American Foreign Policy to 1899: An Interview with Stephen F. Knott

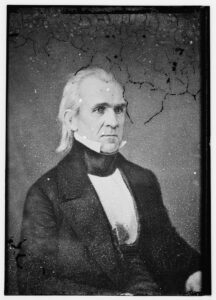

Teaching American History announces a new volume in its Core Document series, American Foreign Policy to 1899, edited by Stephen F. Knott. The volume covers the key events of its period, including the wars with Mexico and Spain, and such topics as the Monroe Doctrine and the debate over late nineteenth-century imperialism. It is distinguished by its attention to the role of the President in foreign policy and the use of clandestine operations by the United States.

Teaching American History announces a new volume in its Core Document series, American Foreign Policy to 1899, edited by Stephen F. Knott. The volume covers the key events of its period, including the wars with Mexico and Spain, and such topics as the Monroe Doctrine and the debate over late nineteenth-century imperialism. It is distinguished by its attention to the role of the President in foreign policy and the use of clandestine operations by the United States.

American Foreign Policy to 1899 forms a pair with the already published volume Westward Expansion. Together, these volumes show Americans struggling with the moral and political issues raised by our growing ability to extend power beyond our early borders. The new volume provides context for debates over covert action recounted in another core document volume, The Cold War, edited by David Krugler.

What makes this collection of documents different from other treatments of foreign policy in the nation’s first 125 years?

First of all, instead of restricting the focus to diplomatic correspondence, I included documents on secret operations in the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s rare to find even secondary sources on foreign policy prior to the 20th century that discuss what today we would call covert operations. I think these documents will come as a surprise to a lot of readers.

Because people think of covert operations as a modern innovation?

Exactly. Other than small military intelligence units for the Army and the Navy, a bureaucracy devoted to intelligence gathering did not exist prior to the creation of the Office of Strategic Intelligence (OSS) during the second world war and then the creation of the CIA in the National Security Act of 1947. But from the beginning, we used clandestine means to influence foreign governments to take a pro-American stance.

Was the older way of using clandestine operations more efficient?

It gave presidents flexibility, as well as an autonomy that could be both advantageous and dangerous. Presidents exercised great discretion over these operations. Congress had almost no role to play. One document I include is President’s Washington’s request for a “contingency fund” in his first annual message (January 8, 1790). Members of Congress who opposed his request called it a “secret service” fund. Washington asked that Congress appropriate money for this fund but not ask how he spend it—an extraordinary exception to Congress’s power to control the purse. Yet Congress gave Washington that authority.

This points to another theme of the collection: which institution of the federal government would be taking the lead when it came to determining, as well as implementing, American foreign policy? I sometimes laugh when people talk about the “imperial presidency” as a 20th century phenomenon. Right from the start, the presidency was given extraordinary powers over foreign policy, in particular over secret operations. Of course, I don’t see that happening were it not a request from George Washington. There was some serious resistance. Yet the collection shows the presidency emerging as the driving force behind foreign policy well before the world wars of the 20th century and the Cold War. The first document on this I include is Federalist 64. John Jay explicitly states that the president shall have control over “the business of intelligence.”

This seems a new issue in world politics—how a republic should organize its foreign policy. In giving control over this to the executive, did we resolve that question in the age-old way?

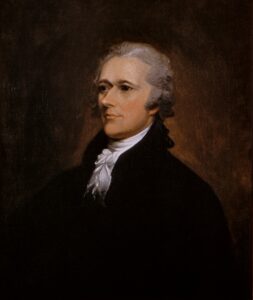

To some extent. Most of those who drafted the Constitution and implemented it under the administration of George Washington viewed executive power as most conducive to a coherent foreign policy. Washington and Hamilton, even Madison, had uncomfortable memories of our effort to conduct the Revolution by committee. After the endless delays, leaks of information, and changing policies coming out of the Confederation Congress, they were determined to give the new office of the presidency power to minimize those problems. As Hamilton said, the conduct of war in particular, and foreign policy in general, requires unity in the executive.

