress. . . .

An effective representative body, gifted with the power to rule, ought, it would seem, not only to speak the will of the nation, which Congress does, but also to leader lead it to its conclusions, to utter the voice of its opinions, and to serve as its eyes in superintending all matters of government,—which Congress does not do. The discussions which take place in Congress are aimed at random. . . .

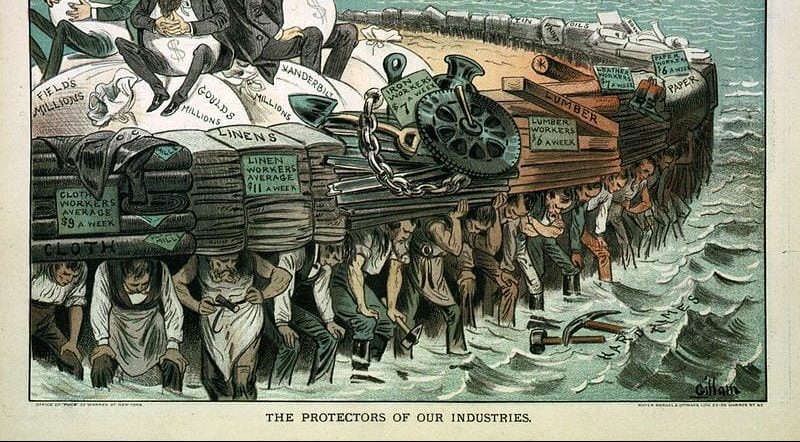

Congress is fast becoming the government body of the nation, and yet the only power which it possesses in perfection is the power which is but a part of government, the power of legislation. Legislation is but the oil of the government. It is that which lubricates its channels and speeds its wheels; that which lessens the friction and so eases the movement. Or perhaps I shall be admitted to have hit upon a closer and apter analogy if I say that legislation is like a foreman set over the forces of government. It issues the orders which others obey. It directs, it admonishes, but it does not do the actual heavy work of governing. . . . Members of Congress ought not to be censured too severely, however, when they fail to check evil courses on the part of the executive. They have been denied the means of doing so promptly and with effect. Whatever intention may have controlled the compromises of constitution—making in 1787, their result was to give us, not government by discussion, which is the only tolerable sort of government for a people which tries to do its own government, but only legislation by discussion, which is no more than a small part of government by discussion. What is quite as indispensable as the debate of problems of legislation is the debate of all matters of administration. . . .

It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and to talk much about what it sees. It is meant to be the eyes of the voice, and to embody the wisdom and will of its constituents. Unless Congress have and use every means of acquainting itself with the acts and the disposition of the administrative agents of the government, the country must be helpless to learn how it is being served; and unless Congress both scrutinize these things and sift them by every form of discussion, the country must remain in embarrassing, crippling ignorance of the very affairs which it is most important that it should understand and direct. The informing function of Congress should be preferred even to its legislative function. . . .

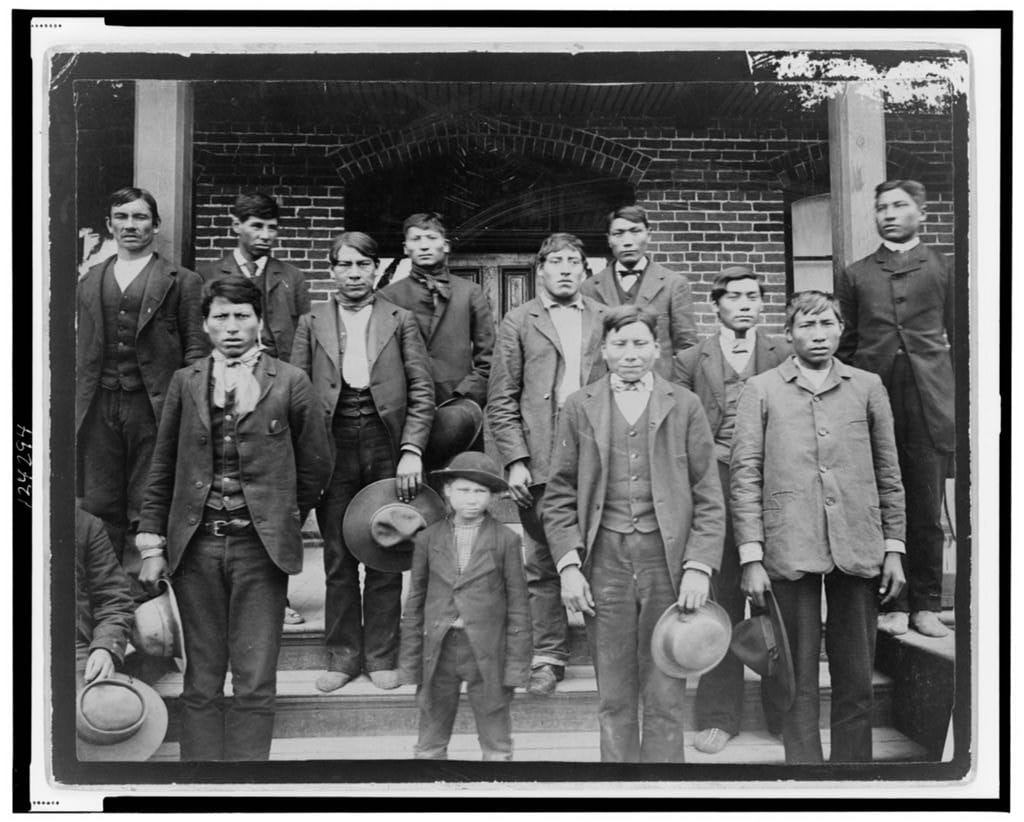

Statement of Geronimo

March 25, 1886

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.