Still, as the Farewell Address shows, Washington did not want to overuse his authority. He advised restraint in foreign affairs.

At this point, the US is nowhere near acting as the world’s policeman. We are struggling just to get on our feet. Our presence around the globe is minimal. It’s a mistake to assume that at this point we were isolationists; we weren’t. But American Presidents and Congresses during this era wanted our intentions abroad to correlate with our capabilities. Like Washington’s Farewell Address, John Quincy Adams’ 1821 speech on the 45th anniversary of our independence emphasizes this restraint. Adams famously says the US does not “go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” At the time, some in Congress—Henry Clay, for example—wanted the US to intervene on behalf of a movement in Greece to overthrow the monarchy and install a republican government. President Monroe and Secretary of State Adams basically say, we wish you all luck, but we won’t intervene.

You open the collection with an excerpt from Jonathan Winthrop’s “Model of Christian Charity.” Do historians usually cite him in this context?

No! I’ve already taken some grief for it. Yet there is a difference between being a city on the hill, a model for others, and being the world’s policeman. Adams captures this perfectly. He’s certainly a believer in American exceptionalism, but not in exporting our beliefs at the point of a bayonet. Of course, he’s aware that the US has designs on territory in North America it doesn’t yet possess, perhaps the part of Mexico now known as Texas, but certainly Spanish Florida.

Acquiring Texas meant expanding slavery, which Adams opposed. Yet Adams saw Florida as a national security concern, because it was a sanctuary for runaway slaves and Native Americans who certainly did not see themselves as helping to build a new empire of liberty.

You do see in the early republic that when American statesmen opt for war, they make defensive arguments. That’s why President Polk goes to great lengths to provoke the Mexicans to fire the first shot in the Mexican American War. Lincoln saw this as an abuse of presidential power, leading to an immoral land grab.

What does the role of Congress become?

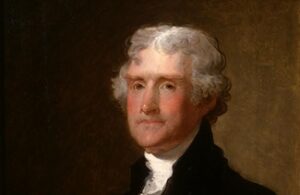

Two of the three declared wars during this period—the War of 1812 under Madison and the Spanish American War under McKinley—were in some ways actually driven by Congress. There was popular agitation for both. Some scholars say that Madison was dragged into the War of 1812 by Congress. Of course, William Randolph Hearst generated popular enthusiasm for intervention in Cuba and the Philippines. By contrast, President Polk manipulated Congress into declaring war on Mexico. With regard to conflicts with Native Americans, the quasi-war with France, or Jefferson’s attack on the Barbary pirates, Congress never declared war. They authorized funding and, at President John Adams’ request, agreed to increase the size of the US military. Yet the vast majority of 19th century hostilities were never Congressionally declared wars.

In part, this was due to the presidential control of information. For example, when Jefferson made war on the Barbary pirates, he did not give Congress a transparent accounting of events. He claimed he sent the Navy to the Mediterranean to respond to attacks on American shipping. In fact, he told the Navy to pursue the Barbary pirates in any way possible.

You argue our current disagreements over foreign policy stem from the disagreement between Jefferson and Hamilton during the first presidential administration. Some leaders take the realistic approach of Hamilton, others the idealistic approach of Jefferson. Weren’t both men’s visions in some ways unrealistic? Jefferson minimized security threats from Europe and hoped we could expand westward peacefully, through treaties and land purchases. Didn’t Hamilton minimize the importance of the Mississippi Valley to the nation’s security?

You’ve asked the rare question about Hamilton I find difficult to answer. On the one hand, Hamilton praised Jefferson for the Louisiana Purchase. He saw no need for Jefferson to apologize for acting without Congress’s approval. But it is true that Hamilton looked eastward. He wanted to build the conventional nation-state, with a professional army and navy and military academies. By becoming a great economic and military power, we could eclipse the great powers of Europe. Jefferson looked westward, sending Lewis and Clark on an expedition to bring him information of scientific and strategic importance. This shows him thinking about another real issue for the nation.

Jefferson saw a large standing military as a threat to liberty. He thought we could use the moat of the Atlantic to stay out of the perpetual wars of Europe while building a new order for the ages. Hamilton, I think, is less taken with the mission to be different from Europe. He’s more comfortable with conventional uses of force.

Hamilton does have some doubts about westward expansion; all the Federalists did. He did suggest, around the time of the quasi-war with France, creating an army to march into parts of Latin America. But I don’t see him, as some of his critics do, as a closet Caesar who would invade everywhere he could. He was devoted to strengthening the union and creating an economic and political foundation that would allow the US to take its rightful place in the community of nations.

Although Jefferson did not want to expend great sums on the military, he wanted to project American power, working toward an empire of liberty, and used secret operations to do that. He opted to bribe Native American chiefs to cede land, or (as Secretary of State) advocated providing weapons to one tribe to give it the upper hand over others. These are options short of war to save American blood and American treasure.

How does American foreign policy through 1899 differ in purpose and manner from American foreign policy today?

Actually, American foreign policy is beginning to change by 1899. A notion arises that the US should spread the gospel of liberty through military means. You see this in Theodore Roosevelt and in McKinley’s Secretary of State, Elihu Root. In the 1890s, the US emerged as the world’s number one economic power, realizing Hamilton’s vision of a century earlier. This emboldens some of those in progressive Republican circles to flex American muscles abroad while bringing our enlightened way of thinking to those in the rest of the world still wearing chains. That’s a radical departure from the Farewell address, the Monroe Doctrine, and Adams’ Fourth of July speech—even though Roosevelt calls his announcement that we may use force in Latin America a “corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. A prudential sense of America’s role in the world is replaced by an almost Messianic intent to bring the blessings of liberty to everyone.

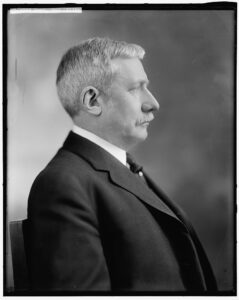

We can contrast this new thinking with Henry Clay’s “Market Speech,” delivered in the midst of the war with Mexico, and the last document in the entire collection, Carl Schurz’s speech “Against American Imperialism.” Both Clay and Schurz were dead set against annexation of foreign territory. Such action represented a betrayal of American founding principles, particularly the principle of government by consent. So, we see a minority dissent to America’s military actions to acquire Texas, Hawaii (in a completely underhanded presidentially directed operation during the Benjamin Harrison administration) and the Philippines during the Spanish American War. Schurz brings forward Lincoln’s perspective, believing many of his fellow Republicans have gone off the rails. What distinguishes Schurz and Clay’s speeches from 20th century critiques of America’s role in the world is that Clay and Schurz critique American imperialism while firmly believing in American exceptionalism.

During the 20th and 21st centuries, American presidents from Woodrow Wilson to John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush seem to think our exceptionalism obligates us to become imperialists. The failure of some of their projects has caused some Americans to disavow our exceptionalism. Some readers may wish we could recover the perspective of Clay, Lincoln and Schurz.

How would you advise readers to use your collection?

This conversation has made me realize how enormous this subject is. I hope readers will follow the threads that interest them, picking the book up to read a few selections, putting it down, and picking it up again later. After reading the general introductions, readers might go to the back of the volume to read through the Thematic Table of Contents, getting an idea of issues to explore. When reading particular documents, I suggest they refer to the study questions. These help explainwhy certain documents are included.

It’s the persistent themes that make this history interesting. For example, both Hamilton writing as Pacificus and Washington in his Farewell Address warn against forming emotional attachments to foreign governments. Yet some 20thcentury officials would make that mistake. Henry Wallace, FDR’s vice president, developed an unhealthy affinity for Russia, which he saw as a worker’s utopia. Some American conservatives prior to the second World War admired Hitler’s Germany because it was nationalist and anti-communist. American leftists in the 1960s developed romanticized views of Castro’s Cuba and North Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh. These aren’t just antiquarian documents; you do see parallels with the future